Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Teaching Beyond Bars, presented by Quniana Futrell, BS, MEd, EdS.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- List factors surrounding incarceration that affect the child.

- Describe how to have non-stressful conversations around the sensitive topic of incarceration.

- Describe the significance of their role in helping these children and families.

Introduction

I am ready to teach you how to help and serve children who are impacted by having a parent who is incarcerated. In these situations, what does your role look like? Is this another job to do? Is this another hat you need to wear? No, this is just polishing the current role that you are in. In order to build that trust factor with you, I am going to give you some background information about myself. In talking about something that is so sensitive, I feel it is important to say that this is not only something that I have researched, but it is something I have lived. I grew up being a kid with two parents incarcerated. Primarily my mother who is currently dealing with some different things with the law, and so I say this to you just to truly earn my right to be heard by you is this: this is something that I live. I consider myself an empathetic expert on this topic and everything that I share today is not only something that I have read, learned about, and can prove but is also something that I have lived through. I want to help you not be afraid of this conversation so that these children can have a chance at life.

Resilience

My favorite word is resilience. I want you to really imagine a rubber band or a hair tie and how you can back pull it back. No matter how far you pull it back, it always goes back to its original form. Resilience is the ability of matter to spring back quickly into shape after being bent, stretched, or deformed. Resilience is also the ability to recover quickly from setbacks. We are all born with the ability to be resilient. For a lot of us, we feel that we have not bounced back quickly. However, I want to challenge you to know that you are resilient and you are born with this factor. When it comes to young children, they have it as well. However, if they are not welcomed into a conversation to talk about how they feel, that resilience factor can get stumped. I want to make sure that you know how resilient you are, as well as how you can help build that resilience in the young children that we serve.

Stereotypes

When we think about incarceration, what is the first thing that comes to mind after hearing a child say that their parent is in jail? I have been in atmospheres with some teachers who say things like, "I knew that was going to happen.” We have to talk about these stereotypes in order to reveal some of our hidden biases that are there. For example, just because a person ends up in jail does not necessarily mean that they deserve to be there. You cannot tell by the way they look that they were going to end up there because we never know. It could be that the ice cream man with the biggest smile ends up in jail. In terms of stereotypes, we want to make sure that you check yourself immediately, and this way your face lines up with what comes out of your mouth. Sometimes what we say does not line up with how we look and people can see through that, especially children.

Nearly three million children have a parent in jail or prison. I remember attending a conference, and I was talking to a guy about this and he said, "That's not something I have to worry about in my area." I responded by saying, "It's actually something that impacts a lot of children, so I want you to know that beyond what your community may look like, this is a topic on the rise. It is something that all of us must take time to consider learning about because you never know when you are going to come against something like this."

Can you group all children dealing with any type of trauma together? Absolutely not. It is something that has to be dealt with individually and prescribed differently. Everybody with a certain illness cannot all take the same pill and be healed. That is not the way it works because a lot of different factors play into it. Can this silent issue be resolved the same? How or why not? First of all, we have to make sure that we talk about the issue rather than staying silent. Many families will say, "What goes on in this house stays in his house." You have to realize and understand that the things that are not talked about never get resolved. When it comes to incarceration and its impact on young children, the only way to help is to allow them space to really talk about it. This silent issue cannot be resolved the same. Last but not least, how do we move past generalizing stereotypes? We do this by not putting all children in the same box because there are factors that play a different role in how children will be impacted.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

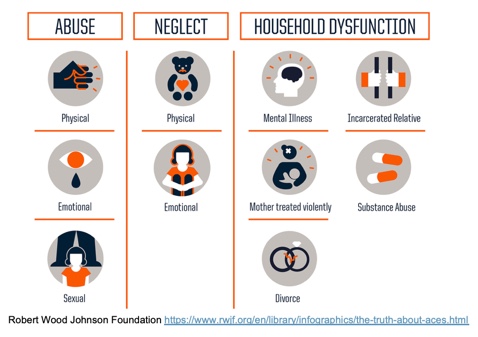

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are critical to how you will identify what you can do to help these children. It expresses the experiences that children go through that are adverse and traumatic. An example of this is abuse, whether it be physical, emotional or sexual abuse. Figure 1 shows an image outlining ACEs:

Figure 1. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

Research has proven that when children endure two or more ACEs, they have to seek some type of counsel or support in order to be successful in life. I am sure we have probably experienced two or more of these adverse experiences. However, we are still standing. But what about the next generation? It is heartbreaking to see so many young children commit suicide because they are going through so much. With this younger generation, they do not handle adverse experiences in the same way. We have to make sure that you are equipped to know what ACEs are, what they look like, and what they sound like so you can be quick to help them.

Here is an astounding fact about incarceration, according to a University of California, Irvine study:

"The study found significant health problems, including behavior issues, in children of incarcerated parents and also that, for some types of health outcomes, parental incarceration can be more detrimental to a child's well-being than divorce or death of a parent."

How can incarceration be more significant or detrimental than divorce or death? With divorce and death, there is a conversation that takes place. The answer or response from an educator is typically going to be the same: "What can I do to help you and your family?” When a child presents incarceration of a parent, will this conversation be the same, or is it going to be, "Oh, okay. Thanks for letting me know." Those who have not had incarceration as a part of growing up may not know what to say. In this case, saying less is better. If you have nothing nice to say, say nothing at all. Instead of saying the first thing that comes to your mind, which could offend or hurt the parents, say nothing or keep it short. That could be more detrimental than anything because they need you more than ever. We have to stop treating this conversation any differently than death or divorce. This is because it is important to understand the underlying factors of incarceration with recidivism and the unknown.

With a divorce, a child knows what has happened. It is typical that a game plan has been put together where the child can see more of one parent than the other, or they will see them both equally. With death, the person is never coming back. There are so many promises made that go into incarceration. “I'll never do it again. I am never going to mess up again because I love you too much.” After that, it may keep happening over and over again. With recidivism, or the tendency of a convicted criminal to re-offend, the person going to jail may promise something to a child, yet then go back. That back-and-forth is going to have a negative and emotional effect on them. Another impact on children could involve the police. Some hate the police. Children may be there to witness the arrests, and some may even want to go to jail with their parents. As crazy as that sounds, parental incarceration can be more detrimental than the other two situations because of the many underlying factors.

Factors that Affect the Child

- At which age the separation occurred.

- The child’s presence at the arrest.

- The stability of the family prior to the arrest, conviction, and sentence.

- The disruptiveness of the incarceration.

- The strength of the present child-parent relationship.

- The influence of siblings.

- One in 14.

The first factor is the age that the child experienced a separation. Was the child just born, five years old, or 13 years old? Based on the age, that is going to tell us the comprehension level and developmental ability that the child has to grasp the concept of what is happening. The child's presence at the arrest is such an important factor. If the child was present, they may be dealing with nightmares, bed-wetting, and replays of the moment. You also have to consider the stability of the family prior to the arrest, conviction, and sentence. If the child did not have a relationship with the parent prior to the arrest or conviction, the impact will be different from the child who grew up around them.

The disruptiveness of the incarceration is important because of recidivism. Who does the child live with, and where does the parent stay when they come out of prison? How much and how often is it disrupting the child’s life? The next factor is about the strength of the present child-parent relationship. If that relationship was not strong before the arrest, it will not impact the child as much once the arrest takes place. The influence of siblings is important as well. For example, let's say there are multiple siblings in one home. The oldest child now has to step up and take care of everybody, including doing their hair, cooking, and waking everybody up for school. This plays a huge role in how it is going to affect the children.

Prior to October 2015, the number of children in the US with a parent incarcerated was one in 28. However, in October of 2015, USA Today declared that there was one in 14 children in the US with a parent incarcerated. It is important to remember that the conversations about this topic are a concern for everyone. You do not know what that group of 14 children is going to look like to you, and there is going to be one that comes into play for you. This is a proven fact, so be ready.

