Editor's note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Unlocking the Mystery of Selective Mutism, presented by Aimee Kotrba, PhD.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- List the key characteristics of selective mutism.

- Produce the avoidance cycle of selective mutism.

- Explain the two main intervention techniques to help children with selective mutism.

History of Selective Mutism

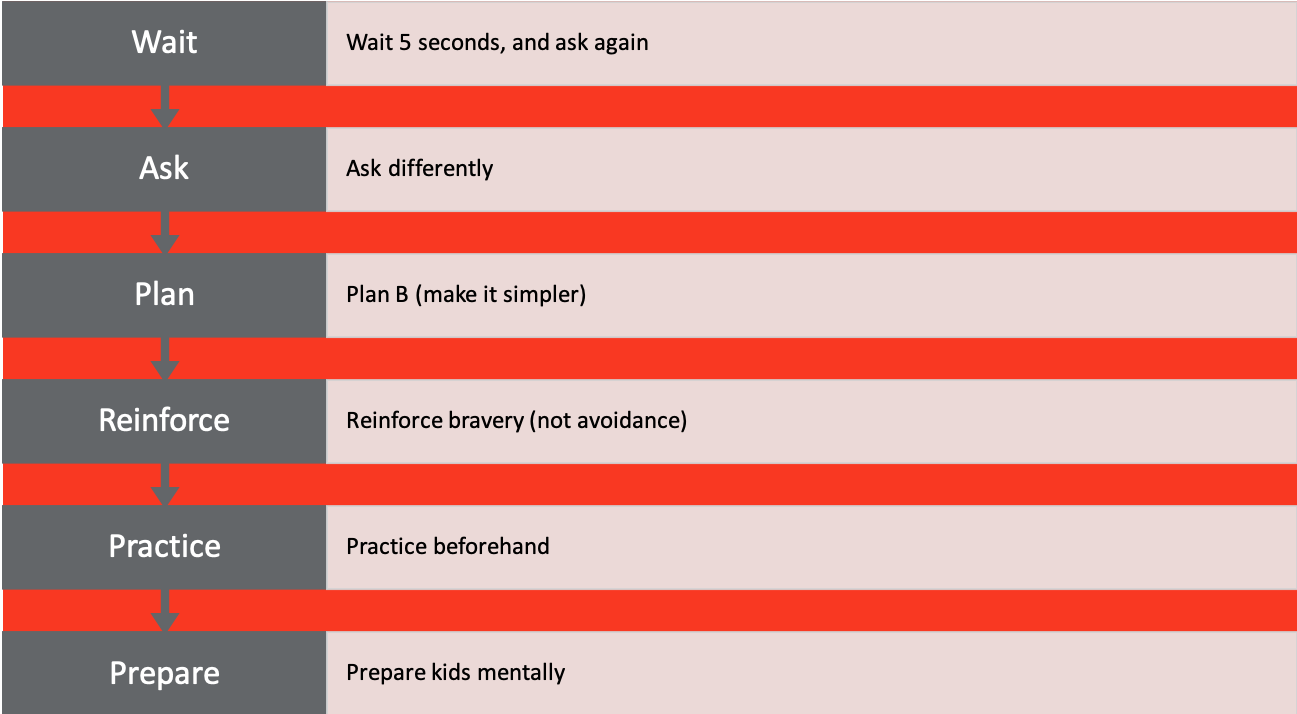

Figure 1. History of selective mutism.

I’m going to start by telling you a little bit about the history of selective mutism. It was first identified in 1877 at a boy's boarding school. There was a psychiatrist working there who noticed that a few of the boys at the boarding school were not speaking. He called their parents to find out more about what was going on, and the parents said they thought that was strange because they talked just fine at home. The physician got more interested in the phenomenon that was happening at the boarding school and he named the characteristics aphasia voluntaria. He had several thoughts about it. First, he believed that this was something that the child was choosing to do, to some degree. He believed that these children were choosing not to talk, and he thought that this choice not to talk was related to some sort of underlying trauma, or abuse, or neglect in their background history.

In 1934, it made it into the Diagnostic Statistical Manual (DSM) that psychologists used to diagnose. At that time, it was called elective mutism, still with this supposition that children were choosing not to speak, due to trauma, neglect, or abuse in their background. In 1994 our research finally caught up to us and a few changes were made, including renaming it selective mutism. This was due to the fact that these children speak in select environments, or to select people.

I think that it's somewhat confusing to people because I think people look at the name and think, oh, children are selecting not to speak. We actually don't believe that to be the case. We believe this to be an anxiety disorder, and that these children really can't speak, or that it’s very difficult for them to speak due to their overwhelming anxiety. We don't believe that they're choosing not to speak.

In 2015, when the DSM-5 came out, the newest edition of the DSM, they moved selective mutism to where it currently stands, which is within those anxiety disorders. It's there next to things such as social anxiety, specific phobias, and generalized anxiety disorder, with the assumption, based on research, that this is based in anxiety.

Definition of Selective Mutism

According to the DSM-5, selective mutism is a specific anxiety disorder. I think it's easiest to think about selective mutism as similar to a specific phobia, the same way that we have specific phobias of dogs, blood, heights, and flying. These children have a very specific fear of speaking. Sometimes it can be generalized even further than that, and it's a specific fear of communicating. For some of these children, it's not just talking, it's even things like gesturing, writing, or nodding and shaking their head. Even those ways of communication can be really anxiety provoking for them.

It's the consistent ongoing failure to speak in specific social situations, especially school. Most of the children that I see generally have a hard time speaking in all social situations including in school and in the community. This means they have a hard time talking to the doctor and the dentist, a hard time ordering at the restaurant, and a hard time speaking to their teacher at church school. They also tend to have a hard time talking to extended family members or family friends, particularly when they don't see those people very frequently. I think that school is a perfect storm for these children because there is a mix of performance anxiety, because children are being judged and graded, the social anxiety that goes along with interacting with peers, and being socially judged. For a lot of these children, their symptoms are first noticed at the beginning of their time in school. Preschool and kindergarten are often times the first moments of awareness that caregivers and parents have that something is different and something may be wrong. Perhaps being away from parents is a new experience so maybe there's even some separation anxiety mixed into it.

Selective mutism is not due to primary language disorder however, it is very co-occurrent with language disorders. It's very common that children who are diagnosed with selective mutism will have some sort of speech disfluency, or speech issue, that might include things such as articulation, tone, or being able to speak fluently (putting together sentences). About 50% to 70% of children who are diagnosed with selective mutism also have a language disorder. Other disorders like stuttering or autism, have been ruled out as the primary cause of not speaking. That doesn't mean that children can't have selective mutism and autism. It simply means that it can't be better explained by autism.

Selective mutism is relatively rare, affecting only about 1% of children in elementary school settings. There is some suggestion that prevalence is growing. I don't know if it's because we're getting better at identifying it or because it's like all other anxiety disorders in childhood, which all tend to be growing recently.

