Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Working with Transgender and Gender Diverse Youth: Navigating the Current Political Climate, Clinical Practice Guidelines, and Ethical Considerations, presented by Giselle Levin, PsyD.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Describe current mental health challenges facing transgender and gender-diverse youth.

- Identify standards and clinical practice guidelines for provision of gender-affirming care of youth.

- Apply clinical interventions to support transgender and gender-diverse youth coping with minority stress and other mental health challenges.

Limitations/Risks

- This presentation presents the fundamentals of working with trans and gender-diverse youth. Further training, supervision, and/or consultation may be required before working with specific patients.

- Information in the presentation is generalized and may not apply to specific patients. Refer or consult as needed.

- Ethical and legal standards may differ from state to state. Ensure that you are familiar with the laws and ethics specific to your state.

- Individual and cultural considerations should be explored prior to pursuing treatment and interventions.

Introduction

Today, we will explore how mental health professionals like you can support transgender and gender-diverse youth and their families in your practice. We will focus on the impact of minority stress, discussing its significance and associated mental health challenges. As a fundamental course, we'll introduce the standards of care, though we will not delve deeply into complex topics.

Assessing gender-diverse youth for readiness to begin puberty blockers, hormones, or surgeries requires a nuanced approach. Such medical gender-affirming care demands additional training, supervision, and consultation. You may encounter patients with complex needs that necessitate specialized attention. In these cases, always refer or consult based on your training level and comfort with the patient's specific situation.

We'll also cover some general information useful when dealing with particular cases. Understanding ethical and legal standards is crucial, which vary significantly from state to state. I will show a detailed map highlighting the various pieces of legislation proposed and passed across different states. Being aware of the laws in your state is essential, as is understanding the ethical codes specific to your professional field. For instance, as a psychologist, my guidelines might differ from those for Licensed Marriage and Family Therapists (LMFTs) or social workers. Lastly, we must consider individual and cultural factors before pursuing treatment or interventions. These preliminary considerations are vital in providing effective and sensitive care to your patients.

The Political Climate: Events, Legislation, and Articles

Let's examine the current political climate, focusing on recent events, legislation, and related articles. We'll start with anti-transgender bills in 2024. Remarkably, even though it's only April of 2024, there have already been 539 bills proposed across 41 states this year. This widespread legislative activity has affected nearly every state in the U.S. Of these bills, 21 have passed, 92 have failed, and the majority, 426, remain active. This volume of legislation underscores the significant attention and contention surrounding this issue.

What exactly do these bills entail? These bills target:

- Re-definition of sex

- Curriculum censorship

- School facilities bans (bathrooms, lockers)

- School sports bans

- Forced outing in schools

The redefinition of sex often stipulates sex as strictly binary—male or female—and identical to the sex assigned at birth. This conflation of sex and gender precludes any later changes in gender identity if it doesn't match the sex assigned at birth.

Another significant area is curriculum censorship. This includes bills that prevent discussions about LGBTQ+ individuals, particularly transgender and gender-diverse topics, within schools. It restricts teachers from using books with non-binary or transgender characters and limits educational resources and opportunities. Such bills also aim to censor or ban LGBTQ+ groups in schools and impose facility bans that restrict students from accessing certain facilities, like bathrooms, that do not align with their gender assigned at birth.

For example, a transgender girl who fully presents as female would be compelled to use the boys’ bathroom or locker room. School sports bans are also prevalent, prohibiting transgender students from joining teams that align with their gender identity rather than their assigned sex at birth.

Forced outing is another concerning issue. This practice requires that transgender students be outed at school, making their transgender status known to teachers and peers, which can lead to bullying and create a hostile environment.

Healthcare restrictions are also widespread. These include age limits on accessing gender-affirming care and could even carry criminal penalties for providers who offer such care to transgender youth. Interestingly, these restrictions often exempt similar treatments for cisgender youth or mandatory treatments for intersex infants.

