Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Decoding Coercive Control: Advanced Strategies for Proficient Domestic Violence Assessment, presented by Sybil Cummin, MA, LPC, ACS.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Critique the difference between the incident model of domestic violence and the pattern-based model of coercive control and how this impacts victims and survivors.

- Apply the model of pattern-based coercive control to assessment practices when working with victims and survivors of domestic violence.

- Apply ethical decision-making skills when assessing and working with victims and survivors of domestic violence.

Risks and Limitations

Risks

- Mental health professionals should be aware of the legal and ethical boundaries associated with domestic violence (DV)/intimate partner violence (IPV) and must ensure that they are providing legally appropriate and ethical services.

- Domestic/intimate partner violence is a sensitive and potentially triggering topic. Participants, especially those who have experienced DV themselves, may find the content emotionally distressing.

Limitations

- Domestic/intimate partner violence is often characterized by complex power dynamics, manipulation, and control tactics. Understanding and navigating these dynamics can be challenging for mental health professionals, and supervision is encouraged and recommended.

- This training is not inclusive of the various cultural norms, values, and attitudes surrounding domestic violence. Therefore, practitioners are encouraged to seek additional training on cultural humility and intersectionality to be better able to honor each client’s diversity and unique challenges.

- This training provides generalized information regarding DV/IPV and does not provide state-specific information or client-specific information.

Introduction and Definitions

Let's begin with a fundamental definition of domestic violence or intimate partner violence. As the risks and limitations suggest, there's a variance in definition depending on the state of residence. In fact, each of the 50 states offers its own legal interpretation of domestic violence. Consequently, assessing and holding individuals accountable becomes considerably more challenging. Furthermore, different definitions may apply within advocacy or therapeutic contexts, complicating the overall picture.

Domestic violence, also known as intimate partner violence, is a systematic and willful pattern of power and control perpetrated by one intimate partner against another and includes, but is not limited to intimidation, physical assault, sexual assault, psychological and/or emotional abuse, and economic coercion. Three takeaways from this definition are that it's not solely physical violence, it is a systematic process, and it is willful.

Let's delve into the concept of coercive control. Renowned expert Evan Stark, highly regarded in this field, aptly characterizes victims of coercive control as "hostages at home." Coercive control manifests as a pattern of behavior that systematically strips the victim's liberty, freedom, and sense of self. In the context of working with survivors of domestic and intimate partner violence, it becomes evident that many lack a strong sense of identity. They grapple with profound self-doubt and find themselves unable to assert their own decisions for themselves and their families. The absence of freedom is palpable.

Another definition of coercive control is making a person subordinate or dependent by isolating them from sources of support, exploiting their resources and capacities for personal gain, depriving them of the means needed for independence, resistance, and escape, and regulating their everyday lives” (Stark, 2007; WHO, 2021).

When evaluating whether someone is a victim of intimate partner or domestic violence, it's crucial to scrutinize the areas where their autonomy is compromised. Victims often find themselves dependent on their partners, stripped of the ability to make decisions for themselves, and subject to stringent regulation of their daily lives by another individual. These hallmarks of coercive control serve as red flags, signaling the presence of abuse and the need for intervention and support. By recognizing and addressing these indicators, we can better identify and assist those trapped in abusive situations.

Domestic Violence Stats and Common Reactions

Some of the statistics surrounding intimate partner violence are truly alarming, and it's essential to bring them to light for those who may not be familiar with this issue. Consider this: 1 in 3 women and 1 in 4 men have experienced some form of physical violence at the hands of an intimate partner. This encompasses a spectrum of behaviors, ranging from slapping to shoving and pushing (WHO, 2021).

It's important to note that many instances of intimate partner violence may not fit traditional perceptions of domestic abuse. In fact, a staggering 58% of all cases involve coercive control—a crucial aspect to focus on. Understanding the presence of coercive control is pivotal for assessing the potential lethality of a situation and determining the feasibility of interventions like couples therapy.

Furthermore, the aftermath of leaving an abusive partner presents its own challenges. Up to 90% of women report experiencing continued harassment, stalking, or abuse post-separation (Hardesty et al. 2012, Mitchell et al. 2021). This is where my expertise lies. I specialize in supporting survivors navigating the complexities of post-separation abuse, particularly within the family court system. While some of my clients are still in abusive situations, many come seeking assistance after leaving their partners. This has been my focus for over five years, and I remain committed to providing tailored support to those in need.

