Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD) - Impact on Children and Families, presented by Dan Dubovsky, MSW.

Learning Outcomes

As a result of this course, participants will be able to:

- Explain the term fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

- List 3 brain structures that are damaged by prenatal alcohol exposure.

- Explain why it is important to know what is causing a behavior.

Introduction

Knowing what is causing a behavior is one of the most essential pieces for anyone working with children, adolescents, or adults. My son, Bill, was diagnosed with fetal alcohol syndrome at age 19 and it is because of him that I am involved in this field. When Bill was about seven years old I took him to a neurologist to try to find out why he was having some of the problems he was having. He didn't do well in school. Often we have this idea that individuals need to fail at something in order to get more of what they need. So he was put in a regular class even though he needed a small class. He failed in that and was put in a small special education class. A small special education class with acting out children is probably the worst class for a child with an FASD because the child will model the behavior of the other kids in the class and act out more. A better classroom is one that's mixed with some pro-social kids so they can model more positive behavior. One of the things that we learned is that those with an FASD tend to learn most by modeling the behavior of those around them. Not by being told what to do, not by being shown what to do, and not by being consequenced for not doing it, but modeling. It is so important to keep that in mind. Bill didn't do well in school, he didn't do well in the neighborhood, and the thing that got me to recognize there was a real problem was he wasn't responding to my amazing parenting techniques. So there had to be something wrong with him, of course. The neurologist did a cursory neurological examination, and she said, "Does he drink?" I said, "No, I don't think so. I hope not, he's only seven. Why would you ask me if he drinks?" She said, "Well, his reflexes are uneven and usually that's indicative of drug or alcohol use in an individual, or in their parents." That was in 1982. There was very little I could find out about this. For the next seven years, we really struggled. He started to gather diagnoses like attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, reactive attachment disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder. None of the treatments for those diagnoses seemed to work, so he was labeled as being noncompliant, uncooperative, resistant, manipulative, and unmotivated, or what I call NURMU. None of those treatments worked, of course, because they were the wrong diagnoses. Then when he was about 19 years old, he got the diagnosis of fetal alcohol syndrome.

Figure 1. Dan's son, Bill.

The reason for his behaviors and understanding his behaviors began to make sense when he was about 15. A book was published called The Broken Chord by Michael Dorris. Michael had adopted a child from the Midwest. He had lots of trouble raising his son and couldn't figure out why his son had all the problems he was having. He went back to the community from which he adopted his son and they began to talk with him about fetal alcohol syndrome because they knew there were a number of people who were affected. It was the first popular book on FAS. A lot of people have read the book and said it was very depressing because Michael just talked about all of the problems with his son and none of the joys. I read the book and I said, "Ooh, this is Bill. Ooh, this is Bill. This sounds just like Bill." His behaviors finally began to make sense. One of the things which really hit me from one of the stories in the book, is that as Bill got older into adolescence I would come home from work, he would be nowhere to be found, and the door to our house would be wide open. We didn't live in a neighborhood where that was a good idea, so I would say to him, "Bill, every time you leave the house you have to lock the door. Every time you leave the house you have to lock the door." I would come home from work. He would be nowhere around. The door would be unlocked. He would come home, and I would consequence him for it, because with a diagnosis of ADHD, reactive attachment disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder at that time, clearly his behavior was all willful and purposeful and I needed to consequence him because that's also what the professionals had been telling me. Having been a mental health clinician for so many years that's what I would do anyway. But that didn't seem to work. Finally, after months, we would go to take the garbage out and come back into the house and the door would be locked. It was like this is just an obnoxious adolescent getting back at me because I've been punishing him. We would go into the backyard, come to get back in the house, and the door would be locked. It looked like such willful, purposeful behavior, but what I understood from some stories in the book and also from the diagnosis as I learned more about it, was that he finally got it that he had to lock the door whenever he left the house, but couldn't figure out when he was just outside taking the garbage out or in the backyard he didn't need to lock it, but when he was a block away he did. The part of the brain that's responsible for figuring out what to do in a specific situation, like when do you lock it and when don't you, is damaged by prenatal alcohol. So again, what looked like willful behavior was absolutely not. Of course, I had the wrong approach by consequencing him for it, because it wasn't purposeful, willful behavior. So I really thank Bill, because he really taught me to think differently about people. I look back at the people who I worked with, especially as a therapist, who would come into my office and put their head down, pull their coat or their hat over their face and I would write in their chart poor eye contact or not motivated for treatment, not recognizing that some of them couldn't tolerate the fluorescent lights in my office. Fluorescent lights are really tough for many individuals with an FASD. The lights are too bright. They hear the buzzing in the lights. They see the flickering in the lights. They can't articulate it, but a child may crawl under the desk or put their head down or run around or disrupt their room or run out of the room and will never think oh, could it be the light that's bothering them?

