Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, When to Worry About a Child’s Worries, presented by Andrea Roth, PsyD, LP.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Explain when worry transitions from normative to clinical/concerning

- Identify different types of pediatric anxiety

- Describe the framework of treating anxiety in the pediatric population

Introduction

I am excited to get started. Today's topic of conversation is when to worry about a child's worries. We will discuss when to draw the line between typical and clinical worries. Due to today's timing, this will not be a deep dive into the training model, but it will be an initial glance at a framework for treating anxiety in children.

Limitations/Risks

As I mentioned, the limitations and risks for the presentation and learning today are to provide an initial and broad overview of anxiety in the pediatric population. It is not meant to be used as the basis for an official diagnosis, nor should it be used to create a comprehensive treatment plan. The presentation today should not substitute for clinical consultation and supervision. It should not be used to replace a full diagnostic interview. It is attended for an initial first glance and then the risks. A common potential risk could be a potential misdiagnosis of a pediatric anxiety disorder. Let's get into it.

Anxiety: Normal or Not?

Anxiety is the big question today, and my first slide is the biggest one. Is it normal or not? Yes, overwhelmingly yes, anxiety is not just normal. It is expected, it is typical, and it is great. When I work with children, particularly teenagers, the first thing I say to them is that if we did not have anxiety, we would not look both ways before crossing the street. Anxiety makes us look both ways and not just run into traffic. It is the thing that gets us up in the morning and gets us moving and to school or to work. These are all things that anxiety gifts us. It is not just normal. It is great. It is an adaptive system in the body that tells us when we are in danger. Like adults, we experience anxiety probably several times a day, do kids and teens, they may get anxious or express anxiety if they are afraid of the dark, they are maybe starting at a new school, they are taking a test, they might be worried about seemingly smaller things like getting a pimple, but it becomes problematic when our body tells us that there is a danger when there is no real danger, the discomfort, and anxiety that I listed in all those situations, it is considered normal and even beneficial. It can be motivating and productive. An example of that again would be if I had a job interview or a child had a test. Anxiety might be what makes us prepare.

If we talk about that difference, it is problematic when there is no real danger. The analogy that I take to a lot of kids is what we say, I think a lot of us say this, long ago, there were cavemen, and there were actual animals that were out in the wild, and they were coming up to you. Or there was a bear, potentially an actual bear that would attack you. Today that does not happen, but way back then, they needed that. They needed that "fight or flight" response to keep them safe. Over time that has evolved, and that same response we get when there was an actual bear in the cave with us still happens when we are about to take a test or go into the interview. We often will say to kids that there is no bear in the room. Our body thinks that there is a bear in the room. Again, that is when we can draw the line when we are having these large responses, when there is no bear in the room, and when there is no real danger.

Developmentally Appropriate Fears

- Early childhood – separation anxiety, unfamiliar situations, dogs, spiders, monsters/ghosts

- Elementary school – real world dangers (fire, storms, intruders, illness, drugs)

- Middle School – social status and social acceptance, academic and athletic performance

- High school – social issues, future success, moral issues (Evans, et al., 1999)

Let's dig into those developmentally appropriate, potentially even helpful, age-appropriate fears. I broke it down into different ages and stages. I think this is important because any of us who went to graduate school may learn about developmental ages and stages, the typical fears and development that occurs at each stage. I think particularly for parents who did not take these courses do not know these things. At times, they have a lot of questions, i.e., is it normal that Johnny worries about this? Or gosh, Johnny's worried about this, and I do not think they should be. I will outline at which age and stage fear is developmentally typical.

Early childhood is typically preschool, the five years of age or under crowd. The one we all know and think about is separation anxiety. It is not uncommon. It is not concerning if a kid hesitates to separate from their parent. If they do not like going into an unfamiliar situation or a brand-new place. Separating from the adult they are familiar with is a very age-typical fear. Then we move into the other scary stuff. You might know some adults who are afraid of these things, like dogs and spiders or creepy crawlies. Little kids are afraid of those, and because of the developmental age of a five-year-old and under, they have magical thinking. At that age, they still think that monsters and ghosts could be real. They are not old enough and intellectually advanced enough to understand that these are things in stories and movies and are not real, making it a pretty true fear for them.

If we shift down to elementary school, this is a kindergarten through five years of age, depending on where you live and your school district. These are more real-world dangers, fires, storms, intruders or burglars, illness, and drugs. The reason why I think this is relevant at this age is that kids at this age are starting to hear more. They are aware of more. There are fire, storm, and tornado drills in school. Kids these days have intruder drills in school. They might have friends with older siblings. They might be exposed to the news or other conversations they hear. They are exposed to much more at this age, but developmentally and intellectually, they are possibly and probably not advanced or old enough to pull these things apart. We have these fire drills four times a year in school, which must make it a real threat. However, they do not necessarily have the ability to sit down and think, "Okay, but actually, how often have there been fires in school?" Again, they are exposed to much, but they do not have the intellectual awareness to pull apart and understand the nuances of these factors.

Shifting into middle school, I think social status becomes something they often think about. Social acceptance and their academic and athletic performance. They are just more aware of comparisons between each other. Grades are more of a factor. They are more present, aware, and potentially ranked and rated. They are coming in first place and second place in their athletic events. They are aware and a little more fearful and anxious around these things because they are typical. If it is not clinically concerning, it might be the thing that motivates them. It might be the thing that makes them run faster or helps them practice more.

In high school, they get into more anxiety around social issues, future success, and moral issues. Adulthood is right around the corner, and they are starting to think and then eventually maybe worry a little bit about what is next. What does that mean for me, moving out? When we look at moral issues, I draw the comparison back to that elementary school. These kids are thinking about potentially some of the same things. Still, they have that more advanced, more developed intellectual ability to piece apart or pull apart these more complex moral issues they are exposed to. Those elementary kids hear similar stuff, but they do not understand it. High school kids hear that stuff, but they, for the most part, can understand it a little bit better. These are the developmentally appropriate fears. Now we are going to shift to the big question, when do we worry about it? The difference between normative typical anxiety and worry from an anxiety disorder is the severity of the anxiety.

When To Worry About Anxiety

- Anxiety becomes a problem when it interferes with functioning

- Intensity

- What is the degree of the stress present?

- Impairment

- Does the stress interfere with daily life?

- Flexibility

- Can your child recover when the stressor is not present?

While feeling anxious is a very natural reaction to stressful situations. It becomes a disorder and clinically concerning when it interferes with a child's ability to handle everyday situations and prompts them to avoid things that most people their age typically enjoy. It interferes with their functioning. We look at these three aspects, intensity, impairment, and flexibility. What is the intensity? What is the degree of stress that they have? Are they a little bit nervous that they can move forward, or is it very consuming? Are they having very big somatic symptoms? Is it very intense for them?

Impairment, I think, is very important to look at. Does it interfere with their daily lives? As adults, our job is very obvious. Is it the job you are sitting in your office doing, it is in the home, it is out of the home, or do you have a job? It is a part of your family member. Maybe it is being a spouse or being a parent? When we talk about their job in childhood, kids love when I ask, what is your job? Their jobs are primarily going to school, being a friend, being a daughter or son, and potentially some extracurricular activities.