Speaking of intersex individuals—those whose biological characteristics do not fit typical binary notions of male or female bodies—it’s estimated that approximately 1.7% of the population is intersex. This might involve chromosomal differences or ambiguous genitalia. Many intersex infants undergo surgery without their consent, yet such procedures are generally not subject to the same restrictions as gender-affirming surgeries for older youth.

Additionally, there are prison restrictions that disproportionately affect transgender individuals in incarceration, often denying them access to essential gender-affirming treatments. Funding restrictions also play a role, blocking programs like Medicaid from covering necessary treatments for transgender individuals.

Religious exemptions are another barrier, allowing healthcare providers and others in the community to deny care or services to LGBTQ+ individuals based on religious beliefs. Lastly, there are significant hurdles regarding accurate IDs. Restrictive bills limit the ability to update gender information on official documents like birth certificates and driver's licenses, which can lead to discrimination and violence, as well as practical challenges in employment, housing, and travel.

In addition to the types of bills previously discussed, there are other anti-LGBTQ+ legislative actions that don't necessarily fit neatly into those categories. These include bans on marriage equality and bills that preempt or override local non-discrimination protections, stripping back established rights and safeguards for LGBTQ+ individuals.

Bills Passed in 2024

AL SB129: “Each public institution of higher education shall ensure that every multiple occupancy restroom be designated for use by individuals based on their biological sex.”

In higher education, policies now mandate that individuals use restrooms based on their biological sex, not their gender, gender identity, or presentation. This requirement overlooks the complexities of gender expression and identity.

ID H0421: “In human beings, there are two, and only two, sexes: male and female; (2) Every individual is either male or female; (3) An individual's sex can be observed or clinically verified at or before birth”

This is scientifically incorrect. As previously mentioned, an estimated 1.7% of people are intersex, meaning they possess sex traits that do not conform to the traditional binary. For example, someone with androgen insensitivity syndrome, a common intersex condition, is genetically male with XY chromosomes but is resistant to male hormones like testosterone. Consequently, they do not develop male characteristics and typically appear female at birth, often being designated as female despite lacking internal female reproductive organs and being infertile.

Another intersex condition, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, occurs in individuals with XX chromosomes who produce high levels of androgens. This can lead to ambiguous genitalia, where external genitalia may appear male, yet internal genitalia include a uterus. Therefore, the sex of someone with congenital adrenal hyperplasia cannot be definitively observed or clinically verified at birth.

These examples illustrate that such legislation is not grounded in science and is, in fact, scientifically inaccurate. It can be especially harmful not only to transgender individuals but also to those who are intersex.

WI AB377: “The three designations are 1) males, 2) females, and 3) males and females. The bill defines “sex” as the sex determined at birth by a physician and reflected on the birth certificate. The bill also requires an educational institution to prohibit a male pupil from participating on an athletic team or in an athletic sport designated for females. Finally, the bill requires the educational institution to notify pupils and parents if an educational institution intends to change a designation for an athletic team or sport.” VETOED

This bill was vetoed, but it aimed to define sex strictly as male and female, the only designations deemed valid, a scientifically incorrect concept. Additionally, it stipulated that these designations be determined at birth. Under this bill, a male pupil—including a transgender girl—would not be allowed to participate on an athletic team or in a sport designated for females. Furthermore, the bill mandated that educational institutions notify students and parents if a transgender child was to join a sports team that aligned with their gender identity.

ID H0455: “Requiring students to share restrooms and changing facilities with members of the opposite biological sex generates potential embarrassment, shame, and psychological injury to students, as well as increasing the likelihood of sexual assault, molestation, rape, voyeurism, and exhibitionism; every public school restroom or changing facility accessible by multiple persons at the same time must be: (a) Designated for use by male persons only or female persons only; and (b) Used only by members of that sex.”