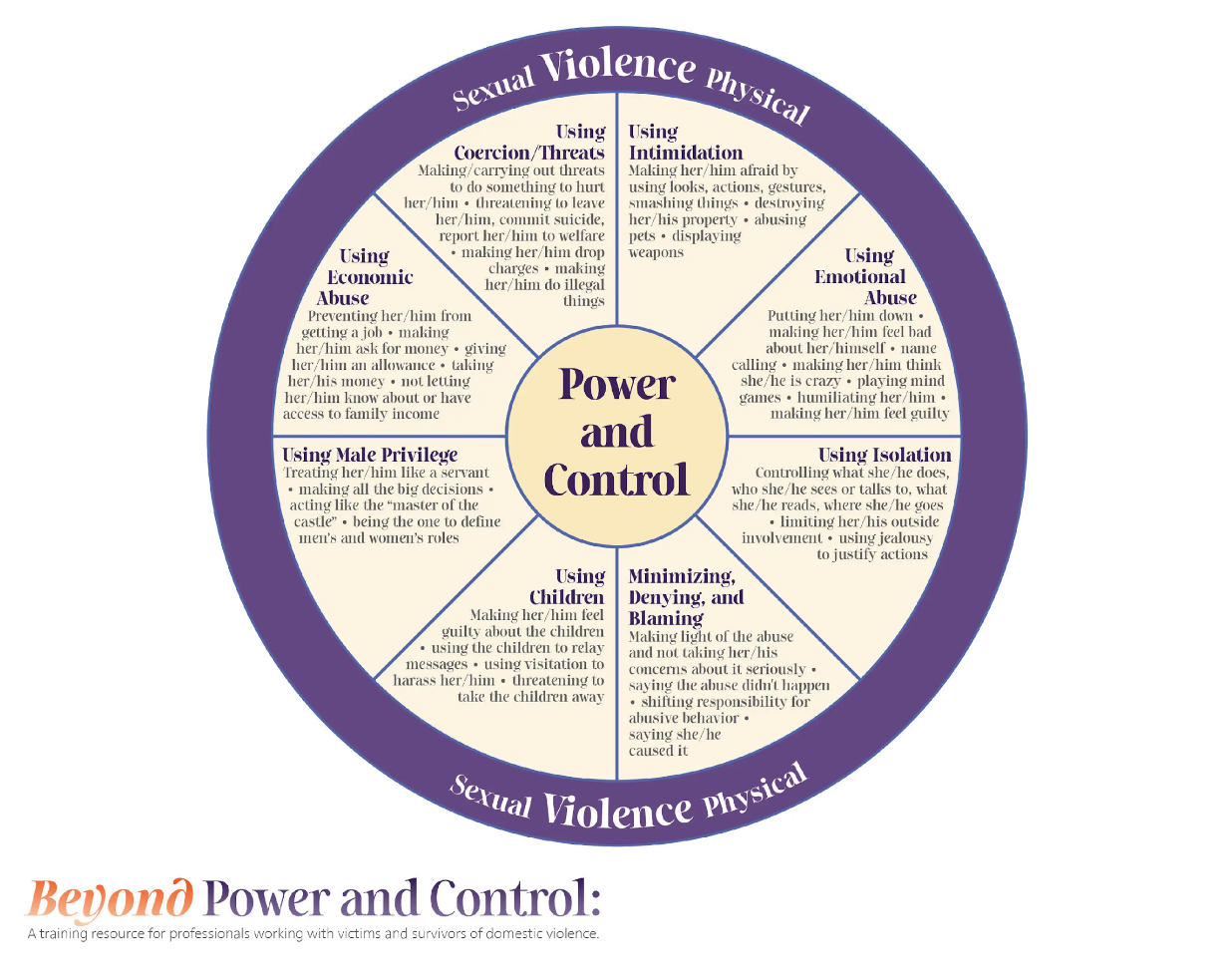

Figure 1 shows the Power and Control Wheel, which we won't cover extensively here, as you can find a detailed explanation in the resources section provided at the end. However, it's crucial to understand that physical and sexual violence within intimate relationships is often intertwined with various elements of coercive control. In essence, these forms of violence are underpinned by coercive control tactics. Without addressing these coercive control dynamics, it's challenging to fully grasp the dynamics of abuse in such relationships. Distinguishing between situational violence and domestic terrorism is important. Situational violence may involve isolated physical incidents, whereas domestic terrorism encompasses a broader spectrum of coercive control tactics, often without direct physical violence.

Figure 1. Power and control wheel. (Click here to enlarge this image.)