Then I think of some of the families I worked with where I gave them a list of instructions of what they needed to do when they took their loved one home for a visit, and they wouldn't follow through. I would write that they were neglectful, uncaring, or sabotaging treatment, not recognizing that I was setting some of them up to fail by giving them a whole list of instructions. You can't give somebody with an FASD a list of instructions, even if you write it down, and expect that they will be able to follow through with five, six, seven, or eight instructions. So again, what looks like willful, purposeful behavior from families may not be. That's really a key. So I thank Bill for that. I also use a picture of him because nobody would see him in their program, in their area, or meet him on the street and say, "This is a young man with this disability." For the most part, this is a hidden disability that nobody recognizes. If people know a little bit about fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, they know about fetal alcohol syndrome. They think if they don't see somebody who is short in stature with certain facial features and maybe a small head size, they're not seeing the effects of prenatal exposure and that's not it at all. So again, Bill is the one who really got me to think about this. So I've been involved in FASD now for about 35 years.

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD)

- FASD is a spectrum of disorders.

- There is a wide range of intellectual capabilities in individuals with an FASD.

- There is a wide range of disabilities due to prenatal alcohol exposure, from mild to severe.

- There is no way to predict how much alcohol will cause how much damage in any individual.

- There are many different ways that the disabilities of FASD are manifested.

The term fetal alcohol spectrum disorders or FASD is a term that was coined about 17 or 18 years ago by a group of people who got together because they wanted to convey the idea that this is a true spectrum from mild deficits all the way to fetal death and everything in-between. Somebody may just have had problems with math in school. Somebody may have difficulty in social situations that may be due to prenatal alcohol exposure. They may be on the mild end of the spectrum. The other end of the spectrum is fetal death. For example, every obstetrician should be asking every woman who had a miscarriage, especially in the second trimester of pregnancy, how much she was drinking because we know that alcohol exposure, especially in the second trimester, can increase the risk of miscarriage. I know women who have had multiple miscarriages whose obstetricians never talked with them about the fact that alcohol use may have caused that. Fetal death is the other end of the spectrum, and there's everything in-between. Not everybody with a fetal alcohol spectrum disorder has the same difficulties to the same degree. Also, not everybody prenatally exposed to alcohol has a fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, but we can't predict who will and who will not ahead of time. So again, the term fetal alcohol spectrum disorder is a descriptive term to convey that range of effects due to prenatal alcohol exposure.

- Behavior often appears to be purposeful.

- Typical approaches to “difficult” behaviors often don’t work.

- Many individuals with an FASD have other difficulties.

- One cannot categorically say that all behavior is due to the FASD.

- Not all children prenatally exposed to alcohol have an FASD, but the spectrum of FASD causes brain damage.

As I said with Bill, the behaviors that we see look very willful and purposeful, but the typical approaches like rewards and consequences are not effective in helping resolve the behaviors. My belief is that if a consequence doesn't help change the behavior, it's probably not the right approach. In many situations, if the person is extremely willful, we either have to find a more serious consequence or find a more motivating reward. We find what a child likes to do and does well and we take that away for bad behavior and we use it as a reward for good behavior. My feeling is we should not be doing that. Across the spectrum of FASD from mild to severe, we see brain damage, and that's really key. The brain damage has nothing to do with intelligence. It's really important to know that people have been identified with an IQ over 140, which is genius level, who still can't follow three directions at once, who still can't read social cues, and who still don't act appropriately in social situations. This is not because they're purposeful and willful in their behavior, but because of how their brain is working. Brain damage just means that certain structures of the brain are not working the way they should. It doesn't mean that there's a low IQ. People often connect brain damage with low IQ and we should not be doing that.

Incidence and Prevalence of FASD

- The range of FASD is more common than disorders such as Autism and Down Syndrome

- Generally accepted incidence of FASD in North America has been 1 in 100 live births

- Recent studies are identifying a prevalence of between 2.4% and 4.8% (1 in 50 to 1 in 20)

- Much higher percentage in systems of care

- Majority undiagnosed

An article was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association a couple of months ago with some updated prevalence rates (May et al., 2018). For active surveillance studies in the United States, it's still somewhere between 1.2% and 5%. But the weighted prevalence is as high as about 9.8%. So we're looking at an average of one in 20 to one in 50 individuals in the overall population having an FASD and it may even be higher than that. In our systems of care, early education, early intervention, special education, mental health treatment, and a number of other systems of care, we're going to see much higher rates than that. The majority of those with an FASD are not going to be diagnosed. Some of them may be misdiagnosed because our diagnostic capacity in the country is minuscule everywhere compared to this possible prevalence. The most recent studies are pretty exciting in terms of really reinforcing the idea that the prevalence is much higher than most people expect. It's much higher than most people expect because still, about 50% of pregnancies are unplanned, and most women don't know when they're first pregnant.

