Editor's Note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Providing Behavioral Health Treatment to LGBTQ+ Populations: Introductory Ethical and Clinical Considerations, presented by Andrew Arriaga, PsyD.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Identify key terms, concepts, and empirical findings relevant to the understanding of LGBTQ+ people and their experiences.

- Identify common issues often reported by LGBTQ+ people in psychotherapy.

- Identify therapeutic challenges that may arise in psychotherapy with LGBTQ+ people.

Risks and Limitations

Today, I’d like to begin by discussing some of the risks and limitations we face. First, it’s essential to explore individual and cultural considerations before pursuing any treatment plans or interventions. Much of this is likely covered in your training—whether through graduate programs or hands-on clinical work—but these factors should always be carefully examined, often with supervision, to address potential concerns ahead of time.

The availability of gender-affirming therapeutic or medical support can vary widely depending on agency policies, local laws, and federal guidelines. As many of you are probably aware, gender-affirming care laws differ significantly across the United States. Some of what we discuss today may not directly apply to your specific region. However, that doesn’t lessen the importance of these concepts. Laws and federal guidelines are constantly evolving, so it’s critical to stay informed. Continuing education and supervision are highly recommended when working with LGBTQ+ populations. For some, this is a core focus in their work—particularly in behavioral health—but others may not have had as much exposure to these communities in their training or practice.

In light of this, it’s always beneficial to seek out further courses, like this one, and connect with supervisors who can offer broader perspectives and open up space for discussion. This approach is invaluable when serving populations with whom you may have limited familiarity. Since this is an introductory course, we won’t be able to dive deeply into all the health disparities and interventions across the lifespan for LGBTQ+ individuals. I’m sure many of you anticipated this, given the nature of the course, but it’s worth reiterating. Hopefully, in the future, I’ll have the opportunity to return, and we can take a deeper dive into these disparities and the interventions designed to address them. As you move forward from this course, keep in mind the importance of continued education and supervision. These will ensure you develop a thorough understanding of the health disparities LGBTQ+ individuals face and the appropriate interventions for supporting them in clinical settings.

Ethics Codes

As you know, behavioral health providers come from diverse training backgrounds, so many of us have encountered some or all of these codes in one way or another throughout our education. I strongly encourage you to always refer back to your specific ethical code when faced with ethical questions or decisions. While we all generally receive training grounded in similar ethical principles, there may be nuanced differences depending on the field in which you work.

Below are links to Ethics Codes for some of the major behavioral health professions. Please ensure you always refer to your own ethical code.

- AAMFT: https://www.aamft.org/Legal_Ethics/Code_of_Ethics.aspx

- ACA: https://www.counseling.org/resources/aca-code-of-ethics.pdf

- APA: https://www.apa.org/ethics/code

- NBCC: https://nbcc.org/assets/ethics/nbcccodeofethics.pdf

- NAADAC: https://www.naadac.org/code-of-ethics

- NASW: https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English

Ethical Considerations

I’d like to begin by focusing on some general ethical considerations when working with LGBTQ+ individuals. As I’ve mentioned, ethical codes across behavioral health professions share commonalities, and many of us are familiar with at least a few of them. These codes typically require that, as professionals, we remain competent in serving a diverse range of clients, regardless of specific backgrounds. This applies not only to LGBTQ+ individuals but to all clients we encounter. It’s a vital point to keep in mind.

It’s natural to feel overwhelmed when faced with clinical situations that are unfamiliar or outside our comfort zones. However, a key ethical consideration is recognizing that our role as behavioral health professionals is to hold space for clients from all walks of life. We have the foundational skills to do this. So, if you're considering working more with LGBTQ+ populations but feel uncertain about your level of competence or confidence, I encourage you to remember that these ethical principles are already a part of your professional training.

That said, we also acknowledge that working with LGBTQ+ clients can be challenging for clinicians who may hold biases or discomfort with certain identities. This issue isn’t limited to LGBTQ+ clients; it can also apply to individuals from different religious, racial, or ethnic backgrounds. However, I always remind colleagues that the core of this work is about adhering to the same ethical standards you would apply to any client. So, whenever you find yourself making clinical decisions, always refer back to the ethical codes of your profession.

Important Ethical Concepts

I’d like to focus on a few ethical concepts that I find particularly important when working with LGBTQ+ clients. Many of these terms, if not all, will likely be familiar to you, but let’s explore them in this context.

First, autonomy. It’s crucial to remember that, just like with any client, LGBTQ+ individuals know themselves best. Gatekeeping care can be a significant concern, especially when clients feel misunderstood or sense that a clinician is steering them in a direction misaligned with their experiences. At the end of the day, we must trust that our clients understand their own needs.

