Editor's note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Collective Trauma and Building a Trauma-Informed Culture: Working with Parents, presented by Nadia Tourinho, MSW, LICSW, LCSW-C.

This is part one of a four-part series titled Collective Trauma and Building a Trauma-Informed Culture. Once you finish part one, move on to parts two, three, and four.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Describe how to use effective trauma-informed care techniques when working with parents, children, and staff.

- Identify how to look beyond children's behavior and actively listen to the message children communicate with their behaviors.

- Identify techniques non-clinical staff must develop to provide effective trauma-informed care in the workplace.

- Explain necessary strategies educators must incorporate in the classroom to create a trauma-informed sensitive environment.

Parents' Understanding of Trauma

When working with parents, it is important to provide some education on exactly what trauma is. As we go through this course, all the information is helpful to share with parents. There's a lot of talk about trauma in the media, and we want to help parents understand what they and/or their children have experienced and its effects. What is trauma? Individual trauma results from an event, series of events, or a set of circumstances experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or threatening and can have lasting adverse effects on the individual's functioning and physical, social, and emotional well-being.

Research has shown that children are particularly vulnerable to trauma because of their rapidly developing brains. During traumatic experiences, a child's brain is in a heightened state of stress, and fear-related hormones are activated. Although stress is a normal part of life, when a child is exposed to chronic trauma, like abuse or neglect, the child's brain remains in this heightened pattern. Staying in this heightened state can change the child's emotional, behavioral, and cognitive functioning to maintain and promote survival. Over time, these traumatic experiences can significantly impact a child's future behavior, emotional development, and mental and physical health. We need to communicate that and educate parents, so they understand and know what is going on with their child.

How Trauma Affects the Brain

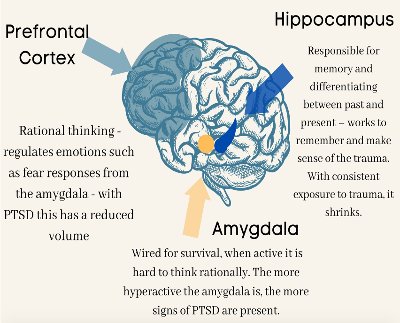

To help parents understand what is going on with their child, they need to understand how trauma affects the brain. When someone experiences trauma, three parts of the brain are affected: the prefrontal cortex, the amygdala, and the hippocampus.

Figure 1. Parts of the brain affected by trauma.

The prefrontal cortex helps to control the activity of the amygdala and is involved in helping people learn that previously threatening people or places are now safe. The connection between the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala is sometimes not as strong in children that have experienced trauma. As a result, the prefrontal cortex is not as active at reducing the amygdala's response to people, places, and things that are, in fact, no longer predicted as dangerous. This can lead to persistent elevation in fear and anxiety from cues that remind children of the trauma that they have experienced.

The amygdala is designed to detect and react to people, places, and things in the environment that could be dangerous. This is important for safety and survival. After trauma, the amygdala can become even more attuned to potential environmental threats, leading a child to closely monitor their surroundings, ensure their environment is safe, and react strongly to new people. This heightened attention to potential threats in their environment can make it hard for children to pay attention in school, go to new places, or interact with people they don't know. They're almost always in this arousal stage where they are hyper-alert about what could go wrong because their amygdala is altered by trauma.

The hippocampus is involved in learning and memory. Trauma affects the development of the hippocampus, which can impair learning and memory in children, such as the ability to learn and remember information about the surrounding environment. As a result, children who have experienced trauma may not be able to retain information about how to tell if one situation is safe and another is dangerous, leading them to experience a harmless situation as dangerous.

Let's go a little bit deeper. With trauma, there are physical brain changes such as smaller brain structures, fewer brain cells, and broken connections between brain cells. It lowers emotional control as well. The brain cannot process emotions, leading to mood disorders and behavioral issues. This is why children are often not able to control their emotions. Trauma lowers learning ability, causing trouble concentrating, learning, paying attention, and lowering creativity. It also lowers behavioral control. The brain changes make it hard to control impulses and behaviors and difficult to form relationships. As you work with children and families, it is crucial to keep these effects on the brain in mind. Make sure to educate parents on these changes to understand better what may be happening with their child.

