Editor’s note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Trouble with Transitions? 5 Essential Ways to Prevent Challenging Behavior, presented by Barb O'Neill, Ed.D.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- List 5 strategies for setting up successful classroom transitions

- Describe how visuals can be used to provide additional support to a child who has difficulty transitioning.

- Identify 3 common mistakes teachers make when offering children choices during transitions.

Introduction and Overview

Thank you for joining me today. This presentation discusses classroom transitions, specifically for children ages two through five. You may have a perfect vision of your classroom that your children are lined up like little ducklings in a row, and they would go with the flow and move through the day, peacefully and orderly, from one activity to the next. However, like most teachers, you probably know that is not how it happens most of the time. If you've been in the field a long time, or if you have a lot of strategies in your toolbox, transitions may occur smoothly for you. However, given the nature of young children and their developmental abilities, it's not a failure on your part if transitions are not as smooth as you would like. If some of the children are trying to go off and do their own thing or they aren't listening, that is perfectly normal.

When I was new to the field 25 years ago, I still remember the first day that I tried to lead the children to clean up and go to the rug for circle time. It was such a failure; I cannot even begin to tell you. No one was listening, and no one was cleaning up. Even though I had been an assistant teacher in that classroom, when I was supporting the lead teacher, I felt like I was helping make it happen. I sang the same song, I did the same sequence of things, but it just fell apart that day. At that point, I became very interested in what we can do to support children in these classroom transitions. Today, I am going to share five strategies that I have found to be effective. Some are from the world of ECE (early childhood education), some have a musical flair, and some are from the realm of special education. There are many other strategies, but I'm going to highlight the five that I think will help you the most in creating a foundation for transitions in your classroom. You can use these in many different ways, tailoring them for your unique circumstances.

Five Strategies for Transitioning

You're probably implementing some of these techniques already, so I'm hoping to build on what you are already doing. We can use the following strategies to help with more successful classroom transitions:

- Give Transition Warnings & Individualized Support

- Sing/Chant the Directions

- Use Play and Children’s Interests

- Choose Your Words

- Use Visuals

I will also share a bonus strategy with you at the very end.

1: Give Transition Warnings and Individualized Support

In the early childhood education field, classroom teachers are usually pretty good about giving some type of warning that a transition is coming. Even telling the children "five more minutes until clean up" is probably helping some children to get into the mindset of cleaning up and moving to the next station or activity. However, many children exhibit challenging behaviors during transitions (e.g., hitting, kicking, throwing things). If you see these behaviors during your transition, it may be because you don't have a strong enough foundation of support. You can increase your class-wide foundational support for smooth transitions as a group, and then implement some individual supports as needed for specific children, without a specialist necessarily coming in to write up a behavior plan. Let's look at some techniques that will help everyone with transitions.

First, instead of simply giving a single, verbal 5-minute warning, give the entire class a 10-minute, a 5-minute, and a 1-minute warning. In my experience and observations, when warnings are given at those three intervals, children tend to be more prepared to transition. This is especially helpful with the transition from the playground or free play time (where children are engrossed in self-directed play and activities) back to the classroom. In those situations, they may be more reluctant to clean up and move on, because they are highly engaged in what they're doing. Simply by adding two more reminders, one earlier and one later, in many cases you will start to see more children who are ready to clean up with you and move on. My recommendation is to use 10, 5, and 1. Some classrooms give warnings at 10 minutes and 5 minutes, then they do a countdown backward from 10 through 1, and then begin to sing the clean-up song. This is something that is easily implemented. It's just a matter of getting into a new routine.

For some children, these group warnings might not be enough. I would advise putting the reminders in place first with your large group, and then you can add extra support for the individuals who need it. Who could benefit from additional reminders? Anyone who you see consistently not cleaning up when you say it's time to clean up or children who are running away on the playground when it's time to come in. If you are with more than one teacher, you can decide who will give the group reminders, and who will give the individual reminders. If you'd like, you could use a timer, such as an egg timer or anything with numbers. You can go to the dollar store and get something that you think the children might be attracted to. You can use this timer with the whole group, or you may want to get certain children their own timers. They might like to watch the timer, and they could even help you set it. That added support of an adult coming around and telling the children can assist with moving through their transition. You are going to have to commit to doing it consistently for probably at least two weeks before you're going to see the results.

