Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Documentation: Making Children's Learning Visible, presented by Hilary Seitz, PhD.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Identify and explain the multiple purposes of documentation.

- Summarize ways to use documentation in the classroom for both individual children and for a group of children.

- Describe tools and ways to create documentation that makes children's learning visible.

Introduction and Overview

Documentation is a journey that I have been on for a number of years. I've been exploring different ways to document and make children's learning visible.

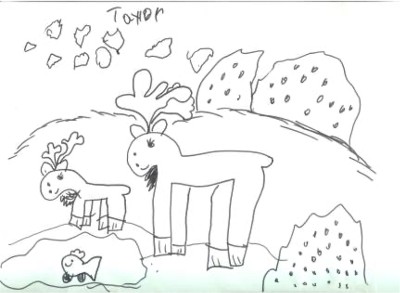

Figure 1. Work sample - drawing of moose and her written name from Taylor, age 4 years, 2 months.

Figure 1 shows a drawing from a four-year-old when she had just moved to Alaska. She was excited about seeing moose and talked about moose all the time. She was asked to draw moose. You can see with her excitement and eagerness she was able to capture many details whereas some of her other work didn't show all those same details. I'm going to show you how we can help children show everything that they're excited about as they demonstrate and provide evidence that they are learning.

I would like to begin with an introduction about who I am as an early educator. I began my journey when I was still growing up and I didn't even know that I wanted to be an early educator. I always gravitated towards children and I think part of the reason is I just would observe them and notice things, and so children always gravitated towards me. As I moved into it, I realized that this was my field. I could go in and see children, and I could make an understanding about why they were doing things in ways other people couldn't do. Part of that was because I was documenting things, taking photographs, and writing observations. This was a story I began telling about my own journey without knowing it was my journey. As I did this and learned more, I continued to want to know more about it so I started going to school. I tried working with different-aged children. I worked with infants and toddlers all the way up through fifth grade and taught reading. I realized that was not what I wanted to do. My heart was with preschool age, but really the whole early childhood field from birth to age eight.

Documentation tells your story. My story shifted and it had lots of different turns. Part of that was because I was a child who grew up in a lot of different places. When you have that experience, that means you experience a lot of different backgrounds, different cultural things that happened, different traditions, and different areas of the country. I was fortunate.

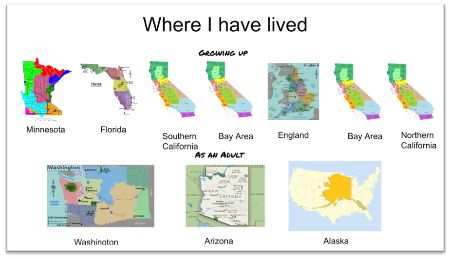

Figure 2. Map of where Hilary lived growing up and as an adult.

In my early life, I lived in Minnesota, Florida, Southern California, Northern California, and then all the way to England in Europe. As you can see in figure 2, I went back and forth. As an adult and as an educator, I taught in Washington, Arizona, Alaska, and California as well. That's an example of how you can use documentation just to tell a timeline story. I will share many other ways to do documentation.

What is Documentation?

The first question is, what is documentation? Documentation is an interesting word because it's used in different ways. When some hear the word documentation, they might think, "Oh I know, it's panels, or it might just be taking notes on something, or it might mean doing an observation." Documentation sometimes has different connotations depending on your setting.

Take a moment and imagine a child sitting on a rug in the middle of a classroom. There are wood shelves with buckets of toys surrounding the small rug. You can hear other children playing, talking, and laughing. Think about what you saw in your mind. Did you notice little things about that child playing? Did you notice their facial expressions? Were they really serious and looking deeply at their toys, or were they tentative to join in with other children, maybe sitting off by themselves? Were they excited and leading the crowd and telling other children what to do? Were they using their right hand or their left hand to pick up the toys? Did you notice different types of toys and how the child interacted with them? Did you notice or hear any conversations about their play? Did you see how the classroom supports various areas of development and curriculum? Did the classroom inspire creativity and inquiry for this particular child? Do you think they could be successful?

When you do this type of deep thinking about an individual child and then think about the classroom, the environment, and the other children, how could you document those things to tell that story? Learning to see, to observe, to expect, and to know all the different things going on and document this learning is what documentation is. It takes practice to really see what you're doing. It's the small details that help you be a good documenter and assess children's learning to make it visible.

Documentation is a way to share and communicate a story. It might be a visual story, an auditory story, or an electronic story, but it's a way to communicate that story. It's a way to learn and to communicate information about a particular child. You're going to learn about how your curriculum is happening in your classroom. It also gives you feedback as a teacher and makes you be very intentional. Documentation is learning how to see. Good documentation will help you see things, but it also helps others see them too. The photo in figure 3 can be used to tell several stories if you look carefully.

Figure 3. Girl using a rolling pin.

A photo might tell the story of development. When I look at figure 3, it looks like she is right-hand dominant. When she begins to write, she's going to be writing with her right hand. I can see that because I can see the palm of her hand pressing deeper on the right side and it's shaped differently. That is a very minor detail if we look at just both of those things, but it is important information that will help us when we think about writing. I'm only showing her hands here, but if we had a video, series of photographs, or a series of notes taken about this, we might know other children are in the area. Maybe she's not looking down at what she's doing at all, maybe she's looking at another child and talking, or maybe she is really serious and trying really hard to make it flat. Maybe she is making dinner and she's making the pancakes right now. We don't know, but we're seeing little tidbits of the story. Just one photograph can tell us a lot of information.

Why Should I Document?

This is a really important question, and I'm going to go through a number of different reasons.

- Celebrating children

- Providing evidence of learning

- Family accountability – family connections

- Child understanding

- Child development (assessment & curriculum planning)

- Curriculum understanding

- Documentation cycle

- Reflective practice

The first reason is it celebrates the children you're working with. We have a lot of different children in our programs and classrooms and it helps to celebrate all of them. It will provide evidence that all of these children in your learning community are learning together. I like using that word. It's evidence because that gives it some structure. I'll go into more detail about what each of these looks like.

