Editor's Note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Eco-anxiety: Symptoms and Solutions, presented by Karen Magruder

MSW LCSW-S.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Explain key symptoms of eco-anxiety.

- Describe the prevalence of eco-anxiety among diverse populations.

- List evidence-based treatments for eco-anxiety.

Introduction

Hello, everyone. Thank you for joining me today as we explore the topic of eco-anxiety, how it manifests, and what we, as clinicians, can do about it. Before we dive into the heart of the discussion, let’s take a moment to cover some housekeeping details.

Limitations/Risks

Eco-anxiety is a highly complex topic, and this webinar is designed to provide an introduction to eco-anxiety and some treatment options. It’s important to note that this presentation is not intended to be an exhaustive or all-encompassing exploration of the subject. Eco-anxiety can manifest differently across various cultures and communities, so as practitioners, it’s crucial to exercise cultural humility and acknowledge diverse perspectives. This ensures that we avoid a one-size-fits-all approach and provide care that is sensitive to individual and community needs.

Session Overview

By the end of this session, I hope to achieve the outlined learning outcomes. To set the stage, I’d like to share a bit of my story—how, as a social worker, my professional identity intersected with environmental issues, and how I came to care deeply about and gain knowledge on these topics within a social work context. After that, we’ll explore eco-anxiety by examining its causes, symptoms, and prevalence, particularly among diverse populations. Finally, we’ll delve into clinical interventions that are either evidence-based or show promise in treating and addressing eco-anxiety, with the goal of helping individuals develop effective coping strategies.

What Are Your Burning Questions? (Live Webinar)

Before we get started, I’d like to get a general sense of your questions about eco-anxiety. I see someone caught the intentional use of “burning questions” there—yes, that’s exactly the point. Our house is on fire, after all. I’ve noted a few points to address along the way, and we’ll revisit the rest later. Let’s dive in!

My Story

As promised, I want to provide some context for today’s presentation by sharing my personal and professional journey, particularly how ecological and environmental issues intersect with my work in social services and mental health. I’ve always appreciated the benefits of spending time in nature—the awe, wonder, and mental health boost that comes with being outdoors. Growing up, I valued the beauty of the natural world and tried to be as environmentally responsible as I could, doing things like recycling, reducing waste, turning off lights, and conserving water. These were all small steps to reduce my carbon footprint, but I never really considered the physical environment as an integral part of social work or social service practice.

In my education and early career, we focused on the political, economic, and social environments, but the literal environment wasn’t emphasized in the same way. That began to shift for me as I started seeing not only the benefits I enjoyed from nature but also the challenges and disruptions that environmental issues caused in daily life. For example, living in Phoenix, Arizona, where the heat can be extreme—it’s 110 degrees today as I speak!—I’ve seen firsthand how these conditions can range from small inconveniences, like recycling bins warping in the heat, to major disruptions in daily life.

The turning point for me came during Hurricane Harvey in Texas. At the time, I was living in Dallas and working with older adults in assisted living and nursing facilities. I witnessed the disproportionate impact of the hurricane on this vulnerable population. Many older adults had mobility or health issues, limited support networks, fixed incomes, and a physiological susceptibility to environmental challenges. These factors made them particularly vulnerable during and after the storm. I volunteered at a shelter providing crisis intervention and saw how unprepared the system was to meet their needs. The nonprofit I worked for, The Senior Source, stepped in to provide walkers, adult incontinence supplies, and assistance with continuity of care for home healthcare and medications.

That experience was a wake-up call for me. I realized that social and environmental issues aren’t siloed, with social workers addressing one and environmentalists tackling the other. They’re deeply connected. For instance, as I continued working with older adults, I saw how heat waves strained nonprofits that were trying to bridge gaps in resources, such as installing or repairing air conditioning or providing cooling centers. Older adults, who are less physiologically adaptable to extreme heat, were especially at risk, and it became clear how environmental issues exacerbate social vulnerabilities.

After that lightbulb moment, I pursued more education to deepen my understanding. I earned a certificate in Climate Change and Health from Yale and became involved in the Climate Reality Project through Al Gore’s activism. These experiences helped me educate others about the connections between climate issues and social justice. Now, as a social worker and educator, I focus on treating eco-anxiety, which we’ll discuss more in-depth shortly, while also raising awareness about how clinicians and social service professionals have a critical role to play. Environmental scientists aren’t the only ones who can contribute to solutions. We, too, have skills and expertise that are vital in addressing these intertwined challenges.