Decide which person in your classroom would be best suited to give the 10, 5, and 1-minute warnings to the whole class. If you are the lead teacher, but you are not very good at keeping track of the schedule, perhaps your assistant is the appropriate choice to initiate the 10, 5, and 1. In the beginning, when you are first implementing this strategy, you may find it useful to set a timer for yourself to remember when to initiate the warnings, so that you are sure to follow through.

After you have fully implemented the group warnings, determine which children still require individualized 10-5-1 minute warnings. You may find that some children are doing better simply with the additional group warnings. However, you may still have some children who struggle with transitions. They can be anxiety-provoking and cause challenges for some children. Whatever the reason, they may just need that extra support.

Who would be best suited to administer the individualized reminders? It usually works best for one adult to do the group 10-5-1-minute warnings, and another to do the individual reminders. Some teachers like giving the individual warning to almost all the children. Sometimes, it ends up being in little groups of twos and threes, wherever the children are located.

How can you deliver these reminders to the children so that it's motivational? Honestly, do any of us really like to clean up? I know I don't. I tend to clean in inconsistent bursts. However, if I'm having company (e.g., a dinner party), that is motivation for me to put the dishes and the laundry away. If I know that a fun event is to follow, and my guests are coming for dinner, I'm motivated to clean. Similarly, it is helpful to find something motivational to encourage the children to help clean up, so they can transition to the next fun activity.

2: Sing the Directions

As ECE professionals, you are probably already singing in your classroom. Perhaps you sing "The Wheels on the Bus," or "The Itsy-Bitsy Spider." You may already be singing the directions during clean up time. In my experience, this is an underused strategy. It's not that teachers aren't doing it; it's that you could be singing to the group and individually much more than you are. The brilliance of this technique is that when you sing the directions, and you sing the same thing two, three, five, or eight times, you don't get as frustrated as you do when you speak the directions, and the children don't immediately jump into action. I was working with one teacher, and I suggested that he sing the directions. He reported back the next week and he said, "I'm not sure if the children are more on task, but I'm singing through all the transitions and I feel so much better." If you sing the directions, the teachers, as well as the children, can have a more joyful time. It may take just as long, or, in some cases, it will help them move through more quickly, especially if you're using the strategy in conjunction with other strategies.

Piggyback Songs. Piggyback songs involve using familiar tunes and embedding the directions within the song. I have to confess to you, I just learned this term last week, although I've been teaching this technique for years. For example, it could be "The Farmer in the Dell," or "If You're Happy and You Know It," and you simply change the words to suit your needs. As far as I'm concerned, you need at least one piggyback song, and you don't need to be talented.

One example of a piggyback song is the "1, 2, 3 Song." I was working with some teachers and they were using this all throughout the day. It worked beautifully and it's so simple.

1, 2, 3 let’s march inside, march inside, march inside

1, 2, 3 let’s march inside, so we can eat some lunch

1, 2, 3 put your jacket away, jacket away, jacket away

1, 2, 3 put your jacket away so we can read a book

You don't have to march; you could say "go" instead, but marching makes it a little bit more fun. You would sing this several times, of course, because it's going to take a little while. Make it fun. You could have the children waiting by the door jump up and down while you are waiting for the stragglers to arrive. When you finally get all the children gathered together, march inside. When you get through the classroom door, sing "1, 2, 3 put your jacket away, jacket away, jacket away...so we can read a book," incorporating that motivational element. If you have younger children, or it's the beginning of the school year, you might have to be more specific with your directions and sing "1, 2, 3 unzip your jacket" or "Put your jacket in the cubby...so we can read a book." You can adapt the words all day long to suit your needs.

Another example of a piggyback song you can use is to the tune of "If You're Happy and You Know It." For example:

Put your jacket in your cubby, in your cubby

Put your jacket in your cubby, in your cubby

Put your jacket in your cubby, and make sure it's nice and bubbly

Put your jacket in your cubby, in your cubby

You can make silly rhymes (e.g., use words like "bubbly" or "snugly") or you can choose not to rhyme. Sometimes the children will help you come up with a song, or they'll start singing their own versions. Some of your rhymes might not make sense, but it doesn't matter. Just come up with your tune and try it out.

Here is another song you can use:

10 more minutes till clean up, clean up, clean up

10 more minutes till clean up and then we'll read a book

You can customize the words in this song to suit your needs. For example, you could sing "10 more minutes till we go inside, go inside, go inside," or, you can change the words to "Now it's time to eat our lunch...Don't forget to wash your hands."

