This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Autism Basics, presented by Kimberly Norris, BS, MEd.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Name two diagnostic criteria of autism

- List three functional social communication skills

- Describe how autism affects development and learning

Autism Basics

In recent years, the incidence and prevalence of autism has been on the rise. You have likely encountered children with autism in your classrooms. As early childhood educators, there are some helpful facts about autism that we all should know.

First, let's look at what we would consider "typical" development. A baby is born. That baby grows into a toddler, and then into a child, and then becomes a teenager. Before you know it, that baby is an adult. That's how most people would view typical development. As educators, we know that there are more aspects to it than just the physical development.

Developmental Domains

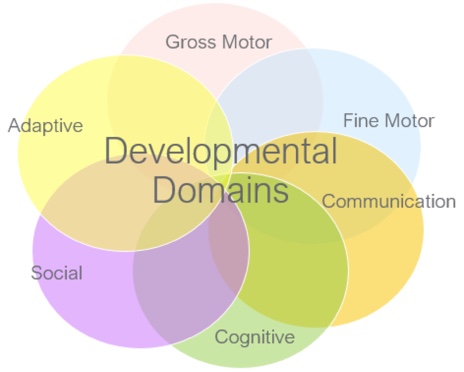

There are six different developmental domains: gross motor, fine motor, communication, cognitive, social and adaptive. As a person develops, these domains all overlap with one another (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Developmental domains.

Let's look at an example of a one-year-old child. At 12 months of age, a typically developing child is learning to climb and explore all sorts of things. The child's gross motor domain might be taking off at age one, whereas his communication might be lagging behind. That's because his little brain is wired for those gross motor skills right now. As he's climbing, he's learning how to use his gross motor abilities to get him where he wants to be, to explore his world a little bit more.

Similarly, a three-year-old might be learning how to role play, and enjoy dressing up as different characters. At this age, a three-year-old girl can probably run across the playground, and take care of some of her personal needs, such as dressing herself, toileting and feeding. Her gross motor skills are developing well, but her fine motor and social skills might be a little behind everything else. She can probably communicate with you by telling you about the outfit that she's decided to wear for western day. However, if you insist that her star-shaped sheriff's badge is not appropriate for everyday wear, she might not be socially advanced enough to be able to take that news with very much grace.

Developmental domains aren't necessarily always on the same level for every child. When we look at development through the lens of autism, we know that those domains are going to develop differently for children with autism than they will for typically developing children. Specifically, the domains of social development and communication are the hallmark areas of delay for children with autism.

What is Autism?

Autism is a neurodevelopmental disorder that can be broken down into three sub-components:

- Neuro: Having to do with the central nervous system, neurons, the brain, and how the person is "wired."

- Developmental: Indicators that appear as the child develops, not necessarily detected at birth.

- Disorder: This can be a somewhat of a controversial term, but because of the way that the diagnostic criteria are laid out for autism, we're going to go ahead and accept that it's not a typical part of development.

The diagnostic criteria are taken from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). There are two main parts to the diagnostic criteria for Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD). First, we know that these children have a persistent social communication deficit. The areas affected by this deficit include social-emotional reciprocity, nonverbal communication and relationships. Secondly, as outlined by the DSM, children with autism exhibit restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests and activities. This may include repetitive movements, activities and speech. The child may be rigid or inflexible. They may have restricted interests and they may show some differences in their sensory processing systems.

Diagnostic Criteria: Social

Social Communication

All communication is social, but some forms of communication are definitely more social than others. One of the main diagnostic criteria for autism is a persistent social communication deficit. What exactly is social communication? As an example, if you are getting together with some of your friends, you're going to communicate with them in a very different manner than you will if you're at a meeting with your staff. There are different types of sentences we use to communicate. Sometimes, we make statements of facts. Other times, we make small talk, like "How are you feeling?" or "How was work today?" Even within a statement of fact, there are bits of information that I'm forced to learn about you and your interests and then there are relevant pieces of information. I have to be able to sift through all of the information to know what is important to that communication.