It also helps support family accountability. I'm sure you've all had that parent that comes in and says, "Oh, I think my child is ready to read" or, "How come they're not doing this?" This is a way to show accountability that they are learning to read. Just by thinking of that prior picture, we are seeing that that child is right-hand dominant and that we can focus now on seeing how she's using a writing tool. It helps us provide accountability to families of why we're doing those things.

It helps us understand individual children. Documenting helps us think about child development, and where they are with all the different areas of development including how we assess them, how we plan our own curriculum, and how we think about the larger holistic view of our classroom. If we understand what is going on and we have that evidence to show that they already have done these things, then it helps us understand and become that intentional teacher. Then it helps us think about this whole process as a cycle. Once you can start thinking about documentation as a whole cycle, you truly are that reflective practitioner and intentional teacher.

Celebrating Children

Celebrating children is important because every child is unique, every child is capable, every child has strengths, and they're all going to be different. If we just assume all two-year-olds are going to play outside for the same length of time or all three-year-olds are going to want to ride the trikes, or all four-year-olds can write their name, then we're actually missing a lot of the details. Each individual child has different strengths. Maybe some three-year-olds are all outside looking at the trikes, but some of them might be looking at them with an interest from the corner. Some might be sitting on it and using their feet. Some might actually be pedaling. Some might be pushing. They're all having the same experience but looking at it from a different perspective that's based on their own prior experience, their personalities, and different types of materials in their environment.

There are a lot of different things that impact how individual children connect to an experience. When we connect to these individual pieces of a child, it helps celebrate the individual families and their cultures. It helps us honor them. I love using that word because it's honoring the specialness of each child.

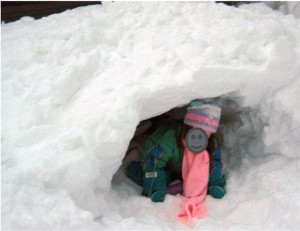

Figure 4. Child playing in the snow.

Figure 4 shows one of my favorite photos of this child playing in the snow in Alaska. This child did not really like to play in the snow very much. She would get all dressed up and get her mittens on and by the time she got outside, she decided she didn't want to be there anymore. She would often sit by a teacher and hold their hand or just walk around. We later learned there were some other reasons why that might've happened, but the day that she decided to crawl into the snow cave, it was like a big celebration. We took photos and her mother was shocked that she actually was crawling on the snow, touching snow, and becoming part of the children's play outside because that was a first for her and the mother hadn't seen that. That documentation celebrated her individual differences and it still honored that she wanted to play alone. She still looks a little tentative like she's not sure she likes it, but she was actually trying it. It's showing that and we're celebrating that. If we had a series of pictures of all the children playing together, it could also celebrate what this group of children can do.

Providing Evidence of Learning

Another reason we need to document is to provide evidence of learning. Some programs, such as a kindergarten program, have report cards, portfolios, or tests. Those are types of artifacts that do provide evidence of learning, at least for the test makers or for the teacher, perhaps, if they are meeting standards, but there are other ways to document to provide that evidence of learning.

We can take photographs of children. We can write observations, write comments about them, take videos of them, and provide evidence that we are meeting those standards. In many preschool classes or in a Head Start classroom, even in some kindergarten classrooms, they have some book handling skills. As part of the standards, children need to understand which side they opened the book from, is it from left to right or right to left? Where are the words? Can we tell if the words are on the top or on the bottom?

Figure 5. Children looking at a book.

Figure 5 shows a toddler that already has some book handling skills. If we were to just ask a toddler to open the book, we might not be able to see that, but we might be able to capture it. I love this too because it helps us understand the learning experience. In figure 5 the toddler is working with an infant and she is modeling how to do those things for the infant. Now, while these may not be part of the standards for an infant, she is starting to gather those foundational pieces.

When we have these types of photographs that provide evidence of meeting standards, it helps us understand the learning experience better. Sometimes, we read what's in an early learning guideline or in the common core and we want to make sure our students are meeting those guidelines by understanding and doing the things listed. That also helps us as educators understand the value of it and the importance of doing those things.

Another type of evidence is work sampling, which is sometimes artwork that shows creativity and can show other types of things. I like to use other types of work samples as well that may show more evidence of learning. For instance, in my classroom, we used to start with a writing sample at the beginning of the year. We would have a variety of writing materials out such as pencils, markers, and different types of paper. We could then gather some work samples. Or you might ask them, "Please write your name." If you do that same type of work sample three or four times throughout the year, you're going to gather information that will provide evidence of growth and learning. These work samples, photographs, or observations are also authentic, which is really really important.

Authentic assessment means it's something real, tangible, and in context. For instance, in figure 5 of the two children reading, I can see their interest in books. I can see they have some book handling skills. It's a real thing instead of just a checklist that says, "Yep, met the book handling skills," which might not give that same information. When looking at evidence of learning we want to think about the different audiences that we are working with. We have a lot of different audiences when we do documentation. If I were to post this photo on my wall with a little typed blurb about it, such as making connections between pictures and words, then the children would see themselves and that the evidence is honoring them. It's going back to celebrating children and helping them see that what they do is important. "My teacher thought it was important. So, now I might want to read another book."

Family Accountability and Family Connections

It also helps families and administrators understand what you're doing in your program and classroom. When you document, you are making family-school connections. Just as I said with that photo on the wall, maybe a family member walks in and says, "Oh my gosh, there's my child. Oh, yes. She loves to read." Now all of a sudden, I'm going to be learning more things about that particular child. I'm going to know that the parent is excited about it. I might follow up with, "Oh, what's her favorite book at home?" or some other questions. That helps create a family engagement opportunity in my classroom.

Anyone who's a parent knows that anytime you see your own child's face on something, you get excited. There are different ways we can facilitate this as we celebrate children. Maybe it's on a bulletin board, a panel, a newsletter, or even a social media post. I know, even for my own children, when I would see them in their classroom doing something and it was posted, I would always get really excited and I'd share it with my mom, and then she would share with her friends. It fosters family engagement and creates a joint experience. It's a way to demonstrate that pride in children's learning, but it also helps create that family-school partnership and make that much stronger.

