Editor's note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, ADHD 101: Bringing Focus to the Confusion, presented by Alison D. Peak, LCSW.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Communicate the foundational symptoms of an ADHD diagnosis.

- Describe the process of making an ADHD diagnosis.

- Describe interventions in a classroom to support children with ADHD.

The Role of Diagnosis

- Diagnosis is an essential part of all health care services.

- All healthcare providers give a diagnosis at the end of a visit.

- This is what facilitates payment from insurance companies.

- Everything has a diagnosis (Pink eye, strep throat, questions about birth control, EVERYTHING).

- Diagnoses are made using agreed upon classification systems (ICD:10, DSM-V, DC:0-5).

- Diagnosis allows professionals to communicate a share perspective with minimal description.

Before we start talking about ADHD specifically, I wanted to talk about diagnosis as a whole. Diagnosis often has a bit of a misnomer within the mental health community, that we're always giving labels. Diagnosis is an essential part of all healthcare services, so it's not just a mental health thing. All healthcare providers give a diagnosis at the end of every visit, regardless of what you go to see a healthcare provider for. That could be everything from pinkeye to strep throat, or if you have questions about birth control. Everything has an associated diagnosis. The diagnosis code is what facilitates billing to insurance, and essentially, payment for services. In the behavioral health world, we have the same process. Our diagnoses may sometimes be a bit different or may look a little different in the way that we arrive at them, but just as with primary care providers, we are looking to make a diagnosis at the end of a visit and put it on paper so that it facilitates the reimbursement for that service.

Diagnosis across all health disciplines are made using classification systems. ICD-10 is the International Classification and Diagnostic summary. There are 10 versions, 10 being the most updated and what the world functions on at this point. All physicians function out of ICD-10. If you were to go to an ER while on vacation, they're going to use the ICD-10. It is the general understanding across the world of how we classify and understand spectrums of symptomology. The DSM-V is the psychological equivalent to the ICD-10. It spells out how we see all the behavioral health diagnoses and includes everything from sleep hygiene difficulties to schizophrenia and ADHD to autism. It is all-encompassing of what the general understanding of presentation for these sets of symptoms should be. There's also the DC:0-5, which is the diagnostic and classification for mental health and developmental disorders for children zero to five years of age. The ICD-10 covers in utero all the way through geriatrics, while the DSM focuses on diagnosing children with mental health disorders age five and older. When we're looking at our real young kids, the diagnostic manual we use is the DC:0-5. The diagnosis is about a general understanding. It is the way that we, as professionals, engage in communication and are able to share understanding with minimal description. Somebody can say, I see symptoms of hypervigilance, and everybody understands what that word means. I know how that translates, I now understand what that path of thinking is, and for us, it is about the process of how we facilitate services and how we make sure that other people know what our concerns for this child are, and what we hope for, as far as treatment goes.

- Ethical dilemmas in giving diagnosis to young children

- They’re still developing

- Their brains aren’t done growing

- They have a lot of life left to live

- It will go on their permanent record

- It means something is “wrong” with them

- The realities of a diagnosis

- At the end of the day diagnosis facilitates access to services

When we're talking about diagnosis with young children, we often see that there are additional thought processes that come into play and that people become a little anxious about the idea of giving a diagnosis to a three-year-old. There are all these concerns that kids are still developing, that their brains aren't done growing, that they have a lot of life left to live. Those are all accurate, but we don't hesitate to make diagnoses of strep throat based on the same metrics, like they still have a lot of life left to live, and they are developing. That doesn't change the fact that for the moment, their throat is red and swollen. The same thing is applicable when we talk about behavioral health. These diagnoses that we give are no more permanent than the diagnoses that occur in a primary care physician's office. Much like some of the diagnoses in a primary care physician's office, they can be. If a child is diagnosed with type I diabetes at age six, that's not going anywhere. We know that their pancreas is no longer going to produce insulin and that they will always need some form of dietary changes or medication supplement. There are behavioral health diagnoses that are like that, that we have to manage, and we're going to need to know how we interface and what we're going to do differently in day to day life.