Next, beneficence and nonmaleficence—core values we’re all familiar with in behavioral health. These principles remind us to do right by our clients, to help them navigate challenges in ways that are both productive and safe. Above all, we must ensure we’re not causing harm. When facing ethical dilemmas, it can help to simplify the situation: Am I doing everything within my ability to serve this person? Is there any risk that my actions could harm them? Avoiding decisions that could cause harm is especially critical when working with LGBTQ+ individuals, as there are often additional nuances to consider, which we’ll dive into later.

Fidelity and veracity—respecting others' rights and dignity—may seem straightforward, but they are fundamental to our work. This includes ensuring confidentiality and creating a safe space for LGBTQ+ clients, whether they are currently identifying as such or not. It’s essential that they feel comfortable exploring their experiences and unique challenges in an environment that honors their dignity and listens without judgment.

Lastly, justice. A significant aspect of working with LGBTQ+ individuals often revolves around social justice. Some of us are engaged in anti-racist training, social equity efforts, or advocacy work within our communities, and these elements can also shape our clinical practice. For LGBTQ+ communities, social justice concerns frequently arise, given the ongoing legal and social barriers that impact access to care and equality. Recognizing and supporting clients on their journey toward justice, both in and outside of the therapy room, is invaluable. Our role as clinicians, from an ethical standpoint, is to align with and support those efforts, recognizing the broader social and legal issues that continue to affect these populations.

Key Terms

Let’s dive into some key terms and concepts. Some may be familiar, and a few might feel quite straightforward, but it’s useful for all of us to refresh our understanding, especially as some of these terms carry nuances that differ from how they’re often used in everyday language.

- gender identity: This refers to how a person perceives themselves—as a man, a woman, both, neither, or somewhere along the spectrum. Essentially, it’s about how individuals define themselves and what they choose to call themselves. You may hear terms like cisgender man, transgender woman, non-binary, or agender, all of which relate to gender identity.

- gender expression: This differs from gender identity. Here’s where we start to get into the nuances of language, as these terms are often used interchangeably in everyday conversation. However, from a clinical and research standpoint, it’s important to distinguish between them. Gender expression refers to how people outwardly communicate their gender identity through behavior, clothing, hairstyles, voice, and overall presentation. For example, you might hear someone described as presenting masculinely, femininely, or with an androgynous expression. These terms reflect aspects of gender expression, rather than gender identity itself.

- anatomical sex: This refers to physical attributes such as external genitalia, sex chromosomes, gonads, hormones, and internal reproductive structures. These are typically the biological markers used to assign sex at birth, which leads us to the next term.

- sex assigned at birth: This is determined by a medical professional based on the visible physical characteristics of a newborn. Typically, this assessment is made by visual examination of external genitalia, such as assigning male if a baby is born with a penis. However, like gender, sex is a complex concept, and this visual method of assigning sex can sometimes oversimplify the biological variations that exist.

- sexual/romantic attraction: Generally, this refers to a person’s emotional or sexual attraction to people of the same or different genders. You may also encounter the term sexual orientation, which is often used interchangeably in this context. While these terms overlap in casual conversation and even in some clinical spaces, it’s helpful to clarify that we’re talking about attraction in both romantic and sexual senses here.