Finally, behavior is deliberate self-protection, not deliberate oppositionality. It can look quite oppositional, in fact, but we don't believe it to be driven by oppositionality. In other words, we don't think that these children are choosing not to speak or that they're doing it out of manipulation, defiance, oppositionality, or to get out of something they don't want to do. We really believe that it’s driven by anxiety and an overwhelming fear of speaking and being the center of attention.

Common Characteristics

- Mutism

- Blank facial expression, freezing, poor eye contact

- Difficulty responding and/or initiating nonverbally

- Slow to respond

- Heightened sensitivity

- Excessive worries

- Oppositional/bossy/inflexible behavior at home

- Intelligent

- Bilingual

Next, I’m going to talk about some common characteristics that go along with diagnoses of selective mutism. Mutism is, of course, a common characteristic, but it's important to know that it can happen on a continuum. There are children that I see in my clinic who have what I would call a severe presentation of selective mutism. This means that they talk at home, but outside of the home, they don't speak to anyone. They don't talk to their teachers, they don't order at restaurants, they don't talk to their cousins, and they don't answer grandma and grandpa when they talk to them. They basically just don't talk outside of the home. Then I have children all the way over on the mild end of this spectrum, where you wonder, is this shyness or social anxiety? They might be children who would answer in a very quiet voice if you directly ask them a question, as long as you're in a private location and they're familiar with you, but they often times don't respond to people in more public situations. They would never initiate conversation. They would never go up and talk to their teacher on their own accord and say, “Hi, how was your weekend?” or, “I need to go to the bathroom.”

These children tend to have blank facial expressions, freezing and poor eye contact, and difficulty responding and initiating even non-verbally. As I mentioned before, for some of these children, even communicating through gestures, writing, or drawing can be difficult for them. I think because of these three first characteristics, the most common misdiagnosis of selective mutism is autism. I would encourage people to be careful when they're considering a diagnosis of autism and find out from the parents how the child interacts in the home setting. If the child interacts in the home setting in a comfortable manner, speaks fairly freely, understands social nuances, and is interested in other children, you might be looking at selective mutism, as opposed to autism. Children with selective mutism tend to be slow to respond, so even when you ask them a question, if they answer you, there might be a really socially inappropriate lag between your question and their answer.

They tend to have heightened sensitivity and excessive worries. They tend to be predisposed to anxiety. Because of that, it's not uncommon that these children have other kinds of anxiety, not just selective mutism. They are often oppositional, bossy, and inflexible at home, so they look very different in the home setting. They tend to be intelligent if you can test them in a valid way, which can be hard.

There are much higher rates in the bilingual population. We're not entirely sure why this is, but we have a hypothesis that when children learn English as a second language, it's not uncommon that they enter what we call a silent period. That silent period is usually somewhere around three to six months, where they're learning the new language, taking it in, beginning to understand it, and maybe they can even write it. Speaking it tends to be the most challenging part of learning a new language, so they don't tend to speak the new language very much. We think that bilingual children with selective mutism may enter this silent period. We also think that they may have some underlying predisposition or tendency towards anxiety, so when they go into this silent period and they're already anxious about speaking in general, they never come out of it. It becomes a part of their behavioral repertoire, something that just becomes a habit for them in a sense. What's really interesting is that for a lot of children, once they become selectively mute in a second language, even if you spoke to them in their primary language, the one that they're very comfortable with, they still won't answer you.

How Does Selective Mutism Originate?

How does selective mutism originate? I think this is a really interesting question and one that I don't think is adequately discussed in the general public. For a lot of people, when you bring up this idea of selective mutism, they give you the old-fashioned response, which is, oh, that's because they had some sort of terrible trauma or neglect in their background history, that's why the children don't talk. Sometimes this is even supported by Lifetime movies that have a child whose parents die in a fiery car crash and then he stops talking. Then eventually, over time, he's healed and he starts talking again. That's not selective mutism.

With children with selective mutism, you're talking about children who have no evidence of a causal relationship to abuse, neglect, or trauma. These are children who have no history or no evidence of a causal relationship. This means it's one thing to say that the selective mutism came about because of abuse, neglect, or trauma, but it's a whole other thing to say that maybe they had that in their background history, but we can't find any reason why those two things are connected. The latter statement is more accurate. In fact, we see a lot of children whose parents are great parents.

We know that these children tend to have what we call a genetic predisposition model. These are children who have a genetic loading towards anxiety, meaning anxiety runs in their family. Now, these little children have a genetic loading because mom, dad, or extended family members have anxiety.

There are also biological indicators seen in what we call a decreased threshold of excitability in the amygdala. The amygdala is the part of our brain that gives us the fight, flight, or freeze response and tells us if we're in danger. A decreased threshold of excitability is a fancy way of saying that the amygdala gets excited too easily and gives them the warning signal too easily. Even in very young children, we see that their amygdala gives them the warning signal much too easily and much too quickly and then it takes a lot longer to return to normal.

We had young children receiving the diagnosis of selective mutism. This was due to a genetic predisposition (mom and dad probably have some sort of anxiety that runs in the family), a biological indicator (their amygdala is overreactive and gives them the warning signal way too often, usually happening from birth), and some modeling from the child’s mom and dad. Even children at a young age will observe mom and dad reacting with anxiety in situations and will model that behavior. When all of those are put together, it becomes a difficult and challenging mix of characteristics that we think could lead to selective mutism.

Prevalence Characteristics

Most stats show that the prevalence of this is about 1% in elementary school settings and growing. When I say 1% in elementary school settings, we actually believe that selective mutism begins really early in development. I don't mean that these children are suddenly showing characteristics when they're in elementary school. For most of these children, parents will look back and say, “They were like this for as long as I can remember. As early as I can remember, they shied away from talking to new people and they had difficulty talking to extended family members. They didn't talk to their preschool teachers. They didn't talk very much and didn't interact with children in our library group.” It's often times only in late preschool or early elementary school that children are finally identified as having selective mutism because we don't expect that much speaking from a two-year-old or a three-year-old, especially in social situations. We don't necessarily expect a three-year-old to order at a restaurant or to answer their doctor's questions. We would expect that of a five, six, or seven-year-old, so that's the point at which these children often get officially diagnosed. For these children, the symptoms and signs show up very early, and in fact, children can be diagnosed with selective mutism as early as age two to three years.

In order to get a diagnosis of selective mutism, the child must be one who does not easily speak or does not speak in a school like setting, for at least six months. These children have been in a school like setting, such as a preschool or consistent daycare setting, for at least six months, and they're not speaking or not speaking very much. Considerably different from their peers perhaps.