What is communication? Communication is being able to transfer my thoughts and feelings about something to someone else. How do we communicate? We use both verbal and non-verbal communication. For example, I might comment to one of my coworkers the following statement: "That's a really nice dress you're wearing." I can speak that sentence with a smile on my face, using enthusiasm and sincerity, where I am truly paying them a compliment. Or, if I say it sarcastically in a monotone voice with a frown on my face, they may perceive it as an insult. Verbally, the words are the same, but depending on my nonverbal communication, the message is very different.

Functional Communication

Functional communication can be measured by the number of words a child uses on a regular basis, as well as if the child knows how to appropriately use those words in the right context. I can think of one example where a father brought his two-year-old son in for developmental testing. The dad very proudly announced that his son knew all the words to recite the Pledge of Allegiance. While it is impressive to hear a two-year-old pronounce the word "indivisible," strictly speaking, that is not considered functional communication. When we think about how that communication functions for the child, we need to think about if the child can label things, request items, ask questions or comment on different things. Functional communication allows the child to demonstrate to others his wants and needs in a way that we can understand.

Social-Emotional Reciprocity

Early learning is nearly always social. If you think about your own classroom, you want your young children to be involved with each other, and to be involved with you and your coworkers. They learn from each other as well as learning from you. However, when that social communication is broken, it makes it much harder for that child to advance in their skills.

Social-emotional reciprocity is the back and forth interaction that takes place in communication. We take a social approach in having conversations with others, and we share our interests in our conversations with others. Part of that social-emotional reciprocity is knowing how and when to initiate or respond to others' social interactions.

Some of the skills necessary to engage in social-emotional reciprocity include:

- Talking to someone

- Making eye contact

- Demonstrating something

- Using a chart or graph

- Writing a note, email, etc.

Let’s examine some foundational skills that underlie these methods of information sharing.

Joint attention. One of the basic skills involved in social-emotional reciprocity is joint attention. This typically develops in the first year or two of life. Joint attention is actively paying attention to the same object or activity at the same time with another person. We see babies do this all the time. As you're holding a baby, for an example, and he hears an airplane in the sky and sees you look up, he'll also look up to see what it is. He may point at the airplane and look back at you, wanting you to look back at that. This tends to be a skill that children with autism are missing. The lack of joint attention may be one of the early signs of autism.

Imitation. Imitation is another basic skill for social-emotional reciprocity. Parents, teachers and peers are all people that young children will imitate. Imitation is one of the ways that children learn. If children with autism have that break in that social-emotional reciprocity, if they have that break in that ability to imitate others, then their social communication is negatively impacted.

Reciprocal engagement. Once we have joint attention in place and we have imitation in place, then we usually enter into that reciprocal engagement. Again, it's the back and forth that we need to maintain long enough to learn something, to enjoy something and to share something with another person. It's paying attention to people versus paying attention to objects. Children with autism have a tendency to focus strongly on objects. Objects are much more predictable than people and much easier for them to understand because of the deficits in their social communication.

Non-verbal communication. Another area that can be affected in social communication is non-verbal communication. This would include facial expressions, as well as tone of voice. Using a single finger to point to an object is a non-verbal gesture that's important for young children to develop. You'll see very young children indicating what they want by pointing to it. They'll look at the object and then they'll look back at their caregiver to say, "Hey, pay attention to this. This is what I want. I'm pointing right at it." This often happens even before they can tell you the name of the object. Eye contact is a significant part of non-verbal communication, and is often something that children with autism will try to avoid. Maintaining eye contact with someone is very uncomfortable for them, mainly because of that gap in their social and communicative abilities. We need to teach them ways that they can use their gestures or behaviors so that they can communicate their wants, their needs and their interests.