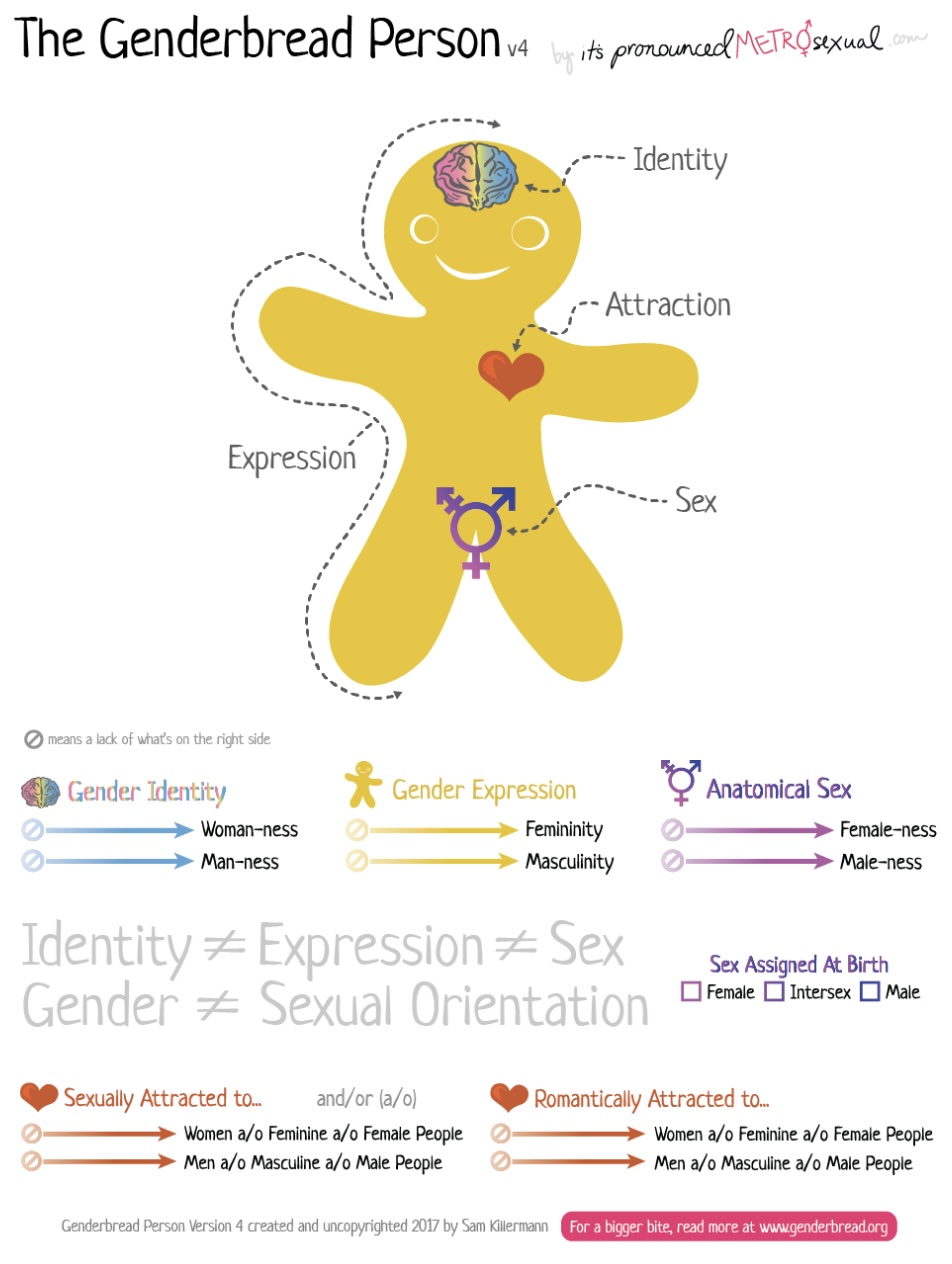

The Genderbread Person

I want to take a moment to introduce the "Genderbread Person." There have been many versions of this circulating for over a decade, but it's a useful tool in clinical work to highlight the differences between these terms and delve into the nuances. It helps explain to clients—whether they are LGBTQ+ or simply exploring their identities—how gender identity, gender expression, and sex assigned at birth can intersect and diverge in unique ways.

Figure 1. The Genderbread Person. Image Source: genderbread.org – CC Universal Public Domain Dedication

When I work with clients using the Genderbread Person, it can also be helpful for parents or family members in therapy, especially those with LGBTQ+ loved ones or those trying to become more supportive. I usually begin with gender identity, as we discussed earlier. This refers to a person’s internal sense of self—how they see themselves and what they prefer to be called. Terms like man, woman, and non-binary are often associated with gender identity.

Next, I move to gender expression. The key point here is that gender expression is how we outwardly communicate our internal identity to the world. Clothing plays a big role in this, but so do other personal choices in style and behavior. For instance, some might assume that identifying as a woman means you should wear dresses and makeup, but that’s simply not the case. If you prefer sweatpants and don’t like makeup, that’s perfectly valid. The takeaway here is that gender identity and expression don’t necessarily predict one another. A feminine man or a masculine woman, whether LGBTQ+ or not, is entirely possible. These are separate constructs, and understanding this is crucial for psychoeducation.

When we talk about anatomical sex, we’re shifting into the more medicalized terminology—terms like male, female, and intersex, which refer to physical characteristics. This leads into sex assigned at birth, where a newborn’s sex—often labeled as male or female— is assigned by a medical professional based on external genitalia. However, as we’ll discuss, this can be more complex, especially in cases of intersex individuals.

Now, an important distinction to make is between gender identity and sexual orientation. Sexual or romantic attraction to others has no bearing on one’s gender identity. For instance, if a cisgender man—someone assigned male at birth who identifies as a man—is attracted to both men and women, that has no direct connection to his gender identity. Attraction, whether sexual or romantic, exists as a separate construct.