Garcia, Freeman, Francis, Miller, and Leonard (2004) found that 1.5 to 2.6 females are diagnosed in relation to every male that's diagnosed, so a lot more girls are diagnosed with selective mutism in comparison to boys. There are hypotheses about why we think this might be. One is that it’s actually more common in girls than it is in boys because we know that girls at any age are more likely to be diagnosed with anxiety than boys. Boys are much more likely to be diagnosed with things like oppositionality and autism, whereas girls are more likely to be diagnosed with anxiety and depression. Another possibility is that maybe we don't notice it as much in boys because we have an expectation that girls are going to talk a lot more than boys, especially at young ages. Think of the way in which girls play with each other. From a young age, there's a lot of verbal engagement. They're playing dolls, house, kitchen, and restaurant and there's speech that goes along with all of that play and interaction. On the other hand, with young boys, you see things more like rough and tumble play, sports play, playing chase, and jumping on things. There's a lot less need or expectation for speech in those interactions. Perhaps it happens just as much in boys, but we just don't notice it, because it's not as obvious when a little boy doesn't talk as when a little girl doesn't talk.

Coexisting Problems

- Social Phobia

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder

- Other Specific Phobias

- Obsessive Compulsive Characteristics

- Speech Problems (35-75%)

- Defiance/Oppositionality

- Enuresis

- Sensory Dysfunction

- Separation Anxiety

- Hearing Issues

There are a lot of coexisting issues that could go along with selective mutism. The most common one is social phobia, but any of the anxiety disorders are common coexisting problems with selective mutism. Social phobia differs from selective mutism in that selective mutism is a very specific fear of speaking or communicating. Social phobia is the fear of being the center of attention or fear of people looking at you. A lot of these children have both of those fears and could be diagnosed with both.

Most children who have selective mutism can be diagnosed with another kind of anxiety disorder as well, such as generalized anxiety or other kinds of specific fears or phobias. A lot of these children will have obsessive compulsive characteristics such as rigidity. As I noted before, there are a lot of speech problems in this population. Depending on what kind of research you're looking at, anywhere from 35% to 75% of children with selective mutism will also be diagnosed with speech and language issues. Defiance and oppositionality is often seen in the home setting. A lot of parents will say, “This is my most difficult child, she is defiant, oppositional, bossy, and inflexible at home.”

Enuresis, or daytime wetting, is really common in this population. This might be because children have a difficult time indicating to the teacher that they need to go to the bathroom. As children get older, there are less frequent prompts for them to go to the bathroom. Children in daycare or in preschool might be frequently prompted to use the bathroom and as they get older, there are less prompts. Sometimes children need to go to the bathroom outside of those prompts and if you don't speak to the teacher or speak very much at all, it might be really hard to go up and ask to go to the bathroom. This leads to a wetting accident.

There is a lot of sensory dysfunction that occurs in this population, such as difficulty with textures or sounds. Separation anxiety is very frequent in this population, so you may see difficulty parting from parents or caregivers. Part of that might be that they are fearful of being away from someone who can talk for them.

Interestingly enough, we do find some research that suggests that about 50% of children with selective mutism have hearing issues. I'm not an audiologist, so this is my general understanding as a non-audiologist. The way that our hearing system works is that when I'm speaking I can understand what other people are saying as they speak. Even if I'm talking and someone else is talking at the same time, I can process what they're saying. This is auditory processing skills. We think that children with selective mutism may have difficulty processing what other people are saying when they themselves are talking. If you have a child who is already predisposed to anxiety, they don't want to miss anything, whether it’s the teacher giving them a direction or children coming and talking to them on the playground, so instead, they end up staying quiet so that they don't miss some sort of interaction that's going on around them.

Selective Mutism Subtypes

- Anxious

- Anxious/Opposition

- Anxious/Communication Delayed

There's some suggestion that there are some subtypes to selective mutism. One is what I would call the just anxious children. They are like the deer in the headlights children, the ones who when they're prompted to talk or when they need to speak to an adult they get tearful, back away, hide, and avoid. There are anxious oppositional children who, when spoken to, instead of getting tearful, might look defiant or angry in their non-speaking behavior. Then there are children who are anxious and communication delayed. These are children who have anxiety, but also have that speech and language delay, which may make it more difficult for them to talk.

Conceptualizing Selective Mutism

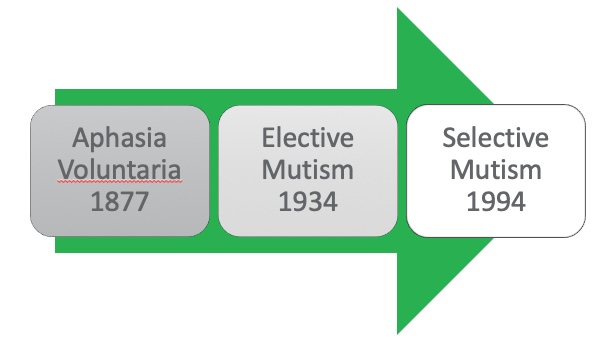

Figure 2. Conceptualization of selective mutism

That leads us to this conceptualization of selective mutism. Think about what is it, where does it come from, and how is it maintained by people. There are young children who are coming into this conceptualization with a genetic predisposition for anxiety, their parents may be modeling some anxiety for them, and their amygdala is giving them the fight, flight or freeze response. They are put into situations where they are prompted to speak or engage. This may happen hundreds of times per day, even for very young children, where somebody talks to them or asks them to speak.

An example of this happening in preschool might be during choral responding at the carpet. This would happen when the child is asked a question by an adult or when the child is approached by other peers. It would happen when the child needs to go to the bathroom and needs to ask to do so. It might happen with expectations of the child using polite words like please and thank you at snack time. It happens at home and in public when adults and other children prompt these children to speak, answer, or engage verbally. When that occurs these children with all of these predisposing factors get too anxious and they avoid. This is not pathological, per se, this is what we all do. Think of a time where you felt really anxious and uncomfortable about something. I can almost guarantee that your very first response was, how do I get myself out of this? How do I avoid this, how do I not do this?

These children with selective mutism get anxious and they try to avoid that speaking interaction. Then somebody steps in and rescues them. I put adult rescues, but peers, siblings, parents, and teachers are all very frequent rescuers as well. They do it in a lot of different ways. The most common way is they talk to the child. For example, the child comes into their daycare and the daycare teacher says, “Hey Jenny, what did you do this weekend?” Jenny looks fearful and looks at her mom and her mom says, “Oh, we had a really great weekend. We went camping this weekend.” Jenny's mom has now taken over the conversation for Jenny and has rescued her. Another way that adults rescue is by no longer asking the child a question. When it comes to their turn at carpet time, the teacher skips right over them, doesn't ask them any questions, or doesn't prompt them to answer questions out loud. We'll start asking them only yes/no questions so that they can nod or shake their head or we'll only ask them to do things like point to things to respond. Peers can be rescuers by talking for the child. I've seen children as young as three years old very specifically say to a substitute teacher or daycare providers, “Jenny doesn't talk.” Peers step in and rescue in that way.

