Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Kids with Kids: How to Support Them, presented by Sherrie Segovia, PsyD.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- describe the developmental needs and risks of teen parents.

- identify at least three screening tools for use with teen parents.

- describe three key intervention strategies.

Introduction

I recognize that you may or may not have experience working with teen parents. However, I hope to provide an additional learning opportunity in whatever role you hold in your organization. I had the privilege of working with a multidisciplinary team that included teachers, case managers, social workers, health professionals, and mental health therapists. We jointly impacted the lives of many parents and their children. In my retirement, I finally reflect on my years of service to pregnant and parenting clients, particularly teens, and I want to share my experiences with you. During this course, I will share some specific cases of teen parents. Still, I will protect their identity by omitting their ethnicity, their gender, and any other information that might identify them.

During this course, I will offer an overview, briefly discuss infant mental health, review the pertinent theories of adolescence, identify related risk factors and possible protective factors, offer interviewing and assessment tools, discuss potential strategies and interventions, highlight the importance of self-care, and end with lessons learned. I have worked with pregnant and parenting teens for the past 40 years in various settings, including as a mental health therapist at a community counseling clinic and a program trainer at a foster care agency. In addition, I spent 25 glorious years at an Early Headstart program as a clinical manager and mental health coordinator.

In the first two settings, teens were not willing participants and were often mandated because of referrals from Child Protective Services. In the Early Headstart program, teen parents enrolled primarily because they needed childcare to go to school or work. In all these settings, I had to respond to numerous challenges. Working with teen parents is a difficult yet highly rewarding opportunity to impact both a teen parent and their children, kids with kids.

Touchpoint #1

Please take a moment to engage in the following exercise. Based on your experience or imagination, answer the following questions. We may share some of the same responses.

- List three concerns or challenges of working with teen parents.

- Identify three benefits or advantages of working with teen parents.

I was often challenged by issues of trust and lack of communication. I was also troubled by what seemed like unhealthy choices or self-destructive behaviors. At this point, I want to let you know that working with teens was not my preference. It was a teen that I saw during my master's internship that deterred me from pursuing private practice. Instead, I chose to work in social service settings. She was a spoiled brat seeking therapy because her daddy wouldn't buy her a Beemer (BMW). That's a true story.

Over the years, I was still reticent to work with teens, but they walked in the door, and we served them. Each time, I discovered that they had wonderful qualities as parents, eager to learn once the barriers were removed because they really cared about the well-being and future of their child. Since they were still young, they were more interested in preventing adversity and trauma than older parents. Once I approached them from their point of view, I found the road to progress much easier. I learned many valuable lessons along the way. There were tremendous opportunities when I exercised patience and understanding, given their young age and limited experiences. Because they tended to be more concrete, they were more receptive to suggestions or guidance, especially concerning parenting strategies.

I also think that it's important to understand that teen parents are extremely diverse in their backgrounds and situations, so working from their stories is where we need to always begin. Ultimately, the goal is to have a healthy child with a healthier teen parent using the advantages or strengths as your guide.

Infant Mental Health

In 2001, I had the privilege to participate in the formulation of a working definition of infant mental health at a federal conference in Washington, D.C. Basically, infant mental health encompasses a multidisciplinary approach to supporting parents with young children, meaning that everyone who interacts with parents is contributing to the mental and emotional well-being of children under three. I also co-authored an article published in ZERO TO THREE, titled "Infant Mental Health at Hope Street is Everybody's Business." For this reason, this course is intended to provide useful information and strategies to early childhood teachers, case managers, and other staff working with families with young children. Using this definition means that anyone who works with parents and young children is, in fact, an infant mental health professional. According to the ZERO TO THREE Infant Mental Health Task Force, "Infant mental health is the developing capacity of the child from birth to three to experience, regulate or manage, and express emotions, to form close and secure interpersonal relationships, and explore and master the environment and learn all in the context of family, community, and cultural expectations for young children."