Intelligence

Let's think about what it means to be smart. Is it simply the cognitive ability that we have? Are there different kinds of smarts? I think we can probably all agree that there are. Some people are much better at problem solving in the math world than they are in the literary world, for example. That doesn't mean that they're any less smart. It's just a different type of intelligence.

Some people have what we call street smarts, which would be functional intelligence that was gained outside of the school environment. Someone with street smarts is able to navigate the world using common sense and experience. This requires a high level of adaptive skills.

How do we show our smarts? In the education world, we use IQ tests. In the early childhood realm, we use developmental assessments. But let's think about what those tests look like. IQ tests involve lots of words. If a person has social communication deficits, how are they going to process all those words? Obviously, a person with autism spectrum disorder is not going to do as well on a traditional IQ test, because those tests are so verbally oriented.

The child with autism tends to have a higher degree of visual skills than verbal skills, because of the social communication deficits. As such, people with autism generally have a higher visual intelligence than they do verbal intelligence. That's why it's important to equip your classroom with pictures for your children with autism, because their visual-spatial intelligence will respond better to visual cues than to verbal cues.

ASD & Scatter Skills

Scatter skills are common with autism spectrum disorder. In other words, a person with autism may possess several skills within a certain range of developmental checklists, but may have two or three that are missing completely from that developmental range. For example, he may be very high in gross motor and fine motor skills, but his communication and social skills may be much lower.

To reiterate, children with autism will be more visual than verbal. In addition, we often see children with autism spectrum disorder displaying what we term hyperlexia. What that means is they may be three or four years old and able to sound out the words in a book. In other words, they're word calling. They may be able to open that book and start reading right away what those words on the page say, but we're not necessarily certain that their reading comprehension is equal to their ability to call out those words.

Long-term versus short-term memory also plays into this. In order to have a skill firmly established, you need to be able to have a good long-term as well as short-term memory. You have to store it in your short-term memory banks first and then, over time, it will enter into your long-term memory. That's an area where children with ASD also tend to struggle. Their short-term memory is not generally as well developed as their long-term memory. It may take many repeated instances of something being presented to them in order for them to learn that skill.

Remember that developmental delay is not the same as developmental arrest. When we think of being under arrest, we think of somebody being told to stop what they're doing. Then, when they are placed under arrest, those actions are going to remain stopped as long as that arrest is in place. That doesn't mean that a child who is in developmental delay is going to be stopped from further development. Children with autism can and do make progress in social skills. The vast majority will achieve joint attention, imitation, social reciprocity, etc. It’s always going to be an area of weakness, but they can learn these things. It’s just harder for them and takes a lot more work from the individual with autism, as well as their caregivers.

Social Deficits

Let's think functionally about social skills. Just how social does this child need to be? Well, he needs to be as social as his IQ would predict that he could be. Also, he needs to be as social is required in his world right now. Do we have to be as social in certain situations as we do in others? For instance, does he have to be as social in the grocery store as he needs to be in your preschool classroom? No. He's probably not going to run into as many peers, for example, in the grocery store. Furthermore, we don't necessarily want him to run up to everyone that he sees in the grocery store and to be as social with them as he would be with his peers in your classroom.

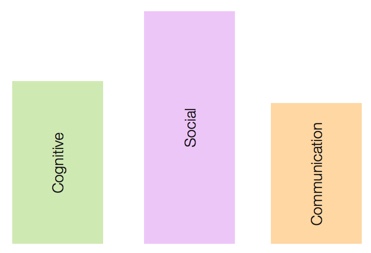

Exactly what do we mean by the term "social deficit?" Let's take a look at a simple bar graph. In Figure 2, the green column (far left) indicates the cognitive domain (IQ), or the child's capacity to learn. The purple (center) represents the level of social development and the gold column (far right) represents the level of communication development. If a child's cognitive and communication ability are lower, and his social ability the highest functioning of the three domains, would we say that this child has a social deficit? No, because his capability is lower than his ability. This may seem odd, but if you had a child with autism in your preschool classroom, some of their social behaviors probably don't match what their cognitive abilities would tell them they need to be doing. For example, a very social child with autism spectrum disorder may run up to a complete stranger on the street and try to greet them by saying, "Meow, meow, meow!" That's not at all appropriate to what a three or four-year-old child would typically be doing.