When somebody rescues, it decreases anxiety. It decreases anxiety for the child, because now they no longer have to do what they were feeling fearful of doing, and it decreases anxiety for the adult because nobody likes to watch a kid struggle. That's what it often times looks like. The child gets that deer in the headlights look and so we rescue. When we rescue, the child looks more comfortable, it decreases our anxiety and discomfort, and that accidentally reinforces that behavior.

Next time, the child is more likely to avoid and the adults or peers are more likely to rescue them by stepping in quickly, answering for them, stop asking them questions, or letting other people know not to ask them questions. The problem is that this gets practiced time after time, day after day, month after month, year after year, over and over again, until this becomes the child's way of interacting with the world. That's really the crux and the difficulty of dealing with selective mutism is that these children get a lot of practice not talking and we get a lot of practice rescuing them.

Evidence-Based Intervention for Teachers and Caregivers

Given that we tend to be rescuers and these children tend to find successful ways of avoiding, let's start talking a little bit about what caregivers and teachers can do to help.

First Things First - Warm Up and Develop Rapport

The first and arguably most important thing in working with these children in any capacity is developing a rapport or a good, comfortable relationship with them. Often times, children with selective mutism need warm-up time, on a daily basis. I regularly recommend that even when children are capable of answering questions in the preschool or daycare setting, adults give them a little bit of warm-up time at the beginning of the day instead of expecting them to start answering questions the second that they walk into class.

One of the best ways to help build a relationship or develop a rapport with an adult is through something that we call PRIDE skills play. This is a positive way of interacting with a child that shows empathy, warmth, and positive regard in kind of a systematic way, something that you have a skill set for.

During this rapport building time or relationship building time, the adult and the child play a game or do an activity, play with the dolls, or pretend play. It should be something the child finds interesting. During this time, the adult does not prompt for speech, does not ask questions, does not give commands, and isn't trying to teach the child. The adult’s main goal is just to help the child be comfortable and have fun with the child. During this time, the adult’s jobs stand for this PRIDE acronym.

- PRIDE skills play

- P = labeled praise

- R = reflection

- I = imitation

- D = behavioral description

- E = excitement/enjoyment

- NO asking questions, giving commands, or teaching!!!

The P is for labeled praise. The adult is giving a lot of labeled praise of what the child is doing appropriately. Let's say that you're building with Legos with a child. You might say something like, “Oh, I love the way that you're using so many different colors. Your house is really coming together nicely. That looks fantastic.”

The R stands for reflection. Anytime the child is communicating something to you in any way the adult is reflecting it back or saying it back. Now some children, when they feel comfortable, will answer some of your questions or will talk to you a little bit. If the child does say something to you, you reflect it back. It sounds just like this:

Adult: “I love the castle you're building.”

Child: “It's a house.”

Adult: “It's a house, thanks so much for letting me know.”

Reflecting is just back exactly what they said. More commonly, with a child with selective mutism, they're not talking to you. You might be reflecting things that they're communicating to you non-verbally, through gestures, or through pointing. If the adult and the child are building with Legos an interaction with reflection of non-verbal gestures/pointing might look like this:

Adult: “I love your castle that you're building.”

Child: Points to the moat that they're putting around the castle.

Adult: “Oh, thank you for showing me the water that you're putting there. I love that. What a good idea.”

The adult is reflecting back what's being communicated, even though it’s non-verbally.

The I stands for imitation. Imitation means that the adult is doing what the child is doing. They're playing with the child, not just standing over to the side watching the child.

The D stands for behavioral description. This is best thought of as a play by play. The adult is giving a play by play of what's happening in the play interaction, like a play by play announcer at a baseball game. They're saying things like, “I love the blocks that you're choosing to use. Those are beautiful colors. Your castle is really coming together nicely. Oh, and now you're building another side to it. You're making it so tall right now.” You're basically just providing the commentary.

The E stands for excitement and enjoyment. Obviously, you want to show that you're enjoying your time with this child.

The reason that during this time we're not asking questions is that this is a time for the child to get comfortable with us and to warm up as well. We don't ask questions specifically during this time because we don't want to break that development of comfort that's happening. After a child gets warmed up and has developed a rapport with an adult, then they can start asking questions. We're going to talk about the manner in which we can successfully do that.

Slowly Facing Fears…Desensitization

The overarching idea of helping children with selective mutism is this psychological term that we call desensitization, which means slowly facing fears at a reasonable pace. It's similar to the way that you would interact with a child who was afraid of dogs. If you had a small child that was afraid of dogs, maybe at first you would start playing with them with stuffed animals and watching cartoons with dogs in them. Then you might go to the pet store but stay pretty far away from where the dogs are kept. You would then get closer to where the dogs are kept and keep going up to where the dogs are kept, then maybe even petting one.

It's a slow, steady facing of fears at a pace that the child is able to do. We do the exact same thing with selective mutism. We encourage them to do things that are slightly outside of their comfort zone. We start with the easy ways of responding and then we get a little more complex as we go along.

Given the fact that I only have an hour to talk to you about selective mutism and the fact that the intervention can be more complex than this, I'm going to touch on and give you some ideas of things that could be helpful and useful for children with selective mutism. If you have an interest in this and you want to find out more I would encourage you to consider looking at my book, Selective Mutism: An Assessment and Intervention Guide for Therapists, Educators, & Parents. It gives a lot more information on all of these intervention techniques.

Two Types of Desensitization

- Stimulus fading

- Shaping (communication ladder)

There are two main types of desensitization or facing fears. One is called stimulus fading. That is the easiest, most naturalistic, quickest option you have available to you. The other option is called shaping and we'll talk about the different times when you can use these techniques.

Stimulus Fading

Stimulus fading is gradually increasing the number of different people the child speaks to and settings the child speaks in, by gradually introducing new people into conversations. What happens all too frequently is that the child is talking to her mom out in the hallway of the daycare or the preschool, the preschool teacher walks up to the pair and immediately asks a question, and the child shuts down.

The idea of stimulus fading is that instead of being that abrupt, we're going to fade, or slowly introduce, a new person into the interaction. When I say new person, I don't necessarily mean new to the child, but I do mean somebody that they don't talk to right now.

I'll give you an example of how this would look in a preschool setting. Perhaps Mom and teacher are able to stay after class, come in before preschool starts, or maybe come in on an off day of preschool. You want a time when it's relatively private, there's not going to be a lot of other children running around, and an audience listening to what's happening. The child and Mom start off in a room by themselves and Mom's job is to keep the child talking. Often times, we do that by playing games, engaging the child in activities, or talking about topics the child is particularly interested in. With little children, it's fun to do things like naming games or pretend play such as playing restaurant, kitchen, or school. The parent’s job is to try and keep the child talking.

