Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Catch a Bubble, Finger on the Wall, Are We Teaching Them Anything at All?, presented by Jennifer Romanoff, MA.

Learning Outcomes and Introduction

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Describe the expectations teachers have of children in an effort to control behavior.

- Describe the actual lessons presented to children when unrealistic expectations are set.

- Explain the true objectives of daily activities as a way to foster valuable life lessons.

This session is going to focus on the life lessons that we are teaching the children in our care. Life lessons are just as important as all of the developmental milestones and key indicators of all the development children are going through. We really need to remember that we're not only looking at making sure they reach those but that we're also creating good people. These children are going to take over and eventually one day take care of us, so we want to make sure that they have every opportunity for success and development on a multitude of levels.

The first thing I want to cover is the learning outcomes. We want you to be able to describe the expectations teachers have of children in an effort to control behavior. A lot of times we hear that there are behavioral issues, but during this course, I'm going to ask you, are you expecting a little too much, or are you expecting children to do things that we as adults don't do? Are we setting them up to behave in a certain way? We're going to talk about that. Another learning outcome is to describe the actual lessons presented to children when unrealistic expectations are set. That relates to what I just said, but how do we alter our lessons to ensure that we are not setting them up and we are not having unrealistic expectations? We are going to talk about the actual lesson plans. The last learning outcome is to talk about the true objectives of daily activities as a way to foster those life lessons. As I said, we always focus on those developmental milestones for children whether it be cognitive, physical, social-emotional, or language development, but there's also a whole other set of lessons that need to be taught to children. Those are valuable life lessons.

Pause and Reflect

Take a moment to pause and reflect. Think about all the children in your care and think about the time that you have with them, whether that's year-round or just for the school year. There are valuable lessons that you want them to learn. What would be one or two major things that you would want the children to learn before they left you?

I've done this exercise before and I have actually reflected on these things myself. I am sure that some of you are thinking about things such as:

- I want them to get along with others.

- I want them to understand how to take turns.

- I want them to be kind.

- I want them to have empathy.

Those are all great things and are the things that I hear a lot when teachers are asked the question, what are the lessons you want to really teach children?

Thinking about those things and the examples that I just gave you, my next question is, are those in your developmental milestones? Are those in your scope and sequence of skills that you have to teach according to the curriculum that you have in your center? You're probably shaking your head no. The reason for that is that those are the life lessons that I've been referring to in the first part of this course.

The Magic Question

The magic question I am going to pose to you is, "What's the objective?" When you look at your daily schedule and at all of the great activities that you have planned for the children, take a step back and ask yourself, what's the objective? When I say what's the objective, I want you to think about what is the ultimate goal, but the minimal amount of goals that you want the objectives to be for certain parts of time in your daily schedule. Your daily schedule is broken down into a lot of different areas including whole group, small group, table time, time outside, transitions, and rest. Think about what is the true objective of each one of those times. What is the ultimate goal that you want children to achieve? How do you want them to behave during that moment?

Your Daily Schedule

- Circle/Group Time

- Snack

- Small Group Interactions

- Music & Movement

- Story/Flannel Board Fingerplay

- Lunch

- Rest Time

- Outdoor Experiences

- Transitions

Circle/Group Time

Let's talk about your daily schedule, starting with circle and group time. Think about what the objectives are behind coming to circle or group time. What do you think those objectives are? Some of you may be thinking that it is to teach the calendar, to take attendance, or to introduce the theme. Now I'm going to ask you to change your paradigm and change your way of thinking. Those are all great objectives and what you need to meet in order to give the children the skills that they need academically and socially to move on. However, I want you to think of your objectives of circle time as very easy things to do. Objectives such as to come together as a group and to do that with minimal friction. That's it. If those are what your objectives of circle time are, don't you think the children would succeed a lot more in that timeframe?

Again, wash out the way you're thinking of circle time and wash out those things that you want children to learn. The objective isn't the calendar, taking attendance, reviewing the days of the week, or changing the clothes on your weather bear. If your mindset was set to think that your objective for circle time was to come together as a group with minimal friction and you don't want anybody hitting each other, then those children that aren't sitting crisscross applesauce probably wouldn't get in trouble. Those children that need to stand because they're more bodily-kinesthetic children would probably be more engaged if you weren't taking them out of their comfort zone because they need to stand, they need to release those endorphins, and maybe during your welcome song they need to jump up and down.

That goes back to the learning outcome of setting expectations. If we expect that children are going to sit crisscross applesauce for 15 minutes, not move, not touch one another, and not need to do something with their little kinesthetic bodies, then we are setting them up to ultimately fail us and to get in trouble. Wouldn't it be better if you brought everyone to your group time and they didn't have to sit in a circle or on little rubber circles or pieces of fabric and could sit any way they want, even if they wanted to stand or sit on their knees? Your objective is to come together as a group with minimal friction. If you allow children to have flexibility in the way they join a group, then you're going to be able to sing the welcome song, go through the calendar, change the weather bear's clothes, talk about the days of the week, go through the alphabet and the numbers and the counting, and introduce your theme without having to say things such as:

- Johnny, crisscross applesauce, come on, crisscross applesauce.