You can see that many of these rules deeply affect students, which is particularly concerning given that schools are already challenging environments for youth. Under these regulations, students would not be able to use restrooms that align with their gender identity. Interestingly, the rationale provided states that allowing students to share restrooms and changing facilities could lead to potential embarrassment, shame, and psychological injury. However, this concern appears to focus solely on cisgender students. The statement further suggests that this mixing increases the likelihood of sexual assault, molestation, rape, voyeurism, and exhibitionism.

Yet, there is no research supporting the claim that transgender individuals using bathrooms that align with their gender identity are more likely to perpetrate any form of sexual misconduct in those settings. Thus, these assertions are not backed by empirical evidence. Moreover, the policy mandates that public school restrooms and changing facilities, like locker rooms, be designated strictly for male or female use based on the sex assigned at birth.

WY SF0099: “No physician or health care provider shall: [...] Provide, administer, prescribe or dispense [...] prescription drugs that induce [...] puberty suppression or blocking prescription drugs to stop or delay normal puberty; [...] Supraphysiologic doses of testosterone to females [...] Supraphysiologic doses of estrogen to males.”

Here, we examine another bill that was passed, which prohibits physicians and healthcare providers from offering medical gender-affirming care to youth. This includes prescribing or dispensing drugs that induce, block, or delay puberty.

We'll discuss puberty blockers in more detail shortly. These medications are completely reversible and provide transgender youth with additional time to explore their gender identity and consider their options before making any irreversible decisions. Importantly, puberty blockers also spare them from undergoing puberty, which might be dysphoric and distressing. Once these blockers are discontinued, the individual will experience their natural puberty.

The bill also addresses testosterone and estrogen, which are used in hormone therapy. We will delve into the distinctions between puberty blockers and hormone therapy later. While the effects of hormone therapy are partially reversible, some aspects are irreversible. This bill bans both treatments, impacting the ability of transgender youth to receive care that could significantly ease their gender dysphoria.

ID S1352: “No person engaged in the practice of professional counseling or marriage and family therapy in the state of Idaho shall be required to provide counseling to or facilitate the counseling of a client in support of goals, outcomes, or behaviors that conflict with the sincerely held religious, moral, or ethical principles of the counselor or therapist.”

We're seeing that therapists who do not support transgender youth are not required to provide services, which, in a way, aligns with ethical obligations to refer patients when there is significant negative bias. Ethically, it is crucial that patients are treated by professionals who can support them without prejudice.

However, the situation is nuanced. While it is understandable that a transgender youth would not benefit from working with a therapist who harbors strong anti-trans sentiments, the legislation also allows therapists to refuse to facilitate counseling that supports the client's goals if these goals conflict with the therapist's moral principles. This aspect of the law can lead to a lack of support for transgender youth, as it permits professionals to decline to provide essential therapeutic services based on personal beliefs, potentially leaving vulnerable clients without necessary care.

I must emphasize that the ramifications of these bills extend beyond transgender individuals, affecting cisgender people as well. This is particularly evident in policies like bathroom bans or facility restrictions.

Consider, for instance, the impact on intersex individuals, who make up an estimated 1.7% of the population and do not fit neatly into the binary categories of male or female. They are directly affected by such legislation. But the implications also reach cisgender individuals. For example, women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), a condition that can cause facial hair growth, may face discrimination in female restrooms despite being cisgender.

Moreover, societal assumptions about gender appearance can lead to accusations and challenges for cisgender individuals as well. Online and in public spaces, cisgender women and men are sometimes mistakenly identified as transgender, leading to harassment and discrimination. This can occur even with individuals who exhibit traditionally feminine or masculine traits—demonstrating that appearance alone is not a reliable indicator of someone's gender identity.

These legislative measures also affect children and youth, who may be subjected to similar forms of discrimination and misunderstanding. The scope of harm from such bills is wide, impacting not only those who are transgender but also many who are not, including those with certain medical conditions and the broader cisgender population.