Types of Trauma

There are several types of trauma, including big "T" and little "T," acute trauma, chronic trauma, and complex trauma. Big T trauma includes serious injury, sexual violence, and assault, or life-threatening experiences. Threats of serious physical injury and sexual violence can cause intense trauma, even if the person is never physically harmed. Small T trauma includes highly distressing events that affect individuals personally but don't fall into the big T categories. This includes non-threatening injuries, emotional abuse, the death of a pet, a breakup, a challenging relationship, and a job loss.

Acute trauma results from a single form of a distressing event, such as an accident, rape, assault, or natural disaster. The event is extreme enough to threaten the person's emotional or physical security and creates a lasting impression on the person's mind. Chronic trauma happens when a person is exposed to multiple long-term and prolonged distressing traumatic events over an extended period. Chronic trauma may result from a long-term serious illness, sexual abuse, domestic violence, bullying, or exposure to extreme situations such as war. Several events of acute trauma, as well as untreated trauma, may progress into chronic trauma. Chronic trauma symptoms often appear after a long time, even after years. Keep this statement in mind. The symptoms of chronic trauma may not appear for a long time after an event, even after years. The symptoms are deeply distressing and may manifest as unexplainable emotional outbursts, anxiety, extreme anger, flashbacks, fatigue, body aches, headaches, and nausea.

The last type of trauma is complex trauma. This is the exposure to multiple traumatic events or experiences. The events are generally within the context of interpersonal relationships. Complex trauma may give the person a feeling of being trapped and often severely impacts the person's mind. It may be seen in individuals who have been victims of childhood neglect, domestic violence, and family disputes. It affects the person's overall health relationship and performance at work or school. It's imperative for us to be aware of these types of trauma and help parents understand them, especially if they do not know what it means if their child has experienced trauma. Often, if people understand why things such as challenging behaviors occur and what may be causing them, they're more understanding of the situation.

What Does Childhood Trauma Look Like in Adults?

When working with parents, we must be aware that they may be dealing with their own trauma. Their child experiencing some level of trauma can sometimes trigger parents. Childhood trauma in adults can impact experiences and relationships with others due to experienced feelings of shame and guilt. Childhood trauma also results in feeling disconnected and unable to relate to others. Studies have shown that adults who have experienced childhood trauma are more likely to struggle with controlling emotions and have heightened anxiety, depression, and anger. Think about coping with that while raising a child who also has been impacted by trauma. What would that do to that parent? It is crucial to keep this in mind when we are working with parents.

The SAMHSA's National Child Traumatic Stress Initiative (NCTSI) reports that by age 16, two-thirds of children report experiencing at least one traumatic event. That gives you an idea that there are many parents out there who have experienced some level of trauma. If these statistics continue to be correct, unfortunately, their children will also experience some level of trauma. There are many different ways in which symptoms can manifest for adults living with untreated childhood trauma, as seen in the table below.

| Emotional Symptoms | Physical Symptoms | Behavioral Symptoms |

| Anger | Poor concentration | Compulsion |

| Unresponsiveness | Shakiness | Eating disorders |

| Anxiety | Night terrors | Impulsiveness |

| Emotional outbursts | Lack of energy | Isolation |

| Depression | Physical illness | Numbness or callousness |

| Panic attacks | Sleep disturbances | General disorientation |

Remember, with chronic trauma, a person may only feel the symptoms years later, often after a trigger. An adult may begin to have flashbacks, more memories, and night terrors. Understand that it may feel like there's a block between you and the parents you're working with if they're dealing with symptoms like this. It's not necessarily you, the provider, that is the block. It might be because the parent is also dealing with things within themselves, or they may feel shame and guilt if the parent feels shame and guilt over a previous trauma that often spreads to their child. They feel like generational trauma is continuing, and they tried their best to protect their child, but this also happened. The bottom line is to think about the child even if the parent has also experienced trauma.