- Come on, you know how to sit.

- Don't touch each other.

- Can you stop bouncing around?

- Sally come back to the circle.

If you just let them be and realize that your objective was to come together as a whole group, not putting those very specific parameters on the way everybody needs to sit, then your expectations are going to be more developmentally appropriate for the children.

I'm going to bet that right now, some of you are sitting with your legs crossed and some of you are sitting with both feet on the floor. Some of you might be sitting with your head propped on your hand because it's a relaxing time for you and you're gaining all of this information the way that's most comfortable to your body. Some of you may be feverishly taking notes. Some of you may just be listening because you're more auditory learners. I guarantee you that everybody out there right now is sitting in a different fashion to grasp this knowledge because it's how you are most comfortable. You've put yourself in that position to be able to open your mind to the information that's being served. So why wouldn't we do that to children?

That's the magic question, what's the objective? It's not the developmental milestones. Those will come naturally when you allow children to be in their most comfortable state when you're giving that knowledge. This may be a little bit of a wow moment and some of you might have light bulbs going off. Now that I have given you a pretty solid example of the objective behind circle time or group time, let's go through the rest of your daily schedule. Remember, that objective was to come together as a whole group with minimal friction because you don't want any conflict happening and you want everybody to keep their hands to themselves. That's a life lesson that we're learning.

If you're watching this right now with a colleague, I'm sure you're not poking them with your pencil or hitting them with your water bottle or making that connection that's a little bit more physical because you're being allowed to sit the way you want to sit. Now that your mindset has shifted and your paradigm might be seeing things a little bit differently, let's go to the next part of your day and see if we can come up with those "What's the objective?" objectives.

Snack

The next time on our schedule is snack time. Think about the things that I talked about in group time. What is your objective behind snack time? It might be to sit at a table and to independently eat, depending on the age of the child or the children that you have in your classroom. That might be your only objective. For the older children, maybe it's to clean up after themselves. Again, don't just think of the developmental milestones or the academic skills that you have listed in your curriculum, think more about life lessons. When you come together at a table it's a different environment than in group or circle time where we're all sitting on the floor or having a picnic outside on the playground. It is sitting at a table, not falling out of a chair, and not eating the snack that belongs to the person next to you. The objective is to come to the table, to independently eat, and to maybe clean up after one another. If you reset your mind to think of the simplest life lessons that are the objectives behind the times during the day, you probably will lower your frustrations a lot more and set the children up for success.

Small Group Interactions

The next thing on our schedule is small group interactions. What do you think the objective behind that would be? You might say that it's to play, to be part of a group, and to interact. It's okay if there are three or four children. If space allows, it might even be okay that there are five or six children in a learning area. Instead of having learning areas where you put up cards and only allow three people in at a time, think of all of the learning that can happen if there are four or five children. As long as you are in that area and you are not watching and observing and talking at, but you're engaged and interacting and talking to, it's okay.

Sometimes we have those moments where we're so ecstatic about building blocks that all the toddlers want to come over and we stop them and say, "Oops, nope, only four can be in this center." It's okay, as long as the small group interactions are working and everybody's under control. If you're telling children they can't go play with that one thing that is so attractive them and they can't come play with you while you're using silly voices and having a great time, then you may be setting them up to have a temper tantrum. Just let them play. What's the objective? To play in smaller groups rather than as a large group and to interact with one another.

Music & Movement

Music and movement are next on our schedule. Let's enjoy the music and let's enjoy the movement. That's it. It is okay if they want to spin and it is okay if some children need a little bit more room than others. Music and movement is a time of the day where they're really starting to understand their body and control, so it is okay if you give them a little bit more space and you're not on your circle time rug. It's okay if some children go over there as long as they're in a space that's safe and they're not going to hurt themselves on anything. It's okay if somebody wants to sit and just bounce up and down.

Think about your objective. Are they still listening to music? Are they still potentially bouncing or clapping and understanding rhythm and tempo? Are they still releasing endorphins? Yes, they absolutely are doing all of these things. They just might be doing them in a more confined space where other children need a little bit more space to spin and bounce and flail. It's okay because they are releasing endorphins, they are enjoying the music the way their body enjoys the music, and then when their brain naturally makes those synapses connections, it's okay to not keep them so confined. When you do that, that's exactly when you're setting them up to let you down. They need that space. Think about what's the objective. It's those minimal amounts of things that we really want children to learn and understand, and all of those other developmental skills will just happen.

Story/Flannel Board Fingerplay

Think of story and flannel board time like group time or circle time. It's okay to stand, lay down, or sit with your feet extended as long as you're not kicking or bothering anybody else. The objective is to enjoy the story as you come together as a group and enjoy verbal imagination. It's not to sit, to understand left to right progression, or to understand that this page comes after that page. Those things naturally happen when you allow them to sit the way they want to sit. That's when they're going to watch you. You are the role model. They will see that the pages get flipped from left to right and see that natural progression. They will start to anticipate what's coming next. When you allow them to just be, you're allowing them to be successful in that space.