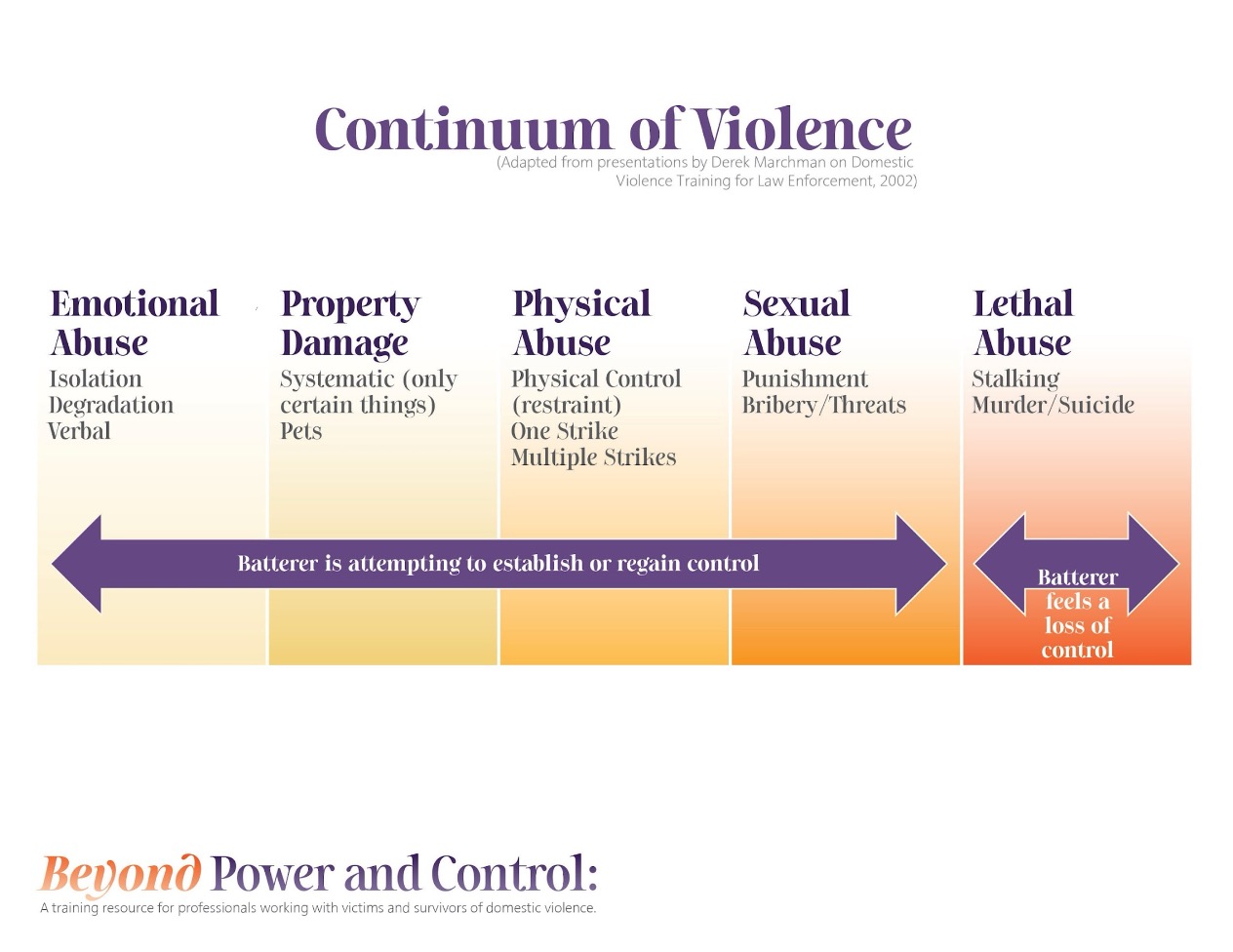

To illustrate some of the behaviors associated with coercive control, let's briefly touch on the continuum of violence, as seen in Figure 2. Perpetrators of abuse may escalate their tactics as they perceive a loss of control over their partner. This escalation can include increased physical, sexual, and even lethal forms of abuse. It's crucial to recognize that even in relationships without a history of physical violence, there's still a risk of lethality. Recent cases in the media highlight this unfortunate reality, where fatalities occurred despite no prior instances of physical abuse. As clinicians, it's imperative to adeptly assess for coercive control dynamics, as they serve as the primary indicator of potential escalation to lethal levels of abuse.

Figure 2. Continuum of violence. (Click here to enlarge this image.)

The Incident Model of Domestic Violence

Let's address the prevailing myth of the incident-based model in the context of how intimate partner violence is perceived and handled within our legal and judicial systems. Currently, many criminal courts, family courts, and child protection agencies operate under the premise of an incident-based model when addressing cases of domestic violence. However, this approach stands in stark contrast to our understanding of the complex dynamics inherent in intimate partner violence.

In criminal court proceedings, for instance, the focus tends to narrow solely on the specific incident of abuse that led to police involvement and subsequent arrest. The broader patterns of abuse leading up to that incident are often overlooked or deemed irrelevant. Similarly, in family court settings, if there's no formal conviction of domestic violence, judges may overlook available statutes designed to protect victims and survivors. This is symptomatic of the pervasive belief in the incident-based model, which oversimplifies the complexities of domestic violence dynamics.

Traditionally, the cycle of violence model has perpetuated this myth, emphasizing a cycle of tension, incident, and reconciliation. However, this framework fails to acknowledge the insidious nature of coercive control and its role in sustaining abusive relationships. In reality, the elements of coercive control—such as isolation, manipulation, and economic exploitation—are often more pervasive and damaging than individual incidents of physical violence.

The implications of adhering to an incident-based model extend beyond legal proceedings and into the realm of mental health treatment. Many survivors of intimate partner violence experience trauma that transcends singular incidents of abuse. The trauma is deeply intertwined with the erosion of autonomy and the systemic response to their experiences. Interactions with the legal system, including disbelief, reluctance to report, or fear of repercussions, often exacerbate this trauma, overshadowing the physical abuse itself.