Earth Has a Fever

All of that is to say that, in my studies and efforts to better understand these issues and how I could contribute, I’ve come to see it this way: the Earth has a fever. While it’s beyond the scope of this lecture to delve into all the environmental issues we’re facing, I find this simplified analogy helpful. Just as a small increase in my body temperature—from 98.6 to, say, 101 degrees—might seem minor, it makes a big difference in how I feel and function. The same is true for the Earth. Even a few degrees of warming can have profound effects on ecosystems, intensifying disruptions and rippling through the planet’s systems.

While climate change is a major challenge, it’s not the only ecological issue we face. Unfortunately, vulnerable and historically marginalized populations often feel the impacts of these crises first and worst. For example, as I shared earlier, the disproportionate effects of Hurricane Harvey and extreme heat waves in Texas highlighted how environmental challenges exacerbate existing inequities. These realities underscore the need for us to address both the ecological and social dimensions of these problems.

Today's Environmental Injustices

Figure 1 shows some of today's environmental injustices.

Figure 1. Today's environmental injustices.

While it’s beyond the scope of my talk today to provide an exhaustive list of the environmental injustices we face, some key examples include increasing heat waves, the rising intensity of hurricanes, climate-forced migration, and various forms of pollution—whether air pollution, plastic waste, litter, or other contaminants. Other issues include food deserts, where low-income urban communities lack access to fresh and affordable food, and the disposal of toxic waste, such as chemical or nuclear waste. Access to clean and safe water is another critical issue.

These environmental injustices affect not just our clients but many of us as well. They remind us of the interconnectedness of these challenges and the urgent need to address them on both systemic and personal levels.

How Does That Make You Feel?

Given the brief overview I’ve just shared about some of the challenges our Earth is facing, how does that make you feel? Even after just a short discussion of these pressing issues, I’d love to hear your thoughts. If you’re comfortable, please share in the chat how you’re feeling, and I’ll read some of your responses aloud.

I’m seeing a range of emotions here: frightened, anxious, depressed, frustrated, devastated, concerned, helpless, overwhelmed, powerless, worried. Someone mentioned, "The tornado is here," and others shared feelings of anxiety and being uninformed. Thank you so much for sharing. These are powerful and honest responses, and I want to validate and honor these experiences.

It’s certainly not my intention to scare you or ruin your day with this talk. We will absolutely get to solutions and ways to cope. But I think this crowdsourced list of emotions beautifully illustrates the very essence of eco-anxiety. The feelings you’ve shared—anxiety, helplessness, overwhelm, concern—are classic symptoms of eco-anxiety.

For those of you who wanted a clear definition of eco-anxiety, you’ve just captured it in your own words. Eco-anxiety is this collective experience of emotional distress in response to the environmental crises we face. It’s a very real and growing phenomenon, and it impacts not only our clients but also us as professionals. Let’s explore it further.

Eco-anxiety

What is eco-anxiety, exactly? Let’s take a closer look at what this really means. It’s described as a pervasive fear of environmental damage or ecological disaster, largely rooted in the current state of the environment and predictions about the future. While I’ll go into more detail about symptoms in the next slide, this definition captures the core of what eco-anxiety entails.

Importantly, eco-anxiety is increasingly recognized as a distinct area of clinical focus—it’s a real and valid concern. However, I want to clarify that it is not currently defined as a distinct diagnosis in the DSM. When I describe it as a topic that clinicians are focusing on, it’s to emphasize the growing interest in understanding and addressing this issue in a sensitive and appropriate way, even though it doesn’t yet have formal diagnostic criteria.

Common Symptoms

How eco-anxiety is defined and its common symptoms are an amalgamation of insights from recent literature, publications, trainings, and other resources on the topic. Since eco-anxiety isn’t codified in the DSM, it’s a bit fuzzier than conditions with formal diagnostic criteria. However, the way I’ll describe it should help you better recognize some of these symptoms or presentations, whether you see them in clients, loved ones, or even yourself.

Some of the common symptoms include pervasive worry. This isn’t just, "Oh, I went to Karen’s lecture, now I’m briefly worried about the Earth having a fever, and then I move on with my day." Instead, it’s a more enduring sense of worry that doesn’t pass quickly. Anxiety, as the term suggests, can present in familiar ways—physiological responses, rumination, and other manifestations typical of anxiety disorders.