This distinction is especially important because, in public discourse and media, there’s often confusion between gender identity and sexual orientation. Trans and gender-diverse individuals are frequently lumped together with queer people, which can blur the lines between these concepts. The Genderbread Person graphic highlights this beautifully, illustrating that identity, expression, sex, and orientation are distinct elements.

Understanding these concepts allows clients to gain clarity about their own experiences: Is this about my gender? How I present myself? Or is it about who I’m attracted to? Each is its own construct, and recognizing this helps break down confusion and fosters deeper self-awareness.

Additional Key Terms

Let’s go over some additional key terms. I’ve included these because, especially in work with younger people or those who are more comfortable discussing LGBTQ+ issues, you may encounter terms that are unfamiliar or used in shorthand. Some of these may seem elementary, and you’ve likely heard them many times before.

- heterosexual: Most of us are familiar with this term or the shorthand “straight” or “hetero.” It refers to someone who experiences sexual, romantic, or emotional attraction to people of a different gender. Historically, it’s been defined as attraction to the "opposite" gender, but since gender is now understood as a spectrum, we try to move away from that language and be more mindful of gender diversity.

- bisexual: This term, with shorthand “bi,” refers to a person who experiences sexual, romantic, or emotional attraction to their own gender as well as to others. Some may assume this means attraction to men and women only, but bisexuality can also include attraction to non-binary or agender individuals. So, defining bisexuality strictly as attraction to men and women is exclusionary. Instead, we acknowledge that it means attraction to the same gender and others.

- pansexual: Shorthand “pan,” refers to sexual, romantic, or emotional attraction to individuals regardless of their gender identity or sex assigned at birth. This broader concept of attraction extends beyond specific gender categories and can include an openness to many, or all, gender identities.

- aromantic and asexual: Often shortened to “aro” and “ace,” these terms are frequently heard together, especially when working with younger clients. Someone who identifies as aro-ace experiences little to no romantic or sexual attraction. However, it’s important to note that individuals on these spectrums may still experience some attraction but don’t feel the need to act on it in the way others might.

- intersex: This refers to individuals born with chromosomal or physiological variances, including ambiguous genitalia. Sex assigned at birth is often based solely on external genitalia, but as we know from biology, sex involves more than just what is visible at birth. Hormones, chromosomes, and reproductive structures all play a role in defining sex, and these factors may not always align with the assigned label. Intersex people exist, and their experiences are distinct from those of individuals assigned male or female at birth. There’s a broader ethical conversation about the practice of assigning sex at birth based on genitalia alone, but that’s a topic for another day.

- transgender: Shortened to “trans,” is a term you’ve likely heard in many contexts—whether in the news, schools, or clinical practice. It’s often used as an umbrella term to describe individuals whose gender identity does not align with their sex assigned at birth. For example, a transgender man is someone who was assigned female at birth but identifies and lives as a man. A transgender woman is someone assigned male at birth who identifies as a woman. It’s important to recognize that within the trans community, individuals may use more specific terms for themselves, such as trans man, trans woman, or trans girl. Some may even prefer not to use the term "trans" at all and simply identify as a man or a woman. Checking in with clients about the language they prefer is crucial.

- gender binary: This is the social system that assigns everyone to be raised as a boy or girl based on their sex assigned at birth. This rigid perspective of gender assumes that male and female are the only two options. However, we know that non-binary or genderqueer individuals exist—people who don’t identify strictly as male or female. Gender fluidity, which refers to a flexible range of gender expression and identity, can be confusing for some who aren’t used to thinking of gender as fluid.

It’s common to hear even more unfamiliar terms when working with younger individuals. It’s important to remember that, ultimately, the client’s view of their own identity and the language they prefer is what matters most—regardless of what you may have learned in a class or even here. While we’ve covered some typical terms for familiarity’s sake, it’s crucial to let our clients lead the way in how they identify and express themselves.

Some people may feel different on different days, choosing to express themselves in a variety of ways. For example, one day they may enjoy wearing dresses, and another day they may prefer a more masculine presentation with jeans and sneakers. This doesn’t necessarily reflect their gender identity but could simply be an expression of their fluid identity. With that said, the language around gender and sexual orientation is constantly evolving. It’s always important to follow the lead of your clients and ask directly if you’re unsure. Simple questions like “What would you like me to call you?” or “Do you have a preferred pronoun, name, or gender identity?” can make an LGBTQ+ client feel truly seen and heard.