How Trauma May Affect Parents

As a result of past traumatic experiences, parents may have difficulty keeping themselves and their children safe and healthy. Some parents might be overprotective, while others may not recognize the real dangers that can threaten their children. That goes back to the part of the brain that is damaged. If trauma is not addressed when it happens, that part of the brain will not heal properly. A parent might resort to coping in unhealthy ways, such as using drugs or alcohol. They may react more strongly or negatively to things, have a harder time understanding or controlling their emotions, behaviors, and words, or be more susceptible to future trauma such as domestic violence.

They can also find it difficult to trust others, especially people in positions of power. They may be more vulnerable to trauma reminders or triggers when a sound, smell, or feeling brings back the experience of trauma all over again. Reminders may cause parents to overreact to situations other parents might not find difficult. They may become numb or shut down, even when interacting with their child. They may misread your words or intentions. These difficulties can indicate the presence of trauma. If you know they might have experienced some trauma, don't take things personally. How they might interact with you could be in regards to their trauma or even their own fears that now this is happening to their child.

Trauma Misconceptions

There are a lot of misconceptions out there regarding childhood trauma. Childhood trauma in adults doesn't necessarily mean they will be unable to have a full life. Many people have misconceptions when it comes to adults affected by childhood trauma. The first misconception is an individual who was abused and/or neglected as a child will abuse and/or neglect their children. That is very far from the truth. Just because someone has been abused or neglected does not necessarily mean they will do that to their child. That is a very longstanding misconception of trauma, but there are people that, unfortunately, still believe that. Mostly, parents will not do the same thing to their children.

The second misconception is that abused and neglected children will become deviant adults. Again, that is far from the truth because plenty of people have experienced trauma, gone to treatment, managed their trauma and symptoms, and can have fulfilled lives as adults. The third misconception is that the effects of abuse and neglect are irreparable, and the adult won't live a full life of recovery. Again, with the proper treatment and support, individuals can learn how to manage their symptoms. Recovery looks different for everyone, whether it's an adult, a child, or a youth.

Empathy

When working with our parents, it's vital to show empathy, especially if this is someone who also has experienced trauma. Empathy is the ability to put yourself in the place of another and understand someone's else feelings by identifying with them. With empathy, you put yourself in another's shoes and view the situation through their eyes to get a real sense of their experience. Rather than just feeling bad for the other person, showing empathy involves sharing their feelings. This is very important because people know when you're not being genuine with them. If we are trying to help the child, we must also work with the parent.

When someone shares something difficult they are dealing with, there are times you don't have anything to say in response to what the person just said to you. Just stating that it sounds like they're having a difficult time is a lot better than pulling something out of nowhere to try to show empathy because then you're not. Also, when showing empathy, stay away from the words "at least." For example, at least X, Y, and Z, or at least now you can keep your child protected, or at least now you're educated. That's not showing empathy. That drives the connection away. It's extremely important to show empathy because then we can genuinely say that we are staying within the trauma-informed care model because we're working with everyone.

Working with Parents

When working with parents of children who have experienced trauma or who have experienced trauma themselves, there are many things to keep in mind. As we've discussed, parents may experience many different feelings. When trauma happens, child welfare often gets involved, especially if it's sexual trauma, domestic violence, or physical violence, which can cause more stress for parents.

One thing to keep in mind is don't take difficult reactions personally. That applies whether the parent has trauma or not. Understand that parents' anger, fear, resentment, or avoidance may be a reaction to their traumatic experiences rather than to the child or you. Remember that parents who have experienced trauma are not bad. Blaming or judging them will likely worsen the situation rather than motivate them to change. Approach working with parents on a strengths base versus focusing on the bad.