Child Understanding

I said this briefly, but when you post a photo on the wall of children doing things, children are one of the audiences for documentation. We sometimes forget that because sometimes we think, "Okay, we've got to collect all this stuff. I've got to document all these different developmental areas because I need to put it in the portfolio and I have to turn them in." Or, "It's on this app and it says I have to do that today." But having children use your documentation helps them understand the routines, their expectations, things that are going on in their classroom, and revisit experiences.

Remember, a child who is three, four, five, even seven or eight doesn't have the same prior experiences we have. Let's say you took the class to the zoo and learned about elephants. That might be the only time they've ever seen an elephant. Maybe they've seen an elephant in a book, but that might only be two different experiences with an elephant. Posting a photo in the classroom of the elephant or a photo of the children with the elephant helps them relive that experience. Now, they're having their third experience with that elephant. It's helping children understand and remember so that they can build on it further.

Documentation also helps children ask more questions and go deeper into what the experience was because the first time they saw the elephant at the zoo they might have been overwhelmed or even a little scared so they backed up. We know when a child is fearful, their adrenaline increases, and they have many different things happening inside their brain. But then when you take some time in a calm environment later, you can think deeper. This happens for us as adults too. As you're taking in a new experience for the first time you may be overwhelmed and not fully able to experience the situation. But when you revisit it a second time, you have a different sense and a prior knowledge of the experience. Now, as you revisit it you can ask a new question.

This is a way for children to go deeper in their thinking and help them communicate what is happening with each other. It is a powerful tool because it helps children rethink it and share their ideas, which may help other children understand better. If you think about child development knowledge, Vygotsky says, "You learn more sometimes from your peers." Having your documentation up and available for children helps them take their learning deeper.

Child Development (Assessment and Curriculum Planning)

Another reason to document is to learn about child development, a child's learning, and growth. There are several apps available to help us document and some curricula have different tools that go with them. Many of them are focused on the child's growth and development. The areas of development include physical development, or large/gross motor and small/fine motor, cognitive, communication, and social-emotional development. You might even think, "I'm going to do an individual snapshot of every child in my classroom to look at their social and emotional growth this week." Sometimes you use the areas of development to drive how you document.

I like to do this in the first week of school and look at who the child sits next to, who they play with and talk with, and if they talk with adults more than children. Those are all social-emotional things. I like to get snapshots of every child at the very beginning of the school year because by the second or third week if I go to do the same thing, I might start to see some patterns. I might start to see that the child now plays with the same group of friends, or that they're with different people every single time, or maybe they played by themselves. Again, I'm going to get that developmental information about their social-emotional health.

A really good way to do some quick assessments is to get a list of every child and pick an area and say, "I'm doing it this whole week." The other thing to do if you have multiple adults in your classroom is to have both of you do the same task because you tend to focus differently than other people focus. It's really fascinating to do this. I was a very shy, quiet child and I tended to find one or two friends and I'd stick with them. Now when I watch children, I tend to gravitate towards looking for children that have some of those same behavioral patterns that I had as a child. If you were very outgoing, you might focus on those children. Some people focus more on boys, some people focus more on girls, some are better at focusing on outdoor play or indoor play, or different areas of the room. Having a different person look at the same child's growth area and then having a conversation about it shows a well-rounded form of child development and learning in terms of an assessment. That type of documentation is really valuable.

Looking at the developmental milestones is another way. The first way was looking at the developmental areas, but looking at milestones, such as learning to walk, takes it a step further. In my classes at the university, I often teach motor development first and we start looking at both fine motor and large motor. I love to have them do this in the infant-toddler class because children are just learning to walk and their bodies are so interesting. It always makes me think of a video clip where you have a bunch of toddlers learning to walk in one space and they all try to stand up in a different way. You may think about your own child or the children you work with. When children go to stand up, are they bending at the knee? Are they bending at the ankle? How are they balancing themselves? Really look at how a child learns to stand up or how they accomplish other milestones too.

It might not be a physical milestone. Sometimes it might be a cognitive milestone of learning to read. If you can capture a child learning to read and create a video of that to put in your e-portfolio, the child's family is going to think you are the best, most brilliant teacher ever. It's actually very easy. The first thing is to figure out what milestones you want to document. If you know you want to watch them learn to walk or watch them learn to read you have to think through, "How does my environment support this? When is this going to happen? Am I going to watch after lunch or am I going to watch during reading time when other children are reading? Am I going to pull them aside at a different time and just work one-on-one?" You're going to have to do some planning to get these milestones captured.

If you really think through that and capture it, you can string photos together with commentary or narrative or have an actual video of children learning to use the sounds, then learning to string words together, then actually reading a book with sight words of mixing these different concepts together. By the end when they actually can read a whole book on their own, you'll feel a sense of accomplishment in yourself by putting all those things together. Documenting milestones can be really important.

Lastly, use this type of assessment to show the growth of a child over the whole year. I like to use portfolio assessment to do this. I used to use notebooks where you just collect items such as those I've mentioned, and more I will share, such as work samples, observation notes, photographs, et cetera. Now, I've been using some online tools to create these e-portfolios that are amazing. It's almost like creating a personal portfolio for a child. These types of tools will show growth. They will show how a child progresses and what children are learning. You are making that learning visible to any of the audiences you're creating it for.

I've been talking about using documentation for individual children, but you can use it to understand your own classroom better. When you document for your whole classroom, it will make your teaching so much better and it will make what you teach connect better with children. You'll have far fewer behavioral issues. You'll have a lot more interest in different types of experiences. If you use documentation, even children that don't necessarily want to go to the art area or another area may begin going there. If you are using documentation intentionally, you can use it to help children want to do things that they didn't even know they wanted to do. Sometimes, just thinking about what is going on in your environment will help guide that too. We have to be really strong observers so that we can use that to advise our own lesson planning. When we do this, it will provide evidence of meeting all of those standards that our administrators or principals want us to do.