Family Stressors

- Family is restructured

- Financial stress

- The unknown

We know that the child will be impacted, but we also have to take into consideration how the families are going to be affected. Once a parent is incarcerated, everything is restructured. Maybe one kid now has to stay with an aunt, the other with grandparents, and another with cousins. Everyone could end up in four different states while the parent is away. In the case of two parents incarcerated, you have to make sure that the children are accounted for. In some cases, one person in the family is not financially or mentally prepared to take on so many children.

There is a financial burden in this. For example, a collect call is expensive for families. Even when the family member wants to take the child to go visit their loved one, the cost and distance can keep them from doing so. This leads us to the unknown. What are the unknown stressors that the family could endure? Due to underlying factors, the family has to deal with the stress of children and finances, as well as the emotional and physical stress for family members outside of the affected household. It is not always as easy as letting the child stay with their grandmother.

After considering all of this, now what? What is your role as a professional? How can you serve these children and their families? Remember that we are a community first, and you are the one they look to for answers. You are not a therapist, judge, or lawyer, but you are a resource in the community. You have the knowledge and the ability to get resources for these families all at your fingertips.

Parent Explanation

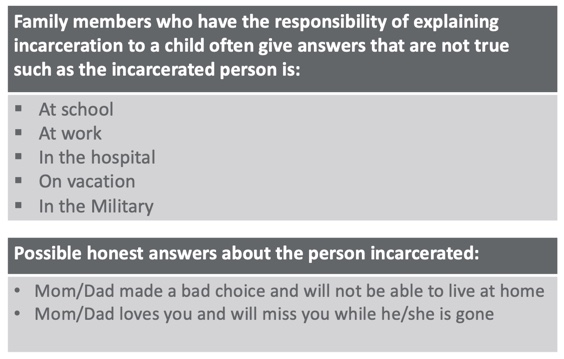

Figure 2. Parent explanations of incarceration.

Family members who have the responsibility of explaining incarceration to a child often give answers that are not true. I have heard people tell a child that the incarcerated parent is at school, work, the hospital, on vacation, or in the military. I was teaching a class in jail, and a young lady said to me, "I don't want my child to worry, so I told her I was in the hospital." When I asked how long she had been in jail, she said, "Six months." I responded by saying, "You don't believe that your child is concerned with her mom being in the hospital for six months?" When I said that, she sat back in the desk and said, "Wow, I never even thought about that." It is easier for adults to give a false answer because they do not know what to say at the right time.

There are possible honest answers about the person incarcerated. For example, the child could be told about how their mom or dad made a bad choice and will not be able to live at home. One of the things I share in my book called "Our Moms" is how you can have this conversation. Explain to the child that their parent is in a place called “jail,” and they get food and a bed. You can tell them how they have access to a TV, so they can watch some of their favorite shows. Tell the child how they do not get to live with them right now, but they will be back soon. One of the key factors that parents have to realize is that there is no definite date that they can give to return home. When the child asks you about a date, you say, "I honestly don't know. We can keep writing and drawing pictures together for as long as it takes. When they come home, I know you'll be so excited." See how quick we are able to flip the script and turn the conversation back around? The conversation should not confuse the child or give them false hope. That is one of the worst things we can do in this type of situation. Again, you are the resource. You have to present yourself as such.

Role Play Scenarios

Scenario 1

Let's role play a bit. The first scenario is about a class of preschool-aged children and their teacher during a circle time. Everybody is talking about how they went away to the beach over the weekend, visited their grandma's house, had their favorite meal for dinner, or went to see a movie. However, one child says, "I went to visit my daddy in jail." What is your response? Here is what it should be: "You went to see your dad in jail. Oh my gosh, how was it?” Wait for their response, whatever response they give you. It was nice, it was far, it was cold. They have vending machines. Whatever their response is, you will follow it with, "Wow, that's great." Leave it at that, and then move onto the next kid. You are not there to put them on the couch and take their worries away. I wish we all could, but we cannot. This way, you will build the confidence to have that conversation. I have heard many teachers just say, "All right, next." Do you see how saying that dismisses the child? Think about this for a moment: do you know what it feels like to be overlooked or dismissed? It is not a good feeling. It is not good for this child either, because then they think about how there is another adult who does not get it. You want to provide a safe space for the child.