The process and role of diagnoses in both worlds are very much the same. There also frequently is a concern when we talk about diagnosis with young kids that it will go on a permanent record. This is one of the urban legends I'm very happy to debunk. There's actually no such a thing as a permanent record. Medical records change so frequently and do tend to be dependent on provider and age of life and what the typical diagnosing pattern was at that time. Even when diagnoses are made in young children, this is not something that's going to be assumed to be their reality for the remainder of their life. It really can't be accessed unless someone is looking at their health record. Even then, health records tend to be so scarce in information that things are really hard to find. Colleges can't access this information, with the exception of psychiatric hospitalization. The military can't access that information. The military will know if there's been a psych hospitalization, but less than that, they don't even have the right to access that information. What we know is while there may be a lot of anxiety around that diagnosis, or around a child having a diagnosis, that at the end of the day, it facilitates access to services. Oftentimes, those services and supports are very much what we need, and what holds the gatekeeping for us to begin to make progress. We really want to be able to have conversations with parents, with other providers, and with educational staff around that this just helps us understand who this kiddo is. It doesn't change anything. They're the same child that they were yesterday, but now, we're going to have a shorthand way of being able to describe how we're all going to come together to move forward.

What is ADHD?

Diagnostic Criteria

Under the DSM V, a child with ADHD must exhibit:

Six (or more) of the following symptoms have persisted for at least 6 months to a degree that is inconsistent with developmental level and that negatively impacts directly on social and academic/occupational activities: Note: The symptoms are not solely a manifestation of oppositional behavior, defiance, hostility, or failure to understand tasks or instructions. For older adolescents and adults (age 17 and older), at least five symptoms are required.

- a. Often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, at work, or during other activities (e.g., overlooks or misses details, work is inaccurate).

- b. Often has difficulty sustaining attention in tasks or play activities (e.g., has difficulty remaining focused during lectures, conversations, or lengthy reading).

- c. Often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly (e.g., mind seems elsewhere, even in the absence of any obvious distraction).

- d. Often does not follow through on instructions and fails to finish schoolwork, chores, or duties in the workplace (e.g., starts tasks but quickly loses focus and is easily sidetracked).

- e. Often has difficulty organizing tasks and activities (e.g., difficulty managing sequential tasks; difficulty keeping materials and belongings in order; messy, disorganized work; has poor time management; fails to meet deadlines).

- f. Often avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to engage in tasks that require sustained mental effort (e.g., schoolwork or homework; for older adolescents and adults, preparing reports, completing forms, reviewing lengthy papers).

- g. Often loses things necessary for tasks or activities (e.g., school materials, pencils, books, tools, wallets, keys, paperwork, eyeglasses, mobile telephones).

- h. Is often easily distracted by extraneous stimuli (for older adolescents and adults, may include unrelated thoughts).

- i. Is often forgetful in daily activities (e.g., doing chores, running errands; for older adolescents and adults, returning calls, paying bills, keeping appointments).

- Often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, at work, or during other activities. Oh, I forgot my homework, every day for three weeks. Oh, my teacher handed it to me, and I got distracted and laid it down on someone else's desk. I once had a kid who frequently forgot his shoes at the pool. Again, if we stop and slow down, it is one thing to say, oh geez, I set that empty water bottle down and left it, but we generally don't walk places without our shoes without realizing that we have done that.

- Often has difficulty sustaining attention in tasks or play activities. We'll see kids rotate rapidly from one thing to another. They will often say, "I'm bored" over and over because their attention is moving so fast that they can't maintain focus on anything long enough to enjoy it. Everything is just moving like we've got a motor in us.

- Often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly. This is qualitatively. The essence of it is very different than I didn't want to do what you told me to, so I just didn't, or I'm ignoring you. Often, we see kids with ADHD who know they weren't supposed to do whatever that was, and then catch themselves after it's done. You might see them stop, and realize, oh, I did it. They know they weren't following through in the way that they wanted to. Another example is that they'll be looking right at you and you'll give them a list of three things to do. They may go and do the first thing then they come back and say, "I don't know what else you wanted me to do." Even though they have eye gaze and good, clear attention, they still are not able to follow through appropriately.