Lunch

Lunchtime is very reflective of snack time. Again, your objective might be for them to come to the table, to eat their own food, to eat independently, and maybe again, with the older children, it's to clean up. Those are the minimal things. It's not to sit, don't speak, or don't talk with your mouth full. When you have that environment set for success, you'll see that all of those other things just come into play.

Rest Time

Rest time. What's the objective? To rest. Could they be wiggly? Could they have a toy? Could it take a little bit longer for them to finally settle their body? Yes, absolutely to all of those questions. Rest time is just simply to rest. It's not to lay on your cot with your blanket without movement. There may be some whispers. I know some of you teachers are thinking, "Oh my gosh, we can't do that. One is going to wake up another, who's going to wake up another, who's going to wake up another." You're right, that's going to happen. What you can do is take those children who need less sleep and have a little bit more ants in their pants and move them to an area of the room where you can be a little bit more interactive with them. Move the children you know are going to adamantly fall asleep each day to the back so that they have that more quiet time. Remember, different children need different levels and different hours of rest.

Outdoor Experiences

The objective for outdoor experiences is to be outdoors, to get Vitamin D from the sun, and to learn in a natural environment. That's all it is. It isn't necessarily to get on a bike for large motor or climb the unit so that you can make sure they're doing left-right foot. It's not about those things. It's all about just getting outside.

Transitions

The last thing on the schedule is transitions. I'm going to use the example of the transition from your classroom to the playground. What is the objective behind that? The objective is to get from point A to point B with all your children. That's it. It's okay if they hold hands. It's okay if they walk independently. It's okay if they walk in the hallway next to one another. We will talk more about that in a few minutes. I want you to remember this example of moving from the classroom to your outdoor learning environment.

Think about the question, "What's the objective?" the next time you are creating lesson plans or the next time you are expecting children to behave in a certain way or sit in a certain way or for a certain period of time. If you find that when you are expecting these things children are having behavioral issues or they're not sitting for as long or staying there as long as you expected them to be, it's not necessarily because of the children. It may be because your objective isn't necessarily meeting the way children learn. That really is the crux of developmentally appropriate practice. It's not making children all learn in one way, it's teaching children to learn and meeting them where they are. It's not expecting them to meet us where we are.

Do you do this?

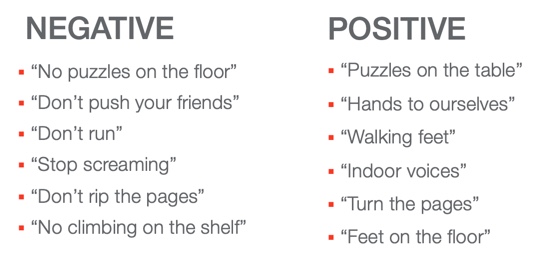

Figure 1. Do you do this?

As we move on, I want you to keep the magic question (what's the objective?) in the back of your head. As adults, do you do these activities? When you walk from your classroom to the bathroom or from your classroom to your staff kitchen, or in a shopping area, do you "catch a bubble" or "put a quiet finger on"? Do you do this when you're walking in the hall? I've seen children have one finger at their lips and make a peace sign with their other hand, which stands for peace and quiet. If you don't do these things, then why are you asking children to do them?

When your children move from one area of your school or your center to another, do you ask them to walk with their finger on the wall? I know some of you do and some of you even have songs. ♪ Put your finger on the wall, on the wall ♪ ♪ Put your finger on the wall, on the wall ♪ ♪ Put your finger on the wall ♪ ♪ When you're walking in the hall ♪ ♪ Put your finger on the wall, on the wall. ♪ Are you walking through Kohl's, Target, a strip mall, or a larger indoor mall like that? Do you do this when you go out with your friends or your loved ones to the mall? Do you put your hands on each other's shoulders and chugga chugga chugga through? If you don't do that, we probably shouldn't be asking children to do that. It's not a life skill that they're going to continue on with.

Think about when you're walking on the sidewalk. What happens when somebody is coming in the opposite direction? You move over, smile, say hi, and engage with someone. That's all about the human connection. When you're walking in the hall with the children, it's okay to have them walk alone, with a friend, in a trio, in a group, with you, in front of you, or behind you. It's okay to talk and point out all the wonderful things that you see on the bulletin boards. Look at all the colors and if you have those vision panels or windows from the hallway to the classroom, look in a classroom and see what's going on. If you're walking past the baby room tell the children, "Okay friends, some of our babies are sleeping so let's use our whisper voices when we walk past this room."

Do you see the life lessons that you're teaching them? The objective is to get from your classroom to the outside with all your children. If you can teach them some life lessons while you're doing it, kudos to you. What happens when another class is coming in the opposite direction because they're leaving the playground? That's really easy. Just say, "Okay friends, our other class is coming in so let's all move to the side so we can share the hallway and when they're passing, let's say good morning. Let's ask them how the weather was outside and if they had fun." Those are all the life lessons that we want to teach children. Again, what's the objective and are these things that you do as adults?