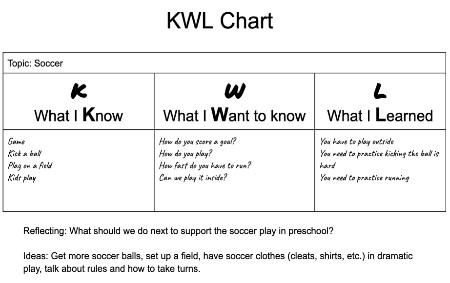

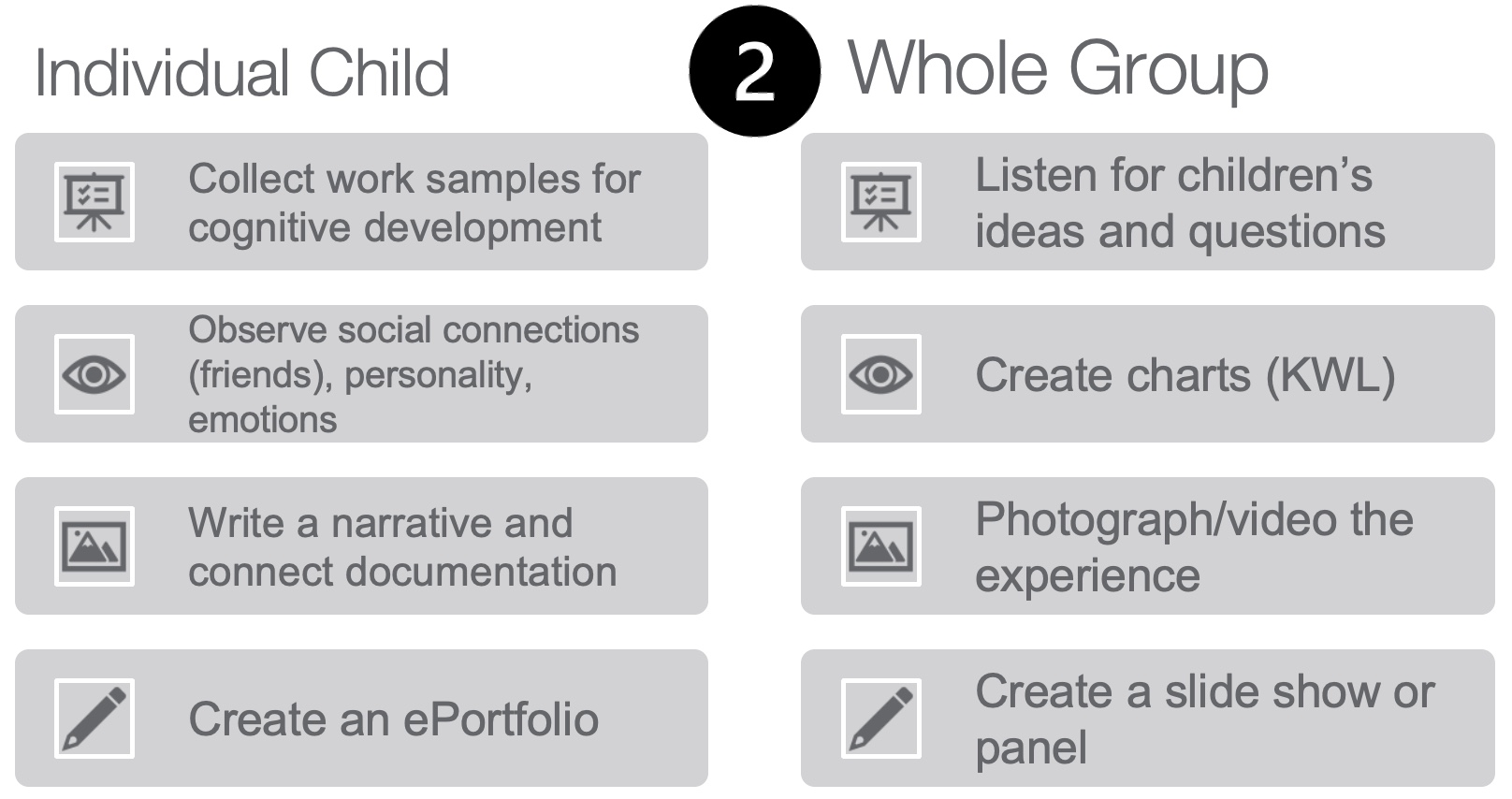

Here is an example. I live in Alaska right now, and while this probably happens anywhere you live, the first day we have snow it doesn't matter what I've planned to do in my classroom. Every child wants to go outside and play in the snow. Use those opportunities that come up and then document them. Planning lessons is one way to do that and using this KWL chart is another way. A KWL chart looks at what you Know, what you Want to know, and what you Learned.

Figure 6. KWL chart on soccer.

Figure 6 shows an example of a KWL chart on soccer. You can use this with anything. I could put in snow here and do this with children. The K stands for what I know. I chose the idea of soccer because I was with my nephews and niece the other day and they are five and six. Two of them are twins. They just cannot get enough of soccer and that's all they talk about. They wanted to know more about soccer. I finally sat down with them and they had some other friends over. This was not actually in a classroom, but you can do this with small groups, whether you're in a classroom, school program, or anywhere else.

I asked them, "What do you know about soccer?" They were very excited and said, "Oh, it's a game," and they all started shouting out different things at me. It's fun to do this in a large group in a classroom too. These are some of the things they told me. "Well, you get to kick a ball, and you play on a field, and kids play." My first thinking was, "Oh, great. Okay, there are five or six kids here. I'm going to make sure I have five or six balls for them so that they each can play soccer." In terms of development, I know they all are going to want their own ball. They surprised me. They did not want to play with five or six balls because there were five children there and they all wanted one ball because they knew when you play a game of soccer, you only play with one ball. You're not allowed to have two balls on that field. They already have some prior knowledge. You want to figure out what that prior knowledge is. Sometimes, you might have to change it or you might have to rethink or redirect sometimes, but they gave me those four things.