A particularly key and unique aspect of eco-anxiety, which many of you touched on earlier, is the feeling of helplessness, powerlessness, or impotence. That overwhelming sense of having little or no control is a common feature. Frustration and anger are also often present, reflecting the emotional toll of witnessing environmental challenges without feeling equipped to make a significant impact. Additionally, we often see symptoms like sleeplessness and changes in eating patterns, both of which are common when stress or anxiety is heightened.

These symptoms paint a picture of how eco-anxiety manifests and how deeply it can affect people, far beyond a fleeting concern. Recognizing these signs is the first step toward addressing and supporting those experiencing eco-anxiety.

Climate Anxiety

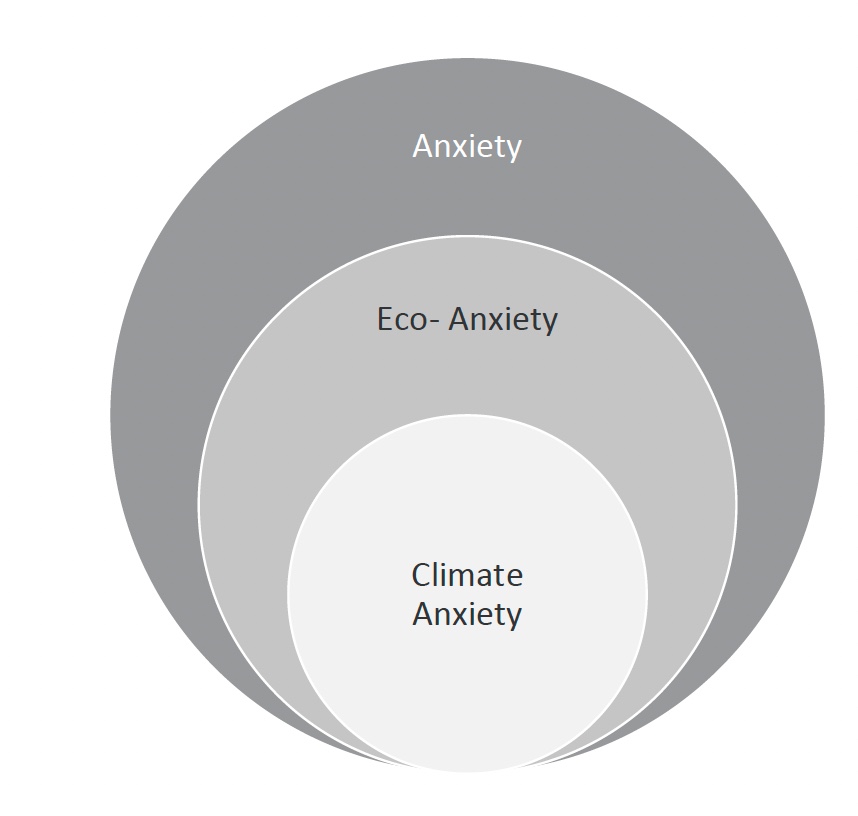

Now, to discuss a few different terms, I’m using the term eco-anxiety. Eco-anxiety is kind of middle-level. In Figure 2, I’ve used this graphic to show that we have anxiety in the largest sphere.

Figure 2. Levels of anxiety.

Of course, you can have targets of anxiety related to a number of different issues. Eco-anxiety is a specific subtype of anxiety where you might feel worried, frustrated, helpless, or concerned about issues related to the environment—anything from pollution and toxic waste to climate change and other environmental injustices or problems, like those shown on the previous slide.

Climate anxiety, in turn, is a specific subtype of eco-anxiety, focused specifically on climate change. Given the scope and urgency of climate change, it’s no surprise that climate anxiety is a very common subtype of eco-anxiety. This type of anxiety often centers on what individuals see in the news about the climate crisis and the overwhelming challenge of processing and dealing with it all.

One of the questions I’ve already seen come in is how eco-anxiety differs from general existential dread. In my clinical and professional opinion, they are certainly related. Eco-anxiety and climate anxiety can spur broader existential questions, and having existential conversations can be an effective way to address them. However, eco-anxiety and climate anxiety are more specific than general existential malaise. Hopefully, that helps clarify the distinction.

There was also a question about discussing the evidence of climate change with clients. I’ll touch on that a bit later, as it fits better with what’s coming up next, but I’ll definitely circle back to it.

To summarize, eco-anxiety differs from climate anxiety in that eco-anxiety is broader, encompassing environmental issues beyond climate change, such as toxic waste or pollution, while climate anxiety focuses specifically on the challenges and threats posed by climate change.