- Often does not follow through on instructions and fails to finish work, chores, or duties in the workplace. We talked about this a little already. It is a lot like the movie Up, where the dog would frequently get distracted by squirrels. They are very easily distracted by other stimuli.

- Often has difficulty organizing tasks and activities. This is a big one. Kids with ADHD have a very hard time putting things in sequential order. If you tell a kid, "Go upstairs, get dressed, grab your shoes, and get your lunchbox," then they may come back downstairs with the lunchbox and some underwear on, but they couldn't put themselves in the process of I must put on underwear, then pants, and then my shoes. They have a hard time getting the order and sequencing down to follow through. As kids with ADHD get older, they are generally quite messy and can be very overwhelmed by that. They really aren't intending to be disorganized, but the way that they organize is to leave everything out so they can find it quickly. It looks incredibly chaotic, but they can often reach in a pile, grab something, and say, "It's right here." You might be thinking, I don't know how you found anything in the midst of all of that. Time management is very difficult when we're talking about ADHD, including the ability to know how to get themselves started and paced to be finished on time. Due to this, we will see kids swing from one extreme to other of I either rushed through it so quickly I didn't really do good work, or I slowed down so much I never got it finished.

- Often, avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to engage in tasks that require sustained mental effort. Sustained mental effort is really key. Lots of kids with ADHD will play outside for hours, or they will watch movies, or they will play with LEGOs or Hot Wheels, or whatever their hobby du jour is. But those are things that do not require sustained mental effort for them. They actively find 150 excuses to not do the thing that's really hard. They always save math until last or randomly spilled coffee on whatever it was, and so now it's just not possible to do that. They work really hard to get out of doing the things that are hard.

- Children with ADHD lose things a lot. These are random things, not just the things that we are accustomed to, such as a lunchbox. Instead, it's their shoes. How did we forget your shoes? It's often large items that feel much more difficult to lose track of.

- Often forgetful and will lose themselves in space and time. They will be off to do something, get distracted, and then, when you call their attention, they're like, oh yeah! Then they'll get back on track because it's not malicious. They just are everywhere.

Remember, they had to have six or more of that previous list (#1) and then they must also have six or more of the following list (#2), that again, has been present for at least six months, is inconsistent with developmental level and trajectory, and has negatively impacted social or academic functioning. Again, it cannot be a manifestation of hearing difficulty, life change, other major events that are similar.

- a. Often fidgets with or taps hands or feet or squirms in seat.

- b. Often leaves seat in situations when remaining seated is expected (e.g., leaves his or her place in the classroom, in the office or other workplace, or in other situations that require remaining in place).

- c. Often runs about or climbs in situations where it is inappropriate. (Note: In adolescents or adults, may be limited to feeling restless.)

- d. Often unable to play or engage in leisure activities quietly.

- e. Is often “on the go,” acting as if “driven by a motor” (e.g., is unable to be or uncomfortable being still for extended time, as in restaurants, meetings; may be experienced by others as being restless or difficult to keep up with).

- f. Often talks excessively.

- g. Often blurts out an answer before a question has been completed (e.g., completes people’s sentences; cannot wait for turn in conversation).

- h. Often has difficulty waiting his or her turn (e.g., while waiting in line).

- i. Often interrupts or intrudes on others (e.g., butts into conversations, games, or activities; may start using other people’s things without asking or receiving permission; for adolescents and adults, may intrude into or take over what others are doing).

- We're going see kids with ADHD fidget or tap hands or feet or squirm all the time. They will often have kind of their own thing. Some kids will snap or they'll make clicking noises with their tongue. I have lots of kids who suddenly find a random sound that they like the noise of, and will repeatedly say it over and over and over again because it's this fidgety, hyperactive behavior.