Show parents that you genuinely care by complimenting their efforts to keep their children safe. Support them in their role as parents by asking for suggestions on how to care for their children. This can be important if you're aware that the particular child has had some level of trauma. Ask the parent what you do at home to ensure that little Johnny feels safe. If the parent says Johnny really likes his blue blanket, then ask if the blue blanket could be brought into the classroom to help little Johnny feel safe. Then you're working together.

Bring up the trauma-informed model because we're working together to ensure that little Johnny feels safe at all times. Including the parent, especially if it's a parent with some trauma, and complimenting them on keeping their child safe will encourage and motivate the parent, especially if they feel guilty that now this is happening to their child when it also happened to them. When differences of opinion in parenting beliefs and practices arise, understand that they may be reacting to feelings of fear, inadequacy, or losing control. Focus on the child to keep disagreements from becoming personal.

Model direct and honest communication. Share your observations instead of your opinions when presenting information that may be hard to handle. Similarly, be aware of and openly acknowledge your own mistakes. Staying focused on strengths is essential. For example, let's say an educator is communicating with a parent and sharing that they have observed that their child's homework is not done in the child's handwriting. The educator might feel that the parent is the one that is doing the work. Pointing it out in a strength-based way saying, I've noticed that some of the work that has been sent in has been in your handwriting. Can you tell me more about that and what's going on? Maybe the parent is helping the child to do their work, but because the child is under significant stress, the parent is the one that is doing the work, and the child is not learning. For an educator, that can be concerning. But if you go into an attack mode, the parent will probably not be receptive to what you have to say. A better option is to say something like, I've noticed that X, Y, and Z are happening. Can you tell me more about when that's happening at home? Again, be open and honest about your mistakes and apologize for them. Take accountability when you also make a mistake because we are all humans. Whether you are a parent or a professional, we all make mistakes.

If child welfare has gotten involved with the child and parents, ensure you establish clear boundaries and expectations with birth parents and case workers. Be consistent, and when you make a commitment, follow it through. Work hard to agree rather than staying stuck on being right or trying to win. Remember that visits, court hearings, and case conferences are difficult for parents and children. Work with them to set a routine for these encounters, especially if they may return to the classroom after one of these situations. These situations will be difficult for the parents and the child because they don't know what will happen. Setting routines in the classroom can help.

Stay calm, even-toned, and neutral during stressful situations. You'll be less likely to generate arguments. If there's no kinship provider, always ask the birth parent how they would like to be addressed. This conveys respect. Again, this is within child welfare. If the child is in a childcare program, it's always good to keep the parent in the loop as best as you can as an educator. The parent will feel like they're still connected with their child, and the educator respects them enough to let them know some about their child and how they're doing in school. That builds that relationship with the parents. Lastly, remember that things will not always go smoothly, even if you try as hard as you can. Work towards mutual trust while considering that it may take some time.

Understanding the Child's Behavior

Not every parent has untreated trauma. As I've mentioned, some parents have gotten help with their trauma or don't have any trauma. With trauma-informed care, the main idea is not to think about what is wrong with the child but, instead, think about what happened to this child to cause this behavior. We must educate parents on what to look for or what they are seeing and how that relates to trauma. Understanding a child's behavior is a part of this. Parenting a traumatized child may require a shift from seeing a "bad kid" to seeing a kid who has had bad things happen. Let's talk about some signs of trauma in children of different ages.

Young Children (Ages 0-5)

Young children, ages birth to five, can be irritable and fussy, startle easily, or difficult to calm. They may have frequent tantrums and clinginess and be reluctant to explore the world around them. Their activity levels may be much higher or lower than their peers. They may repeat traumatic events over and over in dramatic play or conversation. They may have delays in reaching physical, language, or other milestones. If a parent says, hey, my child is so clingy, and you're aware of the trauma, you can educate the parent and let them know that might be a symptom of trauma, especially between those ages.