"It's a game, we kick a ball, we play on a field, and it's for kids to play." I thought, "Well, I know some adults that play." All of a sudden, all these different things came into my head. Then I asked them, "Well, what else do you want to know about soccer?" That's what the W stands for. I do this big visual either on a whiteboard or giant chart paper. I would create this chart and we'd start with the K. Depending on the group you're working with, either at the same time, later that day, or the next day, ask them, "What do you want to know about this? What do you want to know about soccer?" They told me, "Well, we want to know how to score a goal." They also wanted to know how to play the game. They know how they're playing, but they know there are also rules. Remember, a five and a six-year-old are starting to understand games with rules. They know there are some rules and asked how you play it.

They also wanted to know how fast you have to run because one of them said, "You had to keep running fast." Then they wanted to know if they could play it inside that day. I didn't answer these questions as they were asking them. Instead, I recorded them so they could see that. At that moment I was celebrating and honoring their ideas. In my own head, I was also thinking, "How could I tie this to the developmental standards and other things we're doing? How could I add this?" I know they were very excited.

I could imagine having this exact conversation with the group of children I once had in my classroom. We did have a similar one about bikes, and we came up with rules, a bike course, and other different ideas. That is what's driving your curriculum. That is what's driving you to become an intentional teacher. You start thinking about, where are they are at? Where do I want them to go in terms of their development and learning? How am I going to document all this? How am I going to change my curriculum so it's intentional to meet their needs?

When I did this with the bike project in our classroom, the children became fascinated with bikes. We started taking bikes apart inside our classroom. We noticed that there were patterns on the tire wheel. Some children used clay to make imprints of the tire prints. Then we started looking for textures in lots of things. It grew into many other things. That bike project lasted over a month. It wasn't on our curriculum plan. It was in our afternoon choice time, but that was their favorite time of the day. They wanted to do that bike project. Not every child did every bike activity every day, but some did. Every child did something with the bike project. It created a sense of excitement for the children to learn. Then we documented all of their learning during the bike project by putting up the photographs of them taking the bike apart. One child noticed there was a nut and bolt loose on one of the bikes, and then they started checking all of them. We ended up taking apart a bike and trying to put it back together. We had the handlebars put on upside down and had to fix that. It was a great project and the children and parents were so excited. Parents started coming in to see what we were doing, we had videos of our activities, and we set up a little bike meet where everybody got to bring their bikes and we made sure they were all safe. There are a lot of different areas that can be covered with a KWL chart and project.

Let me get back to the soccer example. The chart in figure 6 is an abbreviated chart from what I did with the children. The next day I asked, "So, what did you learn?" They learned several things including you have to play outside because I told them they couldn't play soccer where we were at. Then they told me, "You need to practice kicking the ball." They tried kicking it but many times they kept missing. We talked about how sometimes you have to practice something and it could be hard. They decided it was hard, but some of the time they got really good. They also noticed that sometimes one leg kicked the ball farther than the other leg. They started noticing all these different things. They also noticed that they needed to practice running so we started practicing running and would time them as they ran from here to the other side. They really enjoyed this and it helped drive the curriculum.

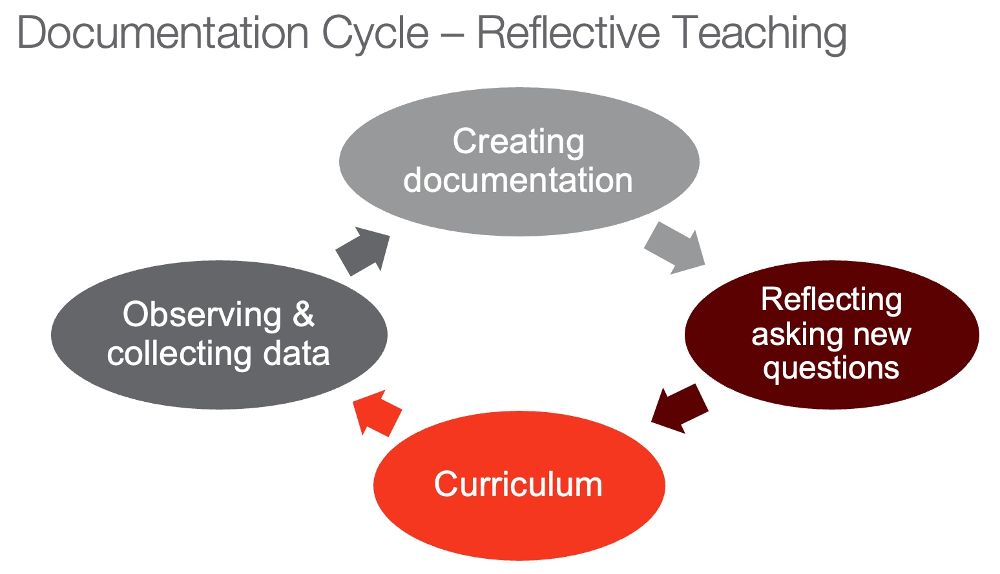

Documentation Cycle - Reflective Teaching/Practice

As I said in the beginning, documentation has many different meanings. When I hear the word document or documentation, I immediately think about a cycle. I'm observing kids and seeing what they're interested in. It could be soccer, snow, or the bike project. When I see that interest, am observing for milestones, or looking specifically at an area of development I have to figure out what exactly I'm observing and collect as much data as I can. Documentation is a cycle that includes observing and collecting data, creating documentation, reflecting and asking new questions, and adapting the curriculum based on the knowledge you've learned. Figure 7 shows this cycle of documenting and reflecting on your teaching. What I was showing you in figure 6 is part of the documentation cycle.

Figure 7. Documentation cycle.

If you have another person collecting data too, you start to see different things. Once you get all of that, you're going to create something and I'm going to go into that in this next portion. You're going to use all of this to help you create documentation. When you create it, it will help you reflect and ask more questions. As you start putting your documentation together you're going to start noticing patterns. For example, "I noticed Johnny always has that soccer ball and I noticed Susie is always in the same area but she never has the ball. I think she might want it. I'm not sure, but I think I'm going to follow up and ask if she would like to learn to play soccer too."