How about when milk gets spilled? A lot of times I've witnessed accidents happening in classrooms where teachers say, "Okay, everybody back up. Back up. No, no, no, don't touch it. Just go over there." Then they run to the sink and get paper towels and go clean it up. Now the child who has accidentally spilled their milk is kind of in a state of shock. They don't know what they've done because it clearly was an accident. All the other children are just ostracized away thinking, "Oh my gosh, what just happened? There's milk on the table." My question to you is, what can be an objective behind it? One, it was an accident. It's not called an on-purpose, it's called an accident. Instead of just shooing everybody away, how about we say, "Oh baby, it's okay. It's just spilled milk. Let's go get some paper towels together and we can clean it up. Friends, let's not touch that milk until we clean it up. If anybody wants to come help us, I can get you a paper towel, too." That's a life lesson. That's an objective. That's thinking about things differently and wondering, where is the moment and the opportunity to teach a child something they're going to need for the rest of their life in this moment? The next time somebody spills milk, you may see children just going and getting paper towels themselves. You've taught them that. You've taught them to be independent and to really understand what it's like to help one another and help themselves. If you spill a cup of milk or water or anything when you're at home, if you don't react in a way that's, "Oh my gosh, everybody back up," then try not to have that reaction for the children in your care.

Last I want to talk about circle time and the way you're all sitting right now. I am not expecting you all to sit the same way. I am not expecting you to all be in the same type of seat. I'm not asking you to all sit on the floor and sit with your legs in a certain position. Sometimes it's just not comfortable for people to sit a certain way. If you go to a seminar, concert, or a movie theater, if you're not all expecting to sit in the same exact fashion then don't expect children to do that as well. Again I'll ask, what's the objective and what's the life lesson? Those are two questions that you always need to keep in the back of your head.

If it's not broke...

Now the age-old quote of if it's not broke _____. I know you said it. Don't fix it. Here is my challenge to you. You have certain children in your room that love to go to the same center all the time. The reason they do this is because of their natural aptitudes for learning. That's actually called The Theory of Multiple Intelligences and was created by a gentleman named Howard Gardner. He did some studies on the way people learn and he found that everyone learns best in certain ways. Some people are visual and some people are linguistic, meaning they like to read things. Some people are more mathematical learners, some are musical learners, and some are kinesthetic where they need to do it as opposed to being shown or told what to do. They need to actually do it. Some children are more natural learners. There are a bunch of different ways that you can receive knowledge.

Children will naturally gravitate to the centers where they grasp knowledge best. That's why it's so important for you to have theme integration throughout if you work on thematic-based units. Let's just say Sally loves to go to dramatic play. That's likely the area where she learns best. She learns best through sharing, taking care of dolls, interactive play and role modeling the things that she sees in her home, church, community, or maybe even in your center. Let's say Johnny is more of a mathematical learner, so he is going to gravitate towards blocks, construction, and trucks.

I know you all have the best of intentions and you want the children to get the best of what your program has to offer and all of the great areas of your classroom. However, you know if you ask Sally to leave dramatic play, she's going to throw herself on the floor and have a tantrum. You know if you ask Johnny to leave blocks, he is going to start throwing them and swinging. Rather than force children to go to different learning areas, let them stay in the one where they are more likely to learn. If it's not broke, don't fix it. It's okay, they're going to learn more in the centers that are more attractive to them with their natural aptitudes than they will learn from the centers that you force them into because that's not necessarily the way their brain is connected and works. Let them play and do exactly what they need to do. They don't realize it and maybe you haven't realized it until this moment that they're attracted to the way they gain knowledge. If it's not broke, don't fix it.

Language Development

Now we're going to talk about language development and the way we speak to children because that really does have an impact. What they hear is what they're going to repeat. The first three words in the English language that most children learn are da, ma, and no. That says a lot about the way we speak to children. Remember, the first 12 months of a child's language development is all auditory. It's all auditory because we're waiting for palate development to take place and the ability to then control muscles and have everything come together so they can spit it back out in verbal form to you. This is what we're hearing, these are the trends, and that's because this is what we're saying. That first year of auditory, these are the words that they hear the most.

I'm going to talk to you about the way your brain works. If I say to you right now, "Don't think of a pink elephant," I'm going to bet you the first thing that came to your mind was a pink elephant. The reason for that is because your brain is naturally programmed to go to the action word. Not the negative but the action word. The action word in that statement was "think." Your brain automatically thought, "Think. Okay, think of what? Think of a pink elephant." It didn't matter what happened before that sentence, your brain went to the verb or the action word.