Eco-Grief

Another differential diagnosis worth noting is the distinction between eco-anxiety and eco-grief. Eco-anxiety is very future-oriented—it's about worrying over what is to come. In contrast, eco-grief is more past-oriented, involving mourning the loss of what used to be. People might present with both, and they are certainly interconnected and intertwined. However, identifying which one is the more prominent presenting factor can shape the treatment approach. Just as we treat grief differently from anxiety, we also approach eco-anxiety differently than eco-grief.

This talk focuses on eco-anxiety, so we’ll concentrate on addressing future-oriented worries and how to help individuals cope with them effectively.

Other Related Conditions

A final note on related conditions you might encounter: specific phobias are included in the DSM, and you can reference the diagnostic criteria for those. It’s possible for someone to reach the threshold for a diagnosis of a specific phobia, such as one related to climate change. However, eco-anxiety in the general public tends to be less intense than a phobia. Phobias are often perceived as excessive or irrational—not that this perception is necessarily accurate—but eco-anxiety usually falls on a spectrum from realistic concern to potentially more apocalyptic views. For example, as someone mentioned in a question, how do we address individuals with an apocalyptic perspective that may not be rooted in reality? This highlights the spectrum of eco-anxiety, with phobias existing on the more intense end. However, most eco-anxiety doesn’t rise to the level of a diagnosable phobia.

Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) is another condition to distinguish from eco-anxiety. SAD is often tied to limited sunlight during certain seasons and affects individuals in a predictable, cyclical pattern. Eco-anxiety, by contrast, is not seasonal and is related to ongoing concerns about the natural environment.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) encompasses a broader range of worries, while eco-anxiety is more specific and targeted. Unlike phobias, which may be perceived as irrational, many fears tied to eco-anxiety are well-founded. Concerns about environmental crises—such as animal depopulation, melting glaciers, sea-level rise, extreme weather, and coral bleaching—are grounded in real and observable phenomena. Climate change coverage has shifted from distant "doom-and-gloom" warnings to the unsettling reality that it is already unfolding before our eyes.

One key takeaway, and a spoiler for a treatment strategy, is that validating these concerns is essential. To some degree, eco-anxiety reflects real challenges, and it’s important to acknowledge that it’s not excessive or irrational to feel worried about the climate and the state of our environment. However, the lack of formal inclusion in the DSM can lead to eco-anxiety being underrepresented or misdiagnosed, making it harder to address in clinical settings. This underrepresentation underscores the need for clinicians to approach eco-anxiety with sensitivity and understanding.

Prevalence

Here’s what we know about the prevalence of eco-anxiety. Since it’s not a distinct disorder in the DSM, it’s challenging to measure consistently. However, if eco-anxiety were taken into account with more intentionality in clinical or healthcare settings, scholars and clinicians could gather more reliable statistics. Even with these limitations, reports indicate that eco-anxiety is a growing concern, especially among younger populations.

For instance, "climate emergency" was Oxford Dictionary’s word of the year not long ago, reflecting how pressing this issue has become. In 2021, there was a staggering 4000% increase in Google searches for "climate anxiety," illustrating how awareness and concern are rising. Large-scale surveys, like those conducted by Yale’s Institute for Climate Change, offer additional insights. A recent global survey of over 10,000 young people aged 16 to 25 found that 84% were moderately or extremely worried about climate change. Similarly, a study of the adult U.S. population revealed that 43% of Americans were alarmed or concerned about climate change, and another report indicated that two-thirds of the U.S. population were somewhat or very worried about it.

These figures show that eco-anxiety is not only gaining attention but becoming increasingly relevant in people’s lives. Greta Thunberg’s iconic statement, “Our house is on fire,” resonates deeply, as the concern spans generations. For example, parents may become preoccupied with fears about the future their children or grandchildren will inherit.

Although eco-anxiety isn’t easily measured—there’s no standardized question in the census or in most clinical assessments—estimates suggest that anywhere from 40% to 80% of the U.S. population experiences some level of worry about environmental issues. This means it could reasonably surface in therapeutic contexts, warranting awareness and preparedness among clinicians.

Impacted Populations

Environmental issues affect many, if not all, of us. However, as I mentioned earlier, the impact tends to fall disproportionately on vulnerable and marginalized populations. Eco-anxiety is not just a U.S. phenomenon; it has been documented across the world, including in Canada, Europe, Australia, the Pacific Islands, and Asia. I would venture to say that some degree of eco-anxiety exists everywhere there is concern about environmental issues. Unfortunately, those who have contributed the least to problems like climate change or pollution often suffer the most severe and earliest consequences. These populations face greater exposure to environmental issues, heightened vulnerability, and lower adaptive capacity—the ability to cope and recover from these impacts.