Tracking Anti-Trans Legislation

If you're interested in staying informed about anti-trans legislation, several excellent resources are available. "Erin In The Morning" offers a comprehensive Anti-Trans Legislative Risk Assessment Map, which details the status of proposed and passed bills in each state. This map is particularly useful for understanding the legislative risks and includes separate sections for adults and youth. Initially, much of this legislation targeted youth, but there is now also a significant amount aimed at adults.

Additionally, the ACLU is tracking 484 anti-LGBT bills. Their website provides updates on their progress, whether they have just been proposed or have already been passed. It’s a valuable resource for those looking to understand the broader scope of legislation affecting the LGBTQ+ community.

There is also a trans legislation tracker available online. This tool is specifically designed to follow legislation that directly impacts transgender individuals. Using these resources can provide a clearer picture of the legislative landscape and help you stay informed about changes that might affect your community.

In The News

Recently, there has been a noticeable increase in media coverage concerning gender-affirming care, particularly for youth. A prominent New York Times article raised concerns about the adequacy of mental health assessments for youth receiving such care. It suggested that co-occurring mental health issues were not adequately addressed, leading some individuals to ultimately detransition or express regret.

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), a key global organization in transgender healthcare similar to the American Psychological Association (APA), provides evidence-based standards of care. WPATH's latest manual, the Standards of Care 8, is accessible online at no cost and extensively cites the supporting research. WPATH also maintains a confidential forum for medical and mental health experts to discuss complex cases. Unfortunately, this forum was recently compromised by anti-trans activists, resulting in the unauthorized release and misrepresentation of confidential information in what became known as the "WPATH Files."

Erin In The Morning responded with a detailed rebuttal, highlighting the misinterpretations and distortions of the leaked information, which seemed designed to fuel anti-trans rhetoric. This incident is just one example of the challenges facing medical and mental health providers working with transgender individuals, particularly youth. There have been cases of individuals posing as patients to expose providers, a form of healthcare fraud that adds to the already tense environment.

There are numerous anti-trans articles circulating. We'll discuss further how this affects transgender youth and explore ways you, as a provider, can take a supportive stance. It's crucial to understand that transgender healthcare, particularly for trans youth, is currently at the center of intense political controversy. This group has been singled out as a focal point for debate and conflict. Consequently, there is a significant amount of anti-trans rhetoric specifically targeting this vulnerable population. As healthcare providers, recognizing this context is essential for effectively supporting and advocating for transgender youth.

Trans and Gender-Diverse (TGD) Youth

Let's shift our focus to understanding trans and gender-diverse youth. First, it's important to clarify terminology. We often use the terms "trans and gender-diverse" or "trans and gender-expansive" because not all youth under this umbrella identify strictly as transgender. Additionally, some children who identify as gender-diverse in their youth may not retain these identities into adulthood. Gender diversity can be fluid and subject to change, which we'll explore further.

To provide some context on the broader spectrum of LGBT identification, let’s consider recent data. According to a Gallup Poll, which has been tracking LGBT identification since 2012, with the latest poll conducted in 2024, there are notable generational differences in how people identify. Among Boomers, only 5% identify as part of the LGBT community, compared to 10% of Millennials and a significant 25% of Gen Z—reflecting a substantial generational shift.

Specifically focusing on transgender identification, the numbers are smaller but still indicative of a generational change: 0.2% of Boomers, 1.1% of Millennials, and 2.8% of Gen Z identify as transgender. Most of the LGBT Gen Zers are bisexual, with about 15% identifying as such, which is a stark contrast to those identifying as gay or lesbian. Other identities within the LGBT spectrum, including transgender, represent smaller percentages but are crucial for understanding the full diversity within these communities.