Let's say you're a toddler teacher and you have a child who's biting. When Sally gets dropped off and her mom or dad want her to have a good day they might say, "I love you so much, Sally. Don't bite your friends today." instantly, Sally's brain goes to, "Bite your friends today." Not, "Don't bite your friends." It goes to the action word, "Bite." Then Sally starts recalling everything that happened when she bit her friends. Maybe she had some one-on-one time with the teacher or maybe she got put at a table with her favorite book. That's a whole different learning objective about positive and negative reinforcement. The whole objective behind this information is for you to understand the way a brain works. Brains go to action words and verbs first. A lot of times, we put those in the negative things we say.

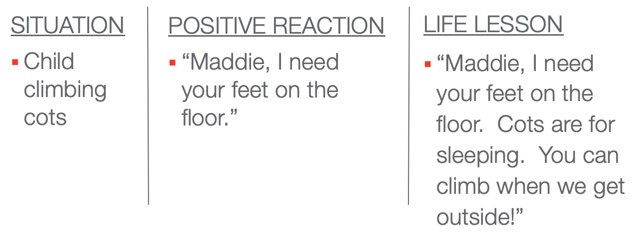

Figure 2. The way we speak.

Let's look at the list in figure 2 one by one and create a positive statement based on the negative statement. The first one is, No puzzles on the floor. Instantly, we say, "No puzzles on the floor," and their brain goes to the action. They think, "Puzzles are on the floor because I can take it out of the shelving unit or its container and I can put it on the floor." Instead, we should say, "Puzzles on the table." This way their brain naturally goes to the action which is the movement of puzzles on the table.

The next one is, Don't push your friends. What does the brain think? Push your friends. If we said it in a more positive way, we would say, "Hands to ourselves." It's something that the brain can visualize even at a very young age. It's a positive statement. Hands to ourselves. I can visualize that and I can do that. I could also model it as a teacher.

Don't run. The action in that statement is run. Instead, say, "Walking feet." As you make statements more positive the child's brain is starting to get rewired to hear the positive things. Stop screaming. What do we do? We scream. Instead, say, "Use indoor voices" or, "Use quiet voices." Don't rip the pages. Instead, turn the pages. You've now turned their brain to think a little bit differently. No climbing on the shelf. Their brain thinks, "Let's climb on the shelf." Instead, try saying, "Feet on the floor."

What comes into play here is something called deductive reasoning, and that's what children know and what they don't know. When we say things like, "Don't climb on the shelf," or "No climbing," to a child they often freeze because they don't know what to do. They might think, "I just heard climb on the shelf. It's what I'm doing, but the way you said it, clearly I'm in trouble and you're kind of yelling so I don't know what to do."

Children don't have that deductive reasoning, so when you say it in a positive manner, you're actually giving them the appropriate action. Keep that in mind when we're talking. We don't want to say the negatives, we want to say the positives.

Activity

Here's a fun activity to do with your colleagues, staff members, team or your classroom. Think about the words no, don't, and stop. We saw a few of those examples in figure 2 such as no climbing, don't rip, and stop screaming. There are two ways to do this activity. You can either get a sheet of those really tiny stickers, whether they're little happy face ones or the ones that you use at yard sales, or you can make boxes on a piece of paper and put everyone's name in a box. Then, the No, Don't, Stop game starts. Any time you hear someone else in your room say the words, no, don't, or stop, they either get a sticker or they get a tally mark in their box.

This is extremely eye-opening for people. You don't realize how many times you say things in the negative. What you're doing is saying the negative word or the action word that you really don't want them to be doing. Then what does their brain do? It goes to the action word and they actually do it. If you hear your colleague say, "No running," she gets a sticker or a mark in her box. By the end of the day, it's unbelievable how many stickers somebody has all over their shirt or how many tallies they have in their boxes. This activity really opens your mind to how you are saying things and how you are speaking. It also gives you the opportunity to change it the next day. It takes a lot to change this habit, but I will tell you, it does work. If you kept this tally sheet or you kept those stickers going for a week, the number that you have on Friday will be drastically less than it was on Monday. It really is just a practice that you have to keep doing.

One time I was the director of a center and I did this activity during a live training with my staff. One of the teachers came to me at lunch and was just covered with stickers. There were probably 50 stickers on her shirt. I went down to her room and I said, "Guys, are you being a little too hard on Miss Michelle because she's got a ton of stickers on her shirt." They said, "No, it's the funniest thing. When she says something to a student or a child, she says, 'no, no, no.'" Guess what they were doing? Bam, bam, bam, three stickers for every time that she said, "No, no, no." It really is an eye-opening activity. It's a fun activity, but always remember the objective behind the activity is to re-teach yourself how to say things more in the positive.

Deductive Reasoning

In the last section, I mentioned something called deductive reasoning. Deductive reasoning is the ability to draw on previous experiences to help you make a decision. You learned at some point that the stove is hot or fire is not good, so you don't touch the stove and you don't touch fire. You may have 18, 30, 50, or 70 years of experience in being able to draw on everything that's happened in your life up until this point to ensure that you don't do it again. Children don't have this. They've only been alive for one, two, three, four, or five years. They don't have a lot of deductive reasoning, so they need you to help them understand as they are trying to learn life lessons.