Theories of Adolescence

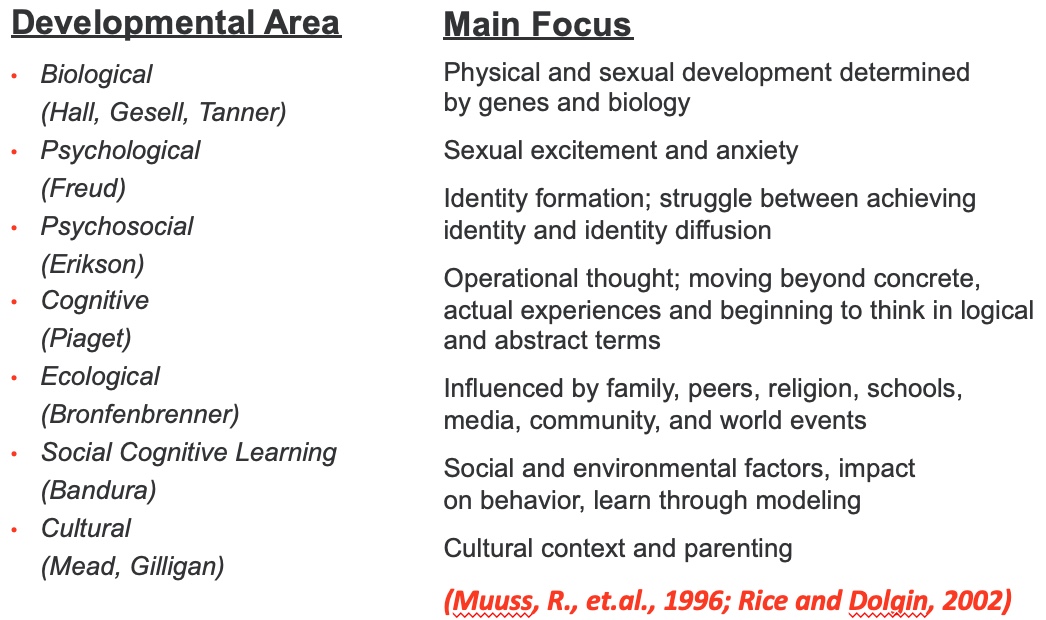

To better understand, it's important to review their developmental stage and their typical behaviors, feelings, and thoughts. You may have heard that teens are big toddlers with more pronounced behaviors, and I agree. When parenting my own two children, I found the teen years to be the most difficult developmental stage. Hopefully, reviewing these theories will provide a better understanding of teens and a framework to support you with strategies. In Figure 1, you can see each theory's developmental areas and main focus.

Figure 1. Theories of adolescence.

The biological theory is focused on physical and sexual development, which is determined by genes and biology. The psychological theory is focused on sexual excitement and anxiety. For psychosocial, the focus is on identity formation and the struggle between achieving identity and identity diffusion. For cognitive, the focus is on operational thought, moving beyond concrete, actual experiences, and beginning to think logically and abstractly. Ecological focuses on the influence of family, peers, religion, schools, media, community, and world events. Social cognitive learning focuses on social and environmental factors and their impact on behavior and learning through modeling. Cultural focuses on cultural context and parenting. Hopefully, that provides a framework of understanding for you.

Risk Factors

Pregnant and Parenting Teens

Unfortunately, many risk factors and negative outcomes are associated with teen parents.

- Strong link between intimate partner violence (IPV) and teen mothers

- Strong link between child abuse and teen mothers

- Strong risk for repeat pregnancies within teen years

- Strong risk for depression and suicidal behaviors

- Strong propensity for children with multiple partners

Research has shown that 70% of intimate partner violence victims experienced their first IPV incident before age 25, and a quarter of them before they turned 18. I found that addressing IPV with teens was more challenging since their parents and partners were not necessarily living in the same household, so identifying and providing support was always difficult. Child welfare global sources indicate higher rates of child abuse for both the parent and the child.

Center for Disease Control (CDC) statistics indicate 25% of teen moms have their second child within 24 months of their first baby, and in some states, they have two or three during their teen years. Related to this point, less than 2% of teen moms earn a college degree by age 30, which is unfortunate because studies have shown a strong correlation between maternal education and their children's academic outcomes.

Suicide is the second leading cause of death for youth ages 10 to 24, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Association (SAMHSA). Since partnerships are brief between teens their age, particularly young fathers tend to have children with multiple and sometimes simultaneous mothers. We served children from the same father and different mothers at my agency a few times, which got complicated. I once had the incredible experience of working with a teen father who was only 14 years of age, and I can't tell you how much that impacted my team and me. Surprisingly, he was very attentive to his child and open to feedback.

Risks for Children of Teens

There are inherent risks associated with teen pregnancies that are often multiple and multi-generational, including prior adverse childhood experiences, otherwise known as ACEs, which involve any type of trauma or abuse experienced under age 18. Generally speaking, the younger the teen parent, the more increased risks there are. I once worked with a 10-year-old who became pregnant after being molested by a family member. Unfortunately, both were placed in foster care in separate homes. Teen parents tend to engage in problematic behaviors, including poor nutrition, substance use, unhealthy relationships with their parents and peers, and negative attitudes toward authority.

- Low birth weight

- Developmental delay/disability

- Higher risk for child abuse/neglect/foster care

- Dropping out of school

- Health problems

- Incarceration

- Teen pregnancy

- Underemployment/unemployment

Because of their physical and social immaturity, preterm labor is more common in teens, resulting in low birth weight and developmental delays or disabilities. Typically, pregnancies aren't planned. I often worked with multi-generations of teen pregnancies, and I was astonished by the young age of the grandmothers, who were sometimes in their early 30s and with a child about the same age or younger as their grandchild. We frequently served grandmothers and mothers in our program who had young children.