We're going to start using that documentation to help us ask new questions. We might be asking questions about development. Maybe I want to see how children can use more phonemic awareness in my classroom and I want to see how they're using books and letters. If I'm not seeing any evidence of phonemic awareness in any of the documentation I've collected and I want to see some of that, I might start with some small group experiences so I can start having conversations. I'm going to reflect and ask my own questions, which will depend on what I was observing.

Last, documentation is going to change my curriculum. I am going to be using a curriculum that meets individual and whole group child interests and needs, and that is what a reflective teacher does. Getting back to this idea of reflective practice, it is that higher-level teacher I think everybody strives for. When I was teaching in my public preschool classroom I worked with parents a lot, just as many of you do. This program was similar to what a Head Start program is. Parents were expected to participate. At the beginning of the year, none of the parents knew each other. None of them really understood why we have Play-Doh, why we have time to go play on those chalkboards, or why we have family-style meals in our classroom. They weren't necessarily opposed to it, but they didn't understand the value or the importance of those things.

If we get to this higher level of reflective practice, we're doing this in collaboration with our whole school community, meaning the children, parents, and teachers. This could also include others in your community. One activity we did was after school. I started taking photographs and printing them out. I would share them after school, have my clipboard of notes, and we would start looking at all of these things and say, "Hey, what are you all seeing?" The children would relive the experience and say, "Hey mom, look, I did this!" or, "I want to try this again when I get home." The parents were seeing, "Oh, wow! I didn't realize you could do that when you were exploring rocks or." Doing that helps us understand where the children have been and it gives us ideas of where to go. Again, it's driving my curriculum development, but it's also getting a lot of buy-in from families. Now they want to be a part of this experience and by the end of the year, we would have so many families volunteering in our classroom we had almost as many adults as children. We had to manage that in a different way because you don't want too many people in the room. Think about how to get to the level where you have families engaged and everyone is really thinking about the learning of these children.

Two Reasons to Document

Why should I document? These are the real reasons that I've been coming back to throughout this course. The first reason is to understand individual child growth and learning and to make it visible. The second reason is to look at group learning and make our curriculum visible. If we go back and think again about all of those different aspects of why you should document (to celebrate children, to provide evidence of learning, etc.), these are the two reasons: we want to understand individuals and we want to understand the group. Developmentally appropriate practice goes back to typical development, what a group of children that are four years old does and what an individual child does. Also think about how the different cultural impacts, prior experiences, environments, and other things shape it? That's why we document.

Think back now to all these different ways we've talked about documenting and think about which of those resonates with you. Is it to honor children, celebrate what they're doing, and have children see that? Is it to provide evidence of learning? Is that what's super important in your program right now? "I need to prove to our administrators we are doing it. That's why we're making noise." I once had a principal who was so concerned with noise that I had to show him why talking was so valuable. We were learning language acquisition, among many other things, but all they seemed to care about was we were too loud. Is it to provide evidence of that?

Is it to build family and community partnerships? That's another really important thing. Is that why you're documenting? Maybe we want to get more families involved so that they can help us in the classroom. Is it so I can understand individual child learning and growth? Is it because I need to get portfolios because that's what my work says I have to do? I've got to collect this data and evidence and I've got to assess where they're at. So, I've got to get on top of that. Maybe I want to do it because I have a lot of assessments that I'm required to do.

Think about it and ask yourself, "Is that my purpose?" Maybe your purpose is just to rethink your curriculum. "I want to make my curriculum more meaningful to children. I'm having a lot of behavioral guidance engagement issues, maybe children aren't even interested, so I need to document what they're doing and think about why they're not interested. I want to start seeing what they are interested in. I might want to use this new cycle to help me do curriculum planning. I'm going to start using this in terms of getting to the next level of my curriculum planning or maybe I want to become that reflective practitioner. I want to be really thoughtful and intentional about every single thing I do."

If you think about these they're sort of on a continuum. It's like when you are that intentional reflective practitioner, you're already doing all those other things that I mentioned. Sometimes you're not excellent in one of those in another area you're working on. Maybe you're not as great at connecting with families and that's going to be an area you're going to think about. You might do documentation to help include them. You might think, "I really want to get better and I'm taking a child development class. I want to think about what development looks like for these three-year-olds I'm working with?"

What Should I Document?

When documenting individual child learning there are several things to look at and document, but I don't recommend doing all of these things the first time. Choose one or two of the following items to collect. You might choose one of these options per week.

- Child's work samples

- Individual child growth and development observations

- Evidence of meeting standards

- Child's questions and ideas

If you want to start looking at group learning, focus on one of the following items to document.

- Experiences

- Expected behaviors

- Projects

- Evidence of meeting standards

- Children's work

- Curriculum ideas or experiences

- Families and relationships

- Children's, teachers', and parents' inquiries

An experience happening in the class might be that somebody is bringing in their new pet rabbit and we're all going to share that today. I'm going to watch how all the children interact with a pet rabbit. It might be mealtime and I just want to see how children do with family-style meals. Pick an experience and start observing that as a whole group. It's a very holistic view. You're not focusing on individuals per se, you're looking at the whole experience of family-style meals. Maybe you're going to collect writing samples for the whole class and then lay them all out and think, "Wow, half of these children know how to write their names and the other half are still just doing little squiggles for words. Maybe I need to rethink how I'm teaching them to write their names and write letters."

Think about children's work samples. Again, not on an individual child basis, but as a collective or as a whole. Maybe I'm looking at a behavior. "I've noticed that transitions after lunch are really rough in my classroom. Maybe I'll spend some time observing what happens during this time. I could turn on a video camera to observe and document what happens during that time." I might notice that a couple of children are really tired and maybe a couple are getting moody because they're tired and others are getting more excited and more energized. Sometimes, when children get overtired, their energy level changes. So, I might look for behavioral things.