Are their fear and anxiety interfering with one of those functions? A pretty good example I like to point out when we talk about impairment is a five or six-year-old with some anxiety around perfectionism. It will start interfering with their job at school because this child may be reluctant to try something new that they have learned. They are reluctant to read because they shut down. They fear getting it wrong, saying it wrong, and not being able to do it perfectly, So they will shut down rather than keep trying repeatedly. Maybe they are reluctant in their extracurriculars, the soccer team they are on. They are scared and refuse to play in the game or play in practice. They are not practicing or doing everything with everyone else because either that one time they did mess up or maybe did not even mess up, but they have this internalized fear of not doing it well enough. Not being as good as the other kids. If we look at impairment, we want to consider their daily lives. How much is this getting in the way?

Lastly, flexibility, can they recover? Are they resilient? Again, because fear is typical and daily, many times a day, can they recover from it? Going back to the earlier example, the kid on the soccer field kicks and misses, and a moment of shock is expected. They might fear what happens if I do that again, but can they flexibly get past it? Can they either take a break and come back? Can they keep playing in the game, or is it just a total shutdown if they mess up? Are they just done? Are they done for the day? Can they come back from it? Can they flexibly recover from these sorts of stressors is a big thing to look at.

- Severe anxiety is unrealistic

- Severe anxiety is out of proportion

- Severe anxiety is being overly self-conscious

- Severe anxiety is often unwanted and uncontrollable

- Severe anxiety doesn’t go away

- Severe anxiety leads to avoidance

These are really important bullet points. I am going to read each one, and I am going to give an example of each because I think it is important to dig into these. Severe anxiety is unrealistic. The example I like to give is a kiddo with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). They might worry if they have contamination-based OCD, AIDS or HIV, or some other severe illness from touching a doorknob or touching other people's things. Or they are worried that they might become sick and seriously ill if they see words written with red ink or something specific. To us, that sounds completely unrealistic, but for a child with OCD, it feels very real to them. From the outside, it is a very unrealistic association, a very unrealistic worry, and out of proportion.

The example here is the high school student, the sophomore maybe, who stresses overtaking the SATs. It is just that a sophomore taking the SAT is absurdly stressed over it to the point where it affects all parts of them. They are having somatic symptoms, and they are not sleeping. They are stressed out over it. Maybe another child with a generalized anxiety disorder might have trouble sleeping because they have worries about a spelling quiz the next day. It is typical for a junior to be a little anxious before their real SATs, but for those younger kids who are stressed out, unable to sleep the whole night, and not eating in anticipation of a test, I think we can examine that part.

Severe anxiety is being overly self-conscious. An example here is of maybe a boy feeling a little nervous about talking to the girls in his class. Someone with a social anxiety disorder might avoid ordering in a restaurant because they are afraid of humiliating themselves. They do not order. This is not a three-year-old. This is an older child who will not order or will not speak to someone in public because they are very worried about humiliating themselves. Severe anxiety is often sadly unwanted and uncontrollable.

An example is a kindergartner who might cry at school because they miss their mom, or maybe a little boy with separation anxiety might cry at school because they cannot stop thinking about his mom dying if he is away from her. These are not thoughts that this child wants to have. They are unwanted and uncontrollable, but they keep coming back up. Kids will vocalize this, "I do not want to think about this. It just keeps coming into my head. I cannot stop it." Severe anxiety does not go away. It is not a phase or a stage. Sadly, it does not disappear as time goes on.

Another example would be anxiety is common and even expected after a disturbing experience, but over time most resilient children will bounce back from them. Three months later, a girl with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) will still have nightmares, leading to avoidance. Another kiddo who might be nervous about attending a birthday party avoids it because of social anxiety. They are very worried about maybe humiliating themselves. They want to go to the birthday party and see all their friends, but they cannot do it, and they avoid it because of the anxiety they are experiencing. Maybe another kiddo with a specific phobia, fearful of loud noises, might refuse to go to a birthday party or a concert with the family or the park because they are afraid it could be loud. Maybe a balloon would pop at the birthday party. They are avoiding things that other kids their age might typically enjoy and things that they want to do but avoid because of the anticipated anxiety that they might have.

Red Flags

- Stomachaches or headaches without medical cause

- Difficulty falling asleep due to excessive worry

- Recurrent nightmares • Persistent school refusal/problems

- Inability to concentrate

- Reluctance to socialize or try new things

- Repetitive behaviors

- Strong needs for reassurance

- Socially disruptive

- Family history of anxiety

Continuing on, we are going to talk about red flags. Red flags for clinical or more concerning anxiety are somatic symptoms, stomach aches, headaches, pain, and gastrointestinal issues. There is no organic medical cause for them. They might have difficulty falling asleep due to excessive worry. From my perspective, this is a big one. This is a huge one. I think that sometimes this is even the first red flag we catch.

This is the first clue that something might be up: very often, kids with anxiety struggle with sleep. Nighttime fears are most common, and it presents most heavily between the ages of six and eight. It is interesting. We associate that back with those real-world worries they are starting to have. I think these kids are busy during the day, but the second they lay down in bed and all is quiet around them, they start to have these worrying thoughts. They start to think about these things and become anxious, affecting their sleep.

The same goes for recurrent nightmares. I am not talking about the kiddo that has a nightmare every blue moon, maybe once a month, once every few months. The kid who asserts that they have nightmares every night but cannot tell you what they are about or does not talk about it all that much. They only say they do. I am talking about children who have regular and recurrent, and distressing nightmares, which is a certain red flag for anxiety.

Persistent school refusal and problems. I like to think of this more as school resistance. Refusal, as we are staying with the theme of typical versus concerning, I think it is typical when my kids have groaned in the morning now and then, maybe more often than not, "Ugh, I do not want to go to school, I do not want to go to school," but then they groan and trudge on through their morning, and they go. My kids are small. My oldest is in kindergarten. I know she is happier within 30 seconds of getting into the classroom.

School resistance and refusal, these are not kids that are moaning and groaning in the morning. They are almost impossible to get out of bed. The parent cannot get them to move through that morning routine to get into or out of the car. They are visibly distressed and resistant to going to school because many causes of anxiety could happen in school. It is very individualized, but again, we want to pull apart this like moaning and groaning versus these children that genuinely refuse or are resistant toward going to school in the morning.

Another red flag is an inability to concentrate. Kids with anxiety can report struggling with attending to something or concentrating. It is important to pull this apart from attention deficit attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or an executive functioning concern. Some school staff sometimes struggle to pull this apart because they look out at the classroom and see the kid over there. The teacher might think it is a more typical executive functioning deficit when this child is anxious. Whether it be what is being presented in front of them on the board or whatever tech they use, this generalized worry that they are having is just too stressful, so they are over here or there thinking about something a little more relaxing or something that comes to their mind, and they do not even remember what we talked about.

