Editor's note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Supporting Young Children's Social-Emotional Literacy - Part 1, presented by Pamelazita Buschbacher, EdD, CCC-SLP.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Define “school readiness” and its relationship to young children’s social and emotional development.

- Define ‘emotional attachment’ and its relationship to young children’s behavior.

- Define ‘emotional literacy’ and its relationship to young children’s behavior.

We know that a large and complex feeling vocabulary is very important not only for young children but for all of us. It's a prerequisite skill to being able to regulate your emotions and to successfully interact with other children, with your peers, with your siblings, and with adults. The reverse happens as well as it is truly a transactional relationship. This is the first of two presentations which I will provide information on the value in recognizing and acknowledging and supporting young children's development of a rich emotional literacy.

NAEYC and Young Children

The code of ethics from the National Association for the Education of Young Children says that we have responsibilities to children as seen below.

Responsibilities to children:

- I-1.5—To create and maintain safe and healthy settings that foster children’s social, emotional, intellectual, and physical development and that respect their dignity and their contributions.

- P-1.1—Above all, we shall not harm children. We shall not participate in practices that are disrespectful, degrading, dangerous, exploitative, intimidating, emotionally damaging, or physically harmful to children. This principle has precedence over all others in this Code.

We know those are a given. Sadly, over the years I have experienced situations in which children weren't respected as learners and children weren't in safe environments. Now we know more and we strive more and I am betting that by virtue of the fact that you're completing this course, you value children's emotional development.

“School Readiness” What is it?

We hear a lot about school readiness, in relationship to kindergarten but we also hear about readiness in terms of preschool or even as speech and language therapists. At one time, my caseload was composed entirely of young children who presented challenging behaviors in their other therapy situations. Therefore, the parents were told they weren't ready for speech and language therapy or they weren't ready for preschool or they weren't ready for kindergarten. Oftentimes, we have a model when we talk about readiness that is a one-size-fits-all. Skills are taught in fragments and they're isolated. This is the way we teach reading, this is the way we teach emotional development, this is the way we teach children to sit in circle time. This information comes from a great deal of research by Pretti-Frontczak and others.

A New Definition for Readiness

What they and I propose is a new definition of readiness. Pretti-Frontczak et al. (2016) said, "Readiness is a developmental process, largely unpredictable and highly influenced by the child’s social relationships and interactions. Readiness requires a whole-child perspective where individual differences are expected, valued and celebrated."

Readiness is a developmental process, so it's developmentally unique to the child, largely unpredictable and highly influenced by the child's social relationships and interactions with others. Their social relationships and interactions with their peers, with their siblings, and with other adults in their various environments. Readiness requires a whole child perspective, where individual differences are expected and they're valued and they're actually celebrated.

Elkind (2014) said:

Readiness is not in the child’s head. Readiness is a relationship, not a trait. Readiness always refers to the relation between the child and the demands and/or the expectations that are being imposed upon him or her.

Readiness is not what's in a child's head but again, it's a relationship, it's not a trait. We know that it refers to how children in a given environment interact with one another but also, how adults interact with them. It assumes competence on behalf of the children and sees them as active learners in the process and engaging in what would be considered a transactional relationship.

Readiness Remedies

Here are some remedies for readiness. If we can conceptualize readiness as a relationship, we know it's going to be complex because we know as adults that our relationships are complex and they will change as a child interacts with adults and in a variety of situations, whether that’s out on the playground, in circle time, one-on-one, or in a group situation. We know that teaching and learning also is a social transaction between young children and adults. These are things that the research tells us, but we also know intuitively.

If we're really talking about readiness, then we want to understand the whole child. When children come to preschool or they're in speech and language therapy, they have had many hours and possibly even many years with a variety of adults, both in their home environments and out in the community. Based on those experiences, they will develop at a natural pace. In some situations, children have further complications in that they might have developmental delays or they may have an identified disability, such as autism or Down syndrome or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

When adults and others assess and then we nurture and then we teach those skills that children need, within context, then we have a better outcome not only for the children but also for us as educators. Oftentimes, I've heard in early childhood programs as well as therapy situations, occupational therapy or speech and language therapy, children being told to use your words. It's a little bit complicated if you have a child who is nonverbal or a child who comes from a home where you really don't express how you feel about things. For example, if someone takes your toy, you grab that toy right back or you slug the child. That child might be your friend, but will probably not be your friend after that. Oftentimes, we need to look at the whole child and understand where the child is coming from and what skills they may be lacking that we need to teach.

It is important to expect and value those individual differences in children, both their social, being based on their home and community environments and their cultural. Many years ago, when I first started working as a public school speech and language pathologist there were two brothers who were new students at the school. Both boys' native language was Vietnamese. They had recently arrived from Vietnam and had been referred to me for speech and language therapy. This was strange because we didn't have an English as a Second Language program in the school and so, usually children with different languages were referred to the speech and language pathologist. This seems ridiculous because I didn't speak Vietnamese. Nevertheless, I approached a five-year-old who was the size of a three-year-old and I extended my hand and asked him to come with me and said we were going to do some fun things together. He looked terrified. I should have done my homework so that I would’ve learned that in Vietnam strange adults don't take children's hands and they don't look directly at children in the eyes. I did not understand his culture and I violated it right from the get-go. Since children acclimate very quickly and we were able to be more sensitized to what their cultural needs were, things worked out well and both boys turned out okay.

We also have to understand a child's developmental level. You may have a child who has delays due to a disability or who may have an unidentified disability or maybe lack of experiences in the home environment or out in the community. We need to be sensitive to that. When a five-year-old shows up at school we're sensitive to the fact that there may be some social differences, some cultural differences, and some developmental differences.

Elkind (2014) said, “To demand that all children be at the same developmental or achievement level because they are the same age is simply a denial of our biological and environmental variability.”

To demand that all children follow the same development, in the same order and achieve at the same level, just because they're the same age, denies not only the biological variability in children but also the environmental variability that we see in children.

Further on in the article, Pretti-Frontczak and others propose a more transactional shift which is integrated and personalized in nature. This includes looking at positive relationships and encouraging those positive relationships, where we engage with young children in authentic activities and integrate them throughout the day, providing appropriate learning experiences for children. We ensure that the environment itself is ready for the child, the home is ready for the child, and the community is ready for the child, to nurture the child in a way that he or she can reach her potentials both, emotionally and academically and socially.

Albert Einstein said, “Everybody is a genius. But if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid.”

I love this quote from Albert Einstein. I continually tell children, as I'm sure many of you do as well, "That was so smart, you're so smart."