Why is This Topic Important

Why is this topic important? I’m sure many of you could think of several reasons off the top of your head, but I’d like to highlight a few key ones that I’ve found particularly motivating in this field. These reasons underscore why we should be competent in this work—or at least work toward that goal.

As clinicians, we have an ethical duty to be prepared to serve individuals from all backgrounds. This means being aware of terms and concepts that are central to LGBTQ+ experiences, so we can create a welcoming and inclusive space for these clients. Familiarizing ourselves with these terms ensures that we are ethically prepared to support them.

Additionally, awareness of LGBTQ+ identities and the social issues within these communities continues to grow. You’ve probably noticed this yourself—there’s increasing visibility around queer and trans people. By “queer,” I’m referring to those who identify as sexual minorities, such as gay, lesbian, bisexual individuals, and more. As society becomes more knowledgeable, we often see an increase in the presentation of these identities in clinical spaces, as people feel more comfortable bringing these aspects of themselves into therapy.

LGBTQ+ individuals also face a unique set of interpersonal and intrapersonal stressors, which need to be carefully considered in clinical work. I’ll walk through some of these stressors and the theoretical background that explains why they exist. Because of these increased stressors, LGBTQ+ people continue to experience disproportionately higher rates of health and wellness disparities—far exceeding those of majority populations.

LGBTQ+ Identity Statistics

Let’s go over a few statistics about identity and where things stand today based on the most recent data. Analyses conducted by the Williams Institute, using 2020-2021 data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System—a major study conducted most years—revealed some notable findings about identity. Even I was a bit surprised by some of these, but it's heartening to see these shifts.

For example, 36% of respondents in the Southern U.S. identified as LGBTQ+, making it the largest regional population compared to the Northeast, Midwest, and Western states. This was unexpected for me, as someone from the South and Texas, but it’s encouraging to see more openness in this region, especially considering the political and cultural challenges that LGBTQ+ people often face in the Southern United States.

Additionally, almost one in six adults aged 18 to 24 identify as members of the LGBTQ+ community. I was pleasantly surprised by this as well. Of course, there are often heated discussions around this statistic—questions like, "Why are more young people identifying this way? Is there a rise in people becoming queer or trans?" In my opinion, much of this can be attributed to increased social acceptance and visibility for Gen Z and Gen Alpha, leading to greater comfort in openly identifying as LGBTQ+.

As for state-level data, California has the largest number of LGBTQ+ adults, with about 1.5 million. It’s also worth noting that, currently, the U.S. Census does not include questions about sexual orientation or gender identity, despite various proposals over the years. As a result, we rely heavily on studies conducted by universities and research institutes to provide this data.

Minority Stress Theory

Let’s start with a bit of theory. Ilan Meyer’s Minority Stress Theory is a framework you’ll often encounter in research and work with LGBTQ+ people. It posits that these populations face unique intra- and interpersonal stressors, which contribute to poorer health and wellness outcomes, beyond what is typically experienced by majority populations. When I talk about intrapersonal and interpersonal stressors, I’m referring to the stress that arises from interactions with others or from being in negative environments.

Interpersonal stressors include experiences like discrimination, microaggressions at work, or being denied services. This can be explicit or policy-driven and doesn’t always involve direct one-on-one discrimination. Intrapersonal stress, on the other hand, may be less familiar, especially to those who haven’t struggled with issues like shame or identity. LGBTQ+ individuals often face stress from internal conflicts, fear, or confusion when acknowledging their identities.

One common form of intrapersonal stress is internalized phobia, where an LGBTQ+ person begins to internalize negative messages from transphobic or homophobic encounters and directs that negativity toward themselves. This internalized negativity can be profoundly impactful and is unique to these populations. Meyer’s theory has been foundational in LGBTQ+ health and wellness research and is the basis for thousands of studies. The theory has also expanded to include other aspects of identity that compound stress, such as race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic background. Staying informed on the latest research and theoretical perspectives is crucial for engaging in this work, even if you’re not reading research articles all the time. Checking in occasionally can be helpful.

LGBTQ+ Barriers to Care

LGBTQ+ individuals often face significant barriers to care, sometimes even before measurable health impacts arise. Many postpone or avoid medical or behavioral healthcare altogether—even when dealing with serious issues like infections, suicidal ideation, or distressing mental health problems.

There are several reasons why LGBTQ+ individuals may avoid care. A major one is the fear of having their gender-diverse or sexual minority identity pathologized. The outdated view that being transgender or homosexual is something “wrong” still lingers in some spaces. Until recently, homosexuality was classified as a disorder in the DSM, and gender dysphoria remains in the current edition, largely for insurance purposes. Despite this, many still fear going into a hospital or therapy setting and being treated as though something is inherently wrong with them.