At the same time, the preschool teacher is starting outside of the room and she's very slowly entering into the room. At first, that means she enters the room, but she goes to the back where her desk is and she's doing some paperwork or working on her computer. She's doing something so she's not paying attention to the child and to Mom. As long as the child continues talking, the preschool teacher can get a little bit closer. This may be two, three, or four minutes later, but the teacher gets up and walks a little bit closer, all under the guise of, I'm not paying attention to you, nor am I interested in what you're doing over there. As the teacher is moving closer to Mom and the child it's a great time for her to clean, reorganize desks, or cut material that is needed for the next day. The teacher is doing something and keeping busy. As long as the child continues talking to Mom, the teacher can then approach the table that they're sitting at or the area that they're sitting in.

The teacher doesn't engage the child in speech yet and doesn't ask any questions, but just gets closer and starts paying attention to what's happening. The teacher may start looking at the child and the parent or may start laughing along with funny things that are said. The teacher could start commenting on what Mom and child are saying. For instance, if the child says, “Mom, it's your turn to order,” the teacher could say, “Oh, that's so nice of you to give Mom a chance to order.” The teacher is basically reflecting back what the child was saying. Again, as long as the child is able to maintain speech then the teacher can start asking a few questions.

As we're going to talk about in just a minute, the most effective kind of question is something that we call a forced-choice question. This could also be called a multiple-choice question. You're providing the child with the answer options. For instance, the teacher says, “Who's going to be the waitress this time, you or Mom?” That's a forced-choice question. Or the teacher could say, “Oh man, this looks delicious. Is this dessert a cookie or a donut?” The teacher asks some forced-choice questions and frequently if a teacher has slowly faded themselves into the interaction, most children will actually respond to that, even if they look at Mom. Sometimes the child will look at Mom and respond, but as long as the child starts responding to the teacher, then the parent can start fading themselves out of the interaction. The parent will do that by first getting busy with her own stuff. Maybe Mom suddenly needs to check her emails on her phone and then she needs to walk to the other side of the classroom to get something out of her purse. Then maybe Mom needs to go to the bathroom and she walks out of the classroom. Now the child is speaking directly to the teacher instead of to Mom, so we transitioned speech from Mom to teacher.

Most people are actually very surprised by how well stimulus fading works. One caveat I would say is that for most children, the first time that they do this it takes a little bit of time. There has to be some slow movement involved. It might take the teacher or the daycare provider 30 minutes to even an hour to get through all of those steps. What we often see is that after you've done stimulus fading once or twice, the child gets much more efficient at it. This means that as you do the stimulus fading for the co-teacher, the other daycare worker, and maybe a new friend or a peer in the classroom it gets a little bit faster and a little bit easier.

Types of Questions

- Yes/No

- Forced-Choice

- Open-Ended

- Stay Away From

- Complex questions

- Really open-ended questions

- Feelings questions

Forced-Choice Questions

There are different types of questions that adults are encouraged to ask during these stimulus fading interactions with children or in general with children with selective mutism. The most effective type of question to pose to a child with selective mutism is a forced-choice question. There are a few reasons why we think that might be effective. One is that it says to a child, I expect you to give me a verbal answer. It's very difficult to respond non-verbally or with gestures to a forced-choice question. If the daycare provider says, “Do you want a cookie or a piece of chocolate for lunch?” it's very difficult for a child to use a gesture to respond to that. It necessitates speech. The other reason that we think forced-choice questions are effective is they give the child options and tell the child these are the right possible answers that you can give. The child doesn't have to do any processing and it takes away a lot of the language demand and the cognitive effort. Forced-choice questions are by far the most effective type of question to use with children with selective mutism.

Open-Ended Questions

Open-ended questions can also be good, but they do necessitate some language processing. If you say things such as, “What's your favorite color?” the child has to think about what colors there are, how to say them, and what's their favorite. The child also may be thinking about what the daycare provider wants to hear is their favorite and what people might think about their favorite. They have all of these thoughts going through their head that might slow down their response.

Yes/No Questions

Yes/no questions aren't the preferable type of question for a child with selective mutism, specifically because they allow for a nod or a shake of the head. They don't ask the child to face their fear of speaking. If you ask a child with selective mutism a yes/no question, the child will probably nod or shake her head. We generally try to stay away from yes/no questions and we focus more on forced-choice and then secondarily, open-ended questions.

Stay Away From…

Things you definitely want to stay away from are complex questions. You don't want to confuse a child with your question. You want to make your questions really easy for them to answer, especially for children with selective mutism. Ask concrete kinds of questions about things that they would automatically know, such as colors, simple counting, or the names of things. Those would be pretty concrete questions to ask a child with selective mutism.

You don't want to ask really open-ended questions. An example of a really open-ended question would be something such as, “Jeremy, what did you do last summer?” That's a really open-ended question where the child has to do a lot of processing to come up with an answer. Instead, you might want to make those questions forced choice. Some examples of making a really open-ended question into a forced-choice question include:

- Did you go on a trip or stay at home last summer?

- Did you ride your bike or not ride your bike last summer?

- Did you play with friends, go to the pool, or something different last summer?

Things like feelings questions are hard for children to answer at any point, but particularly for young children with selective mutism. When you ask them questions such as, “How did you feel about that?” or “What do think about that?” you’re asking a really complex question. We typically stay away from those.

Shaping

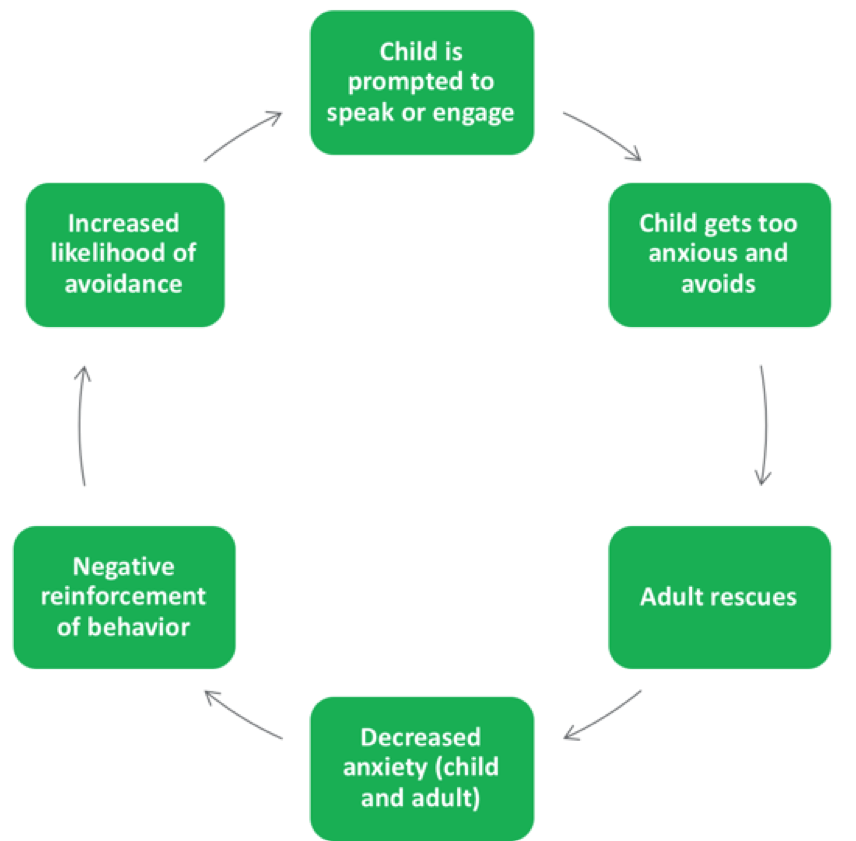

Figure 3. Flow chart on forced-choice questions.