Figure 2. Example 1: Bar graph of developmental domains.

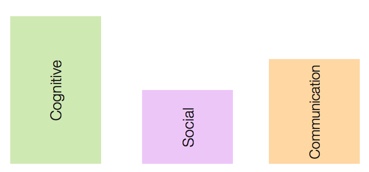

Let's look at another example (Figure 3). In this scenario, we have a child who has an IQ greater than her social or communication domains would indicate. Would we say that that child had a social deficit? Yes. We can see a big difference between her IQ and what her performance would be. This child would not only be unable to greet people appropriately, but would also be reluctant to do so.

Figure 3. Example 2: Bar graph of developmental domains.

I'd like to share one more example with you. We have a five-year-old boy who only talks about trains, has poor eye contact, and doesn't seem to understand other people's feelings. He has a high expectation of himself and of others, does not tolerate changes in routine, doesn't like to be touched and sometimes can get aggressive when he's frustrated. Would we say that that child has a social deficit? Yes. This child is probably getting ready to go to kindergarten. If he's only going to be talking about trains and not ever looking at anyone, he will not gain an understanding of the social world that he lives in. That's a prime example of what a social deficit could look like.

Shyness or ASD?

Let's revisit the diagnostic criteria. A child with autism will have persistent social communication deficits, which can impact the areas of social-emotional reciprocity, non-verbal communication and relationships. People will often ask me how to tell the difference between a shy child and a child with a social deficit. A social deficit will be pervasive across different areas of the child's life. The same social deficit exhibited at preschool is also going to appear in other environments, such as the home, at church, at the grocery store, and out in the community. It's going to show up across the board in this child's life. Conversely, a shy child, when with their loved ones, will reveal their social abilities a little bit better. By talking to the family about how that child engages with them at home, we can tell whether or not that social communication deficit is persistent, crossing over into different environments in that child's life.

To reiterate, social-emotional reciprocity is also affected by their functional communication. If I can't understand what that child wants or needs, then I can't respond to that child in a way that's nurturing and caring. Not to say that I don't respond in a nurturing way; but it's makes it harder when we don't truly understand what they want. These children become very upset when we don't understand what they're trying to communicate. The strain of misunderstanding can affect the relationships between the child and other people, such as peers or the caring adults in their lives.

Diagnostic Criteria: Behavioral

Next, we're going to take a closer look at the second main area of the diagnostic criteria, which is the restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests or activities. First, we're going to examine the repetitive movements, activities or speech that may be involved in this child's behavior. We're also going to discuss the tendency of those with autism to be very rigid or inflexible. Finally, we will define what restricted interests means, and we'll outline some sensory processing differences.

Repetitive Movements/Speech

The fidget spinner was one of the hottest stocking stuffers last Christmas. Now, while that is an object that is intended to be spun, children with autism spectrum disorders will find many different ways to indulge in that spinning of objects. I've seen children turn toy trucks upside down so that they could spin the wheels. I've also seen them take the lids of canning jars and spin those. Plastic dishes spin really well, believe it or not. It's not just restricted to spinning objects. Sometimes children with ASD will spin their own bodies or parts of their bodies. They'll spin their hand or their fingers, just so that they can have that fulfillment of spinning.

Sometimes, children with ASD will run, jump and crash into other people or into heavy objects, so that they get that heavy input into their bodies. We'll talk a little bit more about that with the sensory processing differences, but that may be something that they will repeat over and over again for that input. Some children with ASD may say or sing a phrase repeatedly, like a commercial jingle that they've heard before and that they find comforting. They also may fixate on a particular phrase or a set of rhyming words and say it over and over.