Protective Factors

I hope I haven't depressed or deterred you from serving teen parents. The good news is that some conditions and skills contribute to overall well-being and mediate the potential risk factors. These protective factors highlighted in childwelfare.gov are opportunities for positive change that builds on teens' inherent strengths and resilience. Anyone working with teen parents has the opportunity to promote these skills.

- Cognitive ability

- Sense of optimism

- Self-efficacy or agency

- Academic skills

- Problem-solving skills

- Relational skills

- Reversible, long-acting contraception

- Involvement in positive activities

One major area of focus is increasing parental competencies and offering the presence of a caring adult. Often, a teacher or case manager can be a positive role model. I used to emphasize to my team that we parent the parent with unconditional care that they never had. In other words, we considered ourselves protective factors. The major approach that we used is often referred to as psychoeducation, which is a form of teaching. By providing information and increasing knowledge, the person learns new skills and coping methods leading to empowerment. Much of what drives teens is misinformation or poor examples of relationships. I once worked with a teen gang member who was very apathetic about her future and unwilling to set goals for herself. She said, "Why bother? I might be dead tomorrow." I offered her another perspective, which was that of her child. Only then would she understand that she needed to set goals.

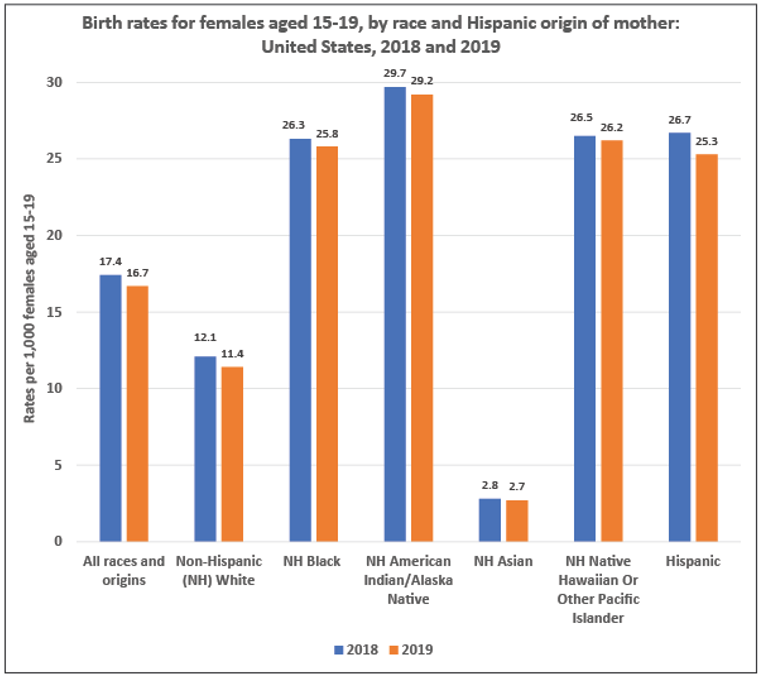

Figure 2. Birth rates from 2018-2019.

This chart demonstrates the most recent trends in reducing teen pregnancies across all groups. However, these are still high rates of teen births, particularly for a developed country. Sexual activity in teens is comparable in the United States to other countries. However, the use of birth control is much lower. We must continue our efforts and focus on preventing initial and subsequent pregnancies.

I once worked with two sisters, ages 14 and 16, and both had babies. The 14-year-old was the first to become pregnant, and then her sister decided to join her. I think she thought it was cool. I had another case of an immigrant who was 14 years old with an infant, and she informed me that she was considered an older parent in her native village. I told her that she was considered very young in the United States and needed to understand how people would react to her.

Impact of Technology

Most agree that technology has resulted in huge benefits for society. However, the negative effects have been noted, especially in teens. Teens are increasingly suffering from self-esteem issues and suicidal ideation due to negative interactions on social networking sites. I have seen children as young as nine with suicidal behaviors, and I think the social isolation from COVID has also heightened these concerns.

- Cell phones

- Texting

- Sexting

- Computers

- Access to global issues

- Immediate and uncensored information

- Social networking

- Privacy

- Relationships

- Bullying

- Sexual predators

Another highly concerning matter is the distinct possibility of sex trafficking. Unfortunately, I encountered two teen mothers that were victims of sex trafficking. On the other hand, teens do respond more readily to texts, which is a great way to communicate with them whenever possible. I also used internet resources to educate them on nutrition, parenting, and mental health.