That being said, eco-anxiety is commonly observed among younger people, as reflected in the literature. Youth are often exposed earlier to dire messages about climate change and other environmental injustices, and they arguably have the most at stake. Since they will live to see the long-term effects of environmental crises, they may feel a heightened sense of urgency and responsibility, making them particularly vulnerable to developing eco-anxiety. That said, anyone can experience eco-anxiety, regardless of age or background.

Overview of Interventions

Let’s talk about solutions and interventions for eco-anxiety. This is still an emerging area of focus, with much of the literature having been published since 2020. In my work through a DSW program and other research efforts, I’ve systematically reviewed what scholars and clinicians are identifying as effective ways to address eco-anxiety in therapy. Here’s what I’ve found:

The first and most important step is validation. Recognizing a client’s concern about environmental issues as legitimate is essential. It’s not about labeling someone as an alarmist or dismissing them as a “fragile snowflake.” Often, these concerns are rooted in real evidence of current and worsening environmental issues. Expressing empathy and maintaining a non-judgmental attitude allows clients to feel heard and supported. While eco-anxiety can sometimes involve cognitive distortions that may need to be addressed, most of the time, it’s a natural and valid reaction. Think about Maslow’s hierarchy of needs—food, water, and shelter are fundamental, and when these are threatened, anxiety is a normal response. Validating that anxiety aligns with this reality.

Returning to a pre-submitted question about discussing evidence of climate change with clients: as with any issue, this should be client-led. Meeting clients where they are is crucial. If the topic arises organically, sharing sound, evidence-based knowledge can help validate their concerns or potentially support cognitive reframing. However, this should always be done without imposing an agenda or overwhelming the client with facts unless it feels helpful and appropriate at the moment.

Taking action is another powerful intervention. A hallmark of eco-anxiety is the sense of helplessness. Helping clients regain a sense of control—whether through small, meaningful actions like cultivating a garden, volunteering, or engaging in political activism—can alleviate this feeling. It’s not about solving all the world’s problems as one individual but identifying ways to act in alignment with personal values and passions. For some, this might be through education, art, writing, or science. The key is allowing clients to choose how they engage, rather than prescribing specific actions.

Social support is also invaluable. A strong support network, whether through friends, family, or community groups, can provide understanding, encouragement, and connection. Beyond individual relationships, there are emerging resources like climate cafés—similar to death cafés—where people gather to share their experiences and feelings about environmental issues. These kinds of specific support groups are growing in cities across the U.S. and can offer spaces to process eco-anxiety collectively.

Ecotherapy, or nature-based interventions, is another effective approach. For individuals who associate nature with danger due to experiences like hurricanes or tornadoes, reestablishing a positive connection with the natural world can help. This could involve spending time in parks, hiking, or even incorporating greenery into indoor spaces, such as filling an office with plants. Restoring a balanced relationship with nature can shift perceptions from fear to appreciation and healing.

Mindfulness is a well-established, evidence-based intervention that applies here as well. Eco-grief tends to focus on the past, while eco-anxiety is future-oriented. Mindfulness, with its emphasis on non-judgmental awareness of the present moment, can help clients ground themselves, recenter, and break out of cycles of rumination.

Cognitive reframing is another promising intervention. If a client’s worries are disproportionate or unrealistic, reframing can help create a more balanced perspective. For instance, addressing "should" statements tied to eco-guilt—like “I should be doing more to reduce my carbon footprint”—can encourage clients to acknowledge the efforts they are already making and focus on what is within their control. This technique can foster healthier, more adaptive thought patterns.

Finally, I want to emphasize again the importance of validation. While identifying cognitive distortions is important, it’s equally critical not to shame someone for their response to what is, in many cases, a valid and natural reaction to a real threat. Validation should remain the foundation of any intervention.

Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT)

I see a lot of value and promise in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for treating eco-anxiety. I’ll be presenting at a conference about this in October with a former student of mine. ACT is a well-established, empirically supported psychotherapy that focuses on helping clients accept their current thoughts and feelings rather than getting stuck in past events or excessively worrying about the future.