Rigidity or Inflexibility

Another characteristic of children with autism is that they tend to be very rigid or inflexible. These children are going to insist that they do the same thing every single day, the same way, at the same time, in the same manner, in the same order. They would probably be perfectly content to wear the same thing every day. For these children, variation from routine can precipitate a meltdown and we definitely don't want to see that happen. Routines in the classroom are actually sources of comfort for these children. They may not enjoy tooth brushing, and dislike the sensory aspects related with brushing their teeth. However, if you can find that routine, some sameness in that routine to bring to their life, that can be a big help to them. You may find that these children have such an insistence on sameness that they become ritualized. In other words, they may feel like they have to do the same thing in a routine several times and it may be somewhat of a ritual to them, but that's also very comforting and brings a definite feeling of calm to them.

Restricted Interests

Restricted interests are common in children with autism. Think back to our example of the child who only talked about trains. For some reason, children with autism are fascinated with mechanical objects, such as trains, airplanes and elevators. I hypothesize that it's because these machines work in a predictable manner. As such, these objects tend to be desirable to these young children. You may find a young child who is four years old, but can talk at length about aircraft that were popular during World War II which is an odd interest for a four-year-old. If they have that restricted interest, that's all they want to learn about. We need to figure out a way to capture their interest, and bring in activities to our classrooms that relate to those interests, so that hopefully we can draw them in to a social interaction.

These children may often carry a particular object with them constantly which brings them comfort. Because they are so busy holding on to their object, they may not even recognize that they are limiting their own ability to interact with the other things in the classroom. I would not recommend trying to take the object away from them, as it brings them a sense of calm. Try to find out why that particular object brings them that level of comfort and see if you can use it in the classroom to expand their learning, thereby expanding their world.

Sensory Processing Differences

Some sensory processing differences that exist in children with autism include:

- Hypersensitivity

- Hyposensitivity

- Unusual interest in sensory input

Hypersensitive. The hypersensitive child reacts strongly to sensory processing input, which could include textures, sounds, visual input, temperature and the lighting. They may react to the way we have the furniture arranged, or to pictures that we have hung on the wall in our classroom, or the fact that it's too hot or too cold. We may not have control over the temperature or the lighting in our room, but we may be able to adjust other things that they react to. We need to be aware of how those sensory processing differences are going to affect our students with autism.

Hyposensitive. The hyposensitive child is under-reactive to these sensory processing inputs. They may not respond to you calling their name, or to the visual input that's around your room. They may not be affected by textures like other children are affected by textures. For example, children who are hypersensitive may be completely unwilling to engage with specific textures, like Play-Doh or paint. Children who are hyposensitive have a lower than normal response to these sensory processing stimuli.

Arousal States

There are particular states of arousal, ranging from high to low. Children with high levels of arousal may be jumping up and down all day long, screaming and yelling and engaging in behaviors that aren't safe. These are the children who get into trouble and require a lot of attention. On the other end of the spectrum, children with a low arousal state are quiet and sit in the corner, not bothering anyone. These children are often overlooked because they aren't causing trouble. However, in this low arousal state, they are not engaging, and therefore are not receiving the appropriate level of learning. When the state of arousal is either too high or too low, it falls outside the optimal level for learning.