Cell phones, texting, and sexting are problematic. I saw several situations with very concerning sexting. Another problem with technology is computers with access to global issues and immediate and uncensored information, much of which is wrong information. Social networking brings issues of privacy, relationships, bullying, and sexual predators.

Interviewing and Assessment Tools

Ethnographic Interviewing

It's extremely important to work from the person's point of view, particularly with teen parents. I always remind them that I can't help or support them if I don't know, so I must ask them questions.

Ethnographic interviewing provides a means of asking questions in a way that is more effective in discovering the person's perspective and can strengthen the working relationship with the professional. I firmly believe that assessments are also interventions and that providing opportunities for a safe space to share is beneficial. In this approach, there are three types of questions.

- Descriptive - Questions that ask to describe experiences; for example, what is your child's typical routine or schedule?

- Structural - Questions following up on responses to descriptive questions such as, what are some challenges or barriers to adhering to your child's daily routine?

- Social dimensions - Questions intended to discover the social context include questions like who supports or inhibits you in your family?

There are general principles or guidelines to follow when asking questions that will enhance the relationship. Remember that teens are generally distrustful of adults and unwilling to share information.

- Ask for use instead of meaning

- Use open-ended rather than dichotomous questions

- Restate what the person says by repeating the exact words

- Summarize the person’s statements and offer an opportunity for correction

- Avoid multiple questions

- Avoid leading questions

- Avoid using why questions

For instance, saying, "Give me an example," versus "What do you mean?" will elicit more specific or useful information. Open-ended questions beginning with wh-, such as who, what, when, and where, are always best. Otherwise, you will get a simple yes or no. An example of a wh- question is, who is your best friend? Restating and summarizing responses indicate that you are fully listening and not misunderstanding the person. This is where active listening is so important. Active listening means listening to hear and not to respond.

Multiple, leading, and why questions are often unproductive, confusing, and can be interpreted as judgmental. I find that why questions can be particularly problematic. It reminds me of when I used to ask my own children, "Why did you do that knowing that it was wrong?" That never resulted in any positive outcomes. I believe that practice makes perfect, especially when learning a new skill. While this may come naturally to you, there is always room for improvement and professional growth. I try to adhere to the adage that brevity is the soul of wit and to leave space for listening, even though teens tend not to talk much to adults. Many years ago, I had counseling sessions with a teen who chose to remain completely silent for the entire hour. It was brutal for me, but essential to demonstrate my commitment to their autonomy and control.

Touchpoint #2

Take a moment to practice asking questions using the principles above with a real or imagined teen parent. I always found that coming from a place of genuine curiosity for the client's sake was the best place to start. One of my challenges was listening intently and trying to set my own agenda aside. However, I think we need to be honest with teen parents and transparent with our professional goals.

As you practice asking questions using ethnographic interviewing principles, note if you find any challenges. Remember to be genuine, using your care and concern for the client as your guide.

Assessment for Sexual Activity

Asking about sexual activity can be extremely difficult for you and for the teen. In this case, take every contact whenever possible to get this information. Every so often, there are windows of opportunity. Over the years, I found that teens sometimes trusted their children's teachers more than their case manager or mental health therapist. They often disclosed tidbits during daily interactions at drop-off or pick-up.

For this reason, I regularly provided training on managing disclosures, particularly when staff was sworn to secrecy. One of the secrets teachers often told was that the teen was pregnant again or that they dropped out of school. The latter was a huge problem because they would no longer be eligible for childcare.

The CDC offers the five Ps.

- PARTNERS

- Sexual PRACTICES

- PROTECTION from sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

- PAST history of STIs

- Prevention of PREGNANCY

The first P, partners, refers to how many partners they had in the past or have currently. The next P is sexual practices. You want to understand what type of sexual activity they're engaged in. The third P is protection from sexually transmitted infections (STIs) if they're using any. The fourth P is any history of STIs. The final P is the prevention of pregnancy. On the last point, I was always surprised that teen moms were not concerned about getting pregnant again. They often told me that they wanted more children sooner than later. It was a huge challenge for me to hide my reaction or disappointment.

Assessment for Violence

As mentioned, getting specific information on these sensitive topics can be challenging, but it is extremely important for preventing injuries to the teen parent and/or the child. All clients need to be reminded that you are a mandated reporter and that there may be a possibility of a child abuse report, including exposure to domestic violence. There were a few occasions when I worked with teens who were gang members and shared that they had physical arguments with other teens in front of their child. I always emphasized that making a report provides an opportunity for change, and I offered them my commitment to supporting them through the process. I used to remind my team that our obligation was not just reporting but supporting and preventing subsequent child abuse.