One of ACT's key strengths is its emphasis on mindfulness. ACT encourages clients to live in the present moment and engage fully with their current experiences, helping them step back from rumination and anxiety while fostering psychological flexibility. ACT also promotes committed action, encouraging clients to take meaningful steps aligned with their values, even in the face of difficult emotions or circumstances.

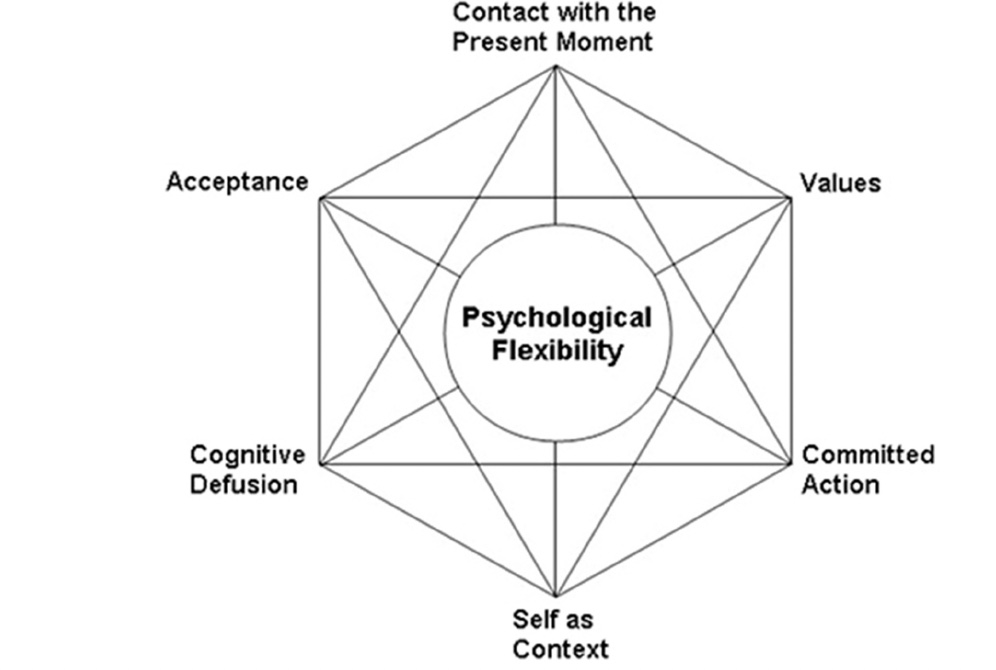

I find ACT’s hexaflex model for psychological flexibility (as shown in Figure 3) particularly useful when addressing eco-anxiety. It provides a framework for helping clients navigate distressing emotions, build resilience, and make choices that align with their values in a way that feels purposeful and empowering. This combination of acceptance, mindfulness, and committed action makes ACT an especially promising approach for addressing the unique challenges of eco-anxiety.

Figure 3. ACT's hexaflex model of psychological flexibility.

As I’ve already mentioned, mindfulness is a valuable tool, and it’s a key component of ACT. Identifying values is another excellent activity in the context of eco-anxiety. ACT encourages a degree of acceptance around distressing thoughts and emotions, allowing clients to acknowledge their feelings without becoming overwhelmed by them.

What I particularly appreciate about ACT is how it helps align values with committed action. It’s not just about being present, accepting feelings, and defusing unhelpful thoughts—it’s about using that clarity to take meaningful action in alignment with one’s values. This process can be incredibly empowering and is especially effective in addressing the feelings of helplessness that are so often a hallmark of eco-anxiety. By connecting values to action, ACT provides a pathway to move forward with purpose and resilience.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

As I mentioned earlier when discussing cognitive reframing, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has also been applied to eco-anxiety. One of its strengths is that it’s an evidence-based approach for generalized anxiety and specific phobias, which, as we’ve discussed, share some overlap with eco-anxiety. Cognitive reframing can be a helpful tool for addressing unhelpful thought patterns, but behavioral activation stands out as particularly effective.

Behavioral activation focuses on engaging clients in specific, tangible activities that can improve their mood and help them feel more grounded. These activities might include self-care practices, spending time in nature, or other actions that promote a sense of well-being and resilience. By helping clients identify and engage in meaningful activities, CBT can support them in getting into a better headspace.

That said, it’s important to approach eco-anxiety with care and avoid giving the impression that we are being judgmental or invalidating legitimate concerns. Balancing validation with encouragement toward adaptive behaviors is key to providing effective support.