I might use a curriculum idea or an experience. Again, a video works great to do this. If I lead a group time with a group of children, I might video that and then listen to their ideas and their experiences. When I'm leading a group, I hear different things and notice different things when I rewatch it. Another option is to have a teaching assistant, a parent, or somebody else document it for you. A project, such as the bike project I discussed, is great to focus on doing KWL charts to document what is done by the group. I love to do that and then create a class book or a class PowerPoint that loops and children can watch it. Sometimes I focus on families and relationships and how they're a part of our curriculum. Other times I want to make sure our whole group understands certain vocabulary. This helps show that we are meeting that core knowledge or that early learning guideline. I also want to be able to address all the other teachers, parents, and others' inquiries.

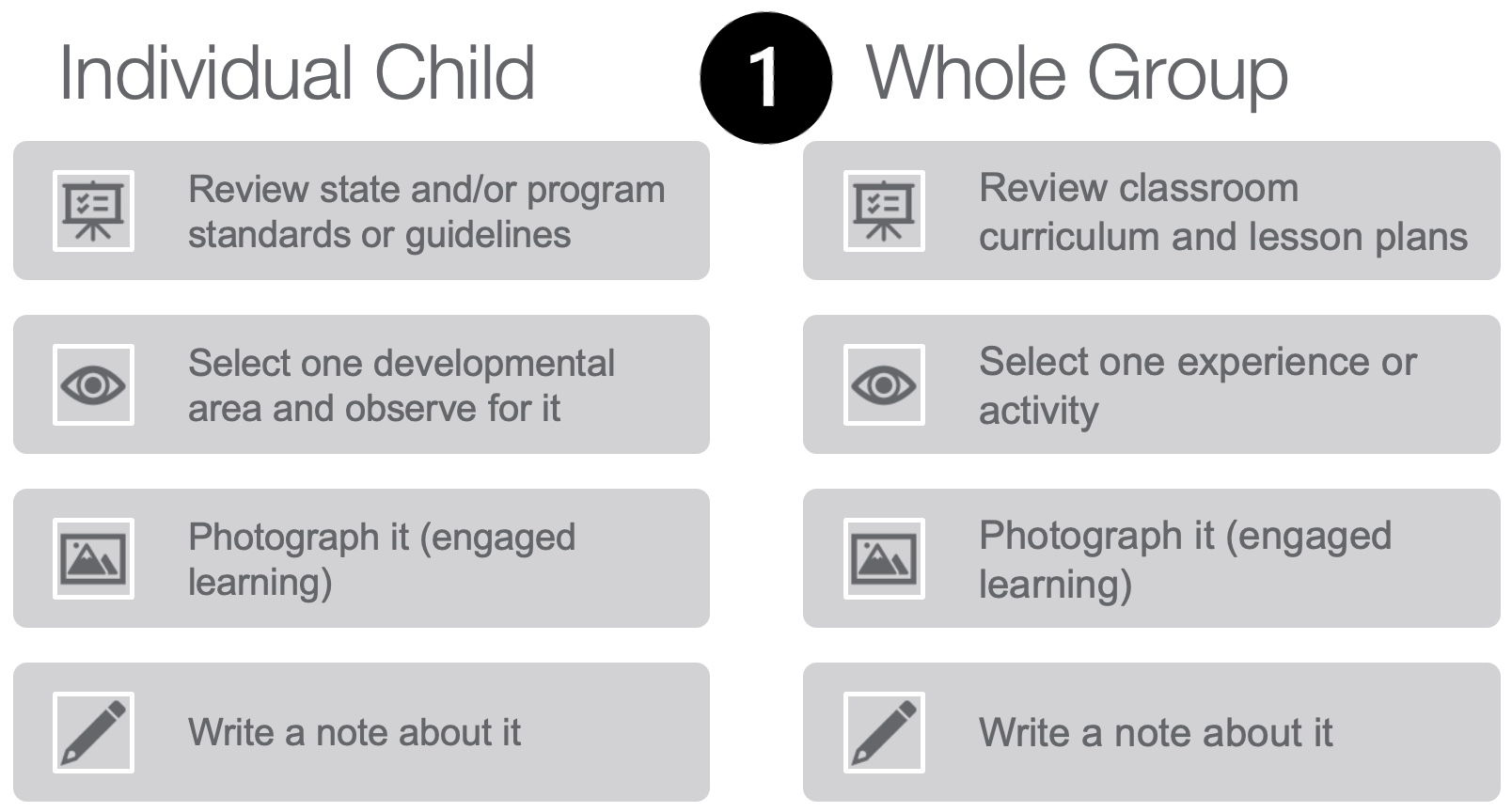

How Should I Document

If you're going to document, there are two levels to think about: individual child and whole group. Figure 8 shows steps one and two for documenting for the individual child and the whole group.

Figure 8. How to document for the individual child and whole group.

For step one, when I start with the individual child, I'm going to review all of my early learning guidelines and expectations for them, and then I'm probably going to just select one area of development. I'm going to photograph it and then I'm going to write a note, something simple. That's my first step when I decide I'm going to document for individuals. If I'm going to document for the whole group, I'm going to use step one of figure 8 to determine what I'm going to document. Then I'm going to review it and look at my curriculum lesson plans to see if it matches. I'm going to just observe that one experience or activity, photograph or video it, then write a note about it. I'm going to be very concrete and explicit about what I'm doing.

Step two for the individual child involves collecting the work samples. I'm going to do this over a few days or if it's the name samples, I might do it over a few months. But I'm going to just focus on that developmental area and collect multiple things. I'm going to start observing for multiple things and then I'm going to write notes that go with all of the things that I collect. Then I'm going to create an e-portfolio for that child, but I'm going to be very aware of all the things I just entered into it. It's very intentional. I'm not just throwing in all their art projects and finger painting. Those are important, but I want to be very intentional so that what I collect is providing evidence and showing child growth. It can include arts. I teach creativity in the arts, so that is one of my favorite things. But I try to use that very intentionally to teach language and literacy through the arts or to teach social-emotional development through music. I might show a clip of music, but it's going to show how it connects to cognitive development or another area. That's the next layer. Using art examples in the e-portfolio can be amazing.