Speaking of washing hands, you might have some children who linger at the sink. From a self-regulation perspective, some children crave sensory input and some children do not like it. For those who love the sink, washing hands can feel soothing. As adults, many of us enjoy soaking in a bathtub or swimming. We don't need to have an official diagnosis of sensory integration, however, keep in mind that some children may be calming themselves down when they wash their hands. Rather than getting into a power struggle over it, I would urge you to give them an extra minute or two and sing a song about it.

This is the way we wash our hands, wash our hands, wash our hands

This is the way we wash our hands, we get them nice and clean

This is the way we wash our hands, wash our hands, wash our hands

This is the way we wash our hands, and then we get a towel

This is the way we dry our hands, dry our hands, dry our hands

This is the way we dry our hands, and then we throw it away

Sing it a few times before you ask them to move, and then sing the directions to help move them through the transition. You may have to sing that song eight times, and that's okay. You could start to sing the song a little faster so it gets quicker over time. You can sing them right into lunch, or the next activity. Similar to the last strategy, you sing your songs with the whole group, or with individual children who need that extra support.

Who do you want to use this with? Are there some transitions where a number of the children are having difficulty? Do you want to sing the directions for your whole group, or do you feel that most of them are doing fine, and you only have one or two children that need extra support?

Decide how you want to begin singing the directions, and for which transition(s). Select your transition, your tune and your words. Perhaps you want to start with the bathroom and hand washing. Maybe you can sing about cleaning up after lunch and transitioning into nap time. You can use the same song throughout the day, and change the words to suit your needs. You can try it with individuals, or your entire class may benefit from singing the directions. If you see that some of the children are not singing along, or they are responding negatively to the singing, this is not the correct strategy for those children. Fortunately, there are more strategies to choose from.

3: Use Play and Children's Interests

If you're in the ECE field, you know that children love to play in their early years. Why not capitalize on their propensity for being playful to motivate them, and help your transitions go more smoothly? That's good for them because they're learning to listen to the teacher and to be with the group and act as expected for school. We can use play to help children learn those skills that they need to succeed in their later schooling and in life.

In terms of building on children's interests, when learning something or being asked to do something that a child finds interesting, that will motivate a child more than someone simply telling them what to do. Ultimately, this is about showing children that their interests are important and valued. When relating to other people, it is respectful to take an interest in the things and activities that they like. Ideally, we want to build our classrooms in a way that's going to be meaningful and motivating for young children.

If you make your transitions playful, that's going to resonate with the group. For example, when you come in from the playground, you could all pretend to be airplanes, or when it's time to clean up for lunch, sing a fun clean up song. However, right now I want to focus on the individual child who has a lot of behavior issues. Maybe they are the one getting stuck at the sink. Other than that, they don't seem interested in anything. I have heard many teachers tell me that building on a child's interests is a good idea in theory, but they have a child who is not interested in anything. The child is always flitting around, without much of an attention span, acting out at circle time, and generally not engaged. What I have found is that when we stop focusing on the negative, and we look closely with a positive, strength-based lens, we can usually find something that resonates with that child.

I worked with a teacher who had a child in her classroom, and the only thing that she could determine that he liked was playing at the sink. For that child, since we know he likes water, I recommended filling the sensory table with water so he could play and splash. You may have a child who is constantly flitting and running around the classroom. Running is an interest that we can build on, possibly during large motor activities or on the playground. If you know a child who resists lunch every day but loves milk, for example, maybe you can talk about milk as you're transitioning. Maybe the child doesn't have a broad repertoire of books they like, but they do like Pete the Cat. Perhaps we can read that book to the whole class at a time when the child doesn't want to transition. We could obtain a second copy of the book, and if the child is resisting nap time, he can have the book for his nap time or a book from home that he might love.

One special case was a child who liked to go around the classroom and act like he was a dragon breathing fire on everyone. That behavior demonstrates that we might need to help him initiate play in other ways. In order to get this little boy to come to circle, we decided to build on his interest in dragons. The teachers started with a large group gross motor activity, and they sang the Dragon Hunt song. The other children loved it, and the boy did end up becoming interested and joining the circle. Another idea would be to have a little toy dragon who can fly down and help you through transitions. You could also read books about dragons. Infusing dragons into the curriculum successfully helped that child become more engaged more of the time.