Really has difficulty maintaining being seated. Sitting requires some focus of this is the thing I need to pay attention to, and if I'm distracted, then I'm probably going to get up and go do that, or I'm probably going to go over here and talk to this person, or I just couldn't wait any longer. Then it becomes a piece to manage. In really young children, we see this piece that ADHD is frequently accompanied by often running or climbing in places where it's inappropriate.

There is frequently, with ADHD, a sense of what we call precocious danger seeking, such as standing on the back of furniture. I have had kids pull out the drawers in chests of drawers and then use them as stairs to climb up. They like being on top of cars or on the hoods of cars. I recently did consultation for a childcare center where a child actually climbed a wall. They are so impulsive and so active that it must be bigger and better and more intense every time. It's not okay to just climb to the top of the slide and slide down, they're going to climb to the top and jump off.

Lots of difficulty engaging in things quietly. They tend to be much more talkative and tend to interrupt quite a bit more. They are frequently on the go. We frequently use the phrase, driven by a motor. It's almost as though kids with ADHD couldn't stop if they wanted to. It's as if they're so hopped up and going that they can't catch themselves, even when they realize what they've done. They can't make themselves slow down enough to stop and think through that process. Part of this impulsivity frequently gets manifest as blurting out answers. They don't do a great job of waiting their turn, raising their hand, or knowing that other people should get a turn. They just really, really want somebody to know what the answer is, and so they'll just interject.

Waiting turns is difficult, like I said. You'll see lots of interruptions, lots of intrusions, and lots of difficulty with personal space. They may be so very, very excited about this thing, that they got really close to you to talk about it. Another example is that they may really like you, and have only known you for 15 minutes, but they're going to give you a big bear hug and kiss you on the cheek. That's not socially appropriate, but they can't contain impulse enough to slow down and think through that.

We have to have six items from list one, six items from list two, and several inattentive or hyperactive symptoms have to be present before age 12. The symptoms also have to be present in two or more settings. This means we have to see behaviors at home and at school. You might see the symptoms at home and at church or at school and with the grandparents. It doesn't matter where it is, but it must occur in multiple locations and can't just be isolated to one.

There has to be clear evidence that there is this place of interference with quality of life, social interactions, and daily functioning. It must be outside of the developmental trajectory, it must have an impact, and we have to rule out all of these other pieces such as it can't also occur as a side effect of some type of psychotic episode in late adolescence and it can't better be explained by anxiety or PTSD or autism or hearing loss.

Six items in list one, six items in list two, plus B, C, D and E. That's a whole lot going on. There are times that we've got kids who are busy or they may be a lot to handle, but they may not have 12 items plus B, C, D, and E. It doesn't mean that they're not struggling to engage with their world or that something else may not be going on, but meeting the criteria for a diagnosis for ADHD is a bit more difficult than sometimes I am concerned we give it credit.

ADHD as a Diagnosis

- ADHD is often a difficult diagnosis to give or receive.

- It’s essential that difficulties exist in more than one setting and that the behaviors really be sufficient to warrant a long-term diagnosis.

- ADHD is a frequently given diagnosis is early childhood, but may not necessarily be reflective of the life journey of that child/family.

- In the 1980s, the (then) DSM-III identified ADHD as 2 diagnoses.

- ADHD

- ADD

- In 1994, the DSM-IV revised this to the current understanding that ADHD is a single diagnosis with 3 subclassifications.

- Predominantly Hyperactive

- Predominantly Inattentive

- Combined Type

- All children with ADHD will exhibit some hyperactivity and some inattentiveness.