Sometimes worry thoughts are uncontrollable, but they are here. It is not based on executive functioning. It is based on anxiety. Another one is a reluctance to socialize or try new things. Maybe they have repetitive behaviors. We are pointing to pediatric OCD here, tapping, counting, and asking the same question repeatedly. That is that reassurance seeking. Parents always say this to me, "Gosh, he asks me the same thing every day or multiple times a day." He knows the answer. Who is going to pick me up from school? It is always me, I am always the one going to pick you up from school, but Johnny asks me every day, "You picking me up, you picking me up?" That is a massive red flag that sometimes parents can think is an annoyance, but in reality, it should be a red flag. It can be socially disruptive. A family history of anxiety is like a hereditary gift that keeps giving. It is not a linear presentation. When I say that, I mean dad has OCD, and the kid has OCD. The dad might have a specific phobia, and the kid might have separation anxiety, OCD, or selective mutism. It is the little hereditary piece of anxiety, not necessarily the specific diagnosis.

What’s the Problem with Anxiety?

We talked about how anxiety is sometimes normal and helpful, so what is the problem? It affects 9.4% of American kids and adolescents. Anxiety is one of the greatest predictors of other mood disorders, chronic depression and alcohol abuse in adulthood, and anxiety in children if left untreated. Again, we have now pointed to the fact that this is not a stage if it is clinically concerning. It is not a phase, and they are not going to grow out of it. In all likelihood, they are not going to age out of this. They need treatment. They need help in some form. If left untreated, it can predict other mood disorders, depression, and alcohol abuse. Of more than 40 million adults in the United States, which is 18%, have reported anxiety that is disabling for them. It is impacting their lives. Pediatric anxiety can turn into adult anxiety, and that number doubles if left untreated.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

We are going to get into these specific diagnostic pictures. These are little snapshots of different types of pediatric anxiety. The first one we are going to start with is Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD). What is generalized anxiety disorder? It is excessive and exaggerated anxiety about everyday events with no reason for that worry. They tend to expect disaster or worst-case scenarios. In kiddos, the anxiety is often focused on performance in school or sports. Am I going to pass the test? What if I do not play well? Will I get into a good college? It might drive extreme studying. I will study well for my test, but I will study all night and not sleep.

Ordinary Worry vs. GAD Worry

One might say that a kid with generalized anxiety is their own tyrant. They are bossy, and that is what it looks like. The anxiety can impact a kiddo's quality of life and their ability to participate in social activities in school. Signs and symptoms of this would be if the child might have GAD if they worry incessantly about everything. All the small things, particularly their performance in school or other activities or their ability to meet expectations. They tend to seek reassurance to assuage their fears and worries. Examples of this could be, will we get there on time? Who is picking me up? What if I cannot fall asleep? They ask these things potentially over and over again, or they are just consistently asking these questions for reassurance. Their anxiety can make them seem rigid, maybe even irritable and restless. I think that a lot of the time, we have this picture in our mind of what someone with anxiety should look like, and it is like curled in the fetal position, shaking, crying. It is a caricature of anxiety, but particularly for small children, the presentation can be varied externally. These kids can be irritable and restless. I know myself personally if I am irritable, and I am much more likely to snap at my husband in the morning when I am very anxious about something. I think expanding what that external presentation can look like can be helpful. It can also lead to physical symptoms, including fatigue, stomach aches, headaches, GI symptoms, frequent trips to the bathroom, and difficulty concentrating. They may have difficulty falling asleep or maintaining sleep. Keeping on with our theme, we are going to pull apart ordinary worry versus generalized anxiety worries.

Ordinary worries lead to planning and problem-solving, whereas chronic worries interfere with problem-solving and planning. In ordinary worry, their attention is focused on developmentally important issues. In chronic worries, the attention is focused on unlikely disasters. Ordinary worries do not interfere. Chronic worries crowd out ordinary activities. Ordinary worries end with choices made and actions taken. I am feeling a little nervous. What should I do about this? In chronic worry, worries are not solved, repeated, and replaced with other worries. I sometimes refer to this as whack-a-mole worries, one goes away, and another pops up. It is the focus of the child's life.

If we look at ordinary versus more chronic concerning GAD worry, examples of this would be ordinary being before the first day of preschool, the kiddo feels a little bit nervous. They maybe take a little bit longer to fall asleep that night. They need an extra hug from their parent before getting into the room. Another example would be a toddler crying when their parent drops them off at daycare, but they can calm down. It is my kid, my kindergartner. She is maybe a little bit upset going in, but within 30 seconds and a hug from mom, totally fine. While chronic worry is the differentiation, the kid with much anxiety about going to preschool complains of tummy aches every morning that are real, or they beg their parents to let them stay home throughout the school year. Again, this is not the "ugh, school," it is the kid who is begging to stay home. Going back to the toddler who is distraught when they are dropped off at daycare, they cry the entire day and cannot be comforted by the teacher they love. It is not the kid who recovers and a little bit of time. It is the kid who cries all day long.

Separation Anxiety

- Great difficulty separating from parents/caregivers

- Typical between 1 - 2 years of age

- Inhibits daily functioning

- Does not get better with time/experience (APA, 2022)

We are going to move on to separation anxiety with the little ones, where we see this most often. They have great difficulty separating from their parents or caregivers. It is most typically present, ebbs, and flows in infancy and toddlerhood. We typically see it most between one and two, and it inhibits their daily functioning. It, again, does not get better with time and experience. I am going to come back to that many times. This is not something we will see if it is typical separation anxiety. They are going to age out of it. As I said, separation anxiety will pop up if you have had an infant or a toddler and you know these kids well. It crops up and goes away developmentally appropriately through infancy and toddlerhood, even a smidge in early childhood. It comes and goes and comes. It is present and does not go away when it is clinically concerning. It does not get better.

Specific Phobias

In the next one, we are going to get into specific phobias. This is probably the most characterized fear and anxiety we see in media, TV, and movies. What is a specific phobia? What are specific phobias? They are disorders characterized by an excessive and irrational fear of an object or situation that is not normally considered dangerous. Children with specific phobias aren't anxious in general. They are only worried and anxious when confronted with that particular thing that causes them to fear, the terror. The confrontation can be direct or indirect, whether it is dogs, the dark, clowns, or loud noises. The thing itself, or even a song about it. For instance, they see it on TV, hear about it, and someone else is talking about it, and they do not have to be confronted by the big dog. Someone is just talking about their big dog.

Children with specific phobias are going to anticipate and avoid the thing that triggers their fear, which can then interfere with their normal activities. Adults and adolescents realize that their fear is unwarranted. Kids might not be able to do that. Some common childhood-specific phobias would be the natural environment ones, that category of the natural environment, storms, water, and heights. The next category would be animals, insects, creepy crawlies, big dogs, dogs in general, or cats. Then lastly is blood injury, I do not know about you, but my children have never been like, "Yippee, doctor, I would love getting shots." Blood injury phobias are mostly needles, seeing blood, or fear of other medical procedures. It is important to pull this apart. There is the typical fear most kids do not love going to the doctor for shots, but they are able to do it. They get their lollipop, and they move on. Pulling this apart with a kid who will not go in, I cannot get them out of the car seat, I cannot get them out of the car. They are screaming. We cannot get it done. Pulling it apart, always pulling it apart. Other signs and symptoms of a specific phobia avoiding things that they fear, dogs, water, and bugs. They might cry or throw a tantrum. Physical symptoms might be present, like trembling, dizziness, and sweating.