I once taught a young boy who wasn't ready to read. He entered kindergarten and was supposed to learn how to read and they said, he's not ready to learn how to read. He was showing some emergent literacy skills, they just weren't where the school expected them to be, so they held him back for a year. Later when his IQ was tested, he proved to be on the genius level. Even as an adult, he believed that he wasn't very smart because he said to me, "Who is kept back in kindergarten?" That's very sad.

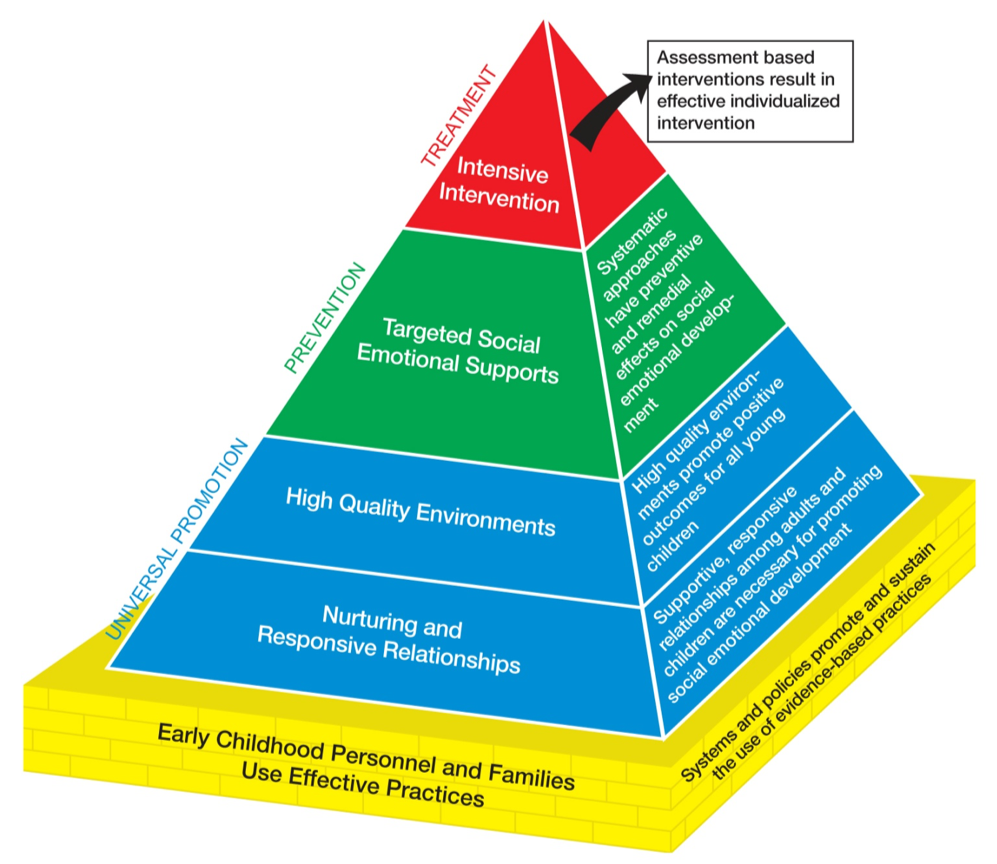

The Pyramid Model: Promoting Social Emotional Competence in Infants and Young Children

Figure 1. The Pyramid Model.

Created by and available from the National Center for Pyramid Model Innovations (NCPMI) at ChallengingBehavior.org

Everything I'm going to be saying for this presentation will be referring back to something called The Pyramid Model. Many of you may have heard of The Pyramid Model which is about promoting social-emotional competence, not only in young children but also in infants and young children. We’re talking from the get-go, from the time a baby is held by his mommy, all the way through age seven and eight.

You have a handout of The Pyramid Model that you can print out for reference and easier reading. At the base of The Pyramid Model is what I was talking about earlier, that early childhood personnel and families use effective practices that we know work well for children. This also includes having systems and policies in place that allow and support adults in using those effective practices for children. Today, I'm going to be talking about the blue level and a little bit of the green level. I won't be talking too much about the top of the pyramid.

When we look at the blue level, there should be universal promotion in all early childhood programs, whether that’s birth to three where we're in the home working with families or in situations where we're in childcare or preschool classrooms. The relationships should be nurtured, we should be responsive to young children, and the environments should be high-quality. I've had the opportunity to work in Head Start programs and support professionals there in implementing The Pyramid Model. They had very limited resources in terms of the types of toys they had, but we were able to find ways to design an environment that was very supportive for child learning.

When we talk about nurturing and responsive relationships, those are not only adult-child relationships but also adult-adult. Children are always watching and listening and they see how we interact with one another. That provides a model for them on how to interact with one another but it's also the teacher that greets each child when he and she come in the morning. The teacher might even ask, "How are you today?" The teacher listens and then responds and says, "You know what, I'm kind of tired today, I didn't get much sleep last night," sharing her emotions as well.

When we talk about the second part of the blue tier, high-quality environments support and promote positive outcomes for all children. We have to have the yellow base and those two blue tiers if we're going to be able to support children who present with consistent challenging behaviors. First, we have to provide this for all children. But of course, children as I said, come to school and they come from many environments and have experienced many different types of relationships. Sometimes, we have to teach those social skills to children and provide those emotional supports for children with a lot of visuals. I'll be talking today about some of the visuals that we and teachers have found to be very effective in their classrooms, to teach children the social and emotional skills they need to be successful later on. Then, at the very top of the pyramid, are those intensive programs we provide for children who do present us with challenging behaviors that are very persistent.

The Pyramid Model was developed by identifying evidence-based practices that promote the social and emotional outcomes of all children. That's the key to it all because it is felt that that is the basis to all learning if we're going to help children reach their potential. These practices promote the skill development of children with social, emotional, and behavioral delays to prevent the need for more intensive supports later on and provide an intervention that's effective for children with persistent challenging behaviors.

Go to challengingbehavior.org and you will find an immense amount of resources, including 24 user-friendly “What Works Briefs.” These are short, brief articles that speak in a way that we can share with parents so that they understand the approach that we're talking about the importance of supporting children's social-emotional development. Some are available in both English and Spanish.

Sample topics include:

- #3 Helping Children Understand Routines & Classroom Schedules

- #4 Helping Children Make Transitions Between Activities

- #8 Promoting Positive Peer Social Interactions

- #21 Fostering Emotional Literacy in Young Children

- #24 Attachment: What Works?