In essence, the incident-based model fails to capture the full spectrum of abuse experienced by survivors of intimate partner violence. It is imperative that we shift towards a more comprehensive understanding of coercive control dynamics to better support survivors and address the systemic barriers they face in seeking justice and healing.

The Pattern-Based Model

To effect meaningful change in how we address intimate partner violence, it's imperative to shift from the entrenched incident-based model to a pattern-based approach. This paradigm shift is crucial across various professional spheres, whether you're a clinician, law enforcement officer, hospital staff member, or working in child protection. Rather than fixating solely on individual incidents, we must focus on identifying and understanding the patterns of coercive control that underpin abusive relationships.

Domestic violence doesn't suddenly materialize during a single incident—it often begins insidiously, sometimes even before the first date, particularly in the era of online dating. Elements of coercive control, such as manipulation and isolation, may manifest early in the relationship and escalate over time. By recognizing these non-physical forms of abuse as red flags, we can intervene before situations escalate to physical or sexual violence, potentially averting tragic outcomes such as homicide.

Indeed, the current rate of intimate partner homicides is alarmingly high. However, by shifting our collective focus to early intervention and prevention strategies rooted in understanding coercive control dynamics, we can reduce these devastating statistics. This shift requires a concerted effort to educate and raise awareness among professionals and the broader community about the insidious nature of intimate partner violence and the importance of identifying and addressing coercive control behaviors. By breaking free from the constraints of the incident-based model and embracing a pattern-based approach, we can work towards a future where fewer lives are lost to domestic violence.

Situational vs. Domestic Terrorism

When distinguishing between the incident-based and pattern-based models, particularly in contexts like couples therapy or child protection assessments, it's crucial to differentiate between situational abuse and domestic terrorism. Situational abuse typically stems from a deficit in conflict resolution skills or emotional intelligence, resulting in heated arguments or occasional physical altercations. While fear may be present, there's often a lack of pervasive patterns of control or autonomy deprivation within the relationship.

On the other hand, domestic terrorism, as conceptualized by Gottman and echoed in Sue Johnson's Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT), involves systematic patterns of power and control throughout the relationship. This encompasses various forms of abuse, including financial coercion, emotional manipulation, gaslighting, and minimizing behaviors. Notably, perpetrators may employ "love bombing" tactics early in the relationship, presenting a false facade to align with their partner's values before gradually revealing their controlling nature after commitments are made.

Importantly, domestic terrorism or intimate partner violence is not mutual or bidirectional. Instead, it's characterized by unilateral control exerted by one partner over the other, often involving coercive control tactics aimed at depriving the victim of autonomy and agency within the relationship. By recognizing these distinctions, professionals can better assess and intervene in cases of intimate partner violence, tailoring interventions to address the underlying dynamics at play.

Assessments

As a clinician, your role in working with clients affected by intimate partner violence may vary, influencing the assessments you choose to utilize. Formal assessments can offer valuable insights into the dynamics of coercive control and the level of danger faced by survivors. Here are some assessments commonly used in this context:

- Danger Assessment: Widely utilized by advocacy agencies, the Danger Assessment is adept at gauging levels of danger and assessing elements of coercive control. It is a 20-question assessment that provides valuable information for safety planning and intervention strategies.

- Lethality Assessment: Primarily utilized by law enforcement, the Lethality Assessment focuses on assessing the risk of lethality, particularly regarding the presence of weapons or instances of strangulation. It's a crucial tool consisting of four questions for determining immediate safety concerns.

- DALE Assessment: While less commonly known, the DALE Assessment boasts higher validity and reliability rates than the Lethality Assessment. It is an 11-question assessment also utilized by law enforcement to assess the likelihood of homicide. It specifically targets elements of coercive control. However, its cost may deter widespread use.

- Coercion in Intimate Partner Relationship Scale: This assessment stands out as the sole instrument currently available that comprehensively measures various tactics of coercion (Dutton et al., 2007), including economic, sexual, emotional, and psychological coercion. It offers a holistic understanding of the dynamics at play in abusive relationships.

Each of these assessments serves a unique purpose and can inform tailored intervention strategies. However, it's essential to recognize the challenges associated with using formal assessments, including cost, accessibility, and limitations in capturing the full spectrum of coercive control tactics. As such, a combination of formal assessments, clinical judgment, and ongoing evaluation is often necessary to effectively support survivors of intimate partner violence.

Limitations of Formal Assessments

Using formal assessments with clients affected by intimate partner violence comes with several limitations that must be acknowledged. Firstly, safety concerns may hinder survivors from answering truthfully, particularly if they fear repercussions from their abuser. This underscores the importance of creating a safe and supportive environment for disclosure.

Additionally, the language used in formal assessments may not resonate with survivors' understanding of their experiences. For instance, terms like "narcissistic abuse" may or may not align with survivors' perceptions of their relationships. It's crucial to use language that reflects survivors' realities and validates their experiences, even if it diverges from traditional terminology associated with domestic violence.