Roles for Early Childhood Education

- Identifying a possible FASD in young children

- Educating families on how best to support their child with a possible FASD

- Referring the child for an assessment and diagnostic evaluation

- Educating providers on what children and families affected by FASD need

- Recognizing family members who may be affected

- Identifying women at risk of an alcohol-exposed pregnancy

- Helping address the prevention of alcohol-exposed pregnancies

- Speaking with families about the importance of abstaining from alcohol

- Throughout one’s pregnancy

- If trying to get pregnant

- If planning on getting pregnant

- If a woman has been in a situation where she might be pregnant

- Speaking with families about the importance of abstaining from alcohol

In terms of early childhood education, I think that there are very, very important roles in this. One is being able to identify a possible FASD in children. There are studies that have shown that the earlier we identify this and recognize it the better the long-term outcomes. It's important to recognize it early on when a young child just doesn't seem to get it. Notice that the typical approaches aren't working and there might be something else going on here. The earlier we can recognize that the better. We can then educate families in terms of how to support their child who may have an FASD and help families recognize that their child's behaviors are typically not willful and purposeful. These kids are at such a high risk for abuse and trauma because they're such difficult children to raise. They don't eat well and they don't sleep well. Over 50% have significant sleep disturbances. Many are seen as very picky eaters. But it's not picky eaters, it's really a sensory issue. They don't get along in school. They don't get along at home. They take things that don't belong to them. They make up stories. Children with an FASD are very difficult kids to parent even when parents have no issues of their own. But helping parents understand the behaviors can help reduce the risk for abuse and trauma. Ideally, if we suspect a possible FASD, the child can be referred for an assessment and diagnostic evaluation. We can also educate other providers on what is most helpful for these children and families. Another essential component is recognizing family members who may be affected. If you're working in early childhood education, and you're meeting with a family and you're talking about all kinds of things and you're giving them instructions of what they need to do and they're not following through, it might not be that they are neglectful and uncaring. It really may be that they can't take in that information, especially verbally. Even though FASD is not genetically transmitted as we understand it now, we know that alcohol use runs in families. As a therapist, I've done many family diagrams over the years. We often identified four to six generations of alcohol use in the family. It wasn't necessarily alcoholism. FASD does not just occur in families with alcoholism. It also occurs in families where there's a social drinker who doesn't drink at all during the week and has a very responsible job. She might kick back with friends and go to the bar on Friday night and have a couple of Long Island Iced Teas, go to a party on Saturday and have a couple of martinis, and doesn't drink at all Sunday. If she may be pregnant, that can cause damage to the fetus.

Recognizing family members who might have an FASD means we need to modify what we do with the family. We can't give them a lot of verbal information, such as seven instructions all at once. We need to give instructions one at a time. You can also identify women who may be at risk of an alcohol-exposed pregnancy, and help convey the idea that the only proven safe amount of alcohol to use during pregnancy is none. Help them understand that there is no way to predict how much alcohol will be safe for any specific individual if there is any. Nobody can argue with that, because there is no proof that a drink a day will not cause any damage for anybody, for example, or even a drink once in a while. In addition, what is considered one drink for one person may be different for someone else. It's important to identify women at risk, including women who are pregnant or at risk of getting pregnant. Since you're dealing with their children, and they're still of childbearing age it's important for you to be able to talk about and share information about what we're learning about. This includes the effects of alcohol on a fetus, and that the effects begin long before women know that they're even pregnant. You can do this by speaking with families about the importance of abstaining from alcohol throughout their pregnancy. If they're trying to get pregnant, if they're planning on getting pregnant, or if they've been in a situation where they might have gotten pregnant, which means they've had unprotected sex, they shouldn't be drinking until they're sure that they're not pregnant. That's really the key. The planning on getting pregnant and trying to get pregnant is because if you're really trying to get pregnant or planning on it, then you're not sure when you're gonna get pregnant. As I said, the effects of alcohol begin so early in pregnancy. This is not willful, purposeful behavior to harm a child. No woman drinks during her pregnancy to give birth to a child with fetal alcohol syndrome. There is still a lot of stigma around this that we have to get through.

Rationale for Identifying an FASD

- If we don’t identify individuals with FASD, they often experience

- Many moves as children

- Repeated abuse and trauma

- Failure in typical education, parenting, treatment, justice, vocational, and housing approaches

- Think they are “bad” or “stupid”

- High risk of being homeless, in jail, or dead as they get older

Everybody working in early childhood education has very important roles in recognizing this and intervening differently. So many of the individuals I've seen over the years who have an FASD have for years been consequenced for things over and over again. If we don't identify them, then often they're moved from place to place to place as children either within the family or outside the family. I remember hearing about one young man at about 14 years old who was in his 27th foster home. Maybe they've lived with their birth parents for a while, then they've lived with their grandparents where the grandparents are raising them. Maybe then it was an aunt and uncle. Maybe they went into foster care. It's not unusual to see a child with an FASD who has been in multiple different foster homes, especially if we are not training foster parents in understanding that these kids are different than their birth children. They are often different than other foster children that they've had. We suspect that there are very high rates of FASD in foster care because birth parents have difficulty taking care of these kids. As I said before, they are at high risk for repeated abuse and trauma. In addition to the difficulty raising them, they tend to have no stranger anxiety and put themselves at risk. They don't recognize dangerous situations, so a child may ride his bike into a street, get hit by a car, and suffer more trauma on top of the FASD. They might get into fights, get beaten on the head, suffer more trauma, and more abuse. They are at high risk for abuse and trauma, especially when we don't recognize it because then it looks like their behavior's all willful. They fail with our typical approaches because our typical approaches are based on verbal receptive language processing, which is often really impaired. This is in everything including parenting, education, treatment, justice, housing, vocational, and every other system. Also, because they don't understand cause and effect, they don't tend to respond to reward and consequence. Remember, I said that not everybody with an FASD is the same. There may be some who respond to reward and consequence. The majority don't. But they don't understand why they're not getting the rewards. For example, "You can't go out today because you got into a fight in school," or "You didn't do your homework, or this happened, so you can't get your treat because you disrupted the classroom." Whatever it is, they don't understand it. Because they don't understand it, the only understanding they have is they must be either bad or stupid. Those are the terms that they use. A lot of the people I have met who have gotten the diagnosis say, "At least now I know I'm not just stupid" or "At least now I know I'm not just bad." That's what they thought of themselves for years and that's why it's important to recognize this early so we can break that negative self-image that begins to develop very, very early on in life when we don't recognize FASD. They're at high risk as they get older of ending up repeatedly homeless, repeatedly in jail, or dead. These are all really important reasons for why we need to identify FASD when children are young.