Many years ago, a teen mother approached a teacher after she experienced an extremely traumatic incident with the father of her child, and she asked her for support. She had a visible wound on her arm, and she shared with the teacher and me that she was held hostage by the father of her child for hours. He threatened to kill her and then himself. Somehow she managed to convince him to let her go and leave their child with him so that he had assurance that she would return. Fortunately, we were able to work with law enforcement to secure the child and detain him without any further violence. After it was over, I can tell you it was traumatic for the client and our team.

This assessment for violence is provided by Connected Kids Safe Strong Secure. The acronym is FISTS.

- Fighting

- Injuries

- Sex

- Threats

- Self-defense

F is for fighting. This is where you can get a sense if the teen is engaging in any kind of physical violence or even verbal violence. Next, you want to know if they've ever been or are currently injured. Using your observations is important here. S is for sex. You want to get a sense of not just if they're engaging in sex but if they're being forced to have sex, otherwise known as rape. Even in a consensual situation, meaning in a relationship, it's still considered violence. T is for threats. You want to understand if they're being threatened in any way. The final S is for self-defense. I always asked about a safety plan if they were in an unsafe situation, and if they didn't have one, I would suggest finding a resource to provide them with a safety plan.

Assessment for Alcohol/Drugs

Asking about substance use is challenging because most people will deny their behaviors. I understand what it's like to hear these questions every time I have a physical exam and I'm asked about drug or alcohol consumption. Let me just say that I don't use drugs, but I have an occasional glass of wine. Since substance use and abuse can be common in this age group, it's extremely important to identify and provide support, particularly with pregnant and parenting teens. This assessment is provided by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Do your friends drink or use any drugs?

- Yes—What about you?

- Yes—How much and how often?

- No—Praise the choice of not drinking or using drugs and ask about behavior with friends

- No—What about you?

- Yes—How much and how often?

- No—Praise the choice of not drinking or using drugs and having friends who support similar behaviors

The assessment begins by asking, "Do your friends drink or use any drugs?" You may get one of two answers, yes or no. If they say yes, follow up with, "What about you?" If they say yes again, follow up with, "How much and how often?" If they say no, praise the choice of not drinking or using drugs and ask about behavior with friends. If they were to say no to the original question, then ask them again, "What about you?" If they say yes, ask again, "How much and how often?" If they say no, praise the choice of not drinking or using drugs and having friends who support similar behaviors.

Assessment for Perinatal or Postpartum Mood and Anxiety Disorder (PMADs) (PHQ-4)-Scale

There are differences between teenage depression and adult depression, as teens tend to be more irritable or angry, have physical issues, have more sensitivity to perceived criticism, and often withdraw or isolate themselves. The PHQ-4 includes four questions. There are other types of patient health questionnaires, such as the PHQ-2, which is two questions, and the PHQ-9, which is nine. These are readily available, and you can easily access them on an internet search.

These assessments are also available in other languages and are commonly used in various health settings. You may have seen them yourselves. They're used to screen for depression and/or anxiety and make referrals or provide additional services. They include a scale to rate the level of severity, but for your use, I suggest you use questions with your own modification and comfort. Some professionals ask the client to fill out the questionnaire or use it during a structured interview. I am a firm believer in using your own observations to formulate your own questions, such as I noticed you seem sad, have you been sad lately? For how long? In these cases, simply asking about their feelings is seen as a form of caring and concern.

Here is the PHQ-4, which I got from PrimeMD.

Over the last two weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems?

- Little interest or pleasure in doing things?

- Feeling down, depressed or hopeless?

- Feeling anxious, nervous, or on edge?

- Not able to stop or control worrying?