Furthermore, many formal assessments primarily focus on physical abuse and may not adequately capture the full spectrum of coercive control tactics, such as emotional or financial abuse. This limited scope can overlook the nuanced dynamics of abusive relationships and hinder accurate assessment and intervention.

Moreover, formal assessments are often normed based on specific demographics, such as cisgender male offenders and cisgender female victims, and may not account for diverse experiences or contexts. This can lead to misinterpretation of survivors' responses and overlooking their situations' complexities.

In response to these limitations, it's essential for professionals to approach assessments with cultural humility, sensitivity, and a trauma-informed lens. This includes actively listening to survivors, validating their experiences, and considering the broader context in which abuse occurs. Supplementing formal assessments with open-ended questions and qualitative inquiry can provide a more comprehensive understanding of survivors' needs and experiences. Ultimately, the goal is to empower survivors to share their stories in a safe and supportive environment, facilitating effective intervention and support.

Behaviors of Coercive Control

When assessing for behaviors of coercive control, professionals should consider a range of factors that may indicate the presence of abuse. While this list is not exhaustive, it highlights key behaviors that warrant attention.

- Isolation

- Excessive monitoring

- Denying autonomy

- Gaslighting and minimization

- Economic abuse

- Reinforcing traditional gender roles

- Using children

- Controlling access to medical care

- Making all sexual relationship decisions

- Threatening to harm pets/children

- Post-separation abuse

Isolation is a significant red flag. Professionals should assess the level of isolation experienced by the survivor, probing when it began and how it manifested. Isolation tactics may include limiting contact with friends and family, controlling communication, or monitoring movements.

Excessive monitoring is another concerning behavior to watch for. Signs of excessive monitoring may include constant check-ins, GPS tracking, or surveillance. It's important to explore how monitoring behaviors started and the methods used, including technological means.

Denying autonomy can erode a survivor's sense of agency. Professionals should evaluate whether the survivor has autonomy over personal decisions, such as clothing choices, religious preferences, or hairstyle. Denial of autonomy can manifest in various aspects of life and contribute to feelings of powerlessness.

Gaslighting and minimization are manipulative tactics commonly employed by abusers. Gaslighting involves manipulating the survivor's perception of reality, while minimization downplays the seriousness of abusive behaviors. The extent of gaslighting and minimization should be carefully examined.

Economic abuse is a pervasive form of control. Professionals should investigate the dynamics of economic abuse, which may involve financial control, exploitation, or sabotage. Economic abuse can take various forms, including restricting access to funds, ruining credit, or coercing financial decisions.

Reinforcing traditional gender roles can perpetuate power imbalances. It's important to identify instances where the abuser reinforces traditional gender roles without mutual agreement or through coercion. This may involve imposing rigid expectations related to gender roles and responsibilities.

Using children to further abuse is a particularly concerning behavior. Professionals should pay attention to whether children are used as tools to perpetuate abuse, both during the relationship and after separation. This can include using children to manipulate or control the survivor or engaging in parental alienation tactics.

Controlling access to care is another significant indicator of abuse. Professionals should assess whether the abuser controls the survivor's access to medical care, sexual health decisions, or threatens harm to pets and children. These behaviors can further entrench power imbalances and inhibit the survivor's ability to seek help.

Post-separation abuse can continue even after separation. Professionals should recognize that coercive control can persist, with abusers using various tactics to maintain control over the survivor's life. This includes harassment, stalking, legal manipulation, and undermining efforts to establish independence.

By carefully evaluating these behaviors and their impact on the survivor, professionals can gain a deeper understanding of the dynamics of coercive control and tailor interventions to promote safety and autonomy.

Assessing as a Clinician

As a clinician, assessing for coercive control and domestic violence may involve a nuanced approach that extends beyond formal assessments. Whether or not to use formal assessments depends on various factors, such as the specific goals of the assessment and the context of the client's situation.

Formal assessments may be useful if the goal is to determine the presence of abuse claims, especially in situations where caseworkers are involved. These assessments can provide valuable insights that inform safety planning and intervention strategies.

Additionally, formal assessments may be beneficial for determining the scope of practice or suitability for working with a particular client. For example, couples therapists may utilize assessments like those in Gottman's work to assess for the presence of domestic violence or terrorism within the relationship.

However, it's essential to consider the limitations of formal assessments, particularly in cases where safety or truthfulness may be compromised. Survivors living with their abusive partners may be hesitant to answer questions truthfully for safety reasons, potentially impacting the validity of the assessment results.

In such cases, clinicians can supplement formal assessments with targeted questions during intake or initial sessions. These questions can help gauge the level of autonomy and decision-making within the relationship, providing valuable insights into the dynamics of coercive control. Here are some examples of questions for your initial sessions.

- How are decisions made in your relationship?

- Does it seem like you have lost relationships with friends and family over the last X number of years?

- Has your physical health changed in the last X number of years?

- How has your confidence level changed over the last X number of years?