How Outcomes Can Be Improved by Recognizing an FASD

- The individual is seen as having a disability

- Frustration and anger are reduced by recognizing behavior is due to brain damage

- Abuse and trauma can be decreased or avoided

- Approaches can be modified

- Diagnoses can be questioned

There are physicians who have said, "Well, there's no reason to diagnose this because there's nothing we can do." That's not true. There is no cure for FASD, but there's a tremendous amount we can do if we recognize it. If we do recognize it, then we see the person as having a disability which can reduce frustration and anger on the part of families and on the part of providers if we can begin to realize that the behavior may be because of how the brain is working. We can reduce the abuse and trauma because we can begin to recognize that children with an FASD don't recognize dangerous people and dangerous situations. We have to help them avoid those situations. We can address the sleep issues, we can address the eating issues, and reduce that abuse and trauma, and begin to modify what we do. As they get a little bit older, we might question some of those diagnoses like ADHD, reactive attachment disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and ask is this truly a co-occurring disorder, or is this a misdiagnosis? Although the behaviors look similar for these different diagnoses, the approach to treating them is very different.

Challenges in Recognizing FASD

- Recognizing an FASD challenges the basic tenets of treatment and interactions with people

- That people need to take responsibility for their actions

- That people learn by experiencing the consequences of their actions

- That people are in control of their behavior

- That enabling and fostering dependency are to be avoided

- A person has to learn to do things on her or his own because that’s the real world

- Our values and biases may come into play

- About behaviors

- About drinking during pregnancy

- It may bring up issues in our own lives

- It means re-examining our practices

- It is easier to view the person as having the responsibility to change

- Equality is easier than fairness (equity)

Having worked in the field for a long time, I've really struggled with why is it so difficult for us to accept the impact of FASD on all of our systems? I believe it is because it challenges the basic tenets of everything we have been taught as parents and as professionals, including the idea that people need to take responsibility for their actions and learn by experiencing the consequences of their actions. That's the basis of every reward and consequence approach. As I said, that works for some people, but it doesn't work for most people with an FASD. It's hard to give up the idea that not everybody learns by experiencing the consequences. For some people, experiencing the consequences puts them at risk of ending up homeless, in jail, or dead. The idea that if they take responsibility for their actions and experience the consequences then they will learn doesn't work with everyone. We also think that when people are in control of their behavior they can choose to do the right thing when they want to.

So with Bill, for example, for years and years, I was told, "When we find the right motivating factor, what he really wants to do, then he will do what we want him to do in order to get it." That never worked. The response was always, "Well, obviously he's not really motivated to do that." An example I'll give you is when he got to middle school he had trouble bringing his homework assignments home. Often these kids really like elementary school and preschool because they're pretty routine. They have one teacher and get to know the routine and they feel comfortable with it. They get to middle school and have five different teachers, five different sets of assignments, and five different rooms they have to get to with the right papers. They're expected to be more responsible because they're older and they're expected to get the right books and papers in the right class at the right time. It's overwhelming for them. Bill had trouble bringing his homework home. At the same time, he was going to karate classes. He loved karate and once you signed up for karate you could go as many times a week as you wanted. So I said to him, "Bill, every day you bring your homework home you get to go to karate that night." From that day forward he never brought his homework home and never got to go to karate again. That was a mistake. He should have gone to karate every night, no matter what happened in school. We have to stop connecting school and home so much in terms of consequences. It wasn't that he wasn't motivated to go to karate. It was that there were the other issues in bringing the assignments home that had nothing to do with willful, purposeful behavior. So it's not always that when we find the right motivating factor they'll do what they need to do, and if they don't do it it's because they're not really motivated. That's not true for many of these individuals. Again, if we let that go it means that we have to change what we do.

