Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Developing a Yearlong Curriculum Guide, presented by Robin Fairfield, EdD.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Define developmentally appropriate practices.

- Describe the benefits of planning a curriculum.

- Identify and describe the planning process.

Benefits of Planning a Year-Long Curriculum Guide

There are many benefits of planning a year-long curriculum guide. It allows parents and families to have an idea of what is happening throughout the year. They can follow along with you as you progress through the year in regards to some of the things that you will be doing in your program. It is also a benefit to the instructional staff because when you have a year-long curriculum guide, the instructional staff has a focal point for planning. It gives them an idea of what they should be doing throughout the year. It is also beneficial for administrators. When administrators have a curriculum guide for the year, they are able to monitor and assess their program and ensure that the curriculum is meeting the needs of the children. It is beneficial for all stakeholders because the curriculum guide shows that your program is structured and gives them a little bit of knowledge about what you are doing throughout the year.

Definitions

I am going to start by covering a few terms I will use today. I will share the definitions of these terms for the purpose of this presentation.

Developmentally Appropriate Practices (DAP)

The first term we are going to talk about is Developmentally Appropriate Practices, also known as DAP. When we talk about Developmentally Appropriate Practices, we are talking about how what we are doing is age-appropriate, individually appropriate, socially and culturally appropriate, and sometimes linguistically appropriate. This quote comes from the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) but was cited by Kostelnik, Soderman, Whiren, and Rupiper (2019) in a textbook that I have used in the past. The quote from NAEYC says, “When teachers use DAP, they are making decisions about the well-being and education of the children, and they consider their knowledge to guide their thinking.”

When we use Developmentally Appropriate Practices, teachers are key in decision-making. It is really important that teachers understand there are three things they must always keep in mind. The first thing to keep in mind is, what is known about children and how they learn and develop? Here is an example. If a preschool teacher is working with young children in the classroom and their background is in something other than early childhood education, they will not have that deep knowledge of how young children learn. They may not even have a deep knowledge of the importance of play. It is important that we do have that background and that we are thinking of it when we are working with young children.

The second thing teachers must consider is, what is known about the individual abilities of the children in regards to what they can do and what their interests are? Teachers have to consider that for every child in their classroom on an individual basis. All children are different. They do not all come in with the same skills and the same knowledge. The third thing that teachers need to remember is, what is known about the society, culture, and community where these children live? When you are in the classroom and working with children, you may not live in the same neighborhood that these children and families come from. When the children arrive at your door, you need to know where they came from. This is so important because you may come from a neighborhood that is completely in a different city, and perhaps you even drove 45 minutes to get to work. Your community could be very different from the community where the child lives.

There are some things you will need to do in order to really have a good idea of where the children are coming from is. If you are working on an elementary school campus, then you would want to network with the people at that school so you could see what the routines are when children are going to school. Are they walking to school? Are they riding buses? Are they being dropped off by their parents? You need to know what the neighborhood is like before school even starts in the program here. You should be able to drive through the neighborhood, see what is going on, and maybe have lunch in the neighborhood. This will help you understand where the children are coming from.

Another way teachers can find out about a child, their community, and the society that they are in is to do a home visit. Sometimes parents are hesitant and do not want you to come to their homes. If you can get parents to allow you to come when they are home, it is a great place to learn more about the children and families and where they come from.

Curriculum

Our next term is curriculum. Curriculum is not necessarily something that you have to follow exactly. In the textbook by Hendrick and Weissman (2011) called Total Learning, they say, “A curriculum needs to be thought of as everything and anything that a child experiences throughout their day at school.” They also talk about curriculum being a design of experiences or something that happens anytime during the day.