I often inquire about the decision-making dynamics within the relationship, prompting clients to provide examples. This helps me gauge the level of autonomy they possess in their relationship. Follow-up questions are essential for further elucidating this aspect.

Another question I frequently pose relates to changes in the client's relationships with friends and family over time. In cases of abuse and coercive control, the answer often reveals significant distancing from loved ones. Follow-up questions delve into the specifics of these changes, exploring factors such as geographical relocation, jealousy, lack of support, or conflicts with the partner.

Assessing changes in physical health is another important aspect of my evaluation. Victims and survivors of intimate partner violence commonly experience significant physical health challenges. I probe for any shifts in health status, such as the onset of autoimmune conditions or unexplained pain.

Additionally, I inquire about changes in the client's confidence levels over time. Many survivors experience a decline in self-assurance, which can be indicative of the psychological impact of coercive control. Exploring these changes provides valuable insights into the client's well-being.

These questions serve as valuable tools for assessing the presence of coercive control within relationships. While I no longer engage in couples therapy, I used to incorporate these inquiries into couple sessions as well. I approach these questions with sensitivity, particularly when suspecting the presence of domestic violence, to ensure the client feels safe and supported.

Why Are They Coming To See You?

As you assess clients, it's crucial to understand their primary reason for seeking therapy. Even if my expertise lies in working with survivors of domestic violence, narcissistic abuse, and coercive control, clients may arrive with different presenting problems. They might have been referred to me by another therapist due to symptoms like severe anxiety, unexplained weight loss, or identity struggles. Therefore, it's essential to explore the underlying reasons for their visit.

Individual Work

- Is the presenting problem IPV/DV?

- Would they resonate with the term “domestic violence”

- Where are they in the healing process?

For instance, severe anxiety might be linked to living in a coercive control environment, leading to trauma, dysregulation, and possibly depression. Assessing their relationships is paramount in understanding their mental health landscape.

Rather than immediately labeling them as victims of domestic violence, it's more effective to discuss specific behaviors they're experiencing and ask questions in a non-judgmental manner. By examining patterns over time, we gradually introduce psycho-education about their experiences. This approach fosters understanding without imposing labels prematurely.

However, prompt safety planning becomes imperative if the client faces imminent danger due to high lethality risks.

Another crucial aspect of assessment is gauging where clients are in their healing journey. Are they still in the relationship, feeling trapped in a trauma bond? Or have they managed to leave but remain dependent? Some may be ready to delve into trauma work, indicating progress in their healing process. Understanding their current stage aids in tailoring interventions to their specific needs.

Couples Work

- Are they safe enough to be honest?

- Assessing between situational violence and domestic terrorism?

When conducting couples therapy, it's crucial to determine if the clients feel safe enough to be honest with each other. Additionally, it's essential to differentiate between situational violence and domestic terrorism, which encompasses coercive control and intimate partner violence (IPV). If one or both partners are experiencing domestic terrorism, it's contraindicated to proceed with couples therapy.

Therefore, it's vital for therapists working with couples to feel confident and comfortable in assessing for signs of domestic terrorism. This ensures the safety and well-being of both partners and facilitates appropriate interventions tailored to their specific needs.

Child Therapy

- Is it ethical to continue working with them?

Clients seeking therapy for their child raise important considerations, particularly regarding the potential impact of domestic violence and coercive control on the child's well-being. While it may not be definitive, it's highly probable that children are affected by such dynamics in the home, even if the parents have separated due to post-separation abuse.

In instances where children are brought in for therapy, such as play therapy, it's imperative to conduct thorough assessments for signs of domestic violence and coercive control. Despite the focus on child therapy, these assessments remain essential.

Given the complexity of the situation, therapists must carefully evaluate the ethical implications of continuing therapy with the family. This involves considering whether it's appropriate to proceed with therapy and if the therapeutic environment is conducive to the child's well-being. The importance of ongoing assessment and ethical decision-making cannot be overstated when providing therapy for children impacted by domestic violence and coercive control.

Safety Planning and Continued Assessment

Once you've completed the assessment, the next steps are crucial. If the risk level is relatively low, meaning there hasn't been physical abuse, weapon use, or strangulation, and the pattern isn't escalating, your approach will differ. You'll focus on safety planning, particularly around high-risk behaviors and any threats that have been identified, including the rapid cycling of abusive incidents.

Safety planning around court decisions is paramount for survivors navigating the family court system post-separation. The period following separation, especially the first year, carries the highest risk of lethality. This is also a critical time to address child safety, as child homicides often occur when court decisions oppose the perpetrator's wishes. Continuous assessment and active listening remain essential, even if the survivor has left the abusive situation years ago.

In the provided resources, downloadable safety plans and videos are available. One is tailored for those still residing in the home, while the other is designed for individuals who have left. Additionally, there's a resource dedicated to tech safety, addressing concerns about potential monitoring through devices like cars and computers. Given recent instances of invasive monitoring tactics, such as key loggers where a partner can see every single keystroke made on the computer, it's crucial to remain vigilant and provide support and resources as needed.