One of the briefs is helping children make transitions between activities. So many of us have had those situations where things start to fall apart in the classroom during transitions. There are many children that have trouble with transitions. Brief number eight speaks to promoting positive peer social interactions. Brief number 21 talks about fostering emotional literacy in young children. I'm going to talk in a little bit about what I mean by emotional literacy. Number four talks about attachment. Attachment is so critical and sometimes we don't pay enough attention to the emotional attachment support that we need to provide for children.

Emotional Attachment

Emotional attachment is defined as the continuing and lasting relationship that young children form with one or more adults, especially in terms of the child feeling secure and safe when in the company of a particular adult. When a baby is in the crib and the baby cries and mommy shows up and says, "Are you okay?" that reinforces the attachment. Some of our children don't have those kinds of experiences and we need to then provide that in the classroom or in the therapy situation.

What We Know About Babies’ and Toddlers’ Brains

The baby’s or toddler’s communication of emotions and needs establishes the learning pathways in the brain that leads to all other physical, cognitive and emotional learning!

Babies and toddlers communicate their emotions and then we interpret their emotions and we label their emotions. They establish very early on in the brain things such as:

- I can count on you to be there for me

- A smile means something

- A frown means something

- An angry voice means something

- You will be there

- I'll be safe

- I'll be secure

- You'll be there for me emotionally.

It covers all the physical, cognitive and emotional learning that is so critical for very young children.

Young Children Who Experience Secure Attachments

- Trust their needs will be met by adults

- Trust that adults will be emotionally available to them

- Learn to communicate in a variety of ways

- Begin to manage their strong emotions with help from adults

- Are more affectionate with peers

- Can focus on learning

- Demonstrate more empathy for others

We know that when young children experience secure attachments, they will trust. Trust is important. In fact, when I first start teaching a child or teaching in a classroom, I truly emphasize the importance of trust, that children will be able to trust us and trust that adults will be emotionally available for them. A friend of mine grew up with a mom who had bipolar disorder and her mom could not always be there emotionally for her. There were times her mom would be in a manic phase and be so depressed that she just withdrew to the bedroom. My friend as a five-year old would then have to take care of her three-year-old brother because mom wasn't available to them. You can imagine what it’s like when a five-year-old and a three-year-old come to kindergarten or come to preschool and the primary adult in their life hasn't always been emotionally available to them.

Children learn to communicate in a variety of ways, including verbally and with their eyes. We know that as adults, 85% of what we communicate is nonverbal; the nods, the smiles, the hand movements. That's a high percentage of communication that is nonverbal rather than verbal.

Young children who have secure attachments learn to manage their emotions with help from adults. They're more affectionate with their peers and they show empathy. It's amazing to see a 12-month old cry and another 12-month old look over with a very worried face. They learn that level of empathy if they're in a secure environment and have secure attachments. Then they can focus on other learning, such as motor learning, fine motor learning, learning to read, learning to write, and art. Then as I said, they learn to demonstrate empathy for others.

Young Children Who Do Not Experience Secure Attachments

- Learn not to trust adults will be there for them

- Stay close to an adult to get their needs met

- Learn to not seek out an adult when distressed to help them with their emotions

- Hide their strong feelings and/or withdraw

- Seem disorganized and confused about how to behave in relationships with peers and adults

Young children who don't experience secure attachments learn not to trust adults or they find an adult and stick to that adult-like glue. Have you ever had a child who follows you around the classroom as if the child were a shadow? I would wonder about the child's level of emotional attachment. Then some children also learn not to seek out an adult when they're distressed because when they needed help in the past the adult didn't provide it. They might learn to hide strong feelings because they’ve been told that only babies cry or big boys don't do this. The child might have fallen down, gotten hurt, and cried and was told, “Shake it off.” To say that to a three-year-old seems a little bit cruel. They seem disorganized and may seem confused about how to behave in relationships.

There's a poem that I would like to share with you from 1976 by Dorothy Law Nolte titled “Children Learn What They Live.” You can find it on the internet. I think every classroom should have it framed and displayed in a way that all adults can see it. It starts, “If a child lives with criticism, he learns to condemn. If a child lives with hostility, he learns to fight. If a child lives with fear, he learns to be apprehensive. If a child lives with pity, he learns to feel sorry for himself.” Then it goes on a little bit more about the negatives, but here are the positives. “If a child lives with encouragement, he learns to be confident. If a child lives with tolerance, he learns to be patient. If a child lives with praise, he learns to be appreciative. If a child lives with acceptance, he learns to love.” It goes on to state more about those positive relationships and how important the environment is for a child, and at the very end, it says, “If you live with serenity, your child will live with peace of mind. With what is your child living?” is how the poem ends. I think you'd find it really helpful to read the entire poem. It really is exceptional.

Arrival/Greeting Transition

One example of how to strengthen attachment is to use an arrival/greeting transition. For each child, giving a warm welcome and a smile. Place yourself at the child's level. Get down low, not looking down at the child, but actually getting on your knees or sitting in a chair and greeting every single child that comes into a classroom. Have a short conversation with the child, "How are you today?" Label the child's emotional state. For example, if he comes in crying and he's hanging on mommy, label the emotion. If he comes in and he just runs in and he's so happy to be there that day, label his emotion. Label your emotions as you start the day. If a child is upset, acknowledge that and then reassure the child.

Do or say something related to your theme or day’s activities. Tell the child what's going to happen that day. We know that prediction and structure are really important for young children. If the child's having a difficult time transitioning into a morning activity, maybe use a song to help with the transition. I've seen teachers use those so well and I'll give some more examples during part 2 about some visuals that can help in those situations. Although I'm talking about talking, some children can't tell you how their day was or can't label their emotion in a verbal way. I'll be showing you a few examples of some of the visuals that you can find on challengingbehavior.org, but also some that I've made for children that you'll be welcome to copy and make on your own as well.

We Can Make a Difference

There is a wonderful handout called “Positive Solutions for Families” you can download from challengingbehavior.org. To access it from that site, click on Implementation, then click on Family Engagement. Scroll down to Related Resources, then click on General Resources. (Note: At the time this course was created, these directions were correct. The location of this handout may have changed over time.) “Positive Solutions for Families” provides eight solutions that are described to help families and to support them in feeling competent and confident as they support their child's emotional attachment and emotional literacy.

Positive Solutions for Families

- Keep your expectations realistic.

- Plan ahead.

- Clearly state your expectations in advance.

- Offer limited, reasonable choices.

- Use “First… Then….” statements.

- Catch your child being good.

- Stay calm.

- Use neutral time.