A really good example of deductive reasoning is a child climbing on the cots. Cots aren't something that children have at home. They just have their bed, but what they might experience at home are stairs. They might experience ladders or steps to get up the slide when they are at the playground or at a community center. When they see the cots stacked up maybe they think, "Well this really looks a lot like things that I've seen in previous places that I climb. So let me try climbing these cots." They don't realize that's not what they're for. There are a lot of things in your center that families don't have at home because we are grouped based, not one-on-one. Children are using the little deductive reasoning that they have to place, "What is this stack of really cool things?" You might have a staggered bookshelf that looks like steps and toddlers are climbing it. It's likely because they don't realize that it's used for books. For them, in their brain, they are using the limited deductive reasoning that they have and the life lesson that they know that is something to climb.

Another good example is that children are very familiar with cats and dogs and things like that. You might introduce them to farm animals through a thematic unit, but it's not until they physically see a sheep that they might call it a dog at first because that's their association. They see dogs and cats all the time, but they don't see sheep all the time. When they see a furry animal that has four legs, a little nubby tail, ears and is walking around, their limited deductive reasoning tells them it's a dog until they start to really understand that it is a sheep. That's where the life lessons come in.

I'm telling you this because when children are not behaving the way they're supposed to and are climbing the cots or climbing the bookshelf, we need to really focus on the way we speak. We need to put things in the positive. Avoid saying, "No, don't, stop" or negative verbiage first to get their brain to trigger the wrong action word. Tell them what they can do or what the appropriate use is for that apparatus, such as the cots or the bookshelf. Also, tell them when is the appropriate time and place for the action that they're doing. Let's practice this.

Speaking the Language of Life Lessons

Figure 3. Situation and responses.

Let's say a child is climbing the cots. Your words to that child should be positive, not negative. For example, "Maddie, I need your feet on the floor." Need is a very specific word. The reason I put need here is that need says that it's not a choice. I need means I'm in control. Need means it's not a choice. The action is feet on the floor. You're telling the child who has their feet on the cots or on the bookshelf that his/her feet need to be on the floor. It's language that he/she can understand and it's in the positive. You're not saying, "Oh my gosh Maddie, no climbing," because now she's freezing and she doesn't know what to do. Usually, your next statement is, "Get down," but that's really not the best way to give those children those life lessons that we need. We want to speak the language of life lessons.

If you have a child who is climbing the cot or the bookshelf your response might be, "Maddie, I need your feet on the floor." Now let's take that one step further and make sure Maddie really is learning from this experience. One way to do that is to say what we need, what's appropriate with the item or object, and what she was doing and where it is appropriate to do the action. For example, "Maddie, I need your feet on the floor because cots are for sleeping." Remember, Maddie does not have a stack of cots at home, so this is still a learning experience for her. Add to your statement to her, "You can climb when we get outside." You are not saying that the action she's doing is wrong, you are just telling her where she can appropriately do that action. Let's practice with a few other situations.

More Examples

Child is ripping the pages of a book

We don't want to say, "Don't rip the pages." We want to say, "Turn the pages of the book," or, "I need you to turn the pages of the book. Books are for reading. If you want to rip, let's go over to the sensory table." Remember, I means you're in control and need means it's not a choice. The sensory table is where you can have paper and tissue paper and other things that you can let them rip. They can throw the paper they rip in a box and use it for their art project later. Remember, include what they could be doing, what the item is really used for, and where can they do the action that they were doing.

Child is throwing blocks

For this situation, you could say, "I need you to build with the blocks. Blocks are for creating towers and houses." They need to understand that. Not a lot of children have big sets of wooden blocks or big cardboard boxes at home. They may have some Legos or small sets of blocks, but they usually don't have the variety or amount of blocks that we have in a childcare center. You can add to that and say, "Blocks are for building and creating. I need you to build towers or play nicely with the blocks. If you want to throw, let's bring the balls outside with us and you can throw there." Throwing is a natural, large motor activity and it's okay for children to throw, but you want to teach them when is the appropriate time. Use the positive language of what they should be doing, the appropriate use for the materials that they're doing it with, and then the appropriate time for when they're doing the undesired action.

Child is eating playdough

We definitely don't want children to eat playdough, even though we use the safe one that's okay to eat but doesn't taste too good. In this situation, you might say, "I need you to play with the playdough with your hands (or squish it with your hands). Playdough is for creating, for rolling, or for squishing in between our fingers. If you're hungry, you can eat a snack/lunch. Snack/lunch is in two minutes." Maybe the child is really hungry and needs to eat something now. Depending on the situation, you might specify where to play with the playdough and say, "I need you to play with the playdough with your hands on the table."

Child is running in the hallway

For this situation, you could say, "I need you to use walking feet. We share the hallway with friends and I don't want you running into anybody else or getting hurt. You can run when we get outside (or in the multipurpose room)." Again, you're not necessarily telling the child that the action he/she is doing is wrong because it's not, it's natural. You're letting the child know what you need him/her to be doing which is appropriate, what the area or the activity or the materials that they're playing with is really used for, and then where he/she can do that action appropriately at the right time.