Self-Care: The UP STREAM Model

I also want to share the UPSTREAM model, a framework I developed to encapsulate best practices for supporting ourselves and our clients who might be experiencing eco-anxiety. As an educator, I love snappy mnemonics and acronyms to make these concepts easier to remember. This model is designed to summarize strategies for addressing eco-anxiety effectively:

U – Understanding and Self-Compassion: This reflects the importance of validation and recognizing that it’s okay to experience distress. Practicing self-compassion helps us acknowledge and manage these feelings without judgment.

P – Participating in the Solution: Taking action is empowering. Encourage clients to decide what this looks like for them based on their own interests, skills, and comfort levels. For example, instead of suggesting specific actions like voting for a particular candidate, ask what resonates with them and aligns with their values.

S – Self-Talk: Addressing and limiting negative self-talk or cognitive distortions that can amplify valid concerns is key. Helping clients identify and reframe these patterns can reduce the intensity of their anxiety.

T – Trauma Healing: While this talk focuses on anxiety, eco-anxiety and eco-grief are interconnected. Many individuals have experienced environmental injustices or personal trauma related to these issues. Supporting clients in processing and healing from these experiences can be essential.

R – Reducing Isolation: Building and maintaining social support is critical. Whether through relationships or participation in community or support groups, reducing isolation can foster resilience and emotional well-being.

E – Ecotherapy: Nature-based interventions help restore a positive relationship with the natural world. Activities like spending time in parks or incorporating greenery into daily spaces can counteract the fear and disconnection that eco-anxiety often brings.

A – Acts of Self-Care: Self-care practices are crucial for maintaining emotional balance and keeping one’s “cup full.” Encouraging clients to prioritize activities that nurture them helps sustain their mental health.

M - Mindfulness: Engaging in present-focused, nonjudgmental awareness is a powerful tool for managing eco-anxiety. Mindfulness helps ground clients and prevents them from becoming overwhelmed by past traumas or future fears.

This model provides a comprehensive and easy way to remember actionable steps for addressing eco-anxiety. We’ve now covered the symptoms of eco-anxiety, described its prevalence, and explored various potential treatments, including this model, to help guide effective intervention.

Summary

To wrap up, let me summarize the key points we’ve discussed.

Eco-anxiety involves feelings of worry, fear, and helplessness related to climate change and other environmental degradation. It is often accompanied by stress, insomnia, a sense of loss, and other related challenges. While eco-anxiety is not officially included in the DSM, tools are being developed to screen for and better understand it. However, it remains less defined compared to other mental health conditions. Even so, a significant portion of people—anywhere from 40% to 80% of Americans—express some level of concern about environmental issues. Among these, a smaller but meaningful subset may need clinical intervention, though it’s likely more prevalent than we might initially assume.

Eco-anxiety is not limited to the United States; it is a global phenomenon, with higher prevalence among younger generations and communities directly impacted by climate change. Indigenous populations and residents of vulnerable regions often experience greater levels of eco-anxiety. This is linked to three elements of vulnerability: exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity. For example, people living in coastal areas are more exposed to rising sea levels, while certain groups, such as children and older adults, are more biologically sensitive to specific environmental issues like air pollution or extreme heat. Additionally, those with limited social, economic, or political resources often have reduced adaptive capacity, making it harder to cope with environmental challenges. These compounded vulnerabilities contribute to higher levels of eco-anxiety in disenfranchised populations.

Younger generations are particularly affected, having grown up with ongoing messages about climate change and environmental degradation. They also face a significant personal stake in how these issues will unfold over the coming decades, adding to the emotional burden they carry.

Eco-anxiety is still an emerging area of focus, offering clinicians opportunities to conduct further research and develop tailored interventions. While many traditional approaches to anxiety are effective, there are specific strategies that show promise for addressing eco-anxiety. Validation is key, providing compassion and reassurance that these feelings are a normal and natural response to real threats. Brief psychoeducation about the validity of their concerns can also help. Encouraging clients to take meaningful action within their circles of influence can help address feelings of helplessness, while social support reduces isolation and fosters a sense of community. Mindfulness practices can assist clients in staying present and managing anxiety that is often future-oriented. Evidence-based therapies like Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) are particularly helpful, using interventions such as cognitive reframing, behavioral activation, and values-aligned action.

While the exploration of other modalities, such as existential therapy and narrative therapy, is ongoing, many tools designed for anxiety, in general, are effective starting points. Ultimately, addressing eco-anxiety involves a mix of validation, action, support, and mindfulness to help individuals navigate these complex and deeply felt concerns.