There are also more direct concerns, such as discrimination by healthcare providers. This discrimination doesn’t always manifest overtly; it can come in the form of microaggressions or comments rooted in heteronormative or cisnormative beliefs. Finally, past negative experiences with healthcare providers can deter people from seeking care. If a doctor made them uncomfortable when they disclosed their sexual orientation, it can discourage them from returning to that space—or to any medical provider. It’s common for clients to ask for lists of LGBTQ+-affirming providers, emphasizing their need to feel understood and cared for in the same way as cisgender and heterosexual individuals.

LGBTQ+ Health Disparities

Minority Stress Theory has sparked extensive research into why LGBTQ+ individuals face significant health disparities. Several large studies have shed light on these disparities. For example, the All of Us research project found that LGBTQ+ adults are more likely to experience tobacco use disorder than their heterosexual and cisgender counterparts. This pattern extends to other substances as well, with research showing elevated rates of alcohol and substance use among queer and trans people. The link between stress and tobacco use, in particular, highlights how these disparities may reflect the increased stress faced by these populations.

On a more positive note, a study by The Trevor Project found that higher levels of social support are associated with fewer suicide attempts among LGBTQ+ youth. This finding reminds us that social support—whether from family, friends, or school—can be protective against suicidality.

However, challenges remain. One in four transgender adults reported experiencing an issue with their insurance related to being transgender in the past year. As my previous work in the Gender Health Department with Kaiser Permanente illustrated, insurance coverage for gender-affirming care remains a significant barrier. While there’s a perception that greater visibility for trans issues means more equality, this is not always the case.

A Myriad of Presenting Issues

In therapy, queer and trans individuals often present with many of the same issues as other clients: depression, anxiety, social isolation, and marginalization. While these issues can affect anyone, the factors behind them—such as rejection by family or the broader community—can look different for LGBTQ+ individuals.

Family conflict, for example, is common across the board but may stem from lack of acceptance of a client’s identity. For clinicians experienced in addressing family conflict, those skills are just as valuable when working with LGBTQ+ clients. Similarly, issues like substance abuse and addiction are prominent among certain LGBTQ+ subcommunities, and licensed addiction specialists can bring their expertise to this work.

More severe concerns, such as complex trauma or physical and sexual violence, are also common. Transgender individuals, especially trans women of color, are often targets of violence due to prejudice and political discourse around their identities. While trauma can affect anyone, the targeted nature of violence against transgender people is a stark reality.

Finally, LGBTQ+ individuals may present with psychosis, though there’s no unique connection between this condition and their identity. Like all clients, they may face psychosis for a variety of reasons.

Other Unique Issues

There are some unique issues to consider when working with LGBTQ+ individuals. One common issue I’ve encountered is the questioning of identity. Someone may come to therapy without identifying under the LGBTQ+ umbrella, but they’re trying to figure out, “What does this mean for me? Am I gay? Am I transgender? Am I non-binary or sexually fluid?” You’ll hear all sorts of terms in these situations, and it can be a very confusing journey for the client. This is where psychoeducation around language, gender, sexual orientation, and birth sex can be incredibly valuable in helping clients clarify these questions.

Coming out, or informing others about one’s sexual orientation or gender identity, is a unique issue within the LGBTQ+ community. While not entirely exclusive to this group—people may “come out” regarding political ideologies or religious beliefs—coming out as LGBTQ+ often brings its own set of challenges. Even someone who feels secure in their identity might face difficulties when entering new spaces, especially if they haven’t had to come out in a while. The process of coming out is ongoing, as long as we are meeting new people, and the environment can impact whether it feels safe to do so.

Gender dysphoria is another major issue for individuals exploring their gender identity. This disconnect between one’s gender identity and their sex assigned at birth, or societal expectations based on appearance, can manifest as discomfort with secondary sex characteristics, pronouns, or even the name being used for them. Gender dysphoria is complex, and working through it often requires additional training and supervision to ensure you’re guiding clients in a helpful, non-harmful way.

Internalized homophobia and transphobia, as mentioned earlier, can also be deeply challenging in therapy. Some clients may not even recognize that they are acting out this internalized negativity toward their own identity.

Pointed discrimination—whether in medical, educational, or workplace settings—can be another major issue. LGBTQ+ individuals may face systemic or interpersonal discrimination that others do not. Acknowledging these struggles helps clients feel seen and validated in their day-to-day challenges.