As a result of that, ADHD is often difficult to diagnose and sometimes, that means it's a difficult diagnosis to receive. There are frequently trends in diagnostic behaviors in the behavioral health world. For a long time, in the late 90s and early 2000s, everything was ADHD. As a result, what generally happens is we swing the pendulum back the other way. Now, people are very wary to give ADHD diagnoses or to treat ADHD. There may be times that you're going to have kids who meet all 12 things, B, C, D, and E, and we're still struggling to find somebody who's going to help us get access to those services. We really have to decide if it is a diagnosable issue or is it a phase of life or a developmental piece or just a really bad day. It is imperative that those difficulties exist in those two settings, and that the behaviors are really sufficient to warrant that long-term diagnosis. It's not just a recent phase, but this has been going for long enough that we really are going to need more intensive intervention. At that point, with information and data for both settings and being able to demonstrate an impact on the child and duration of symptoms, then the diagnosis will often come. So that might be something to conceptualize as you have conversations with families or your own concerns are raised around this topic of ADHD. The behaviors may not have been of concern for long enough or there may be a pediatrician who says, let's wait and see because it's only caused one incident at school and not three or four. That may not mean that we're not on a trajectory, but that we have not incurred enough difficulty at this point to warrant the longterm diagnosis.

ADHD is a diagnosis that is frequently given in early childhood but may not necessarily be reflective of what all of childhood or life is going to look like for that child or family. ADHD diagnoses in early childhood don't always stay ADHD. It may be that by age 10 or 12 that diagnosis is going to change or, in some circumstances, by age 10 or 12 that diagnosis is gone. At that point, it may be difficult to meet full criteria for a diagnosis. It's just like looking at a diagnosis of febrile seizures. That may be our story when we were little, but it isn't likely that it will remain the same over the duration of development.

Let's talk for a moment about the history of ADHD as a diagnosis. In the 1980s, what was then called the DSM-III, identified ADHD as two diagnoses. For tracking purposes, there was I, II, III, III-R, IV, IV-TR, and then V. So III, which was published in 1982, is three versions back. In 1982 there was an understanding that there were two different diagnoses, ADHD or ADD. Then in 1994, the DSM-IV revised it so that ADHD was a single diagnosis. However, the common vernacular is still, "I think it's only ADD, I don't think it's ADHD." When a formal diagnosis is given, it will always be ADHD, because the current classification is that there is only one diagnosis, not two. The presentations of those may look very different but the wording is specifically going to be the same.

Under the DSM-IV, and IV-TR, and V, ADHD is a single diagnosis with three subclassifications. Predominantly hyperactive, which was the old version of an ADHD diagnosis, predominantly inattentive, which was the old version of an ADD diagnosis, and combined type. All children with ADHD will exhibit some hyperactivity and some inattentiveness. The question is, is it generally both? Or is it more one than the other? We do see kids where the hyperactivity and impulsivity is very elevated, and then we see some kids who are what we frequently refer to as daydreamers. They're not really impulsive and they're not super hyperactive, but they really float away into their own thoughts and mind and headspace. Again, that breaks down a little bit differently in those subclassifications.

ADHD and Genetics

- ADHD is very genetic in nature.

- Children of parents with ADHD have a 50% likelihood of themselves developing ADHD.

- If both parents have ADHD, the likelihood increases to 75%.

- There are higher rates of ADHD in the US than in other countries.

- Potential reasons for this

- Rates of ADHD diagnosis have increased in the last 15 years.

- Reasons for this

Within that place of diagnosis, ADHD is very genetic in nature. Most diagnoses within the behavioral health world are genetic to some extent, but ADHD is really genetic. Children of parents with ADHD have a 50% likelihood of themselves developing ADHD. If you're the child of a parent with schizophrenia, the likelihood is that two generations from now, there will be a cousin who will then have schizophrenia, but there is not generally a linear line of individuals with schizophrenia or some other kind of psychotic disorder. With ADHD, if a child has ADHD, there's a 50% likelihood that one of the parents has ADHD. If both parents have ADHD, then the likelihood is 75% that that child will be diagnosed. That is a very genetic component. Sometimes, when we are looking at the assessment of is there is an ADHD diagnosis and what older adolescence might look like, we will begin to ask questions of parents. Mom, Dad, was this ever hard for you? Was this ever mentioned? Did you ever have assistance in school, any kind of accommodations, were you on medication? By asking these questions we're trying to delineate what the genetic factor may be, that this is the likely diagnosis.