During step two for the whole group, we're listening for multiple children's ideas, recording all of these things, creating KWL charts, photographing and videoing the experience, and then putting them all together in either a slideshow, such as Google Slides or PowerPoint, or creating panels in our room. We are making that learning visible to the whole group, to our families, and all the different audiences that we work with.

Items Needed to Document

When you document, there are certain tools that will make it easier for you. These include pens, paper, clipboards, digital cameras (smartphone, iPad, or another device that captures photo, video, and audio), computers, printers, and a system for storage, such as the cloud. Different types of products create different types of artifacts. The e-portfolio is similar to an artist's portfolio or can be a notebook that has different sections in it. If I do a paper version in a notebook, I like to start by using tabs to separate the notebook into the areas of development including cognitive development, motor development, et cetera. Sometimes I'll use tabs to differentiate projects the child has done. Pick your topics and then start inserting things. The e-portfolio is great and there are a number of different tools you can use online. I've even been doing these with my college students and we make our own learning visible. We are documenting our learning and I have them create it. But in a sense, they are learning how to do it for children by doing it on themselves.

You might've heard of panels. These are similar to the old-fashioned bulletin board, but a panel is very intentional. It tells a story and is not just putting up everybody's finger painting. It would be intentional. It might only have two people's finger painting papers, but it's going to tell the story of why these two are important, what they are doing, and how this provides evidence of what the child is doing. For example, maybe it's motor development and we are all using our pointer fingers because we are learning to write letters in the finger paint. Whatever it is, your panel tells your story. It's not for every single child. It's going to tell the story of a concept.

You might use videos. Again, you're not playing a whole video. You're choosing elements of videos to include and to incorporate that would show evidence of learning. It might only be a 30-second video of having a child learn to read. It's going to be something small, but intentional.

The bulletin board is still important. It's similar to the panel, but it might just be a collective place. I love to do child bulletin boards where they get to celebrate and put up things they are proud of. That's another way to reframe what they are doing. I also like to use frames to show work. I go to the thrift store and get a whole bunch of those big wood frames, take out whatever's in the inside, and let children put pieces of artwork in it. Then I have children tell me why they put that in there. They can tell their story and you can put their words inside the frame with their piece of artwork or their work sample.

Figure 7. Example of documentation.

Figure 7 is another type of documentation that is similar to what a panel is, but it's just a simpler way. We went outside and collected different types of leaves during the fall and then put them on a piece of butcher paper. We compared the leaves and noticed there were all kinds of leaves. The children put their names in the chart by their leaves and we had all kinds of conversations. We then turned that into a KWL chart. This was actually the project of a student I was observing. She did a fabulous job and connected the activity to the different early learning guidelines in our state. Alaska Early Learning Guideline 34 is children demonstrate knowledge of numbers and counting. That includes children sorting objects and then counting and comparing them. It also includes sorting objects by one attribute into two or more groups (big, medium, and small). This documentation provided evidence of the children learning those things.

What are the Stages of a Documenter?

As I've mentioned, you can't do everything at one time. Here are the stages of a documenter.

- Stage 1: I want to document

- Stage 2: Exploration of my tools

- Stage 3: Focus on children – learning to observe

- Stage 4: Information gathering

- Stage 5: Connections: telling the story

- Stage 6: Documentation for decision-making

The first stage is deciding that you want to be a documenter and figuring out how to do it. I've just given you all a bunch of different ways to do that. That's the first step. The second step is to explore what tools you have in your classroom. Do you have pens and pencils and other things I discussed in the last section? When I go observe my students, some of their centers or programs require them to wear aprons. They may not be aesthetically pleasing, but they're very handy because they keep notepads and note pens in their pockets. They can keep a phone to take photographs. The phone is not to text, but to take photographs and do recordings. It's important to have those items easily accessible. Then you have to decide what type of documentation you're going to do and what you need to do that.

Stage three is learning how to really observe and focus on the children. Think about what you are observing, how it's important, what you are doing, and why you want to collect the information. What is the overall focus of my observation? Is it child development and growth or is it a project? You might find it's easier for you to just do one area of development instead of multiple areas.

Stage four is information gathering and collecting all the documentation you have. Think back to when I spoke about the families coming into the classroom and seeing what the children had been doing. We were looking at all the different information that had been gathered. Then we continued on to stage five, where we told the story using a panel, an e-portfolio, a poster, or a class book. Tell your story with your documentation.

Lastly, you are a professional teacher. You're using your documentation for decision-making. Going through these stages takes time and practice. Just like in the KWL chart where the children realized in order to play soccer they needed to practice running and kicking the ball. You need to practice collecting these items and practice figuring out what they actually mean and connecting them to your evidence.

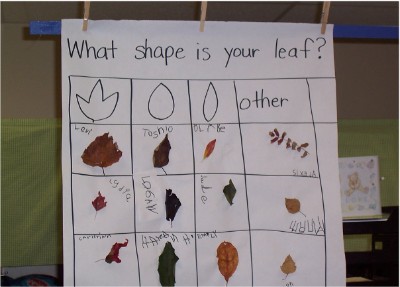

Figure 8. Young boy on playground equipment.

Let's make learning visible. Take a moment and look at figure 8. Look at this picture of the individual child and then think about these questions in your head.

- What do you see?

- What areas of development?

- What type of environment?

- After you write your observations, what will you do with them?

- Why is this observation important?

Write those different observations down and then think about what story would you tell with these? Why would this observation be important? Other than it's an adorable child running, what is valuable about this?

Conclusion

In conclusion, documentation is a really powerful tool. You can do so many things and address different audiences. You can make your story and the children's story valued, celebrated, and honored. Documentation can be used for individual children or whole groups of children and in different combinations of that. Documentation makes your own teaching more intentional. There are many tools you can use to document learning, but documentation takes practice. It takes a lot of time and energy. It's going to take support from others around you. If you're doing it all on your own, it's going to be that much harder. It will be better and easier if you work as a team with others, but ultimately, documentation makes children's learning visible.

References

Citation

Seitz, H. (2021). Documentation: Making children's learning visible. Continued.com - Early Childhood Education, Article 23768. Available at www.continued.com/early-childhood-education