A particularly unique issue is the why behind identity. When there’s shame associated with a minority identity, people often ask themselves, “Why me? Why do I feel different from my heterosexual siblings? How did I end up like this?” While research continues to explore the predictors of LGBTQ+ identity, there’s still much uncertainty. Holding space for this uncertainty, especially when clients are grappling with shame, can be an important part of the therapeutic process. Acceptance can play a key role in this work.

Even for Clinicians, Issues Arise!

Even for us as clinicians, issues can arise in therapy. One common issue discussed in supervisory meetings is identity disclosure by the therapist. There are strong arguments on both sides of this, and it can depend on your therapeutic orientation, setting, and personal beliefs about how a therapist should show up in the room. There is no definitive answer, which is why it’s helpful to acknowledge that this is a complex issue for many clinicians.

This includes whether to disclose your sexual orientation, gender identity, or even the pronouns you use. These days, with the push toward transparency, many clinicians include their pronouns in email signatures. This is often done to signal to prospective LGBTQ+ clients that their identities will be respected. However, some therapists believe that providing personal information could overshadow the client’s concerns or pressure them to be open about their own identity. If you’ve struggled with this, you’re not alone—it’s a topic of ongoing discourse in the field.

So What If I Make a Mistake?

What happens if you make a mistake? If you use the wrong pronouns, the wrong name, or an outdated term for someone’s sexual orientation?

The first thing to do is apologize. Acknowledge the mistake: “I’m so sorry, I didn’t use your correct pronouns.” Then, correct yourself and move on. It’s important to avoid over-apologizing, as this can shift the burden onto the client to comfort you. Even though the mistake was well-intentioned, repeated apologies can make the client feel like they need to take care of the therapist, when they’re the ones who were slighted.

It’s also important to keep updated on preferred terms, pronouns, and names, especially if you have a large caseload. Clients may experiment with different names or pronouns throughout the course of therapy, and that’s okay. Be patient with yourself—it does get easier with time. While some may feel frustrated by this fluidity, simplifying identity exploration in that way does a disservice to the complexity of the process.

If you work in a setting where medical charts or patient files are accessible to others—such as when working with adolescents—it’s important to be mindful of how you use pronouns and names. For example, if a client isn’t ready for their family to know about their identity, you may choose not to chart using the pronouns or name they use in session. The implications of when and where to use these terms are complex, but with practice and guidance, it becomes more manageable.

Case Study

All right, as we near the end, I’d like to present a case study for consideration. You’re halfway through your third session with Amos, a 16-year-old Mexican American who uses he/him pronouns, when he reveals that he’s been scratching himself deeply over the past week. When you ask why, he hesitantly admits that he’s trying to suppress “unnatural urges.” Eventually, he confides that he believes he’s developing a crush on a close male friend, but the thought terrifies him because he’s worried he might be gay. At this point, you also recall that during the intake, Amos’s mother expressed her desire to be informed if there were any safety concerns. So, my question is: How would you proceed with Amos, given what you now know about his self-harm, its potential link to his sexuality, and his mother’s request? I’m curious to hear your thoughts on possible first steps and how you might approach this.

I can imagine that you might have conflicting thoughts about how to handle this situation. Some of you might think, “I would consult my supervisor to talk this through before proceeding.” That’s completely understandable, as it’s not always easy to give an immediate response in cases like this.

I’ll give you a moment to think about it and share your approach if you have something in mind. Broadly speaking, I think the key here is to prioritize ethical and clinical considerations, focusing on protecting our clients from harm while providing the best possible care.

I don’t intend to provide a clear-cut answer because there isn’t one. How you approach this could vary depending on the nuances of the situation. For example, you might consider whether there’s a way to address the mother’s concerns without outing Amos or jeopardizing his trust. When working with teens, we often enter gray areas regarding confidentiality. Although Amos is 16, and his parents could access his charts in most states, navigating this ethically while maintaining the therapeutic relationship is critical.

This is a common ethical dilemma, particularly when working with younger clients. It requires careful thought—sometimes what seems like the obvious answer, such as disclosing everything to the parent, may not be the best approach. There are many ways this could play out, and each has its own set of considerations.

Limitations

Now, let’s consider some limitations when working with LGBTQ+ clients. It’s important to remember that queer and trans identities are not monolithic. No two LGBTQ+ individuals are the same, just as no two straight or cisgender individuals are the same. So, even if you’ve worked with a trans client before, it doesn’t mean the next trans client will share the same experiences. There may be overlap, but each person’s story is unique, and we must approach them as such. As cultural climates shift, so do language norms. It’s essential to stay current with the language your clients use to describe themselves and their identities. Additionally, it’s crucial to consider intersecting identities before making assumptions. For example, a queer person of color may have different experiences than a white queer person. These intersections play a vital role in shaping the client’s experiences and how they present in therapy.