Figure 3 shows a flow chart on the way in which an adult could successfully prompt a child who has selective mutism for speech. The adult is to ask a forced-choice question because we know that tends to be the most effective. If the child gives a verbal response, then the adult gives labeled praise. Here’s an example:

Adult: Will, do you have a dog or a cat at home?

Child: Dog

Adult: A dog. I love dogs. Thanks for letting me know.

If the teacher gives a forced-choice question and gets no response, the first thing the teacher does is wait a very long and socially inappropriate five seconds and then repeat the question. In the previous example, the teacher says, “Will, do you have a dog or a cat at home?” If the child doesn't respond and has a deer in headlights look the teacher waits five seconds and then repeats the question. “What do think buddy? Do you have a dog or a cat at home?” If the teacher still doesn't get a response then jump down to that reduce expectations in the bottom right-hand corner. We'll get to that in just a minute.

If the child gives a non-verbal response, the teacher can either just wait five seconds or probe for a verbal response. Using the previous example, the teacher might say, “Will, do you have a dog or a cat at home?” Maybe there’s a dog poster hanging in the classroom and Will points to the dog in the dog poster. The teacher can do two things. She can just wait five seconds, which can be uncomfortable for the child, and he might respond verbally. She can also probe for the verbal by saying, “I see you pointing, but I'm not sure what you're pointing at. Do you have a dog or a cat at home?” If the child gives a verbal response at that point and says, “Dog” the teacher could then say, “A dog. I love dogs. Thanks for telling me.”

If the child gives no response or still goes with that non-verbal gesture of pointing at the dog, the teacher waits five seconds and reduces expectations. This means the teacher makes it easier to answer in some way. There are different ways that you can make it easier for a child with selective mutism to respond. One way is allowing them to nod, shake their head, or point, but, if you don't have to I would prefer to stay away from that one. You could make giving a response easier. This can be done by saying, “If you have a dog at home, you could say, duh, for dog, and if you have a cat at home, you could say, kah, for cat.” You could go to someplace more private because perhaps there are a bunch of other children all sitting around and listening and the child is nervous about these audience members. You could ask the child to respond non-verbally perhaps, but you want to try to get a response out of them by making it a little bit easier for them.

Only Change One Factor at a Time

- Audience

- Location/environment

- Speech demand

Another thing that I always recommend that adults be aware of is only changing one factor at a time. Changing too many, especially at first, increases anxiety and is likely to lead to regression. These three are sort of like pitfalls, ways that we accidentally make speaking more challenging for a child without actually intending to make it challenging.

The things that you always need to consider are who is the audience, what kind of environment are we in, and what kind of speech demand am I asking of the child? You only want to change one of those at a time. For instance, if the child does the stimulus fading procedure with a preschool teacher and now they're answering the preschool teacher in the classroom that doesn't necessarily mean when they go out at recess and all the other children are there that they'll still answer the teacher. Instead, what you have to do is go outside to the new environment and practice just talking to the teacher. Another option is to practice adding audience members in the classroom setting so the child is talking to the teacher in the classroom privately, but you could add in a few audience members or a few additional children.

You also want to be careful not to increase the speech demand too much. Sometimes I see parents do a stimulus fading with a daycare provider and the child begins talking to the daycare provider in a private setting and is answering forced-choice questions from the daycare provider. Then the parent might say, “Will, tomorrow I want you to go in and say, ‘Hi, how was your weekend?’ to the daycare provider.” That's really increasing the speech demand for the child because now the child is going from responding to a forced-choice question, which is pretty easy, to initiating in a sentence to the teacher, which is much harder.

We have to be careful of the factors that we're changing and we only want to change one at a time, then just simply be aware of them.