It's going to take a while for you to practice this. I will tell you that it's hard to work as a team and to reprogram the way you say things. You're going to find that the children are going to respond to you amazingly the first day or two. Then on day three, it's going to crash and blow up. The reason that's going to happen is that it's new and you're all on the same page of saying things differently to the kids. They're going to feel that excitement exuding from you and they're going to respond. Then on day three or four, they're going to realize something's up and they're going to go back to testing their boundaries. The minute they see you go back to your old ways, you've actually lost the progress that you made.

I'm going to be very honest with you. I've seen this happen for over 20 years. Things get really good because it is novel, then it takes a turn and you think, "Well, that didn't work." A lot of times that is why teachers give up on new ideas or give up on advice they may have gotten because they don't realize there will be that ebb and flow. The children get it and then they don't get it. They are trying to test you and see if you could just go back to the old ways. Then, if everyone on the team stays consistent, it goes back up and that's where it stays. You just have to ride out that first dip because it's totally worth it in the end if you're all consistent.

Another key to being successful at this is being consistent. One teacher can't use this new language and really understand the life skills, expectations, and objectives and everybody else still be doing their own thing. You have to come together collaboratively as a team. Whether you are a lead teacher and watching this or you are part of a team, if you work full-time or part-time, it doesn't matter. Share this knowledge with your team. The only way that you can do this and really change some of the behavior and make those life lessons stick for children is to do this consistently together.

Sarcastic Statements

This is one of my favorite activities to do when I have live groups of people in front of me. It's very enlightening. As a society, we are extremely sarcastic. It's hard because people from other cultures don't understand sarcasm. It's very hard for people who have moved to the United States from other countries to grasp that when they first come to the country or when they're first meeting with somebody. It's just what we do. We talk with our hands and we are very sarcastic. That tends to carry down into the classroom. Children are just like our neighbors and our friends from around the world. They don't understand sarcasm. When you speak to them in that manner, you're really not teaching them anything.

Take a moment and write down all the sarcastic statements that you have heard being used with children. It might be something you have heard said to a child or something you have said to a child.

There's no judgment here. That's why you are all here. We are here to learn how to do things because there's often a better way. The best part about being a teacher is you are not only teaching others, but your heart and mind are also always open to learning new things.

I want you to really think about the statements that you say to children. I'm going to share some of the favorites that I've heard, but I want you to really reflect on the things that you say to children. Share this with your coworkers.

Do I look like your mom?

One of the things that I have heard is, "Do I look like your mom?" Play that out in your head. A child comes up and accidentally calls you Mommy. That is really touching, however, I have heard teachers respond, "Do I look like your mom?" For us as adults, it may be kind of funny, but we're being sarcastic. But what does a four-year-old think of that? The four-year-old is probably thinking, "Um, no, I made a mistake, but I really don't like that tone you just gave me. Now I'm kind of embarrassed and ashamed that I made that mistake."

Do you see how that can be taken by a four-year-old? They don't have that deductive reasoning. You are responsible for teaching them life lessons, but you sarcastically say to them, "Do I look like your mom?" It's belittling. It's one of those things where that child has no response that they can say to you. So a lot of times, they stumble over their words and say, "Oh, oh, um, Miss Jennifer," and you say, "Okay, yes, how can I help you?" You followed up with another sarcastic statement, because sometimes it's not always what you say, it's how you say it. When you say, "Okay, how can I help you," the child might think, "I don't want you to help me anymore, especially when you say it snidely like that" because he/she just accidentally called you Mom.

Really, you just did that?

Here's another one I often hear. "Really, you just did that?" Yes, they did. They did just make a mistake or spill something. Maybe they took a toy from somebody else. What really happened is the child displayed a behavior that is not acceptable, not appropriate, or that breaks your classroom rules. So instead of being positive and explaining that the behavior is not acceptable, your response is, "Really?" As the child thinks, "Uh, yeah, I just took it because I wanted it." You didn't teach the child anything. You just responded with a sarcastic question that they really don't know how to respond to. Instead, try talking to them more positively as we've been discussing. For example, "I need you to give your toy back to your friend. Taking toys is not very nice. You made her sad. If you want a doll, let's go over to dramatic play. I can get you one and you can use that."

No thank you.

Another one I have heard when I have seen children misbehave and the teachers say, "Uh, uh, no thank you." Now you're just telling them, "No," but you're being polite about it. I told them no but at least I taught them manners, too. That's not the point of it. The actual point is, "No thank you" does absolutely nothing for teaching children the right things to do. If they went and played somewhere or they're climbing the cots or they're throwing puzzle pieces off of the table onto the floor and your reaction is, "Uh uh, no thank you," that doesn't teach them that puzzles need to stay on the table, I need you to pick that up, or if you want to throw, we can throw balls outside. It doesn't teach them to come down off the cots and put their feet on the floor. Sarcastic statements really don't have any type of impact.