Finally, it’s worth noting that there are still no major federal efforts to gather comprehensive national data on LGBTQ+ experiences. This is a significant limitation in understanding the full scope of these communities. As data collection evolves, hopefully, we will have more accurate and refined insights into LGBTQ+ populations in the future.

Summary

In summary, we are ethically bound to be competent in serving clients from all backgrounds, including LGBTQ+ individuals. These populations face unique social stressors that contribute to the health and wellness issues often highlighted in research. While LGBTQ+ clients may present with similar issues as cisgender and heterosexual clients, we must remain aware of the unique challenges they face. Lastly, when ruptures occur with LGBTQ+ clients, it’s most effective to apologize, correct the mistake, and move forward.

References

American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. https://www.apa.org/ethics/code

American Counseling Association. (2014). Code of ethics. https://www.counseling.org/resources/aca-code-of-ethics.pdf

Clay, R. A. (2015, April). Competence vs. conscience: ‘Conscience clause’ initiatives expand beyond psychology training into the practice arena. Monitor on Psychology. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2015/04/competence

Drescher, J., & Fadus, M. (2020). Issues arising in psychotherapy with lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients. FOCUS, 18(3), 262–267. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.20200001

Flores, A. R., & Conron, K. J. (2023). Adult LGBT population in the United States. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/LGBT-Adult-US-Pop-Dec-2023.pdf

Hailes, H. P., Ceccolini, C. J., Gutowski, E., & Liang, B. (2020). Ethical guidelines for social justice in psychology. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 2(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000291

James, S. E., Herman, J. L., Rankin, S., Keisling, M., Mottet, L., & Anafi, M. (2016). The report of the 2015 U.S. transgender survey. National Center for Transgender Equality. https://doi.org/10.1038/064604a0

Leitch, J., & McGeough, B. L. (2023). A proposed stage model of LGBTQ people’s selection of and engagement with therapists. Families in Society, 104(3), 372–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/10443894221150667

McLemore, K. A. (2018). A minority stress perspective on transgender individuals’ experiences with misgendering. Stigma and Health, 3(1), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000070

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

Meyer, I. H. (2010). Identity, stress, and resilience in lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals of color. The Counseling Psychologist, 38(3), 442–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000009351601

Tran, N. K., Lunn, M. R., Schulkey, C. E., Tesfaye, S., Nambiar, S., Chatterjee, S., Kozlowski, D., Lozano, P., Randal, F. T., Mo, Y., Qi, S., Hundertmark, E., Eastburn, C., Pho, A. T., Dastur, Z., Lubensky, M. E., Flentje, A., & Obedin-Maliver, J. (2023). Prevalence of 12 common health conditions in sexual and gender minority participants in the All of Us research program. JAMA Network Open, 6(7), e2324969. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.24969

The Trevor Project. (2022). 2022 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health. https://www.thetrevorproject.org/survey-2022/

Additional Current References

Please Note: The following resources have been included for members to view additional resources associated with this topic area. These resources were not used by the presenter when creating this course.

Chu, T. L. (A.), Treacy, A., Moore, E. W. G., Petrie, T. A., Albert, E., & Zhang, T. (2024). Intersectionality matters: Gender, race/ethnicity, and sport level differentiate perceived coach-created motivational climates and psychological needs. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 13(1), 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000331

Dorrell, K. D., Benjamin, I., Dyar, C., Davila, J., & Feinstein, B. A. (2024). Minority stress and relationship satisfaction among bi+ individuals: The roles of partner gender and sexual orientation. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000711

Jeon, M. E., Udupa, N. S., Potter, M. R., Robison, M., Robertson, L., Rogers, M. L., & Joiner, T. E. (2024). Measurement invariance of the Depressive Symptom Inventory–Suicidality Scale across race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and plurality of minoritized identities. Psychological Assessment. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0001306

Kim, H. J., Romanelli, M., & Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. (2024). Multidimensional social connectedness of sexual and gender minority midlife and older adults: Findings from the National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study (NHAS). American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000726

Lloyd, A., Granot, Y., Rovegno, E., Bazin, A., Bryant, A., & Richards, M. (2024). How schools can bolster belonging among Black lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer youth. Translational Issues in Psychological Science. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000039

Citation

Arriaga, A. (2024). Providing behavioral health treatment to LGBTQ+ populations: Introductory ethical and clinical considerations. Continued.com, Article 76. Available at www.continued.com/psychology