Social Anxiety Disorder

The next diagnosis is social anxiety disorder, a fear of social situations. This is a condition that is characterized by excessive self-consciousness, much self-consciousness that goes beyond shyness or just general nerves. I think everyone has periods and bouts of shyness. This goes way beyond that. Kids with social anxiety disorder are worried about being judged negatively by others and terrified of doing or saying something that may cause humiliation. The fear feels uncontrollable, even though older kids often realize their preoccupation is not reasonable. Older kids sometimes say, "I know this is ridiculous, I know that this is not going to happen, but I cannot get past it. I am still fearful."

There are two main types of social anxiety disorder, which I feel are not always known. There is number one is performance anxiety disorder, performance-based social anxiety disorder, which includes things like speaking in public, ordering in restaurants, and shopping in stores. There is a more interactional variety flavor of social anxiety. These are social situations, even when you are not in the spotlight. Children with interactional social anxiety might fear going to school, eating in public, and using public restrooms. Most people with interactional social anxiety might also experience performance social anxiety. What do we know about the onset of social anxiety? It is most common in adolescence and can happen in early childhood. We see it most often in adolescents. If left undiagnosed and untreated, it can lead to isolation and depression. When kids experience this, we are going to talk about selective mutism in just a second. Kiddos who have intense social anxiety, smaller kids, little kids that have selective mutism, they might be aware of it when they are younger, but as these kids age, they get into middle school and high school, we do often see the depression coming alongside it, because these kids are more aware of their limitations, these are kids who want friends, it is not that they do not want friends, it is that they want friends, they want to interact, they want to be social, but they are held back by their anxiety that they cannot, and that unsurprisingly can lead to depression as well.

Signs and symptoms then of social anxiety. You might suspect social anxiety disorder if your child or if a child is inordinately fearful of criticism, and again, I think most kids can be a little bit sensitive to criticism or getting in trouble, but again, I think you pull it apart by the kid who becomes distraught or just overly emotional or super emotional, uncontrollable from criticism. Kids with this disorder often express their anxiety by asking, "Well, what if I do something stupid? What if I do it wrong? What if I say the wrong thing? What if they think I am dumb?" Some kids tend to ask these questions a lot. Young children sometimes throw tantrums and cry when confronted with a situation that terrifies them, and their behavior can be misunderstood as oppositional. The fear they experience can trigger physical symptoms such as shaking, sweating, and shortness of breath, which could interfere with their daily life. They may have a full refusal to speak in front of others. If you think about giving a presentation in front of the class, reading at story time, et cetera, they might isolate themselves in the cafeteria or at recess, those unstructured times when they are meant to be socializing, they might isolate themselves that they are able to avoid the thing that makes them anxious, which would be the peers when they are in group events, they either engage in solitary activities, as I said, or they speak very, very little, maybe they are just answering questions that are directed toward them, but they are not spontaneously engaging in speech. They may avoid movie theaters, and restaurants, going to unfamiliar places, or being with unfamiliar people. They do not tend to love crowds in crowded places.

Selective Mutism (SM)

- An anxiety disorder in which a child is unable to speak in some settings and to some people

- May seem like the child is willful and refuses to speak, but the child experiences it as an inability

- Parents often notice signs of SM when a child is 3 or 4 years old; may not be diagnosed until the child goes to school (APA, 2022)

Social anxiety disorders mean a more severe cousin, selective mutism. This is a diagnosis that personally at Thriving Minds, we work a ton with. It is a diagnosis when I speak to people in the general public that is not just widespread. When we have trainees come to us, they have almost never worked with kids with selective mutism or been trained to work with kids with selective mutism, but I think as time progresses, we are seeing this become a little more well-known, a little more understood, which is wonderful, because I do think that it is a diagnosis that can be overlooked or misdiagnosed or confused with other things often, and the treatment is very specific for it. What is selective mutism? Selective mutism is an anxiety disorder in which a child is unable to speak in some settings and with some people. The child with SM typically, not always, talks very normally at home, for instance, or if they are alone with their parents somewhere. They are in their comfortable bubble. These kids are more often than not described as chatterboxes. They never stop talking. They are going, going, going, going home, but they cannot speak at all, and it is not that they will not, they cannot, they are unable to speak or above a whisper, for example, in other social situations, in school, in the community, with the public, with extended family members. Again, chatterboxes at home when they are in their comfortable bubble with their comfortable people, talking all the time or like normal, but then the second they are outside of that bubble, they are unable to speak, unable to communicate with others due to anxiety. Parents and teachers, this is the issue. Parents and teachers can sometimes think that this is willful. They refuse to speak, do not want to speak, do not speak, or speak loud enough to be heard, but the child, what they are experiencing is an inability.

It is important to think about how we discuss these children and how we write about these children when we write up clinical reports here about children with selective mutism. When editing a trainee's report, I go through them with a fine tooth comb because I think it is important when we discuss that Johnny will not speak in public with his friends. That is always something I circle, and I say, "This should not say will not communicate, will not speak to friends. It is cannot, or is unable to." Such a strong myth of selective mutism must be that this is willful and intentional. It could cause severe distress. These kiddos cannot communicate even if they are in pain or say they need to use the bathroom. It prevents them from participating in school and other age-appropriate activities. It is not uncommon for us to have families that come to us young children saying, "Oh, Johnny has accidents in school once a week because Johnny cannot ask to go to the bathroom." They need to talk to someone. It breaks my heart that sometimes these kids get hurt on the playground, fall off the monkey bars, and skin their knees, and a teacher does not see it, and this kid cannot communicate it. They are unable to communicate that they have hurt themselves, and not until they get home that night and a parent sees the big scrape on their knee does it come out. It is important to remember this is a "cannot," not a "will not."

It should not be confused with a reluctance to speak, a child adapting to a new language, or shyness in the first few weeks of school. That selective mutism is common in kids with English as their second language or some other speech delay. The way that we pull that apart is that it is not a familiarity with the language. This kid, while French is their primary language, is fluent in English, and they can speak in English with their comfortable people. This is non-unfamiliarity, a discomfort with the language. It is anxiety based. We can pull that apart. Signs and symptoms, if your child suffers or suffers from selective mutism, they might be freely verbal and gregarious at home. I would describe them as a chatterbox sometimes, but completely or mostly nonverbal at school. Some kids feel and seem paralyzed with fear when unable to speak. They have difficulty communicating even nonverbally, even sometimes just like the cashier at the store, "You having fun today?" Even this sometimes is difficult for them, and they cannot do it. They cannot nod or shake their head. Others will use gestures; sometimes, they can use facial expressions and nod if they cannot speak. Even in the home, some will fall silent if someone other than a family member is present. They are in their comfortable bubble, but mom's friend Sally comes over, who I do not know. I am turning it off all of a sudden because I am anxious, and I am unable to speak in front of this unfamiliar person.