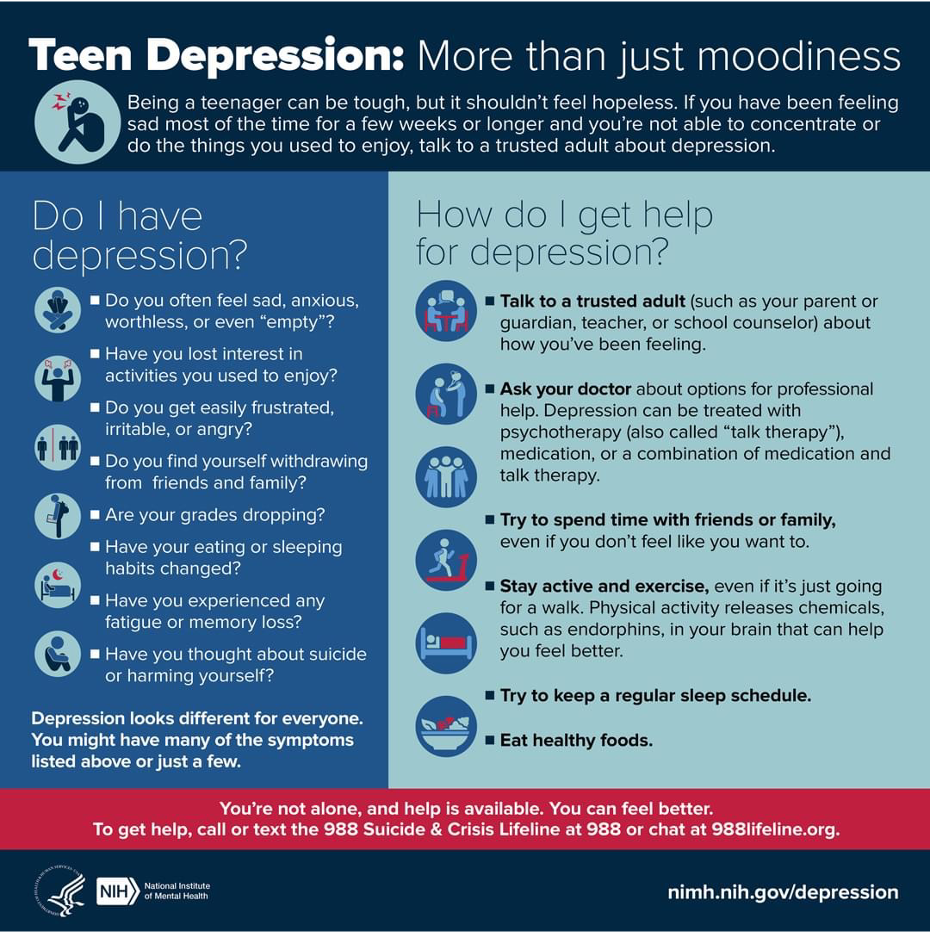

A distinct marker for suicidality is feeling hopeless and helpless. Figure 3 is a great resource to offer teens in general. I always offered this information to all teens in our program, and this resource can be found on the National Institute of Mental Health website. I also included it in the references at the end.

Figure 3. Resource from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Assessment for Suicidality

Many years ago, I learned that suicide prevention is everybody's business, and I routinely provided training to the entire team at my agency. It's important to be prepared to ask tough questions and to be well-informed about how to respond and what to do when receiving a critical response. Simply asking someone if they plan to kill themselves does not increase the likelihood that they will do so. Instead, it is considered an intervention because it indicates someone cares for them. Again, these questions can be found on the SAMHSA website, samhsa.gov.

Many years ago, I worked with two mothers who experienced suicidal and homicidal thoughts. In other words, they both had thoughts about killing not only themselves but also their child. Fortunately, I could provide effective support in both situations in partnership with my team members and other agencies. Be prepared to call for emergency support if someone answers yes to all the questions listed below.

- Are you feeling hopeless about the present or future?

- If yes, ask…..

- Have you had thoughts about taking your life?

- If yes, ask….

- When did you have these thoughts, and do you have a plan to take your life? Do you have the means?

- Have you ever had a suicide attempt?

- If yes, ask….

- Have you had thoughts about taking your life?

- If yes, ask…..

It raises concern extremely high when they've answered yes to all of these questions. If not, and if there are still some concerns, offer them a suicide or crisis hotline such as 988, which is a national network of hotlines. I also suggest you know the number for the local psychiatric emergency team, sometimes called PET, PURT, or PMRT. My strategy for seeking emergency support for clients is to let them know that I will take all measures to protect them because I care for them and their child.

It's not uncommon for people to have feelings of hopelessness and helplessness about the present or future, but I think the other parts are more concerning, especially if they have a specific plan and they have the means to take their lives. I cannot reiterate that everyone needs to be prepared to confront or address someone who is suicidal.

Touchpoint #3

I recognize that not everyone is comfortable with using these assessments or screening tools. However, prevention is the best intervention. Whenever children are involved, the stakes are quite high. Take a moment to review the previous assessment tools. Even as a trained mental health professional, I had difficulty asking tough questions. Still, I overcame these challenges when confronted with an extremely vulnerable or distressed client. Remember that preparation is key; you can't go wrong by asking with care and concern.

Again, feel free to shorten it to only one question. For instance, when assessing for IPV or domestic violence, I would simply ask are you afraid of anyone? Then you can go into a wh- question such as who or when? As I said, consider the preceding assessments using your comfort with these tools. Remember that you can modify them and make them shorter, brief, and more sincere. Finally, be prepared to take action when using these tools, particularly when they are disclosures that indicate any danger to the parent and/or the child.