Assessment Over Time

Assessment over time is crucial, especially considering that as your client improves, particularly if they're still in the same environment, the lethality risk may rise. This stems from the dynamics of coercive control, where the abusive individual escalates their behavior to maintain dominance when they sense losing control. Even if there hasn't been physical violence yet, it doesn't guarantee safety, even after leaving the situation. The normalization of coercive behaviors often hampers early assessment efforts. Clients may downplay, excuse, or even conceal aspects of their experiences as a survival mechanism rooted in a lack of trust in themselves and others.

This process can be gradual, and therapists may find themselves grappling with self-doubt and frustration over what seems like slow progress. It's important to acknowledge that these cases often progress at a different pace and require patience and persistence. Despite any challenges, therapists should recognize their efforts and the inherent difficulty of addressing abuse within the therapeutic setting.

Aha Moments

Your "aha" moments in therapy often stem from maintaining a non-judgmental stance and fostering a safe space for your clients. Prioritizing safety and trust-building lays the groundwork for accurate assessment and effective intervention. Unless there are immediate threats of violence or harm, your primary focus should be on creating an environment where clients feel secure and supported. This foundation of safety enables them to engage in the therapeutic process and absorb the psychoeducation and insights you provide.

When discussing coercive control and domestic violence, it's essential to begin with specific behaviors rather than labeling their experiences outright. By exploring these behaviors and identifying patterns, you empower clients to recognize the dynamics in their relationships. Additionally, it's crucial to respect their autonomy throughout the therapeutic journey. Avoid replicating the power dynamics of the abuser by allowing clients to make their own choices and decisions about their lives.

Your role as a clinician is to help clients reclaim their sense of self, rediscover their values, and regain autonomy over their lives. By fostering a collaborative and empowering therapeutic environment, you support clients in their healing journey for themselves and their families.

Examples

Example 1

Here's an example to illustrate the importance of understanding coercive control, even in cases where physical violence isn't present.

Kate, “But he never hit me.”

- Late 40s, one child, graduate degree

- Married 12 years

- Attended same church

- Moving her away from family, friends, job, church

- Slow shift in preventing her from making financial decisions

- Indirect emotional abuse

- Feigning concern for mental health

- Spiritual abuse

- Abuse ramped up after separation

A client sought therapy feeling completely off balance and anxious, yet she didn't perceive herself as a victim of domestic violence because her partner never physically harmed her. Despite this perception, her therapist referred her to me, noting my specialization in working with domestic violence survivors. In our sessions, she revealed a complex story: married for 12 years with a child, she seemed to have a stable life until she became pregnant, and subtle shifts began.

Initially, it seemed like a reasonable decision—moving for better opportunities and climate—but gradually, she was isolated from family, friends, her job, and church. Financial autonomy slipped away, and emotional abuse insidiously crept in, particularly targeting her family of origin. Her partner feigned concern for her mental health but weaponized it against her. There was also significant spiritual abuse.

After deciding to leave, the abuse escalated post-separation. Legal battles became relentless, draining her financially and emotionally. The constant court appearances hindered her job search, trapping her in a cycle of control and manipulation.

This case underscores the need to recognize coercive control beyond physical violence. Despite the absence of overt abuse, the client endured a systematic erosion of her autonomy and well-being. Her reluctance to seek help initially highlights the pervasive myths surrounding domestic violence, emphasizing the importance of understanding and addressing coercive control in therapeutic practice.

Example 2

Here's a case study involving a couple, AJ and Sandy, who initially sought therapy for communication issues and postpartum support. Despite eight months of therapy, Sandy's anxiety symptoms worsened. When the therapist inquired about physical violence at home, both denied any occurrence.

The narrative shifted from the couple's issues to escalating concern for Sandy's mental health, leading to a referral to a psychiatrist. The clinician reported starting to "feel something was not right" and sought consultation, prompting a discussion on restructuring sessions to focus on couple dynamics and probing into decision-making, finances, and care for the child. As the therapist held AJ accountable and asked probing questions, the sessions became tense, eventually culminating in a physical altercation that hospitalized Sandy.

Remarkably, throughout their relationship, there had been no prior incidents of physical violence. This case underscores the importance of ongoing assessment, as subtle signs of coercive control may not be immediately apparent. Recognizing these dynamics early on could have prompted a referral to individual therapy for Sandy before attempting couples work, as it became evident that the relationship dynamics posed significant risks.

Coercive control's insidious nature often keeps it concealed, making it challenging to detect. Our preconceptions about domestic violence and coercive control can blind us to its presence. The relationships affected by these dynamics may appear normal on the surface, further complicating identification. Moreover, victims themselves may struggle to recognize the extent of their situation.

Wrapping It Up

In conclusion, it's imperative to transition away from an incident-based approach to addressing domestic violence and coercive control. This shift is crucial because relying solely on isolated incidents overlooks a significant portion of abuse, limiting our ability to prevent further harm and protect vulnerable individuals, including children. Embracing a pattern-based model enables us to intervene more effectively and mitigate the risk of lethality, physical violence, and the psychological impact on children.