It's important to keep our expectations for young children realistic. I remember hearing a mommy say to an 18-month old, "You should know better," when he almost ran into the street. He's 18 months old. How is he supposed to know better? Keeping expectations realistic and how we interact with and how we talk to children is critical.

Plan ahead for an excursion or the classroom or circle time.

Clearly state your expectations to children and doing so with visuals oftentimes. This may include the rules of the classroom, how to line up, circle time, or playing outside.

Offer choices. There's so much research that shows that providing choices for children is almost like magic. Maybe a child doesn’t want to come to snack or maybe a child needs a diaper change and he doesn't want to have his diaper changed right now. I heard a teacher of this little four-year-old say, "Do you want to get your diaper changed now or in five minutes?" He looked at her and said, "Now." All he wanted was a choice.

Use, first, then statements. For example, first, eat snack then we're going to go outside and play, or first hang up your coat then you can go play in the block center.

Catch children being good. Sometimes we don't do enough of that.

Stay calm and using neutral time. Neutral time is that time in which we can teach children the skills that they might need apart from the emotionally laden. If children are not sharing so well and there's a tug-of-war, then maybe take a little time during circle or some one-on-one instruction, when everything's neutral and emotions are not flaring, to work on how we share and how we take turns.

We Can Make a Difference

- Foster a secure relationship with the child

- Interact with other adults in child’s environment in healthy ways

- Be warm, responsive and affectionate with all children

- Engage in meaningful conversational interactions with children

- Be physically and emotionally available

- Comfort children when they are distressed

- Follow child’s lead

- Set safe behavior boundaries

- Be consistent

- Be a resource for parents needing mental health support

We can make a difference. We know that. That's why we're in early childhood. We're not babysitting, we're teaching. We can foster secure relationships with children as we are teaching them. We can do this as we interact in healthy ways and by are warm and responsive and affectionate with all children. Engage in meaningful conversations with children as if they are learners and they are meaning makers. Be physically and emotionally available for children. Comfort children when they're distressed rather than dismissing them like the child that fell down and daddy said, "He'll be okay, just get up."

Follow a child's lead. We hear that so often in early childhood. If a child is really interested in playing with the dinosaurs, follow his lead and allow him to determine the play, but at the same time, have an environment in which there are safe boundaries for children. Be consistent with all children. Sometimes, there are children that we warm up to very easily and there are some children that we don't warm up to as well. There are some children that warm up to us very easily and some that could care less and they like the assistant teacher or they like the speech pathologist better, and they interact with that person differently.

What is really critical because we are a team, is being a resource for parents, because parents know their child best. The environment might not be as supportive as it needs to be for a child socially and emotionally, but parents know their child and it’s important to use them as a resource as well. We also need to provide them the supports they need, in terms of mental health, financial resources, or things that might make the home safer or more consistent in terms of food. It is critical for us to be able to do that since the child is a product of their family and supporting the family is critical for all of us.

Emotional Literacy

Emotional literacy is the ability to read (identify), label, understand and act upon the feelings (emotions) of oneself and others in a healthy and socially acceptable manner.

I use the term emotional literacy and the Pyramid Model uses the term emotional literacy and many of my colleagues do, because we refer to it as the ability to be able to read (identify), and then label, understand and act upon our own feelings. We should be supporting a child to be able to read, label, understand and act upon his or her feelings or emotions about himself, but also to be able to read others' emotions in a healthy and a socially acceptable manner.

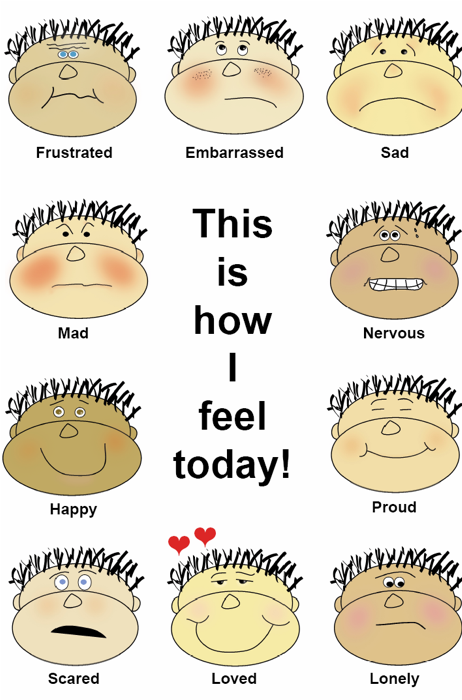

Look at all the faces in figure two and identify what emotion you see in each one.

Figure 2. Faces.

We see a red, hot face that looks like anger. We see a child yawning, but that's not emotional, that has to do with wellness, I'm tired. A crying child with a very red face could be angry, sad, or be frustrated because a game's not working the way she wants it to. The girl in the jean jacket looks pretty upset. Then we look at the balloons and we see what appear to be very happy children around the balloons. The little girl with the blonde, curly hair might be scared. The little girl with the bandage on her elbow was probably crying before and now she seems pretty happy that the adult that she trusted could help her take care of the boo-boo on her elbow. Then look at the little guy hugging his mommy. How many of us have friends or our own children who have hugged us tightly when a stranger approached or a new person came to the house?

Variables Impacting a Young Child’s Emotional Literacy Development

- Child’s temperament

- Developmental status of the child

- Parental socialization skills

- Parental mental health

- Environmental support

- Disability

- Educator/therapist support of child emotional literacy

There are several variables that impact young children's emotional literacy development.

The child's temperament. We all come into the world with our own temperament and then we interact with the world. Some people are quieter. Some children are more pensive and they watch a situation before they go into it. Then we have some children that jump into those situations and create a lot of chaos and their temperament is more, “Let's take charge of the world, hello world, here I am today.”

The developmental status of the child, including where he or she is motorically and visually. Are there some sensory processing issues that are impacting on the child's emotional literacy? I had a little boy that I taught and he didn't play outside on the playground at his childcare center very well. He pretty much stood off and watched the other children play and it was assumed that he didn't want to play. Then, when I watched closely outside on the playground and then, in the classroom, I saw that he avoided things like puzzles. I asked his teacher if his vision had been screened. The teacher spoke to the parents about that and he came to school the next week and he had thick glasses on, which meant that his vision was pretty bad. All of a sudden, like a light switch went off, he was drawn to the puzzles and he would chat with his friends that were sitting next to him doing puzzles. He was outside climbing all the equipment and riding the bicycle and playing with his friends and laughing. It's important to look at the whole child.