An example of this would be in a daily schedule where a teacher will have written group time or circle time or lesson time. Then they have outdoor time and snack time and all the things that are in a daily schedule. But when a parent or other viewers look at the daily schedule, it appears the only learning that is taking place is when the teacher has the children at this group time or circle time. We want to make sure that curriculum is understood as everything that happens all day. When we are transitioning from indoors to outdoors, we should have curriculum planned because otherwise children will be just running all over the place. There has to be a plan. Every single thing the child does during the day at school is full of teachable moments. Those are also known as curriculum.

Planning

The next term is planning. I consider planning like thinking. Typically, early childhood educators think and plan well beyond the classroom. They think about things when they are at home in the evenings or on the weekend or while running errands. They are always thinking. They have a process and they are mapping out how things are going to go. They think about how they are going to guide and what they need to do to prepare.

According to Miriam Webster, planning is the act or process of making or carrying out plans that include the establishment of goals, policies, and procedures for a social or economic unit. I think it also means that planning is a sequence of steps that we may do in order to achieve an outcome. The other thing is, I think that when you are following a plan, it makes it easier to create activities and it becomes more effective and more efficient. It is often said, be proactive and plan ahead. This is how you will find out how much more you need to do to get to your goal and how far have you come. Planning is the key.

Goal

A goal could mean a variety of things for a variety of people. Take a moment to reflect and think about what a goal is to you.

A goal is a broad-based idea of something you want to accomplish. Sometimes teachers and others confuse goals and objectives because you do need to have goals and objectives to plan activities. However, a goal is a broad-based idea of what you want to accomplish. For this presentation, think of a goal as the desired result and something that you want to accomplish.

Child Outcomes

Our last term is child outcomes. We hope that our child outcomes are achievement and success. We want children to be successful and we want them to achieve. When I first learned about child outcomes, I was a Head Start teacher. The term was used frequently in relation to school readiness. It was a very strong focal point and had to do with what children were ready to do and what they could do to be successful.

When planning curriculum and activities for the young children to be successful, we had to use authentic observations. I am going to talk about authentic observations in a bit. In addition, these child outcomes were the results of a research-based assessment tool. It may not be the desired result, but rather the results from assessing young children. By planning curriculum and activities for young children to be successful and through authentic observations and research-based assessment, we learn what the outcomes of the children’s learning and development are. We use them to change our plans or change the way we are doing things so that the children are successful.

Continuous Planning Process

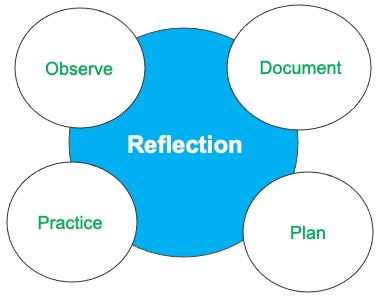

Now let’s get started on the continuous planning process and how this relates to developing a year-long curriculum guide. The planning process must be cyclical and reflective. There are always going to be four things that you are going to do.

- Observe

- Document

- Plan

- Practice

You are always going to observe the children, document your observations, plan based on your observations and your documentation, and practice. I tend to use the word practice rather than implement because we are all professional practitioners. We do not know if what we are going to do on a daily basis is actually going to be full implementation. It is better for me to think of it as we are practicing it. Just like doctors practice medicine, early childhood educators are practicing early childhood. Then, once we get through this continuous planning cycle, we are able to do assessments.

Figure 1 shows a circle that has the word reflection in the center because reflection should be in the middle of all planning, regardless if it is for activities or a year-long curriculum guide. When we go back to these four terms from the continuous planning process, we reflect and think about it, whether we are observing, documenting, planning, or practicing.

Figure 1. Diagram of curriculum and reflection during planning.

Think about it yourself right now. When you do observations in the classroom, are you simply observing something or are you observing and reflecting, so that you know what it is you are observing? When you observe children, you should not simply write down what they are doing all of the time. You need to come back to those three important steps and reflect.

You already know about how children learn and develop. You get to know individual children's abilities and where they come from. When you observe and reflect, make sure that you only document those things that are like milestones for children, those things that are what you have never seen them do before. You do not want to document performance-based observations because those are not authentic.