There are higher reported rates of ADHD in the U.S. than in other countries. There's a possibility of a lot of reasons for that. It is not due to the U.S.'s emphasis on behavioral health services. Lots of countries do a much better job at decreasing stigma around mental health services and also ensuring families can access behavioral health services. We are not overreporting because we're overutilizing. We may be overreporting because the idea of saying, "This child is hyperactive" culturally feels better to us than saying, "This child is depressed." It may be a diagnosis that we associate with childhood and thus, feel more comfortable with. I have also heard psychiatrists say that in part, there is a higher rate of ADHD in the U.S. because of the way the U.S. came to be. If we just think about it from a strictly evolutionary standpoint, the idea that 500 years ago, some guy stood on a bank in England, and said, "I know what'll be fun. Let's put all of my family on a boat with no money and sail all the way across to see what happens." That feels slightly impulsive and maybe not well thought through. There are possibilities that there are higher genetic ratios of ADHD in the U.S. population just based on how people came to the U.S. to begin with.

We have seen that rates of ADHD diagnoses have increased in the last 15 years. Some of that has to do with the education of providers and that providers see what they look for. The more awareness that there is around ADHD, then that's what they're going to see. One of the other motivating factors that we have seen for an increase in ADHD diagnoses is the setup of school settings and how that moves with developmental expectations. It is not uncommon for the service area that I work in to have 3rd graders referred to my office. The teacher will send a note and say, "He can't sit through literature class. It's only two and a half hours. I don't understand why he can't do this." The attention span for a 3rd grader is about 12 minutes. That's what is developmentally appropriate, so a two and a half hour class is not. Now that's the expectation and that's what the system has set to be the norm, but because the system has set it as the norm does not mean that it developmentally is. We are seeing that some kids are winding up with ADHD diagnoses because that is helping them be adaptable to what the system has expected. We are seeing that with increases in family stress and with difficulties in finances, there also is an increase in difficulties with sleep hygiene. Sleep is a major issue in whether children have ADHD or are assumed to have ADHD. Insufficient sleep will create hyperactive behaviors, result in impulsive tendencies, and will also make children incredibly irritable. When children have had not enough sleep for weeks and months on end, then it's going to come out in certain ways. While we know that there's been an increase in the diagnosis of ADHD, that may have to do with lots of factors and may not actually be because there's an increased prevalence of ADHD.

Urban Legends

So back to those urban legends that I was talking about. In general, boys are more frequently diagnosed with ADHD. They tend to make up a larger portion of the population of diagnoses of ADHD, but the actual prevalence of ADHD among boys and girls is not as different as is reported. Boys typically are reported to have a ratio of ADHD of 2.3 to one, so a little more than two boys to every one girl diagnosed. The difference is that boys typically present as more hyperactive than girls. As a result, they warrant attention faster. Girls tend to be more inattentive in presentation and are generally much more daydreamers. As a result, they don't draw the same reactions. We generally don't get as concerned about the little girl who just colors for hours and maybe doesn't always listen super close as we do the boy who has now run in traffic three times. Boys tend to come to the attention of medical professionals sooner because of the severity of the behaviors and their hyperactivity and impulsivity are larger, not because they are somehow more predisposed to developing ADHD.

We do know that children diagnosed in later childhood (over the age of eight) generally have lesser symptoms and will always have lesser symptoms. These are kids who might have been diagnosed in 3rd grade. We do see diagnosis really pick up around 3rd grade, and that is because of a shift in curriculum. Kindergarten, 1st, and 2nd grades really are about the basics of learning how to read and learning basic math skills. There's still a fair amount of playtime involved. Then, when we get to 3rd grade, that shifts to this place of beginning to have textbooks, beginning to engage in longer projects, and having to be able to read to do math problems. The expectations become compounded and as a result, inattentive tendencies that we have had historically get brought to the forefront. For those kids that are diagnosed in 3rd grade and later, we see that those are also the children that, with some intervention and some coping skills, won't carry that diagnosis throughout life. They will be the ones, who at some point, no longer have enough difficulty to warrant an actual diagnosis.