We have to look at parental socialization skills. What type of environment does the child come from? Are his parents quieter? For example, I have been in several situations working with children on the autism spectrum where when I met the parents it was very apparent that one of the parents also fell on the spectrum of autism. In the home environment, there were challenges in terms of social and emotional development by virtue of the challenges the parent faced.

The parents' mental health impacts children as well, as evidenced by the story I told earlier about my friend who was raised by a mom with bipolar disorder. The environmental supports for a child, not only out in the home but in the community and in the classroom impact children’s emotional literacy development too, as well as disability.

Also important to children and an impact on their emotional literacy development is your emotional literacy, as the educator. Are you limited in angry, happy, sad and frustrated and maybe don't have the nuances of apprehension, bravery, being nervous, being tired and being able to tell other folks that? We have to understand our emotional literacy.

Emotional Literacy Schematic

- Reading of affective cues

- Self

- Others

- Interpreting of affective cues

- Cause

- Intent

- Clarifying of interpersonal goals

- Generating of solutions

- Making a decision

- Acting on decision

There is a schemata for emotional literacy in young children that was developed by Joseph, Strain, and Ostrosky in 2005. It's a more circular type of schemata, in which we talk about the child reading affective cues, being able to understand his or her emotions, but also the emotions of those around him, and then interpreting what those emotions are (affective cues). When we talk about affective with an a, we're talking about emotions. The child not only has to read the emotion, but the child has to think, you're using a loud voice, so you must be angry. Then the child has to think about how to interact with you, come up with solutions, make a decision and act on that decision.

Let’s look again at computer time and having to share a computer. For example, a child wants his turn on the computer and everyone knows that he pushes other children off the seat in order to get his turn on the computer and he doesn't read the effect that it has on his peer. We would work on having a visual for taking turns on the computer and how people feel and how he can take turns. In that case, the goal would be to share time on the computer, come up with solutions, and make a decision, and then act on it.

With this particular child, we designed a visual for that particular period of the day when four children would be able to get on the computer. We had a picture schedule of who was going to be first, second, third and fourth. There would be a 10-minute timer for each of the children so they know they would get a turn and that their turn was coming up. When your turn was over, you took your picture off. This solved a problem that was causing a great deal of pushing and shoving and arguing with the children. There is a kit that I'll be talking about in part two called the solution kit which helps children work through problems that come up through the day, with an adult's help.

Evidenced-Based Practices Supporting Young Children’s Emotional Literacy

- Healthy expression of emotions by adults

- Labeling and concrete descriptions of “all” emotions felt by adults and children

- Acknowledging and encouraging pro-social behaviors

- Visual supports

- Planned activities to teach and reinforce emotional literacy

There's a great deal of research now on good, solid, evidence-based practices to support children's emotional literacy that wasn’t available 10 years ago.

What we do know is important is that children need to be in environments in which adults themselves have a healthy expression of their emotions. It’s important that the children aren't seeing and hearing sarcasm among the adults or arguing among the adults. This supports children's literacy.

Labeling and concretely describing emotions works well to support young children’s emotional literacy. I'll show you examples of a couple of boards that are emotion boards that we've created that work very well in classrooms. If you go to Pinterest you're also going to see how a lot of people are very creative in ways to help children express their emotions or label their emotions.

It's important to catch kids being good. Catch them using pro-social behaviors. When someone is sharing, comment on it. For example, "You gave that toy to ______" or "You took a turn with the swing.” Another example is to say, "That was really nice to do that for your friend” or "You're reading a book with your friend. That's really cool that you guys are sharing a book."

There’s so much research to show that using visual supports helps young children. There’s a quote I really like that illustrates this. “I hear, I forget. I see, I remember. I do, I understand.” We should keep that in mind with small children. The visual supports help them remember.

Planned activities help them understand and reinforce emotional literacy for young children.

Why Acknowledge Positive Behaviors?

Research Supports Use of This Strategy

- Adults often attend to children for misbehavior & take for granted pro-social behavior

- Negative attention is better than no attention

- Negative adult reaction will only temporarily reduce challenging behavior (emotional expression)

- Most behavior is strengthened/weakened by what immediately follows a behavior

- More desirable behavior often has to be taught and reinforced

Why should we acknowledge positive behaviors? So often, the ones that stand out are those challenging behaviors. If you really want to have someone listen to you give a presentation, then all you have to do is title it about challenging behaviors because we know, they challenge us. Children sometimes provide many challenges for us throughout the day. Research supports catching children and acknowledging positive behaviors.

Too often, we attend to children for misbehavior and we take for granted that they're going to demonstrate pro-social behaviors. We also know that if we pay attention to those misbehaviors, those will probably reoccur, because negative attention is better than no attention. Let's give attention to those pro-social behaviors. The negative reaction of adults will only temporarily reduce the challenging behavior because the child got what they wanted. Most behavior is either strengthened or it's weakened by what immediately follows that behavior. If a child is acting in a pro-social way, such as taking turns, sitting and participating at circle, or out on the playground using the equipment in a very safe manner, and if adults are acknowledging it, more children will do that positive behavior more often. But sometimes, those behaviors have to be taught and we know they have to be reinforced.

Adults Can Acknowledge Positive (Pro-Social) Expression of Emotions

- Responding positively to desired emotional expression

- Ignoring most negative behavior

- Redirecting child to acceptable behavior

- Recording the number of times positive behavior occurs

- Designing and implementing a written positive behavior support (PBS) plan to be implemented by all adults in all the child’s environments

Adults can acknowledge those positive behaviors by responding positively and describing how you feel about it or describing the child's emotion. "Boy, you went down that slide so fast, you were really brave." Try to ignore most negative behavior unless someone's getting hurt. Redirect children to more acceptable behavior and keep track of those positive behaviors, seeing if a child is being more pro-social and is growing in that way. For some of our children, providing positive acknowledgments for pro-social behavior doesn't always work. These children need us to design a positive behavior support plan that all adults will implement to teach the child the skills that he or she needs to be able to interact in a very effective way with his peers and adults in his environment, whether that’s his preschool classroom, home, or out in the community.

What Can Adults Do?

- Label your own feelings

- Label children’s feelings

- Provide environmental supports

- Teach social-emotional skills through

- Games

- Songs

- Books (Bibliotherapy)

- Apps and computer games

What can we do as adults? We can label our own feelings about a situation, label a child's feelings, and provide environmental supports in terms of visuals and materials. There are wonderful commercial books about emotions and about pro-social behaviors. We can use songs and games. There are many apps that children like to interact with that support social-emotional literacy.