We want to make sure that we do not document observations in which children are doing something because they are going to get something in return, such as a sticker. For example, if someone says, okay everybody, let’s line up and see who can do this. We want to make sure that we allow the children to initiate their own activities. Then we can observe how they experience them. In other words, a child could be playing in the science area and you see them make a discovery. That would be a great observation because it might be something that you have never seen before. Also, it helps you understand whether or not the child understood it or if they are more interested in continuing their learning.

After you document, you still need to go back and reflect. We do not want to take down observations unless we are going to look back and reflect on them. We also do not want to document something that is a lower-level skill. You want to document to show that children are growing and that they are learning something new. When you reflect on your documentation, then you can plan activities that will scaffold the children's learning. We know from research that children are on a continuum of learning. They are learning and we have to reflect and plan in order to help children move from A to B. We always want to know individual children, what they know how to do, what they are unable to be able to do, and that spot in the middle where they need help doing it.

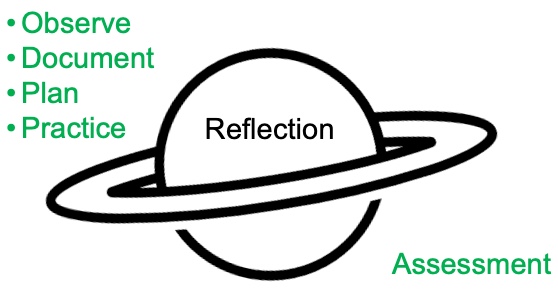

When children need help doing something, that is when we want to create plans that help them to be able to do it on their own. After we plan, we reflect again because we want to make sure that we are covering everything that we know. Then we go ahead and put our plans into practice. When we put the plans into practice, we reflect and think again and try to decide, is this practice going to work? How do we know if it is going to work? We come right back to observation. Once again, we observe and reflect, document, reflect, plan, reflect, practice, reflect, and continually keep this cycle going. Figure 2 shows another illustration that depicts how we think of the continuous planning process.

Figure 2. Illustration of the continuous planning process.

Once again, we have the circle with reflection in the middle. This illustration has an outer circle that is rotating around reflection. Think of the outer circle containing those four steps that I have been talking about, observations, documentation, planning, and practicing. Think about those constantly circulating around reflection. Teachers have to be reflecting at all times. You are not going to be able to follow a script when you are working with young children because things happen. But if you try to keep this continuous reflective planning cycle in mind, you will be able to complete children's assessments very efficiently and effectively.

A Deeper Purpose

An important piece of the planning process is planning for assessment for the children. We want to plan with a purpose because we are going to be held accountable for what children are doing and how they are growing and developing in a program. When we prepare for assessment, we try to collect observations of the children. Remember that collecting authentic observations are not the only thing that we use. Some teachers also use video recordings or voice recordings, and many will use children's work. I do not mean children's as in coloring pages or worksheets because we do not consider those developmentally appropriate. Instead, we use children's work such as something they painted, drew, or made in the writing center. Maybe they wrote a letter or a note to the teacher that could be evidence you could collect.

Then we are going to take all of this data that we have collected on the children and analyze it. From analyzing this data, we are able to plan for individual children, as they may need activities that are a little bit different from other children. We also need to be able to plan for groups of children which is very different from planning for individual children.

Your daily activities or weekly activity plans can sometimes be very complicated to others when they view them. However, to the teacher, it should look very simple because the teacher already knows that everything they are doing is based on the information they have learned about children including what they know about them, what individual children need, and so on.

Another thing to think about is reporting children's progress. We have to remember that when we collect all of this information, we have to be held accountable. Part of our accountability includes reporting out to the families or the parents, as well as to the administration. This is where we talk about child outcomes. Typically for the families, this is done through a scheduled parent-teacher conference. Sometimes teachers will call a parent in for a conference and talk about something that the teacher has a concern with or something the teacher is really amazed by and wants to know more about. Sometimes it is the parent who wants the conference.