We had a little boy who had a lot of difficulties gathering with the class. They lined up to go outside. Once he got out there, he loved it, but he really struggled to get his jacket and find his way back to the line. What they decided to do, in addition to singing some of those directions, is to tell the child that he could hold the bubbles to go outside, which worked great. You might say, "Well, everyone is going to want to carry the bubbles" or "That's not fair." You could handle that in a couple of different ways. You could get bubbles for every child to carry, or if you have a few containers of bubbles, you can have the children take turns carrying them. Or, they can carry different objects out to the yard, so that everyone has something to carry. You could simply tell the other children that Kevin needs to hold the bubbles so that he can stay in line and get outside safely. If you've been having regular power struggles with that child, the other children know that he needs extra support, so you don't have to get into a big discussion about it. Just state very quickly, "Kevin needs to hold that to get outside with us safely," and then redirect the conversation to ask them what they are going to do on the playground. As the teacher, you don't need their approval. You are making an executive decision that this child needs something. You're going to tell them very matter-of-factly, and then you're going to move on. Most of the time, the other children will go along with it.

The last child we will talk about, Brandon, started to pretend that he was a cat. This particular child really struggled with self-regulation and moving through transitions. The teacher, instead of telling the child to stop pretending and clean up, she simply said, "Okay, kitty -- clean up your toys so we can go outside." She said this all day long and it worked like magic. This child also frequently resisted joining the group for art. One day, they were making dragons. At first, this boy wasn't interested. The teacher said, "Brandon, come over and make a cat dragon." He went over to the table for the first time. Using those interests, no matter how small they seem, can be so powerful in motivating a child.

Who do you think would benefit from this type of interests-based support? For which transitions do you think it would be most helpful? Is it the clean-up, or is it getting to nap? Which of their interests could you explore? Make sure you take a minute to make that web of their interests, or just brainstorm in a list form.

4: Choose Your Words

As teachers, we often ask children to use their words to express themselves. Similarly, we should also be choosing our words carefully. There are many common mistakes that early childhood teachers make when choosing their words. I know that I am guilty of these mistakes, even when I have been doing trainings and presentations. We will uncover some of these common errors, and offer some alternative words and phrases that may be more motivating for children.

One common mistake that I often hear teachers make, including myself, is ending a sentence with the word "okay?" Listen to the following sentences:

- It's time to clean up now, okay?

- It's time to go outside, okay?

- We're going to lunch now, okay?

When you are not offering the children a choice, and you are giving them a specific direction, ending the sentence with "Okay?" makes it seem like they have an option. When you return to your classrooms, be cognizant of ending your sentences with "Okay?" If you are not offering a choice, avoid using "okay?".

Another common mistake is offering unclear choices, or just offering one choice. You may get by with that sometimes, but what I recommend is that you offer two clear choices. Parents and teachers alike like should offer children choices, but we need to be very specific. For example, instead of asking "Are you ready to clean up now?", say something like "Do you want to clean up the long blocks, or the little square blocks?" If they start to argue about who is going to clean up the rectangles, let them resist within that structure. You're offering two choices so they can come up with a third. It's not that you have to only let them do these choices, but you want to put two very specific ones out there because if you stop and wait for them to choose, it's too much pressure. Another example would be giving the choice between two books: "Do you want to read Pete the Cat or Abiyoyo on your mat?" Or, if they are eating lunch, you could ask, "Are you ready to clean up now? Or do you want to eat for 5 more minutes?" If the children are slowly transitioning from the lunch table, it might be okay to give them five more minutes, remembering to be very specific.

The third common mistake that I often see is when teachers say, "You need to clean up." I'll give a little bit of a caveat on this: if it's working great, that's fine. The children do need to take care of themselves and the materials. I don't have a philosophical concern about using the phrase "you need to," but if it's escalating into a power struggle, you may want to try something new. Instead of saying, "You need to," try saying, "Let's." If you phrase it as, "Let's hurry up and put all the blocks away so we can go outside," that kind of puts you on a team with the child. It's our classroom community: we are in it together. "Let's" keeps things in the "we" mode. It breaks out of that power struggle and keeps things upbeat. Another good phrase for teachers to use is "it's time to." You are referring to the schedule you need to keep as a class. "It's time to eat lunch." You could even show them a clock. It's not on you as an adult authority figure; it's on the routine.