We also think that if we do something for somebody or with them that we're just fostering dependency, and that's bad. So if you sit down with a parent and you actually make an appointment for them to take their child for a psychological evaluation and arrange for somebody to take them to the psychological evaluation or another type of appointment, then you are fostering dependency. If you just give them the phone number or the appointment card and if they're really motivated then they will do it and follow through, and if they don't follow through, then they're being neglectful. It doesn't work that way. Fostering dependency is a really good thing because people need to feel that they have a safety net and that they know who they can count on in order to move forward. Many people believe that everybody needs to learn to do everything on their own because that's the real world. However, when they're in receiving our services they need our help and we should be able to provide that for them. This may challenge some of our biases and our values about behaviors and seeing all behaviors as purposeful and willful. If we learn that a parent has been drinking during pregnancy, many people still have this stigma and they blame the mother. We have to break through that stigma. Birth mothers should never be blamed for this because it's not willful behavior to harm their child. It may bring up issues in our own lives. I've done many trainings over the years where people have come and talked about the fact that either they believe that they have a child with an FASD or that they themselves may have an FASD. A lot of people don't want to even address that. I think these are all reasons why we're not getting the recognition of FASD and the funding that it needs. We don't get nearly the funding and recognition of FASD that we do for autism, and FASD is more common than autism. However, autism doesn't have that stigma, and with FASD we're still fighting that stigma. It also means if we recognize FASD we have to change what we do. It's easier to do what we've learned with everybody, and it's easier to say that this child or adult has to change. When they are ready, then they'll respond to what we have to offer. As opposed to maybe we need to change what we have to offer.

We also think that we need to treat everybody the same in order to be fair. We've kind of interchanged those two terms, but being equal and being fair is not the same thing. If we treat everybody the same, then we couldn't possibly be fair to everybody, because everybody is dealing with different issues. Every child has different things that they're working on and struggling with. If we treated them all the same with the same rules and the same consequences, then we would be equal but we would not be fair. Being fair means that we treat everybody based on what they need. If we start treating kids or adults differently, then what we will hear is, "You're not being fair. You let her get away with something you don't let me get away with." My response is always, "Each of you is dealing with different things and we're really trying to be fair as much as we can. So you may think that she's getting away with things that I don't let you get away with, but you're able to do things that she has difficulty with." You don't get into diagnosis. You don't get into anything else. We really want to try to be fair, but we can't be fair if we treat everybody the same. Having served as a direct care provider over the years it is so much easier to treat everybody the same than to treat everybody truly individually.

Likely Co-Occurring Disorders with an FASD

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

- Schizophrenia

- Depression

- Bipolar Disorder

- Substance Use Disorders

- Sensory Integration Disorder

- Reactive Attachment Disorder

- Separation Anxiety Disorder

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

- Traumatic Brain Injury

- Medical disorders (e.g., born with a seizure disorder, heart abnormalities, cleft lip and palate)

The list above includes likely co-occurring disorders with an FASD. We often see people with co-occurring ADHD, schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder, or substance use disorder. All of these disorders have a genetic vulnerability, and one of the things that research has shown that causes genetic vulnerabilities to develop into full-blown disorders is the number of stressors somebody experiences in their life and their ability to cope with stressors. Those with an FASD have multiple stressors throughout their lives and poor coping mechanisms. If they have the genetic vulnerability to developing one of these disorders, they are more likely to develop the disorder. A study of 80 mothers who gave birth to children with an FASD found that 7% of these birth mothers had schizophrenia (Astley, Bailey, Talbot, & Clarren, 2000). That's seven times the national average, which means at least 7% of these children had the genetic vulnerability for schizophrenia and would more likely develop it. This is even more likely if we don't recognize the FASD early on and provide the children with the right supports. That's because schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder, and untreated ADHD often have high rates of co-occurring substance use to self-medicate. Even if these are co-occurring, the treatment for these disorders needs to be modified if they also have an FASD.

Another likely co-occurring disorder is sensory integration. Individuals with an FASD may have sensitivities to light, foods, temperature, texture, and the taste of certain foods. Loud sounds bother them, even though they make a lot of noise. If we recognize that a child has a sensory integration disorder early he or she should be referred for early intervention services, which often includes occupational therapy. Physical therapy can be helpful if they have fine and gross motor coordination problems, which many do. Speech and language therapy helps them if they are slow in developing speech and language. Early intervention is very, very effective, and the earlier it's started the better.

They may have a co-occurring reactive attachment disorder and/or separation anxiety disorder, especially if they've been moved around a lot. Also, if they've been moved around a lot they may have a lot of separation anxiety when it's time to go to school. That may be demonstrated by acting out behaviors. Co-occurring post-traumatic stress disorder can occur because of the repeated abuse and trauma. Traumatic brain injury may be co-occurring because, as I said, they may get hit by a car, suffer blunt head trauma on top of the FASD, get into a fight, fall, or hit their head. They are five to 60 times more likely to have certain medical disorders. So any child who was born with a seizure disorder, a cleft lip or palate, certain atrial or ventral heart abnormalities, someone should be asking about prenatal alcohol exposure. It is one of the causes of these. Not the only cause, but it's one of the major causes. Also included in this list is scoliosis or curvature of the spine. A number of medical disorders are more likely due to prenatal exposure.

Possible Misdiagnoses for Individuals with an FASD

- Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD)

- Conduct Disorder

- Intermittent Explosive Disorder

- Autism/High Functioning Autism

- Reactive Attachment Disorder

- Traumatic Brain Injury

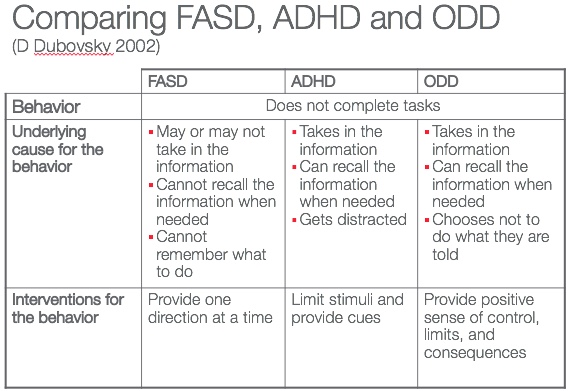

In addition to co-occurring disorders, we have certain misdiagnoses, some of which look the same as the co-occurring disorders. So does it matter? What difference does it make? If it looks like ADHD or it looks like oppositional defiant disorder we'll just treat that. Well, from my point of view it does matter, so I developed a series of charts. One of the things Bill taught me is that I couldn't just be verbal. I had to be visual as well.