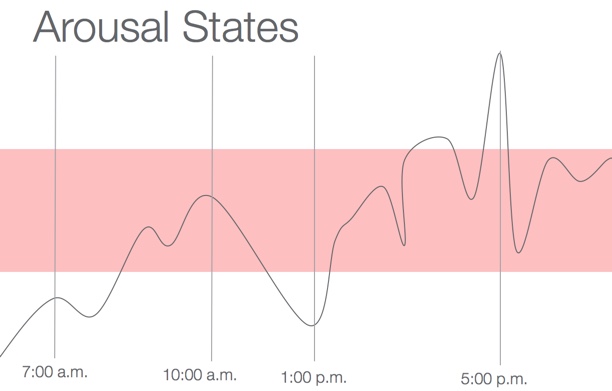

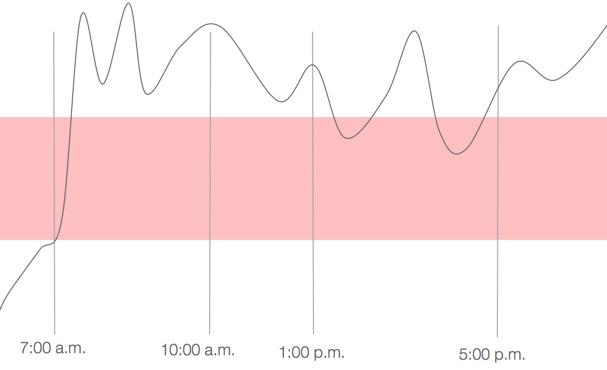

Let's look at an example of how arousal states change throughout the day (Figure 4). This pink area indicates the optimal level of arousal where is person is ready to learn. The black line indicates arousal levels at certain times of day. Before 7:00 a.m., my arousal level is very low, and comes up at 7:00 a.m. You could probably safely assume I've just woken up. It may take me a little while to get started, but eventually, I come on up into that optimal level of arousal. If I'm a preschooler, hopefully I'm going to get to that optimal level sooner rather than later in my classroom so that I'm ready to learn. During the day, I experienced a little bit of fatigue at around 9:00 a.m. Maybe I ran too hard on the playground and got tired and just needed to take a little break. I rested a bit and my arousal level came back up again, remaining in this optimal zone. At 10:00 a.m., I was right in the middle of that optimal zone of arousal. Notice that my arousal started to drop down and by 1:00 p.m., I was under aroused again, at a similar level to what I was just prior to 7:00 a.m. That's probably because it's nap time at my preschool. If I'm asleep, it makes sense that I'm going to be under aroused. Once nap time is over, I come right back on up into that optimal arousal state. For the most part, I'm staying strictly within that optimal level of arousal. I am ready to learn, I am doing great and then all of a sudden, at 5:00, my arousal level spiked. Can you imagine why that might be? I'm thinking that I became excited that my mom came to pick me up from school. Then we go home and I'm engaging with my family and going through my evening at that optimal level.

Figure 4. Arousal states throughout the day.

Now, let's look at another example (Figure 5). This child wakes up at seven a.m. and her arousal state shoots way up above that optimal level and remains high all day long. She barely ever dips down into that optimal level where she's able to learn to her best ability. This child may be overly stimulated by the things that we have going on in the room, such as the lighting or the noise level. This overstimulation is going to affect the not only the child's ability to learn, but also make things harder for everyone, including me, my teacher and other children around me.

Figure 5. Arousal states in a child with autism.

Behavior is the observable evidence of a person's skillset. A prime analogy that we can use is the proverbial iceberg. What do we know about icebergs? Only the tip really shows. The majority of the iceberg is under the water. Similarly, we can’t “see” someone’s skills, or developmental level -- those are below the surface of the water. We see the behavior that they’re exhibiting. We see them putting those skills to use, or the tip of the iceberg. We can’t “see” that a child can add. We can see that they look at a math problem and write the correct answer. It’s important to realize that the behavior is the external manifestation of the skills. When a child is behaving a certain way, another way to think of it is that they’re using (or not using) certain skills.

Behavior and Development: The Hot Spots

When it comes to behavior and developmental skillsets, there are certain times of day where we're going to encounter challenges in our routines that are going to cause some problems. Let's talk a little bit about some of these "hot spots" in your classroom.