Strategies and Interventions

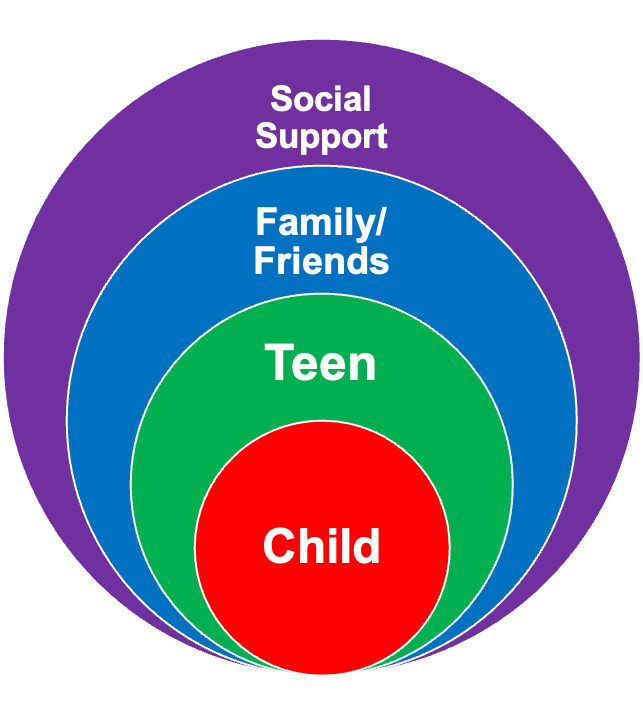

I mentioned Bronfenbrenner's ecological system approach earlier when I spoke about adolescent development. Working with families and young children needs to involve a holistic approach with access to additional services. Working with other partner agencies is important if your organization is exclusively childcare. More than likely, teen parents are living with their parents or an adult caregiver. There can be both benefits and challenges in these situations. My approach has always been to work directly with teen parents whenever possible and include their adult caregivers with their permission.

While in most states, the age of consent for mental health services and confidentiality is 18, in some states, including California, it's 12. That being said, it is important to clearly identify the teen parent as the parent. Sometimes grandparents can influence a teen parent in concerning ways, such as encouraging the teen to use physical discipline. I say discipline or suggest that the child remains on the bottle to prevent them from crying. Again, that's beyond three years of age. Or in other cases, the grandparent may undermine the role of the teen parent with mixed messages to the staff.

I witnessed some children calling their grandmother Mom and their mother by their first name. Whenever there was a conflict between addressing the grandparent or the teen parent, I always focused on the child's best interests. It is, unfortunately, not uncommon to be placed in between and forced to take sides. I want to emphasize that grandparents can be extremely helpful and need help and support. Primarily, I serve teen mothers, but I always ask permission to include the child's father. The best approach was to work with both parents and serve the teen fathers' needs. I encountered single teen fathers occasionally because the mother was not involved due to child abuse issues.

Figure 4. Bronfenbrenner's ecological system approach.

To review the ecological systems approach, you'll see that it does involve comprehensive services focusing on a variety of areas of need. It also involves serving at least two, in this case with teen parents, and sometimes three generations, so be prepared to support all generations. As I mentioned, including fathers is extremely important. Be child and teen-driven when you're looking at goals. Finally, it's important to be flexible over time as things change.

Interventions

I learned much from the staff and clients that I supported over the years. Essentially, they taught me better techniques each time I failed in my attempts to serve them. I once heard that clients don't care how much you know. They only need to know how much you care. I always ask for permission when offering guidance, suggestions, or directions. For example, is it okay if I make a suggestion? Of course, the challenge then becomes that they might say no. Self-disclosure can be a powerful tool, such as sharing that you were a teen parent.

Offering unconditional positive regard, coined by Carl Rogers, is also a highly effective approach. This means you tend to separate the person from their behavior to avoid judgment and continue caring about them. This allowed me to serve clients who were previously abusive or had committed illegal acts. The term use of self describes how helping professionals can integrate aspects of themselves into the relationship while still maintaining healthy boundaries. I believe that this is a powerful tool, particularly for teens. An example of this approach is to use your own feelings to move the client, such as I am really worried about you staying with your abusive partner. When all else fails, I share the bottom line and let them know the consequences of their behavior, particularly if it can endanger themselves or their child.

- Trust and rapport building and exploration of the perception of teens’ own history (how they see their story)

- Collaboration, contact, and communication with various agencies

- Patience while mediating own agenda

- Reflective practice while reviewing relationships with others, including home visitors/case managers

- Use of self including honesty, concern, respect, appropriate self-disclosure

- Consistency

- Being direct with compassion

- Openness without judgment or disapproval

It's important to have a warm handoff when working with other agencies and have particular contacts you can refer clients to with their permission. It's important to be direct with compassion because clients can sense when you're not being direct or genuine. Being open without judgment or disapproval can often be difficult.

Here are some other strategies or best practices.

- Establish collaborations and partnerships with other programs serving teens.

- Provide direct resources and appropriate referrals.

- Use effective screening tools and interviewing skills.

- Increase parenting skills and child development knowledge through interactions and modeling with useful information.