Either way, a parent-teacher conference has to go both ways. It is not an opportunity for the teacher to report outcomes and then ask the parents if they want to give any input to the curriculum. The parents have no idea what that means. Instead, it needs to be a very well-balanced conversation. You may ask the parents specific questions about what the child likes to do when they are at home or what their favorite things are. The more that we keep that parent-teacher conference balanced between the two, the more we learn about the child, the home, and the more that we build a relationship with the family. Remember, the family or the parent is always considered the child's first teacher. We are facilitators of the children's learning, so we really need the parents and families to help us as we plan curriculum for children.

Unscripted

Keep in mind that the planning process is unscripted. This may sound a little confusing because we are talking about building a year-long curriculum guide. You are planning, but at the same time, it is unscripted because you understand there are endless windows of opportunities when you allow children time to explore, experiment, and take risks. You need to be very flexible and make the classroom a flexible environment at all times, as it should be based on children's interests. Although your plans are flexible, they should appear to be structured. You need to be able to talk about this in-depth and articulate this planning process with families and with stakeholders because it is important that they understand how children learn and what the importance of play is because play comes into everyday activities.

Improvement

Also, remember that you are always in this continuing planning process for the purpose of improvement. Improvement is continuous and it is always data-driven. From year to year, you do not have the same children. You have a new group of children every year, so you always have to use your data. It is also important to be able to articulate how we use our data to inform our practice.

Where Do We Begin?

Where do we begin to climb this big mountain of developing a year-long curriculum guide? How do we do it? First and foremost, think about the program that you are in. Does your program operate on a 10-month schedule, an 11-month schedule, or a 12-month schedule? Looking deeper, some programs that operate on 10-month schedules begin in August and end their program in May while others begin in September and end in June. Programs all across the country operate on different program years. An 11-month program might start in August and end in June. Twelve-month programs might start in August or September and some might even start in July. I want to start climbing up this mountain with just a frame. Look at the frame around the mountain in Figure 3 and take the mountain out of it, because it is not going to be a difficult task. Just look at an empty frame.

Figure 3. Framed image of a mountain.

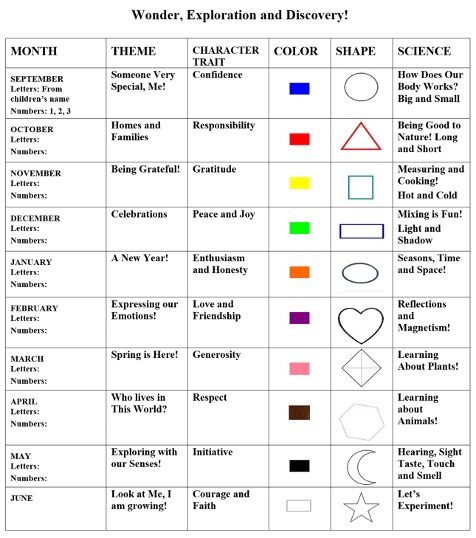

Year-at-a-Glance Chart

I think that when we envision this empty frame, we might want to think about a year-at-a-glance chart, kind of like an outline for this frame. In this year-at-a-glance chart, I would recommend including a column for basic monthly themes, character traits, learning concepts, and learning domains. These are the four components that I would recommend when you are first beginning to develop a curriculum guide.

I do want to give you a word of caution. Whatever you put into your curriculum guide is going to be interpreted by the viewer. Just like you are looking at this right now and seeing what I have on the screen, you are going to hold me accountable. My recommendation to you is, whatever you put in here, make sure it is something that you know you are going to be able to do and it will not come across as something scripted or something you will forget. Keep in mind that you always have to keep the importance of play in the back of your mind.