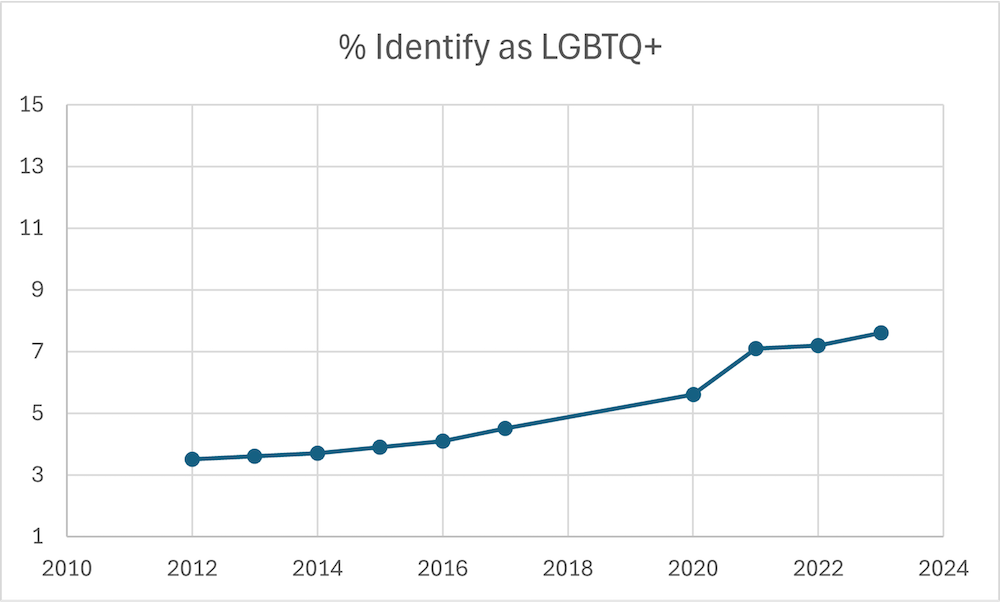

Figure 1. Graph showing the percentage of people identifying as LGBTQ+.

Since the initiation of the Gallup Poll in 2012, which tracks LGBT identification among those aged 18 and older, there has been a noticeable increase in the percentage of individuals identifying as LGBT. Figure 1 provides a visual display of this information. In 2012, approximately 3.5% of the population identified as LGBT, a figure that rose to 5.6% four years ago and stands at 7.6% today. This significant increase suggests a changing landscape in societal acceptance and self-recognition of diverse sexual orientations and gender identities.

The rise in LGBT identification, particularly among Gen Z, where a large portion identifies as bisexual, may reflect greater societal acceptance and visibility. Older generations, like Boomers, who identify as LGBT are more likely to describe themselves as lesbian or gay, which may indicate a previous era's more restrictive understanding of sexuality. The broader acceptance of bisexuality today suggests that individuals who might not have previously explored or accepted this aspect of their identity now feel more comfortable doing so.

Moreover, the acceptance of non-binary identities within the transgender community has also grown. Historically, societal acceptance was generally extended only to those who presented themselves fully as either female or male—transgender women or men. There is increasing recognition and support for individuals who identify outside these binary categories, acknowledging those who feel they lie somewhere in the middle, embody elements of both, or do not fit into the binary at all. This shift is critical in understanding the increase in individuals identifying as transgender or non-binary.

Gender Diversity in Children

Gender diversity in children is a normal aspect of developmental progression. From as early as two or three years old, children begin to recognize and interact with the concept of gender, understanding its social elements. In preschool, it's common to see children gravitating toward certain toys or clothing traditionally associated with a particular gender—boys opting for dolls or wearing tutus and girls preferring boys' attire and rejecting the color pink.

It's crucial to recognize that such expressions of gender diversity in young children are not indicative of a pathological condition. Nor do they necessarily predict a future transgender identity or gender incongruence. For example, a boy who enjoys wearing tutus might grow up to identify as a man, possibly as a more feminine man or as a gay man, reflecting variations in sexual orientation rather than gender identity. Similarly, femininity in cisgender gay men or masculinity in straight women are expressions of gender diversity that don't strictly align with transgender or non-binary identities.