Another urban legend to debunk is that individuals with ADHD don't actually have difficulty with attention. It's not so much about deficit of attention. Kids with ADHD often have bouts of what we call hyperfocus, where they will get into a thing, whatever that thing is, and can do that thing for hours. They may play LEGOs or video games or Minecraft or build a fort outside and spend hours doing that one thing. They get involved in something and stay with it for long periods of time. It's not so much that kids with ADHD can't pay attention. It is that that neurologically, they don't have the capacity to isolate different sources of input and prioritize where to put their attention. For many of us, we can drown out the background noise. For example, in this current moment, I can choose to be present here and can drown out the noise machine in the hallway or the guy down the hallway who just cleared his throat or if the telephone rings. However, if we struggle with ADHD, we hear all of it at a volume of 10 and can't really figure out where is the place that we're supposed to be. It's much more about executive function in the frontal cortex of the brain and about being able to prioritize and pick where to place attention and less about actual lack of attention.

Arriving at a Diagnosis

How do we get to diagnosis to begin with? Thinking about these 12 items that we have to have, plus B, C, D, and E, and knowing these components of genetics and what common thoughts are, there's a lot to think about and to understand.

The Process of Making a Diagnosis

- Assessing symptomology

- Confirming presentation of symptoms in two settings by a valid research tool

- NICHQs

- Connors

- APA Guidelines

- History of over diagnosis

The Team

Beyond getting the forms completed, a diagnosis should be made by a team. This team should include the healthcare provider in conjunction with parents, teachers, and the child themselves. Children are much better adept at giving words to things than we often give them credit for. I have had kids who will say things like, "I'm always busy and the other kids in my class can sit" or "I really wanna be on a good color today, 'cause I always get in trouble." They struggle from this place of knowing that something about them is somehow different, and not really understanding how to put that into words. Diagnoses are most reflective and are best made when they are in conjunction with everyone who is involved in the life of this child.

Is It Really ADHD?

The other part of the conversation when we're looking at diagnosis is the question, is it really ADHD? Again, ADHD is a diagnosis that we're really comfortable making in young children and it does tend to be the most common of diagnoses with young children. Again, this is mostly because it comes to our attention because we are having behavioral concerns. There is some form of behavior that has warranted an assessment and we're trying really hard to find some way of intervening and this feels like it fits.

All children, regardless of the motivation, exhibit strong emotions as behavior. If I am sad because my mom went to prison, if I am sad because my parents got a divorce, if I'm scared because somebody broke into our house, or if I have a personality conflict with another kid in the class and I can't regulate around it, all my strong emotions are going to come out as behavior.

Developmentally, children are most likely to engage in places of fight, flight or freeze. As a result, they manifest these survival skills by not focusing, being really hyperactive, or refusing to follow directions. There are so many overlapping symptoms you may see when looking at an ADHD diagnosis. ADHD in young children should be evaluated by a provider who's had specialized training in ADHD and who is very adept at evaluating it. This should be a provider who regularly diagnoses ADHD and who can rule out any other causes of the behaviors. This may be a longer process than we sometimes expect and might even take two to four visits.

If Not ADHD, Then What?