Think about your vision. When you decided to pursue this career, did you want to change lives? I am sure that it is not because of the pay. Your reason has to come from a place of purpose. If you have not asked yourself about this recently, now is a great time. What is your “why” for being in this field? Taking the extra leap to help these families must come from a deeper place. Therefore, help that child who says, "Last night my dad went to jail," through asking them about the experience. See if they want to draw a picture or write a letter about it. Do not allow the situation to be something that is a disease, or strange. When this happens around the other kids and everybody wants to know what jail is, minimize it as much as possible. Give a clear statement, such as, "Jail is just a place where certain people have to live sometimes.” This is for the sake of the whole class, just to keep moving with the conversation.

Scenario 2

The next scenario is about a teacher and a preschool-aged child who visited dad in “college.” The child says, “Last night I went to see daddy in college, and everybody had orange jumpsuits.” What we have here is a flat-out lie. This is the type of scenario you do not want to be in because this is where many of your families will fall. There are more families prone to lie to these children than there are families who tell the truth. In this moment, is it your role to go ahead and let the child know, "Thank you for sharing, but your daddy is not in college. Your dad is in a place called jail, just so you know"? Absolutely not. Ask yourself this: is there ever a perfect time to tell the child the truth? Is there ever a perfect time to talk about jail and incarceration? Is there a perfect time ever to talk about that? The answer is no. There is never a perfect meal, or a greater amount of money you could spend to make this easier to tell them. Children will be emotionally impacted when this is shared with them. The only way you can do it is to be honest. If you are this child’s teacher, your role in this is to say, "Oh my gosh, really? Was it a bright orange or a darker orange? Was it like this orange crayon or this orange marker?" Allow the child to elaborate, ask if they liked the visit, then leave it at that. After that, there's definitely a conversation that has to be had. We will go back through both of those together so that you can know what to say even after that point.

Scenario 3

Here is our last scenario: speaking with the parent or caregiver after the child exposed the family secret. The first scenario was about the child who shared that they visited their dad in jail. The second scenario was the child talking about their dad being in “college.” After these scenarios, how do you now present this information back to the family? How do you take what was shared with you and make sure that the child is safe, but still communicate with the family? Let's talk about the first scenario. I got through the moment with the child and did not embarrass them. I asked them how it made them feel and had them draw a picture about it. Now, here is what you do. You take that picture and put it in a beautiful envelope. When they get picked up, find their parent or caregiver and say, "Excuse me, do you have a moment to talk? I promise it is going to be brief." That is when you start this sensitive, well-needed conversation. Explain that the child mentioned how their dad is in jail during the class share moment. Say to them, “I know that you and I haven't talked about it yet, but I wanted to mention that she said that."

After that, you will get one of two responses. The first one could be, "Yes, that is something we have been going through. It is something private, and we did not want everybody to know." The other response could be, "What, jail? Oh no, he is just at work." In order to play both, you say the same thing. "Okay, I just want you to know that if indeed there's ever a time, I can be a resource for you. I have some flyers, some books, and pamphlets that I can give to you about this particular topic. I would love to be a resource and share that with you, so just let me know. Have a great day." All you do is present yourself as the resource. You give them the tools, then you leave it alone. Nothing more, nothing less.

One of my favorite things that saves everybody in life and in business is documentation. You want to document that conversation in order to let your administration know that it took place. Is this something that you want to spread around the entire facility? The answer is no because there needs to be confidentiality, and you want to make sure that you stay true to that. You do not want the entire school to know the personal business of this family. You also want the family to be able to trust you. They may have told you the dad was at work to see what your response would be. You need to keep this on a need-to-know basis, so families are not embarrassed by something like this.