Gender expression in children is fluid and cannot reliably predict future gender identity. A child showing gender-diverse traits may grow up to identify within a range of possibilities—from continuing to embrace a gender-diverse identity, to identifying as a feminine man or masculine woman, or not aligning with any of these categories permanently. Essentially, there is no fixed path or clear predictor for how a child's gender identity will evolve.

Understanding this fluidity is vital in supporting gender-diverse children. We recognize gender diversity not as an anomaly but as a part of the broader spectrum of human development that occurs naturally alongside the emergence of gender awareness in children. This perspective is fundamental when discussing what gender diversity means for children and how to support their growth in a nurturing and affirming environment.

Gender Diversity in Adolescence

Gender diversity in adolescence presents unique considerations. In discussions about adolescence, including those within WPATH (World Professional Association for Transgender Health), we typically consider this period as extending from puberty to the age of maturity. However, the exact parameters of adolescence aren't strictly defined, as puberty can start very early in some children, and cognitive development, particularly executive control neural systems, continues into the mid-twenties. This development challenges the notion that turning 18 automatically signifies the transition from adolescence to adulthood, as cognitive development continues well past this age.

In the United States, the age of majority is 18, but it's important to recognize that this age can range from 15 to 21 in other countries. Moreover, turning 18 doesn't necessarily equate with immediate independence or adult responsibilities. Many individuals continue to depend on their parents well into their mid-twenties, which is why considerations relevant to adolescents often apply to transitional-age youth—those from the age of majority up to about 25. These young adults are navigating the complex journey from adolescence to full adulthood, dealing with both social and psychosocial challenges.

Legally, the standards of care for adolescents apply up until the age of 18. After this, adult standards of care take precedence. It's also crucial to acknowledge that some adolescents may experience gender incongruence from childhood, while others only encounter these feelings during puberty—a time of significant physical and gender development that can trigger the onset of gender dysphoria or incongruence.

Regarding terminology, "dysphoria" and "incongruence" are often used interchangeably, though they represent a diagnostic distinction between DSM-5 and ICD-11 frameworks. These terms describe a mismatch between an individual's gender assigned at birth and their experienced gender.

Adolescence is a pivotal time for gender identity development, which often begins in childhood but intensifies during puberty. Influences such as social media and peer interactions play significant roles in shaping gender expectations and identities during this time. As adolescents learn and navigate these influences, their understanding of gender and identity continues to evolve, making adolescence a critical period for support and guidance in gender identity development.

A comprehensive clinical approach is crucial when working with transgender adolescents. This approach is necessary partly because adolescents must be able to understand hypothetical situations to give informed consent for treatments that might have long-term effects. Children often struggle with this concept, but adolescents are generally developing the cognitive awareness needed to think about future consequences and cause-and-effect relationships. However, it's also common for adolescents to display risk-taking behaviors and experience a sense of urgency, perceiving time differently than adults.

Those of you who have worked with teenagers, especially those in distress like depression, might notice that they have difficulty envisioning a life different from their current situation. They often feel an immediate need for change, driven by a heightened sensitivity to rewards, which focuses their attention on short-term outcomes rather than long-term implications. Additionally, adolescents place significant importance on peer relationships, which can be a source of support or a risk factor, depending on the health of those relationships. As they seek more autonomy from their parents, the influence of their peers can become even more pivotal.

The variability in maturity among teenagers is notable. For example, a 17 or 18-year-old might exhibit less self-awareness and insight than a 14-year-old. This individuality means that when making decisions about gender-affirming medical treatments—which can have lifelong consequences—it's essential to consider a range of developmental factors.

This nuanced understanding of adolescent development informs our approach to their care. In my presentations on hormone therapy or surgery for adults, the focus on these developmental considerations is less intense, reflecting adults' greater maturity and decision-making capacity. However, with adolescents, we exercise heightened diligence during the assessment process to ensure that decisions about their care are made with a full understanding of the potentially irreversible effects. This careful approach is vital in supporting adolescents as they navigate these critical decisions.