Here are a few other sarcastic phrases teachers have admitted to saying.

- "Seriously."

- "Do I look like I'm smiling/laughing?"

- "Did you just do that?"

After self-reflection, teachers realize that there's really no value in saying those things. We are a very sarcastic society. There are a lot of lessons and poignant points being shared in this course. Keep in mind what your objective is, are you teaching life lessons, and remember that the brain goes to action words. Sarcasm doesn't really work on kids.

Life Lessons vs. Developmental Milestones

Let's talk about life lessons versus developmental milestones. We've talked about developmental milestones this whole time. Those are the key skills that young children should master within a certain age range if they are progressing and advancing cognitively and physically at a typical pace. This includes your curriculum and your scope and sequence. These are all of the skills that the children should be learning to make sure that they are progressing appropriately. These are probably the things that you're pulling out when you're having parent-teacher conferences and it's probably the list you're pulling out when you're seeing some red flags for children's development.

The difference between developmental milestones and life lessons is that life lessons are activities geared toward the skills that children need later in life, socially, physically, emotionally and more. Life lessons are how you can help make them good people. You want to make them smart and well-rounded and you want to make sure that the physician says that they're right on target. You want to make sure that their kindergarten and first-grade teachers are saying, "Wow, what center did they come from? They are amazing." But you also want those people to be saying, "Wow, they're great kids. They're kind, they have manners, and they think of others." Those are the other things you want them to be saying because those are the skills that are going to get them further in life and really make the world a better place in the end. If you can be anything, be kind, right. Those are the things that we want to teach children.

It is an extremely delicate balance. As great teachers, you need to find the life lessons that are above the milestones. If you can teach them that it is acceptable to come together and be in a large group and be engaged, then they're going to get all those developmental milestones. They're just going to happen like osmosis. But if you're so busy setting expectations that the children can't meet, you're actually going to be too busy correcting behavior, moving children, and redirecting them. You're going to be so involved with those things that when you get around to the developmental milestones and checking them off, you may not check as many as you would have as if you really worked on identifying what the objective is behind the areas of your classroom and the skills we've been talking about, just letting them fall into place.

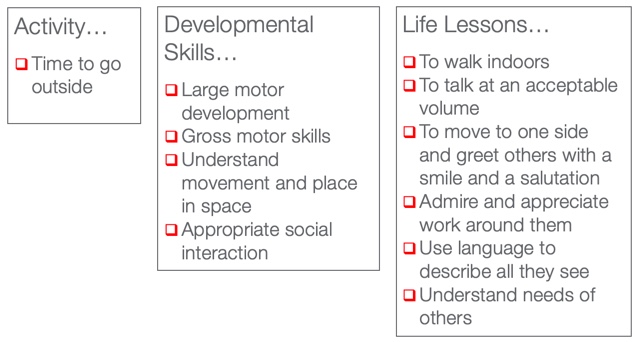

Figure 4. Finding the life lesson.

Let's do a quick activity on finding the life lesson. Let's say it's time to go outside. The developmental milestones or skills are that there will be some large motor development going on, they will be practicing gross motor skills, they will understand their movement and their place in space, and there will be appropriate social interaction. Those are the developmental milestones or key points in your curriculum that you need to meet. However, the life lessons are:

- To walk while they're still indoors

- To talk at an acceptable volume, which might be as they're walking past the baby room as I mentioned earlier

- To move to one side and greet other people with a smile and a salutation

- To admire and appreciate the things around them, such as bulletin boards (which includes teaching them not to rip somebody else's projects down because they belong to others)

- To use appropriate language to describe what they see

- To understand the needs of others

Throughout your day, you're going to be looking at these different areas.

- Group Time/Circle Time

- Snack or Meal Time

- Small Group Interactions/Learning Centers

- Storytime

- Music & Movement

I want you to ask yourself, what are the milestones that naturally occur during these times of the day and what are the life skills that I could be teaching during each of those times? As great teachers, I know you can balance those. I know that you can be objective and you can think about what those are and be able to meet both of them.

I want you to think of one thing that you're going to do differently after going through this course. It might be the No, Don't, Stop activity or doing a little bit of reflecting on if you talk sarcastically. You might look back at your lesson plans and think about what the true objective is for each lesson. If you really look at that, maybe you won't frustrate yourself, have unclear or over-leveled expectations of the children, and everything will settle down. You might change the things that you ask children to do that we don't do as adults, such as catch a bubble or walk with your finger on the wall. You might change the way you speak and start saying, "I need you to do this because the cots/bookshelf/table/toys are used for this. But if you want to do that action, you can do it here instead."

You have a lot of things to think about and a lot of things to reflect on. I want to say thank you for all that you do. You really are shaping the children of tomorrow and you are shaping the world. Think about that. You are not just making smart kids, you want to make good people too.

References

Citation

Romanoff, J. (2019). Catch a Bubble, Finger on the Wall, Are We Teaching Them Anything at All? continued.com - Early Childhood Education, Article 23387. Retrieved from www.continued.com/early-childhood-education