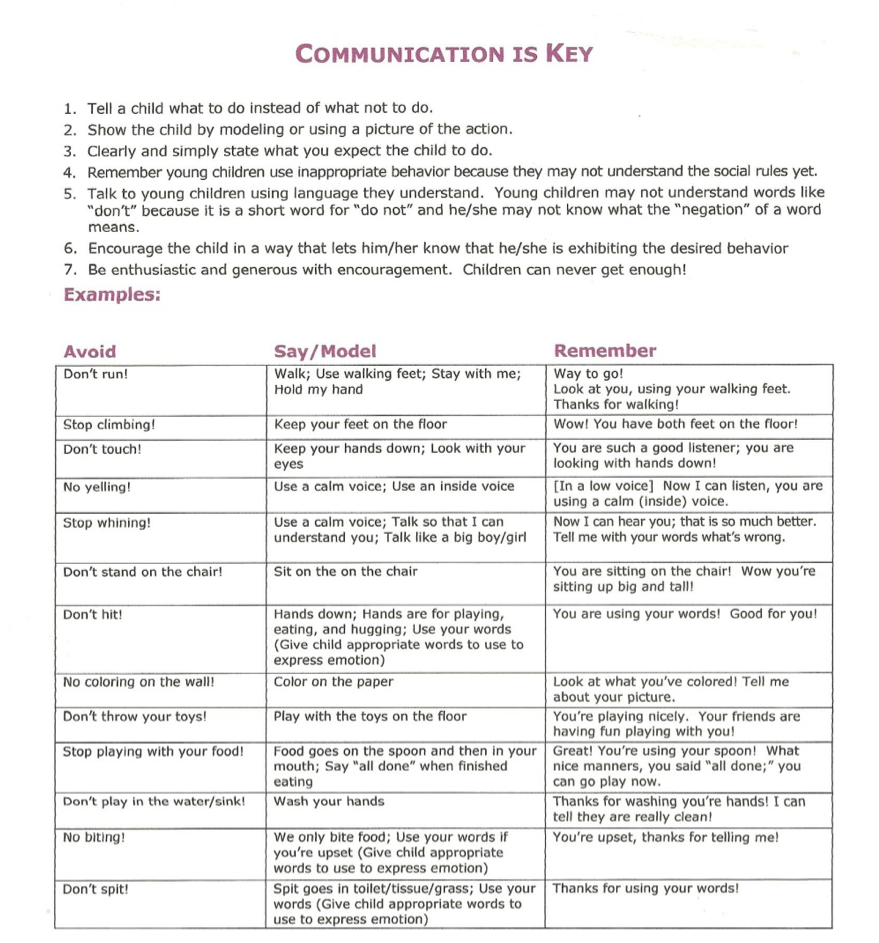

Communication is Key

Figure 3. Handout – Communication is Key

Take a look at your handout titled “Communication is Key,” also shown in figure 3. It talks about how communication is key for encouraging and supporting pro-social behaviors in children. Instead of saying, “Don't run,” we should say things like, “Walk; use your walking feet; stay with me; hold my hand.” Tell children what to do, instead of what not to do, because the last thing they hear is what to do. Then reinforce it, "Way to go! Look at you, you're using your walking feet."

Here's another example. "Don't stand on the chair." I heard a teacher say that. Wouldn't it be better to say, "We sit on chairs" or rearrange the environment so the chair isn't in a place that children can stand on it? In this classroom, the environment was such that standing on chairs was really cool. Instead of saying, “Don't stand on the chair,” we would say, “Sit on the chair” or “Bottoms go on the chair.” Catch a child when he's sitting on the chair. For example, if you have a child who tends to climb the furniture but all of a sudden you see him sitting in a chair say, "Hey you're sitting in the chair, great job."

No coloring on the wall. I remember that with my 18-month old. Instead, bring out the paper and say, "We color on paper," rather than, "No coloring on the wall." You can say, "No coloring on the wall," but make sure you end with, "We color on paper." Then, bring out the paper and give the child lots of opportunities to do that and make sure that it's available for the child because if the crayons are around and there's no paper around, you might have an 18-month old coloring on the wall again. I think you will find this handout very helpful.

Environmental Supports

- Emotion Boards

- Emotion Sign-in/Sign-out Charts

- Feeling Face Collage

- Solution Kit (www.challengingbehavior.org )

- Classroom Rules (4-5)

- Stated prosocially

We need to have environmental supports available for children. Many of the things I’m going to share with you are available at challengingbehavior.org. You can find examples of these things and download them, print them out on cardstock, laminate them, and use them immediately in your classrooms or in your homes.

Environmental supports include emotion boards and emotion sign-ins for when a child comes in the classroom. I've seen some really cool emotion boards where when children come at the beginning of the day they locate their emotion on an emotion board and put a picture of themselves on it. They put their picture on the picture of how they feel that day, whether it’s sad, tired, grumpy, or happy. This helps you know how your day is starting based on the fact that the child is telling you how he/she feels.

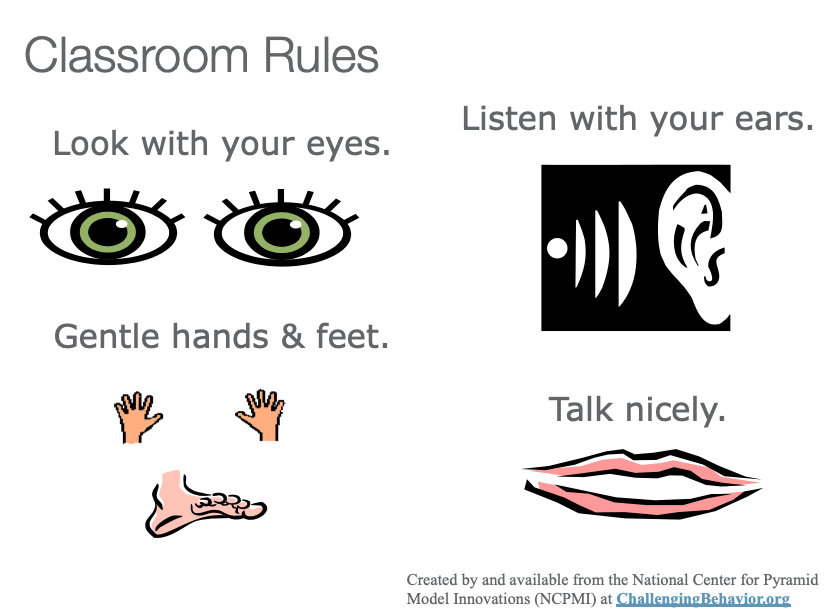

Other examples of environmental supports include feeling face collages and classroom rules. So often I've gone into preschool classrooms where I see 10 rules. The most you want for little children are four or five rules that are stated in a very pro-social way. Not, “Don't run in the classroom,” but rather, “Use walking feet.”