Minority Stress & Mental Health in Trans and Gender-Diverse Youth

Minority Stress Theory

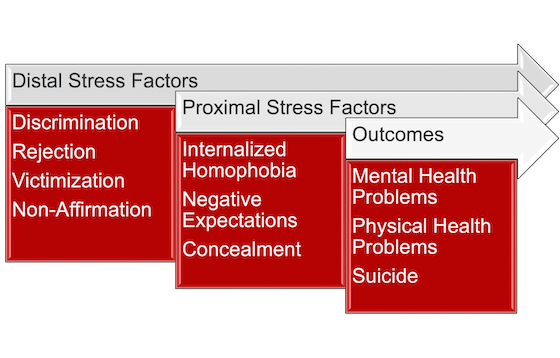

Let's delve into the topic of minority stress and its impact on the mental health of youth. Minority stress theory, developed by Meyer and seen in Figure 2, is a foundational framework for understanding the mental and physical health disparities observed in LGBT individuals, particularly transgender people.

Figure 2. Minority Stress Theory.

Research strongly supports the minority stress theory, suggesting that LGBT people face higher rates of mental and physical health issues. The question arises: Why does this disparity exist? The theory identifies two primary types of stress factors: distal and proximal.

Distal stress factors represent external stressors that significantly affect the well-being of transgender individuals. These include discrimination, rejection by family, peers, or institutions, victimization through physical or verbal abuse, and non-affirmation, such as being deliberately misgendered or called by incorrect pronouns.

The impact of these distal stress factors is profound, directly correlating with severe outcomes. They contribute to a heightened incidence of mental and physical health problems within the transgender community, particularly among transgender youth. Furthermore, these factors are strongly associated with the tragically high rates of suicide observed among transgender individuals.

The direct link between these external stressors and negative health outcomes underscores the critical need for supportive interventions and policies to mitigate these stressors and provide transgender individuals, especially youth, with safer, more affirming environments.

Proximal stress factors involve the internalization of the external stressors described as distal factors. These internal stressors include internalized homophobia or transphobia, where a transgender individual may feel there is something inherently wrong with them due to their identity, leading to feelings of shame, disgust, or severe self-criticism.

Additionally, negative expectations can heavily impact transgender individuals, especially youth. Many feel their future prospects are bleak—believing they will never succeed in personal relationships, career ambitions, or broader societal acceptance. This often results in low self-esteem and confidence, which may not always be directly linked to their gender identity in their own minds but stems from the ongoing internalization of societal rejection and stigma.

Concealment is another significant proximal stress factor. Many transgender individuals may hide their identity by engaging in activities like secretly trying on clothes that affirm their gender identity or purchasing and hiding such items to avoid detection and potential conflict. This behavior is a direct response to the fear and anxiety produced by societal judgment and lack of acceptance.

These proximal stress factors mediate the relationship between external pressures and the negative outcomes they cause, establishing a complex interaction where external abuses become internal struggles that further exacerbate health and well-being issues. This mediation illustrates how distal factors impact individuals directly and indirectly by fostering harmful internal narratives and behaviors.

Furthermore, the concept of multiple minority stress must be considered. This occurs when individuals identify with more than one marginalized group, compounding their experiences of stress and adversity. For example, a transgender person of color may face intersecting prejudices related to both their gender identity and race, intensifying their experience of minority stress and its associated impacts. Understanding and addressing these layered stresses is crucial for supporting the mental and physical health of transgender individuals, particularly those who are navigating multiple marginalized identities.

ADDRESSING Framework

The ADDRESSING framework, developed by Pamela Hayes (2008), is an essential tool for understanding the complexities of individual identity, particularly concerning marginalization, power, and privilege. This framework breaks down various categories contributing to an individual's identity, each linked to potential marginalization. Here's a brief overview of each component within the ADDRESSING acronym:

- Age: Young people and older adults often possess less societal power than adults aged 18 to 65, who typically have more influence.