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

The next diagnosis that we are going to talk about is pediatric OCD. I should say the last one we are going to speak about is pediatric OCD. What is OCD? it is an anxiety condition that plagues a person with unwanted thoughts, images, and impulses called obsessions. They are impossible to suppress, causing great anxiety, stress, and worry. They develop repeated ritualized actions called compulsions to alleviate the anxiety caused by these obsessions. Obsessions without compulsions, while rare, are present. Sometimes, we hear kids talk about these distressing thoughts or images, and we seemingly cannot find the compulsive behavior associated with them rarely but present. The disorder can manifest as early as five, but a child might lack the self-awareness to recognize the thoughts and fears, and they cannot recognize that the thoughts that they are having are exaggerated or unrealistic. They might not be fully aware of why they are compelled to perform a certain ritual. They know that it makes them feel like just right is the way that we phrase this, or they phrase it often, momentarily. Later on, magical thinking could emerge. We all experience some magical thinking to an extent. We might avoid crossing a black cat walking under a ladder if we think about societal superstitions. I used to live in New York City, and there are rarely 13 floors in buildings that adults created. We are superstitious about breaking mirrors, but people with OCD have more intense reactions to them. They avoid them more frequently, and they are more disruptive to their lives. For example, though we know an idea potentially is farfetched, a child finds themself being compelled to scratch the shoulder. If they scratch the left, I have to scratch the right. If I scratch the left, it has to be, and I cannot think of the word. It has to be the same on both sides and symmetrically is linked to my parent's safety. If I do not scratch symmetrically, mom is going to die in a car accident. These are the things that seem seemingly unlinked that can be linked by anxiety or by OCD,

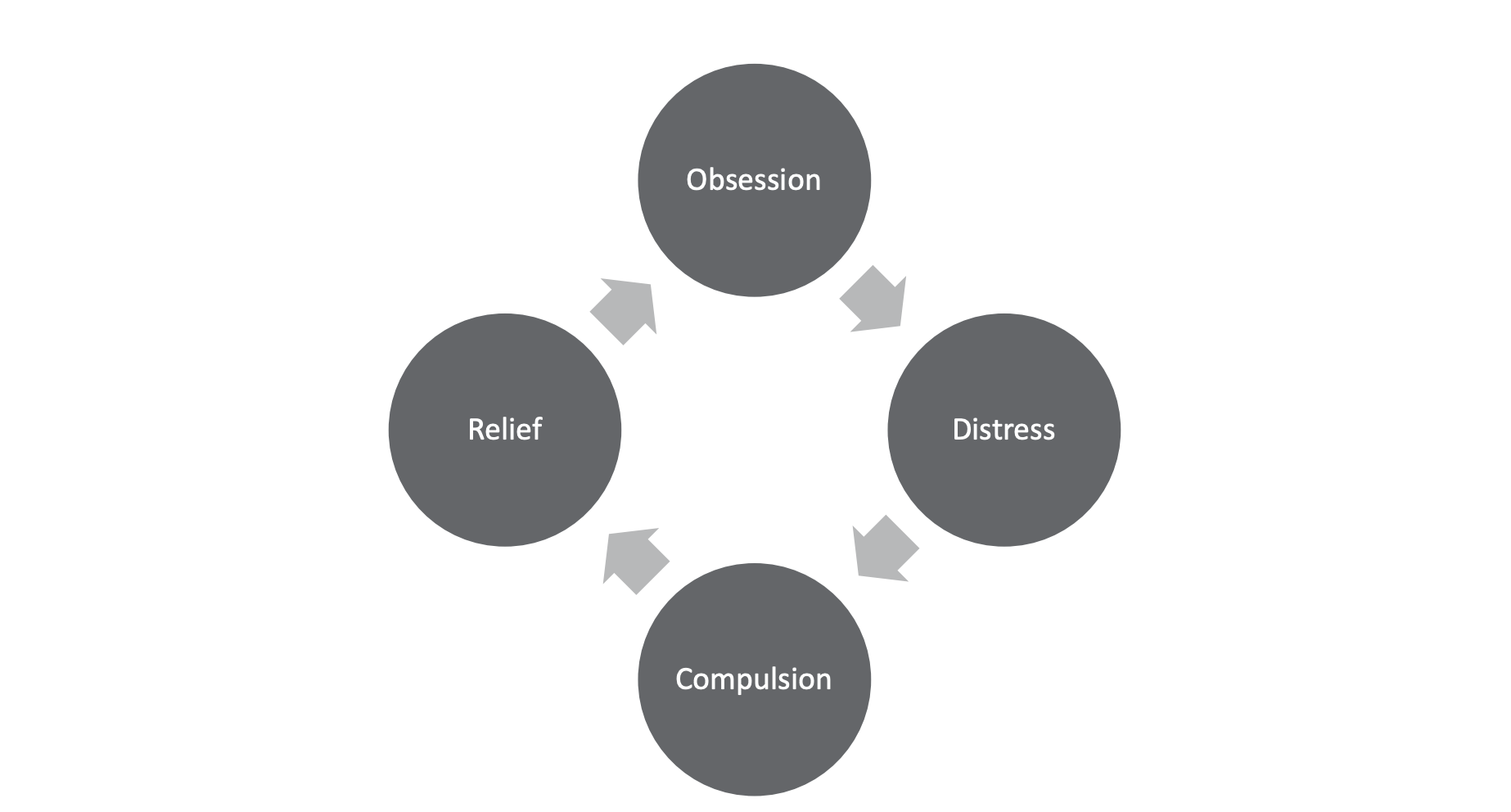

How OCD is Maintained

Figure 1. The cycle of OCD (Puliafico & Robin, 2017).

Figure 1 is a diagram of how OCD is maintained. I use this analogy often with kiddos called the "bug bite." These are things that we do not just do once. Usually, we do it over and over and over again. If I have this obsessive thought that I need to scratch symmetrically, we are going to stick with that example. My compulsive behavior is doing this, and I do it. I scratch symmetrically on both sides like I scratch a bug bite. It feels better for a moment, and then it comes back again, and I have to do it again. I feel better, and then it comes back again.

Let's talk about how OCD is maintained. Again, we stick with this example, the obsessive thought is like, scratch symmetrically, or your mom dies, or your mom's going to have a car accident. I feel distressed. I feel very, very distressed. "Oh my God, I do not want that to happen." I engage in compulsive behavior. I scratch symmetrically three times on both sides. I feel much better. I feel relief, mom's safe, mom's fine. If we understand this to be correct, the obsessive thought is going to come right back around because I am continuing this loop. It will keep looping over and over again, just like the bug bite's going to keep itching and itching and itching and itching again. Spoiler alert: we will talk about treatment in about a couple of minutes. We have to break the chain. We have to stop itching for the bug bite. The bug bite's never going to go away unless we stop itching it. We have to stop engaging in the cycle to make it go away.