While formal assessments have their limitations, they remain valuable tools in our efforts to address coercive control. However, it's essential to recognize that assessing coercive control is a nuanced process that requires time and trust to navigate successfully. This is particularly true in couples therapy, where establishing rapport and understanding the dynamics of the relationship are paramount. Communicating this need for time and patience upfront can help clients appreciate the complexity of the assessment process and foster a collaborative approach to addressing their concerns.

Resources

NetDoctor. (2020). Coercive control. https://www.netdoctor.co.uk/healthy-living/a26582123/coercive-control/

Psych Central. (2023). Coercive control. https://psychcentral.com/health/coercive-control#humiliation

Stalking Awareness Organization. (n.d.). Definition FAQs. Accessed on 4/1/2024. Retrieved from: https://www.stalkingawareness.org/definition-faqs/#1537978411858-2c051fd6-222b

Beyond Power and Control. (2024). Physical Safety Checklist. https://www.beyondpowerandcontrol.com/uploads/8/3/2/8/83280480/bpac_physicalsafetychecklist.pdf

New South Wales Government. (2015). Domestic Violence Safety Assessment Tool (DVSAT). http://www.domesticviolence.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/file/0020/301178/DVSAT.pdf

Rising Beyond Power and Control. (2024). Resources. https://www.risingbeyondpc.com/resources.html

YouTube. (2023). [Is My Ex Tracking Me? Tips to Protect Yourself and Your Family]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ku07ZyBfDlU&t=2356s

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Fast Facts: Intimate Partner Violence. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/fastfact.html

References

Crossman, K. A., Hardesty, J. L., & Raffaelli, M. (2016). “He could scare me without laying a hand on me”: Mothers’ experiences of nonviolent coercive control during marriage and after separation. Violence Against Women, 22(4), 454–473. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801215604744

Dichter, M. E., Thomas, K. A., Crits-Christoph, P., Ogden, S. N., & Rhodes, K. V. (2018). Coercive control in intimate partner violence: Relationship with women's experience of violence, use of violence, and danger. Psychology of Violence, 8(5), 596-604. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000158

Johnson, M. P. (2008). A typology of domestic violence: Intimate terrorism, violent resistance, and situational couple violence. Northeastern University Press.

Jones, M. S. (2020). Exploring coercive control, PTSD, and the use of physical violence in the pre-prison heterosexual relationships of incarcerated women. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 47(10), 1299-1318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854820920661

Kennedy, A. C., Bybee, D., Mccauley, H. L., & Prock, K. A. (2018). Young women’s intimate partner violence victimization patterns across multiple relationships. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 42(4), 430–444. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684318795880

Lohmann, S., Cowlishaw, S., Ney, L., O’Donnell, M., & Felmingham, K. (2024). The trauma and mental health impacts of coercive control: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 25(1), 630-647.

Spearman, K. J., Hardesty, J. L., & Campbell, J. (2022). Post-separation abuse: A concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 00, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15310

Stark. (2007). Interpersonal violence. Coercive control: How men entrap women in personal life. In Interpersonal violence. Coercive control: How men entrap women in personal life (Editor). Oxford University Press.

Stark, E., & Hester, M. (2019). Coercive control: Update and review. Violence Against Women, 25(1), 81–104.

Yaxley, R., Norris, K., & Haines, J. (2017). Psychological assessment of intimate partner violence. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 25(2), 237-256. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2017.1356211

Additional Current References

Please Note: The following resources have been included so members can view additional resources associated with this topic area. The presenter did not use these resources when creating this course.

Becker, P., Miller, S. L., & Iovanni, L. (2024). Pathways to resistance: Theorizing trauma and women’s use of force in intimate relationships. Violence Against Women, 1. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778012241233000

Cardenas, I., Graham, L. M., Sarmiento Mellinger, M., & Ting, L. (2024). Individuals who experience intimate partner violence and their engagement with the legal system: Critical considerations for agency and power. Journal of Health Care Law & Policy, 27(1), 113–144.

Juarros-Basterretxea, J., Fernández-Álvarez, N., Torres-Vallejos, J., & Herrero, J. (2024). Perceived reportability of intimate partner violence against women to the police and help-seeking: A national survey. Psychosocial Intervention, 33(1), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2024a3

Lohmann, S., Cowlishaw, S., Ney, L., O’Donnell, M., & Felmingham, K. (2024). The trauma and mental health impacts of coercive control: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 25(1), 630–647. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380231162972

Peeren, S., McLindon, E., & Tarzia, L. (2024). “Counteract the gaslighting” – a thematic analysis of open-ended responses about what women survivors of intimate partner sexual violence need from service providers. BMC Women’s Health, 24(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-024-02943-1

Cummin, S. (2024). Decoding coercive control: Advanced strategies for proficient domestic violence assessment. continued.com - Counseling, Article 55. Available at www.continued.com/counseling