Let's take a look at scenario two. This is when we talked about the child visiting her dad in college. You asked the child questions about the visit and moved on with the conversation. When the caregiver arrives after school, say the same thing. "I just want to let you know that your child shared that she visited her dad in college, and everybody was wearing orange jumpsuits. I’m not sure if maybe at his particular college it’s a uniform college, but I know to me it sounded like it could have been anything else. I just want you to know that I'm a resource for anything that you could need dealing with any type of childhood experience that could be new to you or your family to help you really talk to the child so that they can really grow through whatever it is that could be potentially going on." Again, you will get one of two responses. The first one is, "Oh my goodness, thank you so much. We didn't know what to tell her. I just didn't want to scare her." Then you say, "Yes, I understand that completely. I have pamphlets and websites that are filled with different programs in this area. If you need my help with anything, please feel free to let me know.” Leave it at that because all you are doing is making them feel comfortable and presenting yourself as trustworthy.

Let's talk about when the caregiver says, "No, if she told you that they are in college, they're in college. They just happen to wear orange jumpsuits. I don't understand why you're talking to me about this." Your response to that will be, "Okay, I totally understand. I just wanted to let you know that I am a resource in case there's ever anything that you guys may need. If he's in college and they're wearing orange jumpsuits, there's a difficult subject that could come up. If I can't help, I'm sure I know somebody who can." Go along with the lie because it is not your job to transform their mindset at this time. They also may not be ready to talk about it yet. The fact that a family member is now incarcerated is not something the family wants to talk about to you, their priest, pastor, therapist or anybody. Know that even if they do dismiss your help, still offer it. You are still the one who is equipped to help this family. Whether they dismiss it now and take it up later, at least the seed is planted. I want you to know and feel confident in these different scenarios regarding teacher-caregiver conversations. It is a simple conversation. It is a big deal for children, but it is a simple conversation between two adults.

A Word of Encouragement

My motto in life and business is, "Change the family, change the world.” When I originally started out in business, I remember thinking, "I just want to help families and change this world. I have to help them see that if you take the time to help your neighbor or family member, it would alleviate the crime in our communities and change our world for the better." With social media and the news, we are always seeing some type of injustice happening. From this moment forward, I want to challenge you to think about what would have happened if a person who committed a crime would have grown up in a healthy environment. What if their family was present and did not just provide them with presents? Instead of the criminals or addicts that they have now become as their coping mechanism, what could they have been? I want you to know that we can change the world, but it all starts with changing family.

One of my favorite quotes by Frederick Douglass is, "It is easier to build strong children than repair a broken man." Simply put, it is going to be more difficult to unravel all the years of experiences a broken man has had to live through. With children, we still have a shot. I urge each and every one of you to consider changing the next generation in your classroom because they are your family. These are your babies and you love them like they are your own. We need to have conversations like this in order to learn how to teach beyond the bars of incarceration and not continue to look at it as this topic we cannot discuss. Break down the wall of your stereotype and tap into some of your own biases that you may have. In order for us to truly make a change, we have to make sure that we can change the families within our classrooms today.

Summary

I am glad that you listened, and that you will take this information back to your school and start a wildfire. Do this so we can get everybody ready to teach beyond bars. I am known as the Children's Champ, serving children who are dealing with parents who are incarcerated and building champions by healing the inner child in many of us. I want you to remember that you are a champion in your classroom. I want you to do the work that is required to build other little champions that come into contact with you. Teaching beyond bars is not beyond your reach. It is something that you are capable of doing each and every day.

References

Genty, P.M. (2012). Moving beyond generalizations and stereotypes to develop individualized approaches for working with families affected by parental incarceration. Family Court Review, 50(1), 36-47. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1617.2011.01426.x

Parke, R., & Clarke-Stewart, K. (2011). Effects of parental incarceration on young children. Retrieved from http://aspe.hhs.gov/hsp/prison2home02/parke-stewart.htm

Turney, K. (2014). Parental incarceration linked to health, behavioral issues in children. Retrieved from http://news.uci.edu/press-releases/parental-incarceration-linked-to-health-behavioral-issues-in-children/

Walker, A. J., & Walsh, E. (2015). Adverse childhood experiences: How schools can help. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 28(2), 68-69. doi:10.1111/jcap.12105

Citation

Futrell, Q. (2019). Teaching Beyond Bars. continued.com - Early Childhood Education, Article 23614. Retrieved from www.continued.com/early-childhood-education