School-Age Children (Ages 6-12)

Between the ages of six and 12 years, it's a little bit different. They may have difficulty paying attention, are quiet or withdrawn, have frequent tears or sadness, or often talk about scary feelings and ideas. They may have trouble transitioning from one activity to another. They may fight with peers or adults, display changes in school performance, or want to be left alone. They may eat more or less, get into trouble at home or school, or have frequent headaches or stomachs without any cause. Behaviors common to younger children include thumb sucking, wetting the bed, or fear of the dark. These are some behaviors parents can look out for between the ages of six and 12.

Teens (Ages 13-18)

Teens will display different behaviors, including talking about the trauma consistently or denying it happened. They may refuse to follow the rules or talk back frequently. They may always be tired, sleep much more or less than their peers, or have nightmares. They may display risky behaviors, fight, or not want to spend time with friends. Teens may begin using drugs or alcohol, run away from home, or get into trouble with the law.

Trauma Triggers

Someone with any level of trauma will likely experience some triggers. When children behave unexpectedly and seem irrational or extreme, they may experience a trauma trigger. We need to understand these triggers and be able to educate our parents about them. A trigger is some aspect of the traumatic event that occurs in a completely different situation but reminds the child of the original event. Examples may be sounds, smell, feelings, places, postures, tones of voice, or emotions.

Children who have experienced traumatic events may reenact past patterns when they feel unsafe or encounter a trigger. For example, if they usually don't act a certain way and suddenly act that way, and you know they have some trauma, understand that they might be having a trigger. Especially if the child is between the ages of zero and five, they might not be able to express that adequately. As we work with parents, we need to be able to help them to see that.

Depending on whether the child has a fight, flight, or freeze response, the child may appear to be throwing a tantrum, willingly not listening, or defying you. However, responses to triggers are best thought of as reflexes that are not deliberate or planned. When children's bodies and brains are overwhelmed by a traumatic memory, they cannot consider the consequences of their behavior or its effects on others. When they feel highly overwhelmed with that memory, maybe all they know how to do is act a certain way to help them calm down.

It's our job as professionals to help parents learn how to control that when they are in their home and what to look for versus thinking, oh, there goes little Johnny again, he's having a little tantrum. Let's put him in his room. Isolating the child would not be helpful at all. That's causing more trauma because now the child might want to express what is happening, and they might not have the words to do it. As a parent, they're just putting them in the room because they don't know how to handle the behavior.

Help parents understand that this might be a trigger that the child is having. If the child was completely fine five minutes ago, and all of a sudden now the child is throwing a tantrum, and you have no idea what triggered it, that is when we need to think about, maybe my child smelled X, Y, and Z, perhaps it was a feeling, maybe it was a touch. Maybe something caused that trigger to come onto my child for them to act this way.

Helping Parents: Help Their Child

Here are some things we can encourage parents to practice with their children in the home. We can continue the same practice in schools, therapy, or daycare. Respond, don't react. Parents' reactions may trigger a child or youth who is already feeling overwhelmed. Some children are even uncomfortable being looked at directly for too long. When a child is upset, do what you can to keep calm. Lower your voice, acknowledge the child's feelings, and be reassuring and honest. Avoid physical punishment. This may make an abused child's stress or feeling of panic even worse. Parents must set reasonable and consistent limits and expectations and praise desirable behaviors. These are some things we can also do in classrooms when trying to correct certain behaviors.

Don't take the behavior personally. Allow the child to feel their feelings without judgment. Encourage the parent to help the child find words and other acceptable ways of expressing fears and offer praise when these are used. With trauma-informed care, it is recommended that responses are consistent both in the home and in the classroom or daycare. Listen. Don't avoid difficult topics or uncomfortable conversations, but don't force children to talk before they are ready. Let children know that feelings are normal after a traumatic experience. Take their reaction seriously, correct any misinformation about the traumatic event, and reassure them that what happened was not their fault.