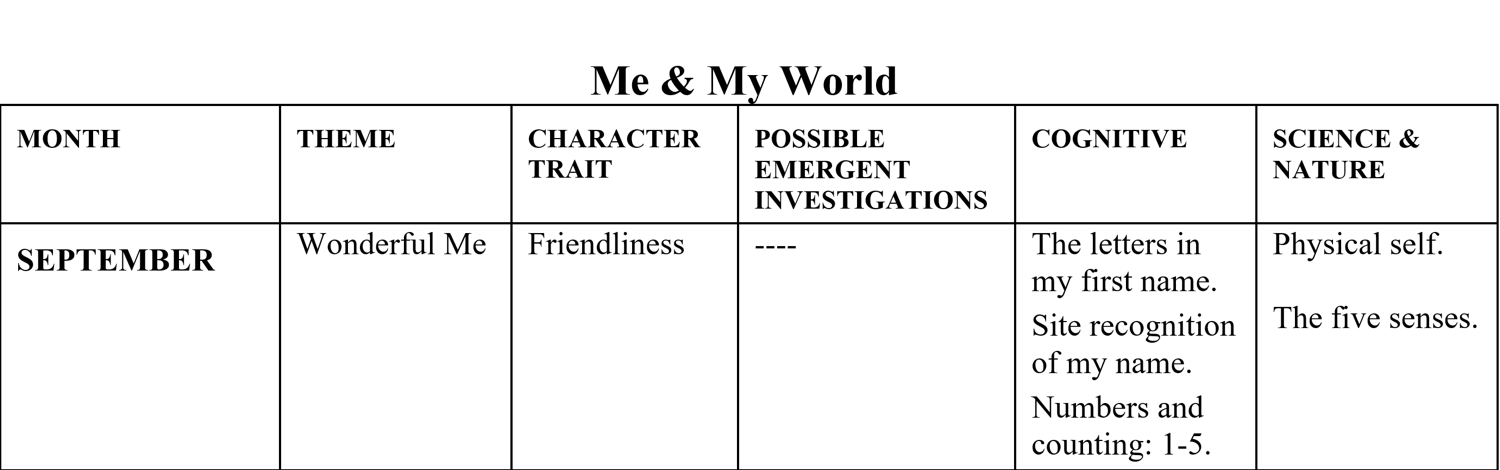

Month

Figure 4 shows an example of a year-at-a-glance chart that is very basic. This program is starting its basic chart with the month of September. At the top, you will see it says, Me and My World. I take this as meaning this program has an annual theme for it. You do not have to have an annual theme in your curriculum guide, but you may want to.

Figure 4. Simple example of a year-at-a-glance chart.

When I look at this chart and see Me and My World, I think, wow, this is a program that knows that the age and the stage of the children coming into the program. They are being honored and recognized. I see it as a program that places an emphasis on children's self-esteem and maybe even their confidence because we know from decades of research, that young children in the preschool years are egocentric. They care about themselves and their own little worlds. I think this was a good theme to have for teachers to keep in mind as they move through the year and for the parents to see.

Theme

In the column next to the month, we see the word theme. The theme here is wonderful me. Remember, wonderful me does not necessarily mean you will have theme boxes that say, wonderful me. Instead, try to focus the activities you plan on individual children and how they feel about themselves. We know from decades of research that young children are known to be ego-centric. By this, I mean they are mainly interested in themselves and their world and not the world in general and the people around them.

Character Trait

The next column is character trait, which in this example is friendliness. I find this quite interesting because this is the first month of school and some children are coming to school from another program and have already had preschool experience, but some children have never been in a preschool environment before. This month could be critical for the entire year. This month is like a foundational platform for the children to have either a very good experience or perhaps get off on the wrong foot, then you are struggling with behaviors the rest of the year. I found friendliness to be a good character trait for teachers to focus on when working with young children. This helps set the stage, so to speak.