How Anxiety is Maintained Through Escape and Avoidance

The other way in which we maintain anxiety is through escape and avoidance. Avoidance is oxygen. Escape and avoidance are the oxygen of anxiety. If you think about a fire, it is the thing that keeps it going. It stokes it and keeps it going. Avoidance keeps kids from learning that their fear is a warning, not a prediction. It is not necessarily going to happen. It gets in the way of them learning that just because they think something does not mean it is going to happen. Avoidance becomes the default way of responding to the world and teaches kids to steer themselves away from unpredictable or uncomfortable situations. We think, "Oh, Johnny's afraid of spiders, I am always going to squish them away. What is the problem with that?" We are slowly teaching Johnny that if something makes him uncomfortable, he should stay away from it. They generalize these things. These are lessons that we are teaching to them. We will get into this more when we talk about treatment and the things we are targeting when we talk about pediatric anxiety.

An Introduction to Evidence-Based Treatment for Anxiety

Let's talk about evidence-based treatment for anxiety, the gold standard for treating anxiety. I cannot say it enough. This is like the introduction. This is the skeleton of it.

Our Goal in Treating Anxiety….

Our goal in treating anxiety is to teach kids how to face their fears. We also want to teach them that when something feels hard or scary but is not dangerous, the more we practice doing it, the braver we become, and the easier and less scary it becomes. We are teaching bravery. We are not teaching them not to be fearful. In anticipating giving this presentation today, I asked my five-year-old who was the bravest person she knew, real or fake. Unsurprisingly, it was Elsa. Elsa is the bravest person she knows. I said, "Why?" "Elsa's not afraid of anything."

Dr. Mom clicked in and said, "That is not true." Very kindly, very politely, that is not true. Elsa is afraid of things, but Elsa is afraid and then does things anyway. She knows that it is worthwhile, and just because she feels scared does not mean there is danger. She does it anyway. The opposite of fear or bravery is not fear. Being brave is being fearful and doing it anyway. We want to practice being brave and building up our brave muscles, the language we use with kids.

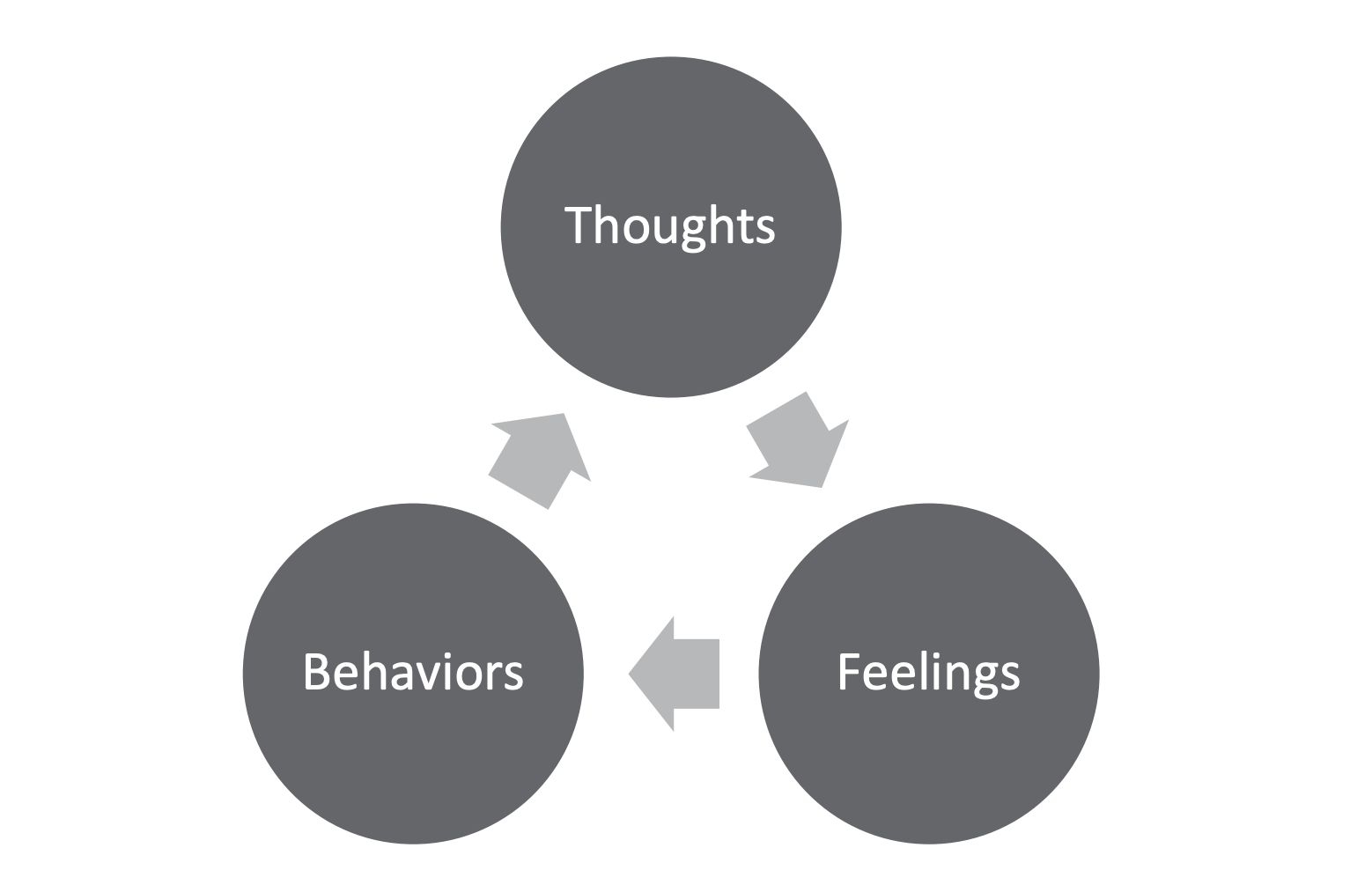

The Cognitive Triad

Finally, teaching kiddos that being brave is not a feeling, you can feel scared, but you can act brave. With kids closer to five and older, I want to say even maybe older than five. You can also explain that when we feel scared, there is nothing dangerous. We can get into this a little bit more, it is like when the fire alarm goes off at home, but there is not a fire. It is just the toast burning. It is like, the popcorn that I burnt in the microwave again. When we have scared feelings, but there is nothing dangerous, we do not have to run away to safety. We can ignore that feeling, just like the fire alarm goes off when it is toast burning. You do not have to run out of the house. You have to turn the fire alarm off. We are effectively helping them learn to turn the fire alarm off when it is just mom burning the popcorn again.

Figure 2. The Cognitive Triad (Stallard, 2009).