Solution Kit

Figure 4. Solution Kit.

Another thing that’s available at challengingbehavior.org is a solution kit, as seen in figure 4. You can print these out on cardstock and have them available for children to use. First, you would teach the children what they are and how to use them. The cards include ways that they can solve situations that happen in the classroom such as get a teacher, ask nicely, ignore somebody who's teasing you, say please, play together, share, and trade. They're very attractive cards to use and are available in two different sizes that you can print out.

Classroom Rules

- Only have a few simple rules (4-5)

- Involve children in developing the rules

- Address:

- Noise level; movement inside; and interactions with property, peers, and adults

- Post visually and at the child’s eye level

- Teach rules systematically

- Place classroom/therapy rules on a cue card ring for portability

- Reinforce rules at high rates initially and also throughout the year

Figure 5. Example of classroom rules.

As I mentioned before, there should only be a few simple classroom rules. Figure 5 shows an example of some classroom rules. Include rules such as look with your eyes, gentle hands and feet, listen with your ears, and talk nicely. I've used many versions of these rules in the classroom. Of course, you can't just display it, you first have to teach what those classroom rules are and practice those classroom rules with one another. They can address a variety of things such as noise level or movement within the classrooms and interaction. They should be posted at a level that children can see. Sometimes I've walked in the classroom and everything's posted at an adult level. Get down on your knees and find out where children will see what those rules are and teach them in a very systematic way and reinforce them throughout the day.

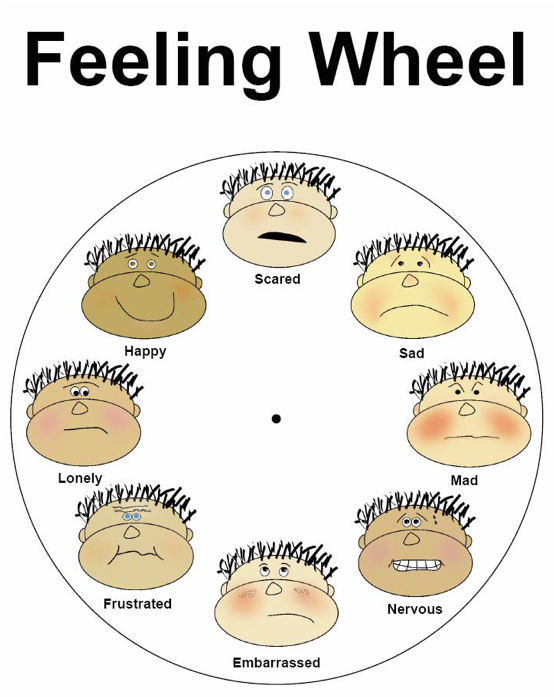

Feeling Charts

Figure 6. Feeling Wheel.

Figure 7. Feeling Faces.

Figures 6 and 7 show two examples of feeling charts that you can find on challengingbehavior.org. I have used the feeling wheel and I actually added on to the feelings there. I was teaching a second-grade boy who was challenged with stuttering and these emotions were not enough. We had to add other emotions such as brave. This boy had to be pretty brave to volunteer in the classroom to speak because he was afraid he would stutter. You can find a variety of emotion boards. I've seen some really clever ones made by teachers, therapists, and even parents. Parents love these. They put them on refrigerators and have brothers and sisters commenting on how they feel that day. If you're not so keen on these particular graphics, you can find a lot on the Internet, Teachers Helping Teachers, and Pinterest.

Games & Songs

- “If You’re Happy and You Know It”

- ‘Feeling Face’ Charades

- Musical Emotions (like Musical Chairs but……)

- Feeling Scavenger Hunt

We can also use games and songs. I love using “If You're Happy And You Know It,” but I also expand out to,

If you're sad and you know it, you can cry.

If you're mad and you know it, stomp your foot.

You can include a variety of emotions with this song.

Doing feeling face charades with young children is fun and you'll get a lot of laughter when you play this game. Musical emotions is similar to musical chairs. A feelings scavenger hunt is where feeling boards are hidden around the classroom and children hunt for them. When they find one they make that face to match that feeling or they describe a situation that might make them scared.

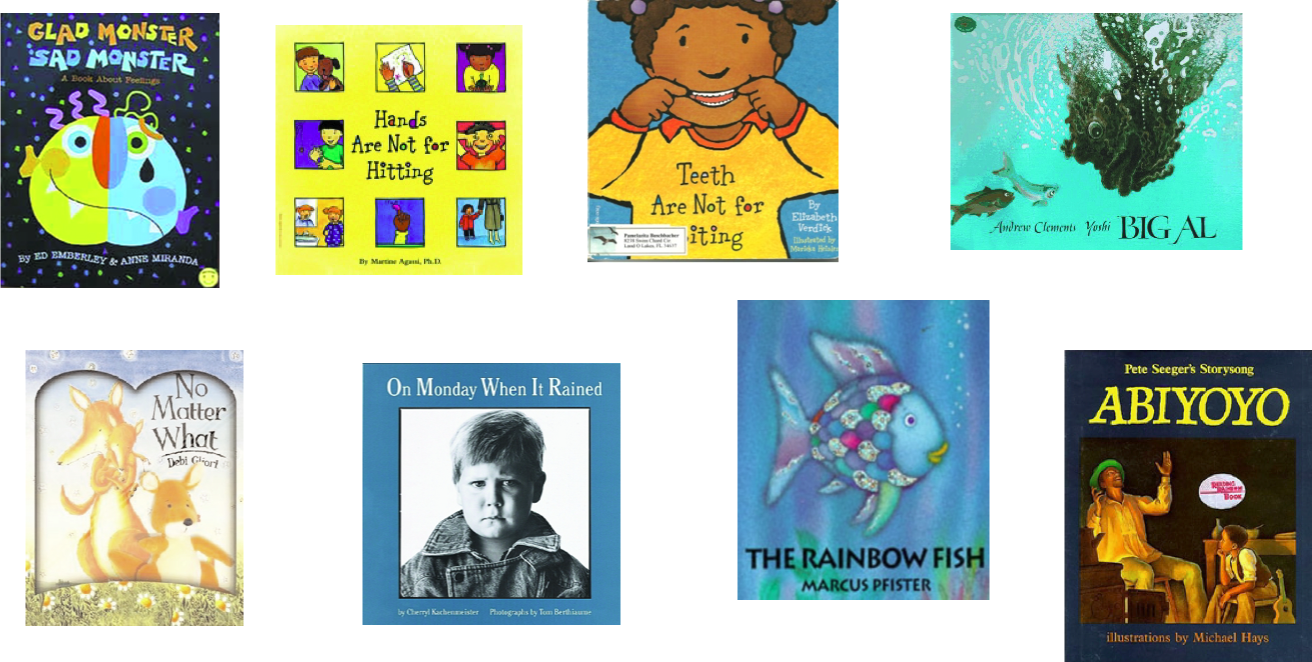

Social-Emotional Books

- Tell a good story in their own right and are well-crafted

- They are an easy and fun way to be more intentional about supporting social-emotional development