Possible Emergent Investigations

The next column is possible emergent investigations. I like that this particular planner chose this as something that they want to have in their year-long curriculum guide. Notice there are dashes in that column and no information. This indicates the teachers and children haven’t had the opportunity to get to know one another, so this is open for observation and reflection. You may have ideas of what could go here, but remember, we do not want to put something in our guide that we are going to be held accountable for later. In the following months, you could probably predict some things to add to this column, especially if you have children in your class who are returning and you already know them.

Cognitive

The next column is cognitive. I know that a lot of parents, other adults, stakeholders, and even administrators believe that the most important part of a child's early childhood education has to do with academics, cognition, and what we are actually teaching the children to remember. We don’t teach children through rote learning we teach them through play. Having a column called cognitive lets the families know that we do have this domain that we work on but we have others as well. In this example, you see children will be working on the following:

- Letters in my first name

- Site recognition of my name

- Numbers and counting, one through five

This is quite a bit but it is not something I would worry about being able to accomplish in the first month, and here’s why. When children come to us, we know they have not learned their ABCs or understand that each letter has a purpose with its name. We have all heard the stories of parents who have one-year or two-year-old children who can recite their ABCs and according to their parents, are the smartest children in the world. Then they come to our classroom and we document activities where the children display that they do not know their ABCs. You may have parents who wonder why. They may say, I want them to learn their ABCs or they already know them, so I do not know why you would see this or why it would be different than home.

We have to be able to articulate to the families that the way we teach the alphabet is by using Developmentally Appropriate Practices (DAP). Again, with DAP, we know that a child's name is something they own, it belongs to them. They are coming into an environment of the unknown but there is one thing they do know for sure, and that is what their name is. They enjoy sharing their name and they enjoy asking others, what's your name? They like name games. If this particular teacher is going to teach the alphabet, she will likely begin with the first letter in their name. That becomes very meaningful to the children. Then they can start to write their name on their artwork or on other things.

The next one was site recognition of my name. By that, I mean learning to see their name in print with proper lettering. The first letter is capitalized and the following letters are in lower case. This should be displayed to children in places such as their cubby, something that is being presented in the classroom on the wall, or on a job chart. Once the teacher consistently uses the printed name of each child written in the proper format, the child learns to recognize it by sight. They may not be able to write it that way, but they can recognize it by sight.

The next thing is numbers and counting. We know children love numbers and counting. In this case, they are focusing on the numbers one through five. These are fairly easy numbers to learn in the first month because they can be attached to playing games. Notice that when we are talking about numbers and counting, it is just that, numbers and counting. It does not include one-to-one correspondence, at least not in the first month of school. Children might count things, but they could not tell you that there are five pencils on the table. These are examples of cognitive skills to teach that we can be held accountable for and know they are developmentally appropriate.

Science and Nature

The last column is science and nature. I know a lot of preschool teachers often say, I never liked science. They may have a science area in their classroom and it just has some pine cones, magnifiers, and maybe a balancing scale with counting bears or something, but science and nature are not just about those things. It is about the children actually having ideas and having a sense of wonder.

In this example, they have included physical self and the five senses. I think that this is an important column to include, especially now that we know that today's education programs are focusing more on STEM and STEAM. I think in the early years we can go ahead and bring this into the fold of things. Children are going to be learning about wonderful me, including their physical self, or bodies. They can learn it through hokey-pokey and other games. Then we have the five senses. They are not going to learn the five senses in the way that they need five senses to do different things. Instead, they are going to know that they use their nose to smell, ears to hear, etc.

Detailed Year-Long Curriculum Guide

Figure 4 showed a very simple chart to illustrate what the first month might look like. Now I want to take you from a simple chart to one that is the start of a year-long curriculum guide. It is going to be far more detailed. Take a look at the example in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Example of a detailed year-long curriculum guide.

Let’s start at the top with the title, “Wonder, Exploration, and Discovery.” These three words have one thing in common. I wonder if you know what that is. Let’s stop and think for a moment about what these words mean - wonder, exploration, and discovery.