Speech Shaping

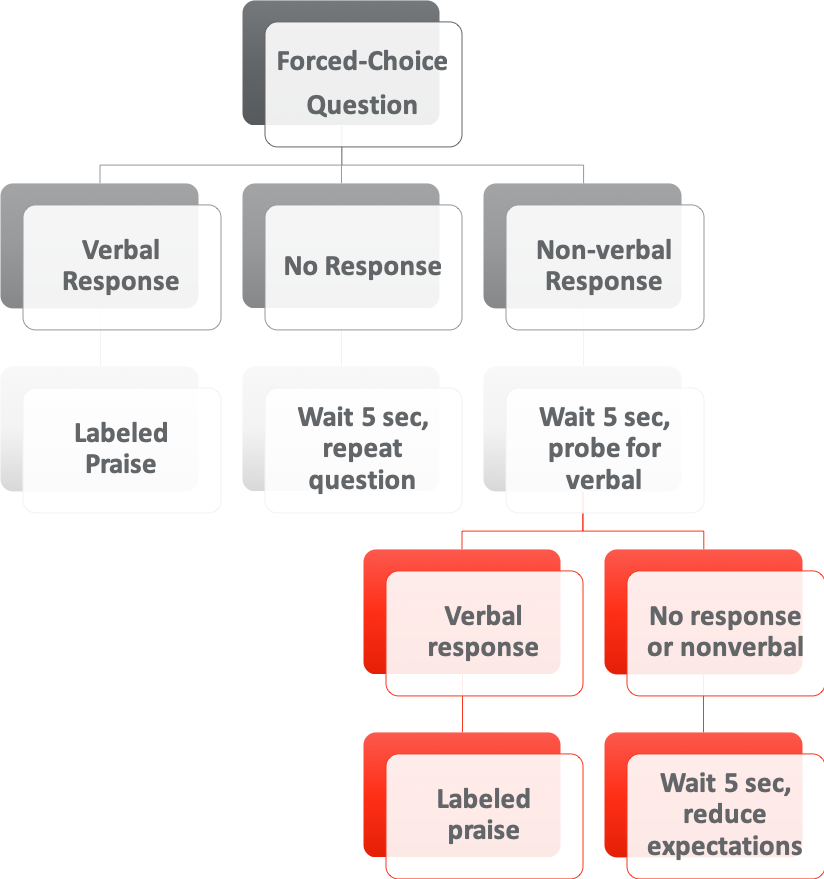

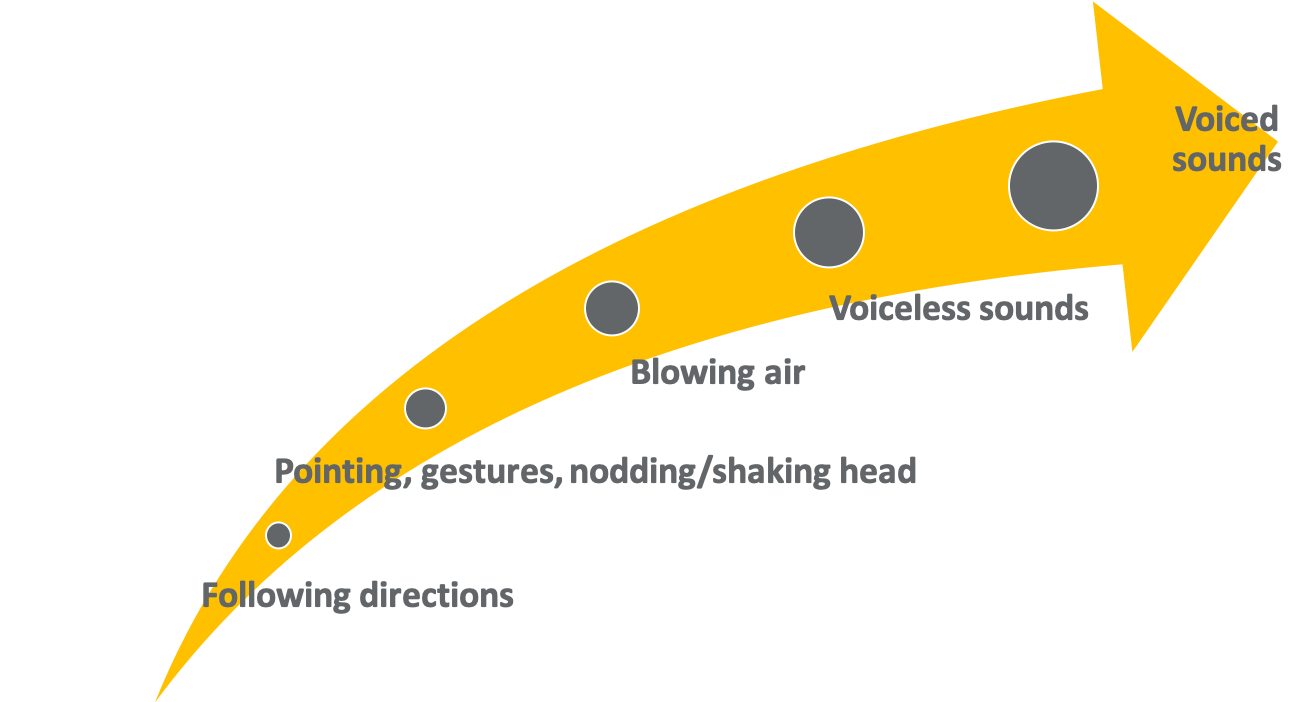

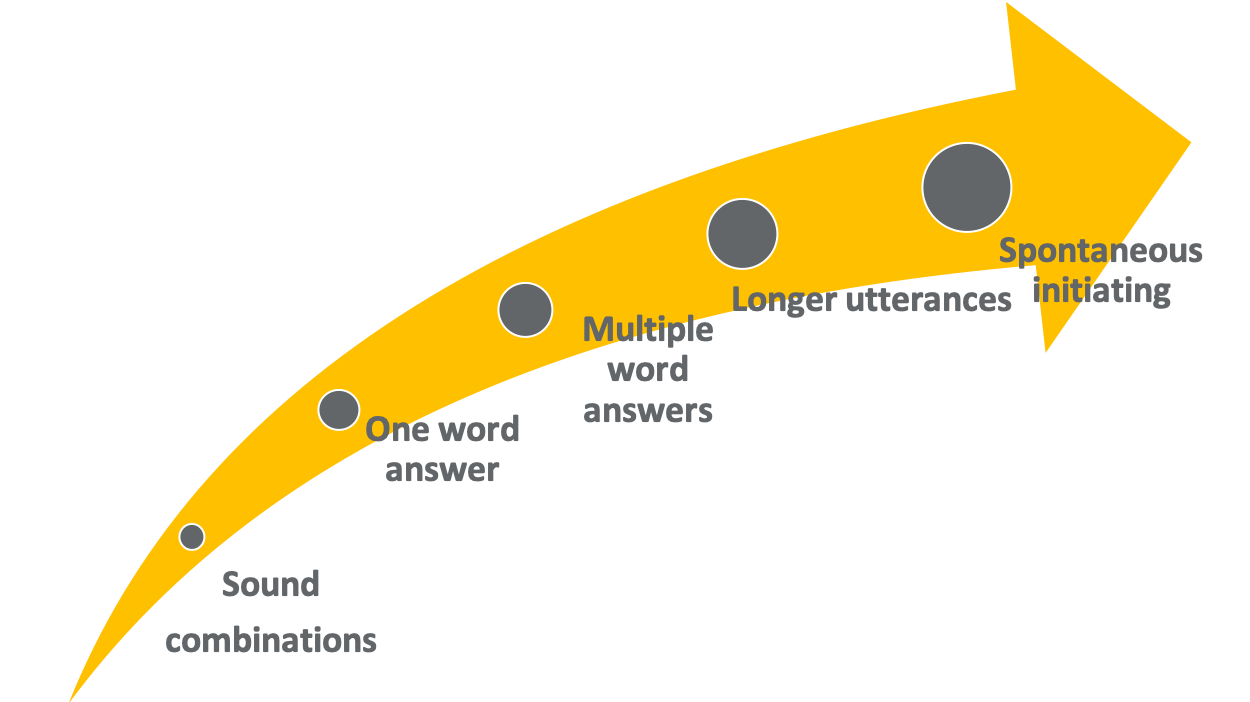

Figure 4. Speech shaping.

If stimulus fading and forced choice-questions don’t work, another option that you can use is shaping. You would shape this behavior in the same way you would shape any behavior, which is by reinforcing successive approximations of the behavior. If you're trying to teach a child to tie their shoe, at first, you're just teaching them to cross the shoelaces. You would practice that over and over again, then teach them how to do the tuck under and practice that over and over again as well. Then you make the two bows and you practice that over and over again, then cross the bows. There's a systematic way in which you shape children tying their shoelace.

We do the same thing with children with selective mutism. We can practice what we call speech approximations with children in a slow, steady way if they're not able to do stimulus fading. For instance, we could do things such as practice blowing air, practice making voiceless sounds (like whispered sounds), then practice voiced sounds, then combine those sounds into one-word answers then multi-word answers.

We can practice these in many fun, engaging ways. For example, if you were practicing blowing air with a child you might do things like blowing up balloons, blowing bubbles, or blowing cotton balls and having cotton ball races. Then when you're practicing sounds you might ask a child to make the sounds of cars or the sounds of tea kettles or some other similar sound.

You can practice these small steps towards speech if you need to, but my warning is that this tends to take longer than stimulus fading. If you can engage a child in speech through the stimulus fading procedure that we talked about, I always recommend people try that first.