- Are written explicitly about feelings/behaviors

- Address challenging issues within a storyline:

- Directly as part of the storyline

- Indirectly by including coping/problem solving as part of the broader story

- In real-life situations

- Build feeling vocabularies and/or provide information about behavioral expectations

- Can provide information on friendship skills, emotional literacy, empathy, impulse control

- Can help children cope with a range of challenges: broken toys, friend not sharing, new sibling, sibling rivalry, moving, unemployment, deployment, incarceration, divorce, death

- Can help children generalize to different settings/people/situations

- Can be used as the starting point for a teaching experience

As I said before, we have a rich amount of social-emotional books that are commercially available. I have a library of probably hundreds that I've made myself for children. Here are some examples of books that you might find.

Figure 8. Examples of social-emotional books.

Figure 8 shows examples of commercially available social-emotional books. Hands Are Not For Hitting has a negative title, but the inside is all about what hands are for. Teeth Are Not For Biting is all about what teeth are for. The cool thing about these particular books is that at the back there's information for parents and for teachers about how to expand on the book. Again, on the website, challengingbehavior.org, is a list of books that have been proven to be very effective in helping children be able to express their emotions.

Figure 9. I Can Be a Super Friend!

Figure 9 shows one book that you can find at challengingbehavior.org titled How to be a Super Friend. This book was created by two friends of mine, Lisa Grant and Rochelle Lentini for a particular four-year-old who was having a hard time being a friend. They created How to be a Super Friend and actually had a cape that the children could wear when they were being a super friend. Here are some examples.

I can be a super friend. I like talking and playing with my friends at school. Sometimes, I want to play with what my friends are playing with. When I play, I sometimes feel like taking toys, using mean words, or hitting and kicking. My friends get sad or mad when I hit, kick, use mean words, or take toys. If I want to join in the play, I need to join nicely or ask to play with my friends' toys. I can say, "Can I play with that toy?" or "Can I play with you?" First I stop, then I think about what a Super Friend would do. Super friends use: nice talking, gentle hands and feet, look with their eyes, listen with their ears and take turns with toys.

Figure 10. Tucker Turtle Takes Time to Tuck and Think.

Figure 10 shows another book that has proven to be very helpful. Tucker Turtle Takes Time to Tuck and Think helps children deal with anger, which is something we all experience at times and all emotions are legitimate. This book was written by my good friend, Rochelle Lentini, to support a child, and it's been generalized to support a lot of children. Teachers have found it to be very effective.

Tucker Turtle is a terrific turtle. He likes to play with his friends at Wet Lake School. But sometimes things happen that can make Tucker Turtle really mad. When Tucker got mad, he used to hit, kick, or yell at his friends. His friends would get mad or upset when he hit, kicked, or yelled at them. Tucker now knows a new way to “think like a turtle” when he gets mad. (He gets hit, so he's mad.) He can stop and keep his hands, body, and yelling to himself! He can tuck inside his shell and take three deep breaths to calm down. One, two, three. Tucker can then think of a solution or a way to make it better.

You can have a little turtle puppet to demonstrate how he tucks his head in to think. This is a very simple book, but I've seen teachers use it in circle time to help teach children the skills so they can use the turtle technique effectively.

What are Social Stories©

Social stories© are short stories written in a special style and format for teaching social skills to young children (particularly, children with Autism Spectrum Disorder). They provide accurate information about those situations that they may find socially difficult or confusing. Research has demonstrated their effectiveness in teaching acceptable social and emotional skills.

Social stories have also been proven to be very, very effective. They help children understand situations that are sometimes very complex. They're written in a special style and a format for teaching those social skills. Again, you can find many on the web but, sometimes people don't always follow the rules. They're stated in a very pro-social manner and they are all about acceptable social-emotional skills. One that a teacher and I wrote was I Can Make Good Choices When I Feel Upset! I won't share that book right now, it's only four or five pages, but I will share it the next time in part two to give you a little bit more example.

Resources and Apps

- Children’s published books on emotions

- Emoji

- Emoticon

- Touch and Learn – Emotions

- ABA Flash Cards & Games – Emotions

- Emotions from I Can Do Apps

- Autism Apps - Choiceworks

You can find many resources that help with social and emotional literacy. Some are children's commercial or published books on emotions. There are a lot of emoji works out there, as well as app emoticons. Touch and Learn has an app on emotions. There are flash cards and games. There's so much more than there was five to ten years ago. The value that we place on children's social-emotional learning is very extensive now.

Adults Who Support Young Children’s Emotional Literacy Can Expect ….

- Fewer challenging behaviors

- Improved emotional self-regulation

- Larger and more complex feeling vocabulary

- More developmentally sophisticated and enjoyable peer social interactions

- Successful peer interactions

- Better problem-solving skills

We know that adults who support young children's social-emotional literacy could expect fewer challenging behaviors. They can expect that children will be able to regulate their emotions more effectively and they'll develop a larger and more complex feeling vocabulary. They will be more developmentally sophisticated and have more enjoyable interactions. Due to this, they'll be more successful in their peer interactions and have better problem-solving skills.

These are some additional resources I think that you'll find helpful as you go about implementing a lot of strategies in your classrooms and in your support for families.

- www.pyramidproducts.com

- www.socialstories.com

- www.do2Learn.com

- www.lessonpics.com

- www.challengingbehavior.org (Now called The National Center for Pyramid Model Innovations)

- www.freespirit.com

- www.csefel/vanderbilt.edu

- www.pinterest.com – Managing Behaviors & Social Skills

Three things that you can do to support children's social-emotional literacy, would be to

- Check out Resources for teachers at challengingbehavior.org

- Understand and enlarge your own emotional literacy skills

- Think of something else that you could do that will help carry over what<