These three words have one word in common, unknown. I find this to be an awesome thing for a program to use in planning their year-long curriculum guide because it is about the unknown. We really don’t know what will be coming in the future. The first row underneath the theme shows the month, theme, and character trait like the other example, but they have added color, shape, and science.

Month

Under the first column of month, this program starts in September. Under the month they list the letters and numbers they want to focus on that month. For September, they said the letters are going to be from the child's first name, so the first letter of the first name, and they will focus on the numbers, one, two, three. These are very simple and easy to practice because oftentimes, very young children like to say things like one, two, three, go. Children may be familiar with those numbers, so the teacher can teach a little deeper as they go through the month.

Theme

The theme for this month is, someone very special, me. Once again, this being the first month of the year for the children, this is what they are focused on.

Character Trait

The next column is color. I know that a lot of programs do not have to place an emphasis on teaching colors. I also know that many states have assessment tools that do not include colors, but as early childhood educators, we know children love colors and we know that children love to play color games. An example would be when children are being transitioned from one activity to another teachers may say, if you are wearing blue you can go wash your hands. The children will look all over themselves trying to find the color blue. Some of them will even find just one little, tiny little speck of blue, but they know blue. I enjoy using colors in a curriculum guide and recommend that if you are going to use colors, begin with the primary colors.

Shape

The next one is shape. In this example, the focus is on learning about a circle. I like this as an example because when children are born, the very first shape they associate is the mother's face. The face is close to a circle so I think that is a good place to start. However, many programs have reason to use other shapes or no shapes at all.

Science

Under science in this example, you see how the body works and big and small. Once again, how the body works has everything to do with the theme, someone very special, me. It is all about them. The children are concerned about themselves and what they can do. There are so many songs and games they can play. Big and small is a good concept to help children learn about size. This column would be a reflection of implementing STEM and STEAM into your program.

Before we move on, I want to remind you not to think that this guide is scripted. It is not a script. It is very open-ended and flexible. If you look in the first column under the months, you will notice from October to June the teachers or the program haven't even identified what letters or numbers they will work on. This will be determined as the teachers and children get to know one another and teachers have had time to observe and assess.

With the other columns, they pretty much know that in October after they spend a lot of time talking about the children and who they are, they can then start talking about homes and families. They can start talking about responsibility and taking care of toys and so on and so forth, then moving all the way down.

- What is known about how children learn and develop?

- What is known about individual children in regard to their abilities and interests?

- What is known about the society and the culture they come from?

Year-Long Curriculum Guide

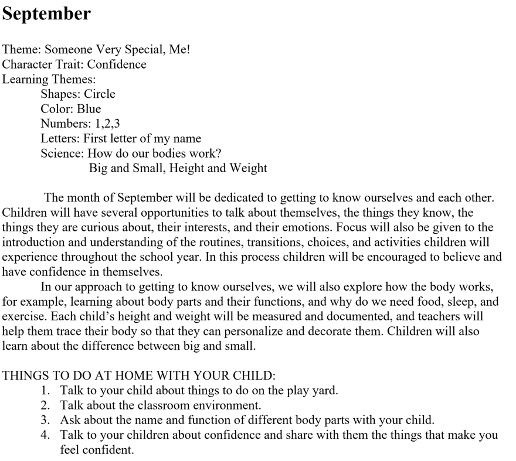

I like to follow the year-at-a-glance chart to make the year-long curriculum guide. You may not want to have this year-at-a-glance chart in front of you when you create a year-long guide, but I like it because it is a quick view of the year. Now we are going to create pages for each month that will let parents know what we will be doing.

Figure 6 shows an example of a year-long curriculum guide for the first month, September. When I have created a curriculum guide in the past, I have used a chart similar to the one in Figure 5 first, then I used these monthly pages.