Figure 2 is a diagram of the Cognitive Triad. The crux of treatment is the cognitive triad. I was looking through these this morning and realized these arrows should be going both ways, but to be honest, I am not that savvy with PowerPoint, so I did not do it. The cognitive triad is thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and any emotion, but in this instance, anxiety affects how we think, feel, and do behaviorally. These arrows should be bidirectional. They all impact each other. When I work with children, I tell them the good news. If we affect any of these, if we change any of these, it is going to make them all better, but great news, I am going to teach you how to fight all three of these, I am going to teach you how to work with all three of these, and this is the basis of our work.

Thoughts and Reframing

Let's talk about the first one, thoughts. Anxiety affects us in the way that we think. I am going to use the example of potentially my very real fear of large dogs. It is going to be the through line that I use. If I am fearful of dogs and walking down the street, and my neighbor with their gigantic horse dog is walking in front of me, I might think, "Oh my God, it is going to bite me. Oh my God, it is going to kill me." When in reality, the dog is on a leash, and it is totally fine, and it has an owner, but that is going to be the thought that goes through my mind, "Oh my God, the dog's going to bite me, it is going to kill me."

We are going to try to empower kids to talk back to anxiety through "thought challenging," which is what we call it. Often with kids, and to be honest with adults, we want to teach them how to externalize their worry. This helps destigmatize, take away the shame, and it helps give them someone to fight with rather than fighting themselves. We call this the "worry bully" often. They can give it whatever name they want. We want to tell it no, and we want to challenge these thoughts. We challenge thoughts by identifying anxious and unhelpful thoughts. We ask ourselves, what else could this be? What else could happen? What would I tell a friend? This is my favorite, and even if it were true, could I cope? The dog is walking across from me. What else could happen? Well, it barks, and the owner pulls it back. What would I tell a friend? I would tell a friend it is cool.

You will be fine. Look, there is an owner, and if it were true, could I cope? If the dog bites me, I probably would not be thrilled, but I would not die. I guess and create a more accurate replacement thought. my then replacement thought for that, I am walking down the street, I am thinking the dog's going to bite me, I ask myself all these thought-challenging questions, I am going to flip it, and I am going to say, "I am feeling afraid of the dog, but in reality, there is an owner, the owner is not going to let this dog bite me probably." Still going to sit with a little bit of fear little bit of probably, but I have challenged myself. I have looked at the odds, I've looked at the reality of the situation, and I have looked at the facts around me. That is how we challenge thoughts in that little triad.

Relaxation

We will talk about physiological relaxation. What I like to refer to as the holy trinity of relaxation. We always, and any book, any manual you come to, always talk about these three, diaphragmatic breathing, taking deep breaths, and visualization. You will learn how to do it in 57 different ways. There is lazy eight breathing. There are 4, 7, and 8 types of breathing, which is not even all. I always come back to that there is no right or wrong way to do this as long as it is deep. I teach kids to breathe in through their nose and out through their mouth; the inhale should be shorter than the exhale. It is in for three, out for five, in for five, out for seven. Personally, I think we are giving them something to focus on, and yes, getting more oxygen, getting them to slow down, does physiologically relax them. Progressive muscle relaxation, there are all sorts of great scripts out there to help kids relax their muscles. Progressive means we are going piece by piece to relax their muscles, and then visualization. This is any guided visualization and imagery you have heard on an app, podcast, or YouTube. You imagine yourself on a fluffy cloud. These are things that slow our bodies down. I am not going to get into the real technical, biological pieces of this and all the, I am not going to get into that, but these are the things that slow our body down.

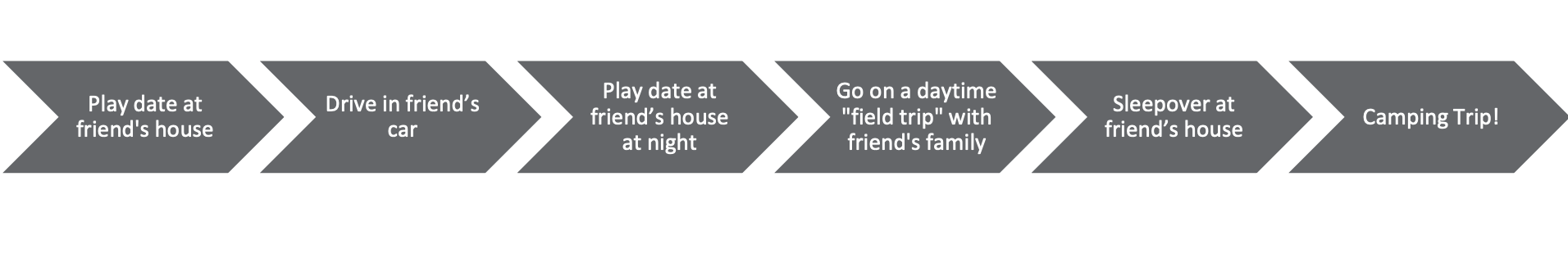

Fighting Escape and Avoidance

- Create a measurement tool for worry – like the fear thermometer (stoplight for younger)

- Take small steps toward success

- Ex: Going on a camping trip without parents

Figure 3. A diagram of fighting escape and avoidance ((Stallard, 2009).

Figure 3 is a diagram of fighting escape and avoidance. The last piece on the triad is what they do, the behavior. When we are anxious, the behavior that we most likely engage in is escape and avoidance. The opposite of that is confrontation and exposure. this is usually what we engage in. We want to create a measurement tool for worry, like the fear thermometer. I am sure that a lot of people have seen that, that zero to 10, or you think about that imagery in the doctor's office, like how bad does it hurt? If they are younger, we could do a simple stoplight, green, yellow, or red. We want to take small steps toward success. When people hear exposure, when they think about these things, they think of it like clockwork, orange is a room full of tarantulas, but that is not what exposure is.

It is this gradual graduated process where we are taking small steps towards success. In Figure 3, the big goal is going on a camping trip with a friend without your parents. The small steps we will expose ourselves to, the small steps we will take is going on a play date, just like a little hour-long play date at a friend's house. Maybe the parent is there for the first step, or maybe the parent's not even there for the second step. We are then going to drive in the friend's car, the friend's parent will drive us, and we will have a play date at the friend's house at night. It is dark, getting close to that bedtime stuff. We are going to go on a daytime field trip with a friend's family. We are going to spend the whole day with that friend's family. Then we are going to have a sleepover at that friend's house. We are going to stay all night, and then once we have done all these things, we can go on the camping trip. These are all incrementally smaller things that the child would rate the first few as, like a green light, the middle ones would be yellow light, and the later ones would be red light. They build confidence as they climb the ladder to do that big goal at the end, that camping trip.