Help the child learn to relax. Encourage the child to practice slow breathing, listen to calming music, or say positive things such as, I am safe now. Be consistent and predictable. Develop a routine for meals, playtime, and bedtime. Prepare the child in advance for changes to new experiences. Be patient. Everyone heals differently from trauma, and trust does not develop overnight. Respecting each child's course of recovery is extremely important. Allow some control. Reasonable, age-appropriate choices encourage a child's sense of having control of their own life. Encourage self-esteem. Positive experiences can help children recover from trauma and increase resilience. Be emotionally and physically available. Some traumatized children act in ways that keep adults at a distance, whether they mean to or not.

Effective Interventions

As professionals, we can use some effective interventions in the classroom and encourage parents to use them. One intervention is to increase the child's feeling of safety. This could be done by providing a safe place in the classroom and one in the home. Another intervention is to teach the child how to manage emotions, particularly when faced with trauma triggers. It is very important to teach the child how to self-regulate once we have realized that they have a trigger. Third, help the child develop a positive view of themself by helping them view themselves differently. If they have shame and guilt, you can also help them process that.

Last, give the child a greater sense of control over their own life. That can be something like providing options and letting the child choose. For example, let the child choose what they would like for dinner at home, such as burgers or hot dogs. In the classroom, you can allow a child to sit in two different places or provide two different activities they can do. It helps children to have a little control over being in situations where there is no control.

Helping Yourself: Helping the Child

To take good care of a child, you must take good care of yourself. Be honest about expectations. Encourage parents to have realistic expectations when parenting a child with a history of trauma. If you are in the classroom, you should also be realistic about your expectations for this child. Celebrate small victories. Take note of the child's improvement, both in the classroom and at home. Don't take the child's difficulties personally. The child's struggles are a result of the trauma they have experienced. They are not a sign of failure in parenting.

Encourage parents to see that when their child acts a certain way, it likely has nothing to do with their parenting but, unfortunately, the circumstances their child has faced. People I have worked with in the past might feel that they're failing as a parent or they're not being good enough. If they do have some level of trauma, they feel like it's affecting their parenting because of that trauma. We, as providers, need to be able to highlight that.

Take care of yourself. When I mean yourself, I mean the parent. Encourage parents to make time for things they enjoy doing that support their physical, emotional, and spiritual health. I recommend this for all parents, not just parents who have experienced some trauma. For parents who have experienced some level of trauma, focus on your own healing. If a parent has experienced trauma, they must pursue their own healing, separate from the child.

Seek support, including friends, family, and professional support. As I mentioned previously, sometimes child welfare is involved. Often child welfare has a negative connotation among parents and others who think child welfare is only for abuse and neglect of a child. However, child welfare also provides support for some parents. Encourage parents to seek support from community resources or child welfare. They often have more resources than other programs will have, or they might know more about certain groups that will be able to help the child as well as the parent.

COVID-19 Trauma

Lastly, we're going to talk about the big thing that's going on right now, which is COVID-19, or Coronavirus. This huge trauma has been going on for the last two years or so (at the time this course was created) and is still going on. Many studies have shown a significant increase in parenting stress levels in parents, which in turn represent crucial risk factors for children. There have been other studies that show domestic violence, and child abuse have gone up. Many of these statistics have gone up because many people have been home.

Take a moment and imagine a child who sees people they care about dying or has an uncertainty of not knowing what's going to happen. This is a very stressful time, especially for parents. Because not only do you have to parent, but parent during a pandemic which causes a lot of stress. Imagine having a child with some trauma, and now there's this pandemic. It adds about ten times more difficulty to everything you have to do as a parent. The COVID-19 pandemic does not fit into the PTSD models or diagnostic curricular criteria. Yet research shows that traumatic stress symptoms resulting from this are ongoing and can be very extreme for parenting and children.

As professionals, we can help parents help their children cope with the pandemic. Help the child process their feelings during this unpredictable time. Ensure parents have developmentally appropriate information. Be prepared that children may ask you the same question or bring up the same concerns repeatedly. Try to give a brief but honest response. Create opportunities to check in with the child. Children likely have concerns about their safety and the health and safety of those close to them. To keep them safe, provide reasonable concrete information about what you are doing in the present and immediate future. Again, safety is the number one thing we must always offer when it comes to anything concerning trauma.