Figure 6. Example of year-long curriculum guide for September.

Think of it like a wall calendar, where you may see a picture on the top, and then at the bottom, you see the calendar format. For example, you could put September at the top, as seen in Figure 6, and the bottom could be your calendar. You could plug in dates for activities for the school or dates if the school is closed or for parent-teacher conferences so people can plan ahead. You can see here that the very first section of Figure 6 comes directly out of the year-at-a-glance chart. This includes the theme, character trait, and learning themes. This information is followed by two paragraphs describing what will be done in the month of September.

The month of September will be dedicated to getting to know ourselves and each other. Children will have several opportunities to talk about themselves, the things they know, the things they are curious about, their interests, and their emotions. Focus will also be given to the introduction and understanding of the routines, transitions, choices, and activities children will experience throughout the year. In this process, children will be encouraged to believe to have competence in themselves.

In our approach to getting to know ourselves, we will also explore how the body works, for example, learning about body parts and their functions, and why do we need food, sleep, and exercise. Each child’s height and weight will be measured and documented, and teachers will help them trace their bodies so that they can personalize and decorate them. Children will also learn about the difference between big and small.

At the bottom of this example, there is a list of things to do at home with your child. This is a great way to engage families in the curriculum. The first one is talk to your child about things to do on the play yard. Oftentimes parents will just say, what did you learn today? The children have no idea what they are talking about. But when you give them an example of what to talk to their children about, that builds communication between the parent and the child. It also helps at parent-teacher conference time when you can ask the parents, were you able to try any of these things?

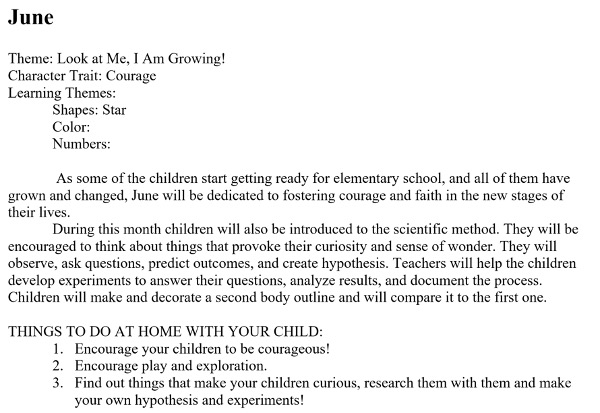

Figure 7 shows an example of a year-long curriculum guide for June. You can see that it is laid out the same as Figure 6 for September. The narratives are a little bit shorter, but it still follows a very professional-looking format for parents, staff, administrators, and stakeholders. You will need to create one of these for each month of your program. Hopefully, you can see how to plan your curriculum for the year and still maintain the emergent curriculum approach.

Figure 7. Example of year-long curriculum guide for June.

Closing

A textbook by Beaver, Wyatt, and Jackman says, “Themes, units, projects, and curriculum webs will aid you in developing a child-centered emergent curriculum approach.” We have talked about themes and how you can use units. You can create your own webs and projects, but it all is still emergent. I hope that you can see that in following this planning process that I have described, your curriculum approach remains emergent. It is not prescriptive. It provides a sense of purpose, a sense of structure, and it does help those who use the guide to be successful.

References

Beaver, N., Wyatt, S., Jackman, H. (2018). Early education curriculum, a child’s connection to the world, 7th ed. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Hendrick, J., Weissman, P. (2011). Totally learning, developmental curriculum for the young child, 8th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education Inc.

Kostelnik, M., Soderman, A., Whiren, A., Rupiper, M. (2019). Developmentally appropriate curriculum, best practices in early childhood education, 7th ed. Pearson, Inc.

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/planning Accessed May 18, 2021.

Citation

Fairfield, R. (2021). Developing a yearlong curriculum guide. Continued.com - Early Childhood Education, Article 23736. Available at www.continued.com/early-childhood-education