Caregiver Behaviors Associated with Anxiety

- Overcontrol – intrusive parenting, exerting control in conversation, limiting of authority and independence

- Overprotection – excessive caution and protective behaviors without cause

- Modeling of Anxious Interpretation – agreeing with child’s distortion of the risk in a situation, reinforcing the idea that normal things in the world are too scary to approach

- Tolerance or Encouragement of Avoidance Behaviors – suggesting or agreeing with not trying something difficult

- Rejection or Criticism – disapproving judgment, dismissive, or critical behavior

- Conflict –fighting, arguing, and disharmony in family associated with higher levels of anxiety (Dacey et. al., 2016)

Last, we are going to talk a little bit about parent work and parent coaching for anxiety, a huge piece of pediatric anxiety is working with the parents. Not going to get into this super in-depth today, but we are going to talk about it. There are caregiver behaviors associated with anxiety, overcontrol and intrusive parenting, exerting control in conversations, limiting authority and independence, overprotective, and excessive caution and protective behaviors without cause. Modeling of anxious interpretation, agreeing with the kids' distortion of the risk in the situation, reinforces the idea that normal things in the world are too scary to approach. Another is the tolerance or encouragement of avoidance behaviors, suggesting or agreeing that we should not try something difficult. "Oh, you do not want to play soccer. It is too hard. No worries, we are not going to do it." Teaching them to say, "That is hard. Let's not do it." Rejection or criticism, unsurprisingly, disapproving judgment, being dismissive or having critical behavior, and then high conflict tends to make anxiety worse or have anxiety present. Fighting, arguing, and disharmony in the family are associated with higher anxiety levels, which is unsurprising.

Positive Caregiver Behaviors that Buffer Stress

On the flip, positive caregiver behaviors buffer stress, rewarding coping behavior, focusing on means and not ends, and rewards. That means, as you have tried, it was hard. You tried rewarding taking on challenges, recognizing partial success is a big one. Extinguishing excessive anxious behavior. We want to reduce as parents. We want to reduce anxious behavior by not responding to it excessively, either with concern or anger. That is not giving a lot of attention to the child's anxiety. We want to manage our own anxiety. This is a tough one. We want to limit displays of distress. We do not want to introduce parents' worries to the mix. I talk to my spouse about this all the time. The man is terrified of spiders, making both of our children afraid. I constantly talk to him about engaging in brave behavior in front of them because he is teaching them to be afraid of spiders, but we can also develop family communication and problem-solving skills. We have an open house policy for positive communication and problem-solving opportunities. We want to be communicative about these things. Then, of course, we always come back to that authoritative parenting. The democratic parenting style that directs child's behavior while valuing their independence is warm but firm and associated with lower anxiety levels and self-confidence.

Parental Rescue and Accommodation

- Parental Accommodation – refers to parental behavior modifications that attempt to prevent or reduce child distress associated with participation in age - appropriate activities and/or exposure to feared or avoided stimuli

- Works similarly to escape/avoidance

Next, we are almost done, is parental rescue and accommodation, this is a big concept that we are literally going to scratch the surface on, parental accommodation is to find, it refers to parental behavior modifications that attempt to prevent or reduce the child's distress associated with participation in age-appropriate activities and or exposure to feared or avoided stimuli, it helps, it works similarly, pardon, to escape and avoidance, I just said these big words, I just said this weird definition, the most concrete example of parental accommodation that I can give you that I give to all parents is that child who has contamination-based OCD and is just washing their hands over and over and over and over again, parents are going to Costco, they are going to Costco and they are buying the barrels of hand soap and they are just saying, "This makes Johnny feel better if he washed his hands over and over again, I am naturally just going to keep giving him soap, giving him soap, giving him soap." Again, scratching the surface of parental accommodation because it is a big heavy topic.

How Parents Can Help

Parents have to understand that accommodating distress is very natural. When our kids are struggling, we want to take that from them. We want to hold that for them, it is understanding, and as clinicians, it is important for us to impart this to parents. It is natural, it is understanding, but it is more useful. It is more helpful to allow your child to sit in distress. It is more helpful to support them and allow them to learn that they can do hard things. Does this mom need to all of a sudden have no soap in the house? No, think about that ladder again. We can do it in small ways, and the parent can stop accommodating little by little.

I wrote down a couple of my most frequently asked questions when I give a presentation similar to this that I will get to with my ticking down the last few minutes. One of the questions I get when I talk about this with parents is that clinicians need to know how to talk with parents. They ask, "How do I sit there while my child struggles?" I only get a little bit of parental help. They always say, "What do you want me to do? How can I sit there while my kid struggles?" As clinicians, we can coach them that it is not black and white. I think that they think that if we are not saying, "You are not hugging and cuddling and comforting them, or saying you are fine," then I am telling them to stand in the corner to point and laugh.

I think is just one end of the spectrum or the other. It is not that black and white. What we can say is the magic statement. We can have parents use a combination. It is an equation of empathy plus encouragement, "I understand that this is difficult for you. I see that this is hard, or I see that you are scared right now, but I know you have got this. I know you can do this." Empathy plus encouragement and also modeling brave behavior goes a long way. If we get into the habit of modeling brave behavior in front of our kids, we will know better what to help them do in these moments. When my husband is confronted with a big spider, he says, "Oh, I am pretty scared of this spider, but I know I can do this. I know it is probably not going to hurt me. I am just going to pick him up and move him outside." He is going to know better how to help my child than when they are feeling a little bit anxious.

If anxiety is another one I get a lot of, parents always ask me this. If anxiety is hereditary and it is all over my family, we talked about how it is hereditary, "Are we just doomed, and should we give up now?" The answer is a resounding no, absolutely not. They are not doomed. Yes, they are more likely a child with anxious parents and anxious family members are more likely to have anxiety, but they are not doomed for it. I like to give the analogy of diabetes. While a child who has parents that are diabetic is also more likely to have diabetes themselves, parents can do many things to help this child live a healthy lifestyle. They can help them make healthy dietary choices. They can help them exercise. There are many things parents can do to either reduce the risk or the severity of their diabetes.

In the same way, as parents or clinicians, we can coach parents to help reduce the risk of anxiety to help reduce the severity of anxiety. Again, by all those things, modeling brave behavior, encouraging and rewarding bravery. Are we doomed that the kid might have it? No, we could prevent the severity of it, we can prevent it from popping up, and there are lots and lots of things we can do.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

Dacey, J.S., Mack, M.D., & Fiore, L.B. (2016) Your Anxious Child: How Parents and Teachers Can Relieve Anxiety in Children, 2nd Edition. Wiley-Blackwell.

Evans, D. W., Gray, F. L., & Leckman , J. F. (1999). The Rituals, Fears and Phobias of Young Children: Insights from Development, Psychopathology and Neurobiology. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 29(4), 261–276. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1021392931450

Lebowitz, E. R. (2020) Breaking Free of Child Anxiety and OCD: A Scientifically Proven Program for Parents. Oxford University Press.

Lebowitz , E.R. (2019) Addressing Parental Accommodation When Treating Anxiety in Children. Oxford University Press.

Puliafico , A.C., Robin, J. (2017). The OCD Workbook for Kids: Skills to Help Children Manage Obsessive Thoughts & Compulsive Behaviors. New Harbinger Books, Inc.

Stallard, P. (2009). Anxiety: Cognitive Behaviour Therapy with Children and Young People (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203098714

Citation

Roth, A. (2022). When to Worry About a Child’s Worries. Continued.com - Social Work, Article 191. Available at www.continued.com/social-work