Transitions

In order for a child to successfully handle transitions in the preschool classroom, they need object permanence. They need to understand that even though we need to put the bubbles or the toys away right now, they are still going to be here when I come back. They need to understand a sense of time. They need to have sensory processing that works in their favor. They need to have a specific attention span so that they can understand the directions that you're giving them for the next activity, but we'll be able to come back to that preferred activity in a little while. They need to possess the self-regulation to be able to say to themselves, "It's okay. I can handle this. I understand that these bubbles will still be here when I come back and we're just going to do something else right now and that's okay." Children need to be able to do all of those things in order to successfully transition.

If any of these skills are missing, then that child is going to have a problem with transitioning. Knowing what we know about autism, it's no surprise that a child with ASD may have some trouble with transitions. As ECE professionals, we can give them some tools to help them through that transition time. For example, if a child has problems with sensory processing, then maybe we could give them some sort of item that they could carry through the transition that would be a comforting texture to them. Or, if the lighting continues to be a problem for them through a transition, we may be able to dim the lights or give them some way to shade their eyes to provide them that tool they need to get through that transition.

Compliance

In order for children to comply with directions that are given to them, they need to have appropriate receptive language. In addition, they need to be able to pay joint attention to people as well as to objects. They also need to have short-term memory in place, as well as to understand cause and effect. They need to be able to know that if they follow the teacher's directions, they will safely get to where they need to be and they will have a good time doing the group activity. We need to be aware of our children's receptive language level, because if we're giving them instructions that are way above what they can understand, they will have meltdowns. If they can't pay attention to what we are saying, as well as to the activity that we're asking them to engage in, it's not likely that they're going to comply with us. Therefore, we need to be aware of each child's abilities and skillsets in order to make sure that our instructions match their skillset.

Classroom Participation

Classroom participation tends to be a hot spot because it's a social and communicative activity. All of these different skills that we have been discussing are involved with classroom participation:

- Receptive language

- Joint attention

- Short-term memory

- Cause and effect

- Reciprocal engagement with peers

- Sensory processing

- Sense of time

If these skills are not in place, then we will see trouble with classroom participation. Being aware of that child's skillset can help you gauge whether they're going to be capable of being involved. For example, in a circle time, a child with autism might only be able to sit still for one minute. We might have to adjust our expectations for the child with autism spectrum disorder in order to increase their level of classroom participation.

Self-Regulation

In order to have good self-regulation to remain at that optimal level of arousal so we can learn, we must be able to exert control over our emotions, thoughts and behavior. Children with autism spectrum disorder often feel like they don't have control over these things; as such, those repetitive motions are important coping mechanisms for them, because those are things that they do have control over. They can control how fast that wheel is spinning or how hard they're crashing their own body into another object. Those actions can help bring a child with ASD into self-regulation. By exercising control over that repetitive motion, they can understand their level of control over their own emotions, thoughts and behavior.

Summary and Conclusion

In summary, remember that an autism diagnosis is a medical diagnosis. As an early childhood professional, you may be asked to provide information to assist with an autism diagnosis by listing some of the behaviors and skills that you've observed in the classroom. It's important to understand that it's not our job, as an early childhood professional, to provide a parent with suspected diagnoses of autism. That's not what we need to be telling families. We need to be telling families that their child has exhibited this behavior or this skill and if you have concerns, please encourage the family to see their child's doctor. We are not equipped to give a medical diagnosis in the early childhood classroom. We do, however, need to be able to describe typical behaviors for that child and typical skills that that child has demonstrated to any substitute, floater, or new teacher that might come into your room. Knowing those things can help a new teacher to adapt your classroom when they have to be left in charge of those children. Otherwise, you may have a child who becomes very upset when those new people enter into your room. Remember that changing your classroom arrangement can also cause behaviors to emerge, because that change can affect that child's comfort with that level of sameness that they crave. Be aware of those things as you're setting up your early childhood classroom. The more that you can leave the same and the fewer changes that you can make for that child, the better.

Citation

Norris, K. (2018). Autism Basics. continued.com - Early Childhood Education, Article 22874. Retrieved from www.continued.com/early-childhood-education.