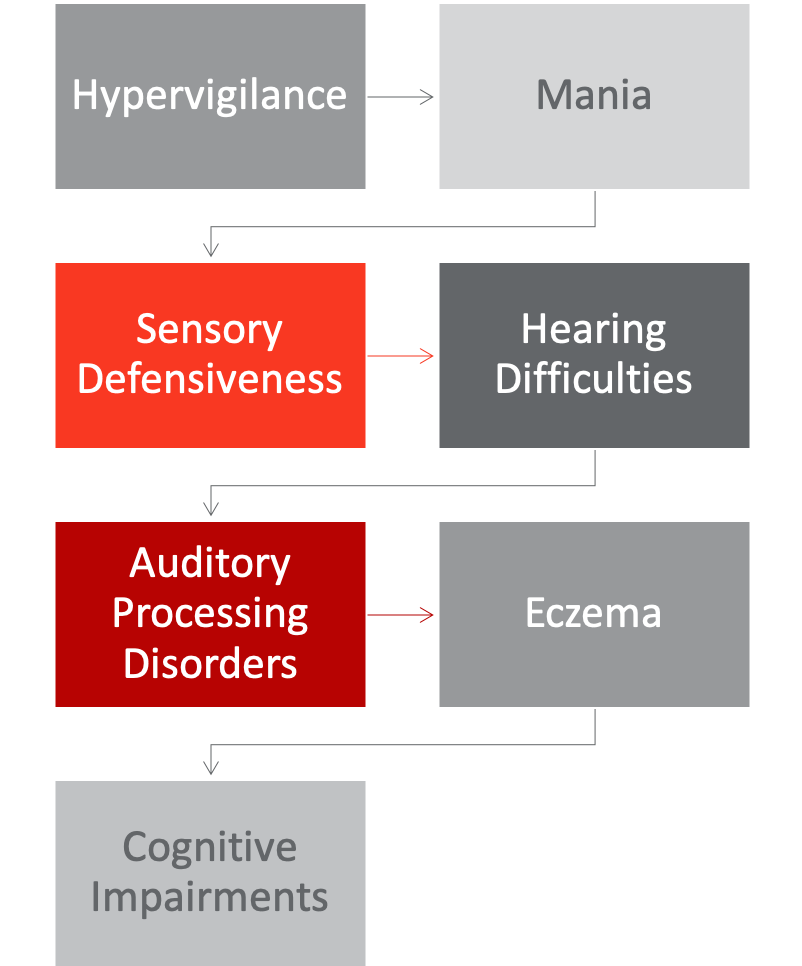

Figure 1. Additional diagnoses.

So if it's not ADHD, then what is it?

Hypervigilance

Sometimes, that piece of hyperactivity is what we call hypervigilance. I have had trauma and my world is scary. So now, I must always stay on alert so that I can prevent it from being scary again and I'm just going to constantly run at a 10. That is hypervigilance.

Mania

Sometimes, it's mania. Mania in young children is rare, but that doesn't mean it doesn't exist. Mania is very hyperactive and really impulsive. Again, it becomes this place of teasing it apart and how providers know to balance the qualitative nature of how those two things feel.

Sensory Defensiveness

There are lots of times that it is sensory defensiveness. These lights are too bright, these noises are too loud, these pants are too itchy. My mother used to tell the story about this old TV show from the 80s where a guy would wear corduroy pants, and he would say, they're whispering to me, because they would go swish, swish, swish, swish, swish. Those things bother a lot of people. If everything's too loud and everything's too bright and everything's swishing at me all the time, we tend to be a bit defensive and irritable and have a lot of difficulties paying attention.

Hearing Difficulties

Hearing difficulties will mimic ADHD quite a bit. If we are having a low-level hearing loss, then we're catching some of the big stuff, we're going to miss a lot of the little stuff, and we may not be as attuned to the input around us. As a result, there may be a lot of symptoms that look like ADHD.

Auditory Processing Disorders

Auditory processing disorders may also be the cause of some of these behaviors we've been talking about. Kids will take information in, but then their brain can't figure out what to do to send it back out, and so it all gets scrambled. I heard you, but I didn't hear you. I'm not really sure at this moment what you wanted from me, or what you said, or what the instructions were.

Eczema

Eczema is also a frequent one. For kids, especially with profound eczema and who really cannot get relief, there are times where medication just does not work for eczema. It's very painful and very itchy and very distracting, so those kids do tend to be much more irritable, much less focused, and much more hyperactive because they aren't comfortable.

Cognitive Impairments

The other big one that frequently happens is cognitive impairments. ADHD may be the first indication that there's an academic concern or a learning disability because those children are having struggles understanding what the instructions are or maintaining focus. This might not be because of ADHD, but because the material is too advanced for them. Working memory plays into this quite a bit. This means that I took the information in and now I can hang onto it and I know what to do with it the next time it gets recalled. If I can't recall that information, then that makes whatever's in front of me 10 times harder. It's back there, but I can't make it do anything. Those cognitive impairments and working memory impairments really do mimic some of that ADHD behavior.