- Improve parent-child interactions, and strengthen parent-child attachment.

- Offer high-quality childcare with teen engagement opportunities.

- Promote financial literacy.

I want to reiterate that it's important to have that warm handoff. I remember when teachers forged strong relationships with parents and taught them many life skills, including how to take the baby's temperature or diaper it properly. Our staff often observed how teen parents appreciated their child's newfound skills, and often the children progress more than their parents. We use that as a vehicle for their own change.

As I said earlier, establishing collaborations and partnerships with other programs that serve teens is very important, as having knowledge of what you have available locally. Sometimes we make referrals that don't fit the client's needs. It's extremely important to involve teens in every aspect of childcare. Promoting financial literacy is the final point, but I would also discuss money and time management. Teaching them these skills can be very beneficial.

Self-Care

Hopefully, you already understand that you cannot help others if you are not well. Helping professionals are also human and have their own past and current issues. Working with traumatized clients can be traumatizing. I used to present workshops at conferences on caring for the caregiver or nurturing the nurturer. Above all, it's important to prioritize yourself and be compassionate to yourself because working with clients can be very difficult and can trigger you, bring up memories, or challenge you.

Establishing healthy boundaries is a big part of self-care because we bond strongly with our clients, especially teens. Sometimes, we feel as though we're their parent. I think just observing that boundary is a professional relationship. Practice patience, not just with the client but also with yourself. Know that you are doing your best and are not perfect. Seek support by having access to someone who can provide professional guidance, professional support, and a safe space to share some of the challenges you are experiencing in serving clients. Remember, in this field, it is not uncommon to have burnout. You want to avoid that.

Lessons Learned

Strategies and interventions cannot work without an established professional and parent relationship. It's important to remain flexible and understand that teen parents can be highly resistant and will implement change in their own time. Many clients returned years later and told me I was right, but it took them a long time to understand that. I'm hoping that you understand that relationships are key in moving clients. This is the most powerful tool that you have. It's also important to understand that one approach does not meet all needs or clients.

Crises are difficult, and embracing them is important because they present opportunities and the possibility of change. Celebrate adolescence because while I personally find adolescents challenging, I think many aspects of adolescence are very positive. Teach once and learn twice. I've learned much more from my staff and clients than I think I taught them myself. The final point I've already talked about is the importance of self-care.

In closing, I fondly remember a particular 17-year-old mom with a child our program identified as having autism. At the time, she was living with her 19-year-old husband, who was abusive, and they promptly had two additional children. Last year and 25 years later, I reconnected with her, as most of our clients routinely reached out to other staff and me, including their children's teachers. She shared that she divorced her husband and eventually became homeless with her three children. However, she and her children were resilient; as I mentioned, crisis equal opportunity equals change, and they were able to overcome their circumstances. When I saw her last year, she had purchased her own food cart, and she proudly reported that her children were all responsible and successful adults, including her child with autism, who is running a productive car sales dealership.

Final Touchpoint

We all give our best to our clients, hoping they have a better future. After participating in this learning experience, I want you to highlight your own takeaways. In working with clients and particularly teens, it is paramount that you are prepared and comfortable with your approach. Given this instruction, identify one assessment tool and strategy you plan to use. There's a wealth of information on SAMHSA and childwelfare.gov. Feel free to reach out if you have any additional questions regarding this topic. I am passing the baton to you and wish you the best in working with teen parents.

References

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. (2017). Facts for families: Children having children. Vol.31. www.aacap.org

Cardone, I., Gilkerson, L., & Wechsler, N. (2008). Teenagers and their babies: A perinatal home visitor’s guide. Washington, DC: ZERO TO THREE.

Kroenke, K, Spitzer R.L., Williams, J.B., & Löwe B. (2009). An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics, 50(6), 613-621.

Martin, J.A., Hamilton, B.E., Osterman, M., & Driscoll, AK. Births: Final data for 2019. National vital statistics reports: from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System, 70(2), 1–51.

Mollborn S. (2011). "Children" having children. Contexts, 10(1):32-37. doi: 10.1177/1536504211399048. PMID: 22102797; PMCID: PMC3219505.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health. (Updated 2021). NIMH Strategic Plan for Research (NIH Publication No. 20-MH-8120). Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/sites/default/files/documents/about/strategic-planning-reports/NIMH-Strategic-Plan-for-Research-2021-Update.pdf

Westby, C., Burda, A., & Mehta, Z. (2003). Asking the right questions in the right ways: Strategies for ethnographic interviewing. The ASHA Leader, 8, 4-17 doi:10.1044/leader.FTR3.08082003.4

Citation

Segovia, S. (2023). Kids with kids: How to support them. Continued.com - Early Childhood Education, Article 23836. Available at www.continued.com/early-childhood-education