Teenagers may want to have more information and may need to talk more. Give them space, but also keep a close eye on how they cope. Create opportunities for discussion. Kids are tuned into their parents' reactions, and it's important to model healthy expressions of emotion. Share how you are feeling and how you manage difficult feelings. It is helpful to let your child know if you are sad or worried while reassuring them that you are there for them no matter what. You can model this in the classroom and suggest parents do it with their children.

Remember, trauma-informed is being aware of triggers and certain behaviors that people might do, especially children. Don't look at the child as a bad kid, but shift the thinking to what happened to this child to behave this way. People don't start acting in a certain way out of nowhere.

References

Anderson, K.M., Haynes, J.D., Ilesanmi, I., & Conner, N.E. (2022). Teacher professional development on trauma-informed care: Tapping into students' inner emotional worlds. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 27(1), 59–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/10824669.2021.1977132

Bridgland, V.M., Moeck, E.K., Green, D.M., Swain, T.L., Nayda, D.M., Matson, L.A., Hutchison, N.P., & Takarangi, M.K. (2021). Why the COVID-19 pandemic is a traumatic stressor. PLOS ONE, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240146

Champine, R.B., Hoffman, E.E., Matlin, S.L., Strambler, M.J., & Tebes, J.K. (2022). "What does it mean to be trauma-informed?": A mixed-methods study of a trauma-informed community initiative. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 31(2), 459–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-02195-9

Kwon, D. (2022). The long shadow of trauma. Scientific American, 326(1), 48–55.

Marzilli, E., Cerniglia, L., Tambelli, R., Trombini, E., De Pascalis, L., Babore, A., Trumello, C., & Cimino, S. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on families' mental health: The role played by parenting stress, parents' past trauma, and resilience. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11450. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111450

National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (2011). Birth parents with trauma histories and the child welfare system: A guide for child welfare staff. https://www.nctsn.org/sites/default/files/resources//birth_parents_with_trauma_histories_child_welfare_chil d_welfare_staff.pdf

Nowakowski-Sims, E. (2022). Integrative body, mind, and spirit interventions used with parents in the child welfare system. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 15(1), 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-021- 00388-4

Nurick, J. (2020, June 9). How trauma affects the brain. Jennifer Nurick. https://www.jennynurick.com/how-trauma-affects-the-brain/

Child Welfare Information Gateway (n.d). Parenting a child who has experienced trauma - child welfare. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/child-trauma.pdf

Thatcher, T. (2018, November 18). Healing childhood trauma in adults: Highland Springs Clinic. Highland Springs.

Trauma in children during the COVID-19 pandemic. NYU Langone News. (n.d.). https://nyulangone.org/news/trauma-children-during-covid-19-pandemic

Unknown. (n.d.). Trauma-informed care. Trauma-Informed Care | Early Connections. https://earlyconnections.mo.gov/professionals/trauma-informed-care

White, M. G. (n.d.). What's the difference between sympathy and empathy? Grammar. https://grammar.yourdictionary.com/grammar/style-and-usage/what-s-the-difference-between-sympathy-and-empathy.html

Yeates, E. O., Grigorian, A., Schellenberg, M., Owattanapanich, N., Barmparas, G., Margulies, D., Juillard, C., Garber, K., Cryer, H., Tillou, A., Burruss, S., Penaloza-Villalobos, L., Lin, A., Figueras, R. A., Coimbra, R., Brenner, M., Costantini, T., Santorelli, J., Curry, T., & Wintz, D. (2022). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric trauma in southern California. Pediatric Surgery International, 38(2), 307–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-021-05050-6

Citation

Tourinho, N. (2022). Collective trauma and building a trauma-informed culture: Working with parents. Continued.com - Early Childhood Education, Article 23799. Available at www.continued.com/early-childhood-education