Figure 2. Chart comparing FASD, ADHD, and ODD.

Figure 2 is an example showing three individuals demonstrating the same behavior. One has a true oppositional disorder, one has a true ADHD, and one has a true FASD. You've given them all three instructions. In a classroom, it may be go hang up your coat, sit down in your seat, and get out your reading book. At home, it might be go upstairs, get in your pajamas, brush your teeth, and get into bed. Whatever it is, you've given them instructions. It could be a parent who's given them instructions. Regardless, they don't follow through. The behavior is exactly the same for all three of these individuals. What we tend to do, in this idea of treating everybody the same, is we go from the behavior, the first row, to the last row which is what do we do about the behavior, and we don't stop and ask what's causing the behavior. One of the most important questions I think to ask for any behavior for any individual, not just those with an FASD, is what is causing this behavior? Because that tells us what to do. The behavior doesn't tell us what to do. What's causing the behavior tells us what to do. Let me share an example of why it's important to look at what's causing the behavior. In my last job I wrote and taught some courses on youth and violence. In researching those courses, I found that there were a number of people in jail for violent behavior where they found tumors in certain structures of their brain. When those tumors were removed, they had no more violent behavior. So no matter how much they were going to be consequenced for that behavior it would never get them to change the behavior. It was due to the tumor. So look at the individual with an oppositional disorder. This person took in the information that you told him, stored it in the brain properly, and could recall it when needed. He could repeat the three things you told him to do, and he said he just didn't feel like doing it. These are the individuals where that reward and consequence approach can be helpful. Always give them a positive sense of control: You can do this now or in five minutes, which would you prefer? That's giving the person some sense of control instead of do this now or else. Sit down with a person with a true ADHD. You might have to help him focus, but he can tell you the three things you told him to do, because he took the information to his brain, stored it properly, and could recall it when needed. His problem was that he got distracted. He started to do one thing, then got distracted. But if you could get him on target by limiting stimuli and providing him with cues, he can do the three things he was told to do because he knows those three things. The key is that if they can't do that environmentally they may need medication to help them filter out stimuli and focus. If you sit down with the individual with a true FASD and if you ask him the wrong question which is, "Why didn't you do what I told you?" the answer is going to be, "I didn't feel like it." Many individuals I've worked with over the years have told me it's better to be seen as bad than being seen as stupid. Those are the words that they used, and they're right. Because if you act out, nobody's going to ask whether you understand what was going on. We'll deal with the behavior. But, if you ask them the right question which is, "What did I tell you to do?" they probably won't tell you because they can't remember the three things that you told them to do. Even if the information gets into the brain it doesn't get stored properly and they can't recall it when they need it. So the intervention needs to be very different for these three individuals. It is very important to figure out what is causing this behavior. Keep these common misdiagnoses in mind as you're working with children with FASD and remember that the behaviors may look alike, but again, the treatment needs to be different.

Similarities Between FASD and Autism

- Both are developmental disabilities

- Both affect normal brain function, development, and social interaction

- In both, the individual often has difficulty developing peer relationships

- In both, there is often difficulty with the give and take of social interactions

- In both, there are impairments in the use and understanding of body language to regulate social interaction

- In both, there is difficulty expressing needs and wants, verbally and/or non-verbally

- A short attention span is often seen in individuals with Autism and an FASD

- In both, we may see an abnormal sensitivity to sensory stimuli, including an over- or under-sensitivity to pain

A lot of people ask questions such as, "Doesn't this look like autism?" I've had physicians tell me in the past, "I know that this is probably an FASD, but if I diagnose them with autism then they can get services." Often we can't get services if they have an FASD, especially in terms of mental health services or behavioral health services, because it hasn't been in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders until now. There is a term called neuro-developmental disorders that is associated with prenatal alcohol exposure. It's Neuro-Developmental Association and it has a code in the DSM-5 and has an International Classification of Diseases code. There are similarities between FASD and autism in terms of how they present, especially socially. But there are also striking differences, as seen in figure 2.

Differences Between FASD and Autism

FASD | Autism |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 3. DIfferences between FASD and Autism.