Questions and Answers

How do you deal with an apocalyptic stance from young people?

It’s important to think of this as a spectrum. Some individuals might not be concerned at all, and perhaps they should be, as increased awareness could lead to meaningful action. On the other end of the spectrum, some may adopt an overly apocalyptic view that might not align with reality and may require gentle balancing. A certain level of anxiety is valid and expected given the circumstances. Accepting and processing these feelings is essential, followed by coping strategies to help manage and minimize distress. For individuals with unrealistic views, sensitive and balanced cognitive reframing can be helpful in addressing distortions without invalidating their concerns.

Why are environmental conditions labeled as injustices?

Environmental conditions are often considered injustices because vulnerable and historically marginalized communities tend to suffer first and worst from these issues. For example, environmental racism is a well-documented phenomenon where communities of color are more likely to have undesirable environmental conditions, such as toxic waste disposal sites, in their neighborhoods compared to affluent communities. Urban heat islands provide another example—lower-income residents living in city centers often experience higher temperatures due to reduced tree cover and increased concrete and emissions, unlike residents in wealthier suburbs. While some environmental problems affect everyone, these justice-related elements disproportionately impact marginalized groups.

Can environmental issues be coded as a focus of clinical attention?

Yes. In the DSM-IV, environmental problems were often addressed under Axis IV. While the multiaxial system is no longer part of the DSM-5, there is a section in the back for "Other Conditions That May Be a Focus of Clinical Attention," which includes a code for environmental issues. While not a formal diagnosis, this allows clinicians to note eco-anxiety as a relevant factor in therapy. For billing purposes, some clinicians use codes for unspecified anxiety disorders if eco-anxiety is a prominent issue requiring clinical attention.

How should clinicians handle eco-anxiety that ranges in severity?

Eco-anxiety can vary significantly. Some clients may only bring it up occasionally, perhaps after reading a distressing news article, requiring brief validation and coping strategies like behavioral activation or limiting news intake. Others may experience more pervasive and severe eco-anxiety that needs ongoing attention. Tailoring the approach to the individual’s needs is essential.

What about Gus Speth’s quote on environmental problems and human attitudes?

Speth’s quote highlights that many of the world's top environmental problems—biodiversity loss, ecosystem collapse, and climate change—are human-caused and rooted in attitudes like selfishness, greed, and apathy. Addressing these issues requires not just scientific and technological solutions but also cultural and spiritual transformation. For those interested in actionable solutions, the book and website Drawdown provide a comprehensive list of top solutions for climate and environmental issues. These solutions are multifaceted, involving science, technology, education, and awareness to address the complexity of the problem.

What are the limitations of CBT when addressing eco-anxiety?

While CBT can be very effective, there’s a risk that cognitive reframing might be perceived as invalidating by clients if their concerns are dismissed as "irrational." Eco-anxiety often stems from real and pressing environmental threats, so it’s critical to use clinical judgment to balance reframing with validation. Avoiding judgment ensures the intervention remains compassionate and effective.

How can clinicians help clients with perfectionism around their environmental impact?

This is often referred to as "eco-guilt." Clients may struggle with the idea that they can’t completely mitigate their environmental impact, or they may find that some actions are not feasible in their lives. Encouraging clients to explore their values, as suggested in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, can be a good starting point. Helping them balance their values of sustainability with a reasonable and achievable lifestyle is essential. Acknowledge their efforts, emphasize that they’re doing the best they can, and remind them that individual actions are part of a larger collective effort. Encourage grace and self-compassion, as no single individual can solve the issue alone.

Can eco-anxiety show up as an OCD theme or other compulsive disorder?

Yes, eco-anxiety can manifest as an OCD theme. Documented cases include obsessions and compulsions related to environmental impact, such as compulsively checking light switches or faucets to save energy or water. In such cases, traditional OCD interventions remain effective, even if there’s an environmental element involved. Similarly, eco-guilt can sometimes be a factor in hoarding disorder, where individuals feel conflicted about discarding items due to concerns about waste. Talking through the impacts of their choices—whether recycling, donating, or discarding—is a compassionate way to address these concerns.

I encourage you to reach out if you have more questions. You can find me on LinkedIn or email me at karenmagruder@uta.edu. Thank you so much for your thoughtful questions and participation, and I hope this session provided useful insights.

References

Please refer to the additional handout.

Citation

Magruder, K. (2024). Eco-anxiety: Symptoms and solutions. Continued.com, Article 85. Available at www.continued.com/psychology