If a Child Doesn’t Answer

Figure 5. What to do if a child doesn’t answer.

What do you do if the child doesn't answer? It's always everyone's question. The first thing that you do is you always wait five seconds and ask again. Always. A lot of these children have learned that avoiding the first question means that within two seconds the adult has moved on, or answered the question for them, or gone on to the next thing. They're really good at avoiding answering.

Wait

If you just wait five seconds in silence, it's socially uncomfortable, but it says to the child, I'm really here and I'm going to wait for your answer. Ask again. Asking the same question over again says to the child, I mean it, I really want to get an answer from you.

Ask

You might have to ask differently. Sometimes I've made the mistake in forced-choice questions of not giving the right answer. I've said something like, “Do you have a dog or a cat at home?” If the child has both a dog and a cat at home, they're not going to correct me and say, “Well actually, I have a dog and a cat at home.” That would make them very anxious. So sometimes I have to ask differently. Instead, I could say, “Do you have a dog, a cat, or both?”

Plan

You can do what we call plan B, which is to just make it easier. Make it simpler, take them someplace private, have them just make the first sound of the word, shorten the response that they need, or change it to a forced-choice question. Any of those options would make it simpler.

Reinforce

You want to reinforce bravery, not avoidance. Give them labeled praise when they do respond. You don't want to make a big deal out of it and throw a talking party, but you do want to say something like, “Thanks for letting me know,” or “I love your answers,” or “That's really helpful when you tell me that.” They should be matter of fact praises that will reinforce speaking.

Practice

Practicing beforehand. If you're going to do something that's kind of challenging then maybe you need to practice that a few times, before the actual real deal. For instance, if the child is going to answer a question on the rug during group time, maybe the child and the teacher sit on a rug by themselves a few times and practice it before the child has to answer in front of their peers.

Prepare

Preparing children mentally for what to expect is very important as well.

Contingency Management (AKA Reinforcement)

- Child avoids talking = reduction of anxiety = negative reinforcement

- Child is more likely to avoid speaking

- Goal – making nonverbal communication less reinforcing and verbal communication more reinforcing

- No longer accepting nonverbal gestures as a response

- Not answering for the child

- Stop avoiding asking the child questions

- Providing positive reinforcement following verbalizations (e.g., praise, stickers, points, toys)

This section on contingency management is a very complex way of saying we want to focus on rewarding speech and bravery, as opposed to what we have historically been doing, which is reinforcing avoidance and not talking. We want to make talking more rewarding and not talking less rewarding. We can do this by doing things such as being careful not to answer for the child, stop avoiding asking the child questions, and then providing positive reinforcement following verbalizations. Many children are very responsive to positive reinforcement.

I had a little girl who was in a preschool class and she loved jewelry. The teacher made her a really cute necklace with Velcro spots on it. Every time that she answered a question she got to put a little jewel on one of the Velcro spots. By the end of the day if she'd answered all of the teacher’s questions she had this really cute jeweled necklace that showed how brave she had been that day.

Tips for Encouraging Speech

- REMAIN CALM!!!

- Use specific praise

- Judicious use of direct prompts to speak

- Brave talking is target behavior, not correctness

- Always wait 5 seconds for a reply – child needs an opportunity to respond

- Try to always ask forced-choice or open-ended questions instead of yes/no questions (to avoid head-shaking)

- Use situations that are motivationally driven to encourage more speech

- Don’t mind read

Here are some tips for encouraging speech. Remain calm yourself. It is really anxiety provoking for adults as well as the child and uncomfortable to push a child a little outside of their comfort zone. But remain calm.

Use specific praise for the child. Don't be afraid to prompt them to speak. I don't correct children even if they say something wrong. If I said, “Do you have a brother or sister at home?” and they said, “I have a sister” and I know that they don't have a sister, I probably wouldn't call them out on it. Instead, I would probably say, “Oh, thanks for letting me know.”

Always wait five seconds. Try to use forced-choice questions. Be careful not to mind read. Children with selective mutism tend to be excellent at being little mimes. They act in a certain way or direct their eyes in a certain way, or gesture in a certain way to let us know what they mean. Once we're working on speaking more, I become very stupid. I don't know what they want unless they use verbalizations with me.

Specific School Interventions

- Desensitization in school with key worker

- 5-10 minutes of practice daily or 15 minutes 3x/wk

- As structured as possible

- Team meetings and communication

- Chores that involve speech

- Extracurriculars

- Seating arrangement/small group activities

- Conversational partners/conversational visits

- At-school practices during summer

- Meet with teacher prior to new school year

- Anticipating problems/obstacles/changes

- Discuss anxiety-provoking transitions in advance

Some specific school interventions that can be used even at the preschool setting include desensitization in school with the key worker. In elementary school, I call the interventionist a key worker, but in preschools or daycare settings this would be practicing speaking with the daycare provider or the preschool teacher.

Other interventions include doing chores that involve speech. This may be going to the preschool office and handing the secretary there an envelope and saying, “This needs to be sent to Mrs. Smith.” You also want to encourage children to be involved in extracurriculars. Seat them next to children that they already talk to.

Let them have practices at school during the summer or at daycare when they're not there over the break. It’s important to keep preschool, school, or daycare as a place where they talk. Allow Mom to come into the preschool during the summer months and just walk around and talk with the child. This helps solidify to the child that this is a place where I speak. Meet with a new teacher or a new daycare worker prior to the new school year.

Discuss transitions, problems, obstacles, or changes with the child before they happen. That might include a substitute daycare provider coming in, an anxiety-provoking fire drill, or something like that.

The last two references in the references section below are great overviews of intervention research that are relatively new.

Question and Answer

Moderator: How often do you typically see selective mutism in early childhood, in children under five or below kindergarten?

Dr. Kotrba: We see at the same prevalence rates as we do in an elementary school setting, so about 1% of the population. A lot of preschools and daycare settings will reach out to us seeing that they have some of the symptoms that are developing and wanting to nip it in the bud, so to speak, before it becomes full-blown severe selective mutism. Children being in a daycare or preschool is an excellent time for them to get intervention if providers or teachers even think that their children are heading in this direction. It's a great time to be able to practice speaking with the child.

References

Garcia, A., Freeman, J., Francis, G., Miller, L., & Leonard, H. (2004). Selective mutism. In T. Ollendick & J. March (Eds.), Phobic and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: A clinician's guide to effective psychosocial and pharmacological interventions (pp. 433-455). New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/med:psych/9780195135947.003.0015

Oerbeck, B. et al (2017). Treatment of selective mutism: a 5-year follow up study, European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Zakszeski, B. & DuPaul, G. (2016). Reinforce, shape, expose, and fade: a review of treatments for selective mutism (2005-2015), School Mental Health.

Citation

Kotrba, A. (2018). Unlocking the Mystery of Selective Mutism. continued.com – Early Childhood Education, Article 23134. Retrieved from www.continued.com/early-childhood-education