In true autism, the token economy approach can be effective while it is not terribly effective in FASD. Those of you working in early childhood education may often see these kids being diagnosed with autism. The other thing about autism is it usually presents at about two or three years old where the first couple years of life were more normal development. In FASD if we look back, even if we haven't picked it up early, the difficulties were there from birth on. The other thing is that when I see somebody diagnosed with autism who is very friendly, very outgoing, jumps in your lap the first time they meet you, or gives you a hug and a kiss, my antennae go up. I'd say that's probably not autism. That could well be an FASD, because of that difference in that lack of stranger anxiety. It's very different in these two types of individuals. Verbal communication may be slow to develop but is not commonly significantly impaired. Even in true autism we still see that hand flapping, the toe walking, and the difficulty in both receptive and expressive language. In FASD we don't tend to see hand flapping and toe walking, and we see much more difficulty in receptive language than in expressive. So as they get older they may be talking all the time. They may be constantly talking, which drives people crazy and annoys people. Taking in information is difficult. Often in true autism, there's either no verbal speech, or it's echolalia, repeating the ends of words or sentences of others, or robotic speech.

Brain Damage in FASD

- Prenatal alcohol exposure leading to an FASD causes brain damage

- Behaviors are often due to brain damage

- Behaviors often appear to be purposeful and willful when they are not

- Understanding the brain damage helps us understand the behaviors and develop appropriate interventions

- Typical approaches such as evidence-based practices will often not be effective due to brain functioning

We know that there are certain structures of the brain that are damaged by prenatal alcohol, and this is really key to understanding the structures that are damaged. What we think those structures do helps us understand why we need to modify what we do with these individuals.

Basal Ganglia and Caudate Nucleus

The basal ganglia is a group of structures in the back of the brain that controls motor activity. We see a number of children with an FASD who have fine and gross motor coordination problems, and children in adolescence who have balance problems as well, which puts them at risk of falling. That may be due to damage in the basal ganglia. It may be why they could benefit from physical therapy early on. There's another area in the basal ganglia called the caudate nucleus, and what research is finding is that even when the overall brain size is smaller than it should be, the caudate nucleus is even smaller than it should be for that brain size in those affected by prenatal alcohol. We think the caudate nucleus has responsibility for cognitive abilities and emotion and the expression of emotion.

Hippocampus

The hippocampus also has responsibilities for emotion and the expression of emotion. A lot of children with an FASD are seen as having no conscience and no remorse. This may be because another child gets hurt and they're laughing or they've done something wrong and you're talking with them about what they've done wrong and they're smiling or fooling around. We often think they have no conscience and no remorse. It may be a disconnect between what they are feeling and how that feeling is expressed facially and verbally due to damage in the caudate nucleus and the hippocampus. So we may need to teach them affect regulation, which is putting words and facial expressions to the entire range of feelings and model that for them. That means not going into work where you're angry about something and smiling and saying, "I'm really angry." That's not modeling good affect. The hippocampus is responsible for not only emotion and the expression of emotion, but also controlling aggression, memory, and learning and taking in new information. All of these are impaired in individuals with an FASD.

Corpus Callosum

The corpus callosum is a bundle of fibers that connects the right and left halves of the brain. Nobody's sure exactly what it does, but what we have found is that by providing children under the age of seven bimanual exercises to do, the thickness of the corpus callosum increases. Bimanual exercises are any exercises that use the two hands independently, such as juggling, swimming, playing the keyboard, and karate. What it's doing is forcing the two halves of the brain to talk with each other by building nerve connections across the two hemispheres of the brain. We can change brain structure by providing those activities. We don't know if it helps after the age of seven, because that research wasn't funded. We don't know if increasing the corpus callosum improves functioning because that research was not funded either, unfortunately. But we do know that we can help change brain structure and I think that we should provide everybody with bimanual exercises.

Frontal Lobes

The frontal lobes have very important responsibilities including abstract thinking. People with an FASD across the IQ span tend to be very literal in their thinking in deciding what to do in a given situation, in controlling aggression, and in processing humor. What we often see in kids and adults with an FASD is they'll laugh at a joke if other people are laughing, or they'll laugh when somebody's kidding around with them if the other person is laughing, but they can't understand that it's a joke. They typically think the person hates them or is out to get them. With Bill, I could always tell when he didn't get a joke. Someone was joking with him and would say, "Bill, just joking with you. Don't take it seriously." Years after Bill got his diagnosis of FAS his fourth-grade teacher said, "You know, thinking back, another kid in the class would tell a joke. Bill would laugh along with the rest of the class and then turn to me and say, 'I don't get it. 'What's so funny?'" That's a red flag that we totally missed at the time.

Amygdala

The amygdala is an egg-shaped body deep inside the limbic system that's responsible for controlling aggression, stress, and anxiety, and recognizing danger and fear. That's really important, because that lack of stranger anxiety as children, as adolescents, and adults puts individuals with an FASD at such high risk for abuse and trauma. It's important to recognize that this is probably damage in the amygdala of the brain. Don't have them experience a dangerous situation expecting that they will learn to do something differently. We have to really think about what situations they may get into and model those situations with how we would like them to respond. Role playing is a great way to do this. It should be done over and over again, because memory is impaired, probably due to damage in the hippocampus and damage in certain other areas of the brain.