How will you use this? It's hard for us to be aware that we're making these mistakes. If you know you do say "Okay?" at the end of sentences, for example, then you can decide to say "now" or "five minutes." In order to become more aware of what we are doing and saying in the classroom, we could ask a colleague to keep tabs on us. Another method would be to make an audio recording in the classroom, then play it back and listen to it. I know that might be painful, but it is useful to find out if you are making any of these common word choice mistakes.

5: Use Visuals

As the saying goes, "A picture is worth a thousand words." This holds very true for children who are visual learners, and even those that aren't. We talk to children all day long, giving them instructions, directions, and modeling vocabulary. Sometimes, I feel like all they hear is the teacher from Charlie Brown saying, "Wah wah wah, wah wah wah wah" (for those of you who know the Peanuts gang cartoon). It is extremely helpful to use visuals to help support children to move through transitions during the day. Let's look at some ways that we can use visuals in the classroom

First, you probably already have a classroom schedule posted on the wall in your room. The question is: Are you using it? I find the schedule is the easiest visual for most teachers because they already have one. Let me give you some examples of how to use the schedule.

When you are transitioning the children to circle time, make sure that you are showing them the pictures of what's coming up next. You can combine this with singing directions:

Now it's time for circle time, circle time, circle time

Now it's time for circle time, play time is done.

If your schedule has pictures on it to represent all of the day's activities, remove the picture as you complete each one. For some children, this helps them with their "out of sight, out of mind" mentality. Some classrooms have a visual schedule where they put a clothespin on the time of day (e.g., lunchtime), and when it's over, you can take off the clothespin and move it to a different activity. When you go outside, I would recommend taking the schedule or the pictures with you. That way, you can show the pictures to the children who need individualized support, you can sing the directions to them, and they know what comes next.

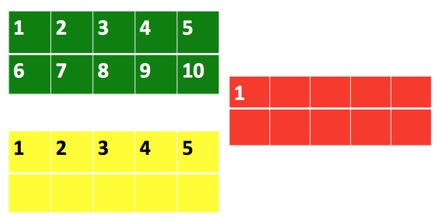

Another visual that works great is a visual support for 10, 5 and 1-minute cleanup warnings (Figure 1). This works in conjunction with the 10-5-1 strategy. Here, you can see the added element of green means "Go, you get to keep on playing," yellow means "Start to slow down and wind up," and at red 1 minute lets the children know they have to stop. You can even have one of the children help to hold them up.

Figure 1. Visual support for 10-5-1 minute warnings.

Additionally, another technique you can use is to show the children something they have to look forward to. For example, show the children their favorite book so they know they can take it to their cot, or they can bring the book to read outside. That way, they have something visual to know it's going to be exciting. Perhaps they aren't interested in books, but they like puppets. Maybe you want to bring a puppet out, and keep it in your first aid backpack. The puppet can come out and take a peek around the playground, and you can tell them that the puppet is going to visit at circle time. Going back to the dragon example, you can bring a little something special and say, "Look who's going to visit us at circle time today." You can use one of your objects for the circle time, bring it over to where they need to clean up or bring it outside, and then just tuck it away. Make it exciting and intriguing for the children.

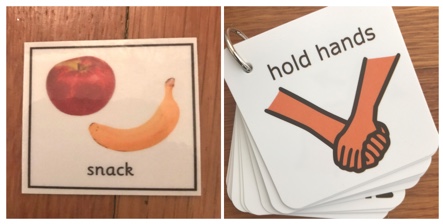

Next, use visuals with the words "first, then" or "now, next." This helps children know what we're going to do first/now, and what we are going to do then/next (Figure 2). For example:

First, we clean up; then, we have circle time.

Now, we eat breakfast; next, we play with toys.

These are Velcro, so you can switch it out and that way you can use it throughout the day.

Figure 2. First, then; now, next.

You can also just use visuals by themselves (Figure 3). You can take your lunch picture out to the playground. You can make special ones, or download them off the internet. You can just use icons, or you can take photographs of the actual objects and print them. If you'd like a few pictures of certain directions or objects, you can laminate them and put them on a ring. If you're a jeans wearer or pants wearer, you can clip it to your belt loop. This is from the world of special ed and can be used for children who have individualized education plans (IEPs), but it's a great support to anyone who needs it. Again, you can sing the directions and show them the visual:

Now it's time to go inside, go inside, go inside

Now it's time to go inside, find a friend and line up

Figure 3. Pair a picture with your words.