There was a study that was done a few years ago that found that those with an FASD had severe impairments in an area of the brain called the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, as compared to a control group (Astley et al., 2009). That area of the brain is an area that's responsible for what we call immediate or working memory. That's what we rely on whenever we tell somebody to do something. If you say to a child, "Go hang up your coat. Go over and get a book to read and come back and sit in your seat," you're relying on their working memory to do that. If their working memory is impaired, they'll set out to hang up their coat and maybe get to do that, maybe not. If they do get to do that, they might have lost the program and may start talking to other kids, playing around, and be seen as a disruptive child. We won't recognize that that's damage in working memory. This is why we have to do one direction, one step, one rule at a time. Long-term memory is less impaired, but it means a lot of repetition to get it past damaged working memory into long-term memory. Again, it's understanding what's causing the behavior. It's not willful that they don't want to follow through. It's that they don't remember what they need to do. This is also whyyou need to do something different for families who aren't following through with what you've told them to do.

What to Expect from a Person with an FASD

- Friendly

- Talkative

- Strong desire to be liked

- Desire to be helpful

- Naive and gullible

- May “get it” one day and not the next

- Older than their age in some ways and childlike in others

- Difficulty identifying dangerous people or situations

- Difficulty following multiple directions/rules

- Model the behavior of those around them

- Literal thinking

These are the kids who are very friendly, often very talkative, really want to be liked, and really like being helpful. They're very naive and gullible. They believe anything anyone tells them. Anything they see on television must be real. One day they get it and they do everything they're supposed to. The next day they do nothing they're supposed to, so it looks like their behavior is willful, but that's really typical. In some ways, they behave older than they really are, and in some ways much younger than they are. As a 28-year-old, Bill could act like a 35-year-old and be articulate and intelligent, and he and I used to do presentations together. He could be articulate and intelligent, yet a half hour later he could be acting like a six-year-old. That's charming in some ways and frustrating in others, but that's so typical for people with an FASD. I talked about the dangerous people in dangerous situations as well as the difficulty following multiple rules, and remember these are brain-based issues. I talked about modeling the behavior of those around them, so if they are with negative peers they will model that behavior. Also remember that they are very, very literal in their thinking.

Language Issues in FASD

- Early language development often delayed

- Often very verbal as adults

- Verbal receptive language is more impaired than verbal expressive language

- Verbal receptive language is the basis of most of our interactions with people

Their expressive language is better than their receptive langaugage so they can talk a good game, repeat the rules, and repeat what they need to do, but they can't follow through. Unfortunately, everything we do is based on verbal receptive language processing. All of our parenting and most of our education is auditory learning. All of our treatment systems of care and our correction systems are based on verbal receptive language processing skills. Most of our evidence-based practices are based on verbal receptive language processing skills. That's a problem for those with an FASD. If you see somebody with an IQ of 125 and you're talking to them and they're nodding and maybe repeating something back you might think that they've gotten it. But not with this group. So we have to use different senses. The more senses we use such as visual and tactile, the better. Another sensory issue for some of these individuals is having difficulty with certain fabrics. They typically can't stand the feel of tags that are often sewn on the inside of clothes. They may destroy their clothes and look destructive, but it may just be that they can't stand the tags. Tagless clothing is really good or turning clothing inside out helps as well. Be aware of certain fabrics that they don't like the feel of. Those are all sensory issues due to the prenatal exposure.

Importance of Recognizing an FASD in a Caregiver

- If caregivers with an FASD are not recognized, they are often seen as uncaring, neglectful, or sabotaging approaches

- They may not show up on time for appointments

- They may not follow through on multiple and/or verbal instructions

- If a caregiver may have an FASD, the approach to them needs to be modified

So as I said earlier, it's also important to recognize this in a caregiver, because if we don't they may be seen as neglectful and uncaring when they don't show up to their appointments or they don't follow through with their instructions. If we suspect that about a caregiver who is saying, "Oh, I'm sorry. I forgot about the appointment" or "I'm sorry, I got so busy that I didn't get to take him to the doctor," or whatever it was, take a step back and think, "Hmm, could this be somebody with a possible FASD themselves? What could we modify to help them be successful with their child?"

Issues in Addressing Behaviors

- Many people think that if we find the right motivating factor, the person will do what we want them to

- We use what the person likes to do and does well as the motivating factor

- If he or she does not respond, we say that we haven’t found the right motivating factor

- Although this approach may work for some people, it is not effective with many with an FASD as well as others

- If someone has difficulty in abstract thinking, they often do not know why they do not get the rewards

- There are really only two explanations if one does not get cause and effect

- People are mean for no reason

- They are “bad”

- With repeated similar experiences, thinking they are “bad” may become their self image

- People work hard at doing things to support their self image

- Much of this is not conscious

- We need to change our approach

- We need to incorporate a true strengths based approach to everyone

- Identifying strengths and abilities needs to be foremost

- We need to move towards a positive focused system

So again, I talked about the motivating factor piece already and that it doesn't work often. I also talked about the fact that if they don't understand why they're not getting their rewards it must be that they're just bad or people are mean for no reason. They may have developed this concept that they're just bad, and then they reinforce that. We really need to develop a strengths-based approach and move to what I call a positive focused system. It's recognizing what are the strengths in this individual, in the family, in providers, and in the community. This is very important, and we don't do that enough.

Strengths

- The first step in helping someone to succeed is to identify strengths and abilities

- Everyone has strengths

- Sometimes, they get the person into difficulty

- There are times when the individual and those around cannot identify any strengths

- Our systems do not encourage the identification of strengths