Where could you use these visuals? Do you have some children who have a hard time transitioning indoors from being on the playground? How can you give them a visual that will be supportive? What would motivate the children, whether it's one child or a small group? You could bring out Harriet the puppet and give the children a sneak peek because you know they love her. Maybe you are going to sing that dragon hunt song, and you could just bring a picture of the dragon. If you simply tell them you're going to interrupt their play to go inside for circle or for the dragon, it might not be compelling enough. However, if you are showing that picture, that grabs their attention.

6: Bonus Strategy: Don't Transition

One final strategy to consider is to think about whether you can eliminate any of your transitions. Transitions are hard, especially if you have children who are having trouble. Perhaps you can minimize some of the transitions. Let's say normally, you have nap time, snack time and play time in that order. If you are struggling to get some of your children to eat, what if you combined play time and snack time? Think about other times of the day where you could reduce transitions.

Your knee-jerk reaction may be to say, "We have to do it this way. We've always done it this way. We can't stay out on the playground..." I understand that there are some pragmatic concerns. One of the trainings I do is on a fixed versus a gross mindset. In a nutshell, the fixed mindset is when you focus on all the reasons why this strategy won't work for you, why you can't minimize transitions. As we look at this next scenario, I invite you to put on a gross mindset.

Imagine if there were no snack time? What if there was just snack and playtime and the children had a choice. You might argue that at your facility you have a food program, and every child has to be offered food. But, you could have an optional snack time, where the food is available and served family style. The children are able to serve themselves. One of the teachers would go around and make sure everyone gets offered a snack. You may want to supplement that, especially if you're working with two-year-olds. Ask if they want a snack. If not, make sure they know it will be put away soon. They will learn to make a choice. It caters to a child's bodily rhythm; they can eat if they are hungry. Some children may like to resist adult authority, and they enjoy the attention they get from resisting snack. This would minimize that power struggle.

Imagine if children could save their creations? You may have children who resist cleaning up their blocks. That is a justifiable concern. It's sort of like they made a beautiful drawing and then someone ripped it up or threw it in the garbage. Two-year-olds don't care so much, but at age four and five, children can make elaborate block structures. What if you left it standing? Your fixed mindset might be to say, "No, we have to clean up, because there's another class in the morning" or, "No, because we need to put the cot there for nap time." Let's think about it using our gross mindset. What if we took a picture of their creation? You could build literacy by having them write their name on a piece of paper and take a picture of their block structure to "save" it. You could suggest writing a letter to the morning class to see if it will be okay to leave it up, and then will we let them play with it, or we could ask them not to touch it. If you are using smaller, manipulative blocks, you could have them build on trays, and that way you could carry the tray and put it on the top of the shelf with their name on it.

What if there was no toddler circle time? What if you sang songs or read a book, but you left the toys out? I think that's developmentally appropriate for the age. I worked in a facility that had a toddler program. The children arrived, they had snack, then playtime, then they sang songs and encouraged the children to come over and read books. They left all the toys out, went outside, left that mess there, came back in, kept playing with it, and then they cleaned up before lunch. Are all programs going to do that? Probably not. However, it was less stressful. It doesn't have to be that extreme but think about minimizing those transitions a little bit. See if you can think outside the box and come up with some ideas.

Summary and Conclusion

To recap, the strategies we reviewed today are:

- Give transition warnings and individualized support to children who need it.

- Sing the directions, and not just at clean up time.

- Use play and children’s interests to engage and motivate.

- Choose your words carefully to avoid common mistakes.

- Use visuals that you already have, or be creative and make new ones.

- DON’T transition if you can avoid it because transitions are stressful.

If you have any questions, or if you try any of these strategies, I would welcome hearing from you. You can email me at barb@transformchallengingbehavior.com. I have a couple of blog posts on transitions on my website transformchallengingbehavior.com. In addition, I also have a cheat sheet you can use, that is downloadable pdf from my website. It includes some transition strategies for you, as well as some strategies for other times of the day.

Citation

O'Neill, B. (2018). Trouble with transitions: 5 essential ways to prevent challenging behavior. continued - Early Childhood Education, Article 22809. Retrieved from www.continued.com/early-childhood-education