- Disability (Developmental): Autism is a common example. Individuals with developmental disabilities may experience increased minority stress. Notably, there is a significant overlap between individuals who are autistic and those who are transgender, with higher incidences of autism among transgender populations and vice versa.

- Disability (Acquired): Conditions like traumatic brain injury or spinal cord injuries that occur later in life. Like developmental disabilities, these also lead to increased minority stress and can profoundly impact an individual’s life and identity.

- Religion: Religions other than Christianity often face more marginalization in predominantly Christian societies.

- Ethnicity: Ethnic minorities, or kids of color, generally experience greater marginalization compared to their white peers.

- Socioeconomic Status (SES): Individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds have less privilege than those from higher income brackets.

- Sexual Orientation: Within the transgender community, those who are heterosexual typically experience less discrimination compared to transgender individuals who are gay, lesbian, bisexual, or otherwise non-straight. For example, a transgender girl attracted to men is considered straight and may face fewer challenges than a transgender girl attracted to women or both genders. Transgender individuals who are straight have better mental health care. They have more privileges than transgender individuals who are also lesbian, gay, or bisexual.

- Indigenous Heritage: Individuals with indigenous backgrounds can face unique challenges and discrimination, adding another layer to their identity and experiences of marginalization.

- National Origin: The citizenship status of an individual, particularly when they are transgender, can significantly impact their mental health and well-being. Non-U.S. citizens, especially from countries with limited LGBT rights, face ongoing stress due to potential instability in their residency status. For example, I currently have a patient who is a transgender woman from India, sponsored by her company to work in the tech industry, which is notably volatile at the moment, especially in the Bay Area. She lives with the constant fear of losing her job, and if that were to happen, she believes she would have only about 30 to 60 days to find new employment or face deportation to India, where she would have far fewer protections.

- Gender: It's also crucial to acknowledge how gender affects experiences of privilege and marginalization. Transgender individuals and women typically have less privilege compared to cisgender men, facing numerous systemic barriers that impact their social, professional, and personal lives.

Understanding these dimensions of identity through the ADDRESSING framework helps to highlight the intersecting challenges faced by individuals, emphasizing the need for targeted support and inclusive policies to mitigate these pressures.

Impact of Minority Stress

The impact of minority stress on mental health disparities among transgender and gender-diverse youth is significantly influenced by their experiences of discrimination and rejection. Research confirms that support and acceptance from family, friends, and educational institutions play a critical role in the well-being of these youths. When their social environments embrace them, transgender and gender-diverse youth often show good psychological adjustment and resilience.

Conversely, when they lack support, the consequences can be severe. Distal stressors such as discrimination and rejection can lead to these youths feeling ostracized from their school life, exacerbating feelings of isolation. This external rejection often fosters internalized transphobia and low expectations, which can further deepen their sense of isolation and alienation.

Effective coping strategies involve proactive advocacy for inclusion, particularly within educational settings. Working directly with teachers to promote understanding and acceptance and fostering peer support networks are essential actions. Addressing the mental health needs of transgender youth thus requires a holistic approach that involves their families, peers, and schools. These elements are not just supportive aspects of their lives; they are pivotal determinants of a transgender youth's mental health outcomes.

Have You Heard the News?

The impact of anti-trans legislation is a significant source of minority stress for transgender youth and young adults, manifesting as a profound distal stress factor. A study conducted between September and November of 2021 explored the implications of exposure to news about newly proposed anti-trans legislation and how perceptions of support for this legislation within one's social network—such as from parents or friends—affect these individuals.

The findings were concerning: news consumption related to this legislation was directly associated with increased rumination and physical health symptoms among trans youth and young adults. Furthermore, if these individuals perceived that their social network supported the legislation, they experienced even greater rumination, depressive symptoms, physical health symptoms, and an intensified fear of disclosing their identity.

The study also included open-ended questions, which revealed that this legislation not only affects access to gender-affirming healthcare but also impedes their ability to seek general healthcare services. Many avoid medical settings altogether due to fear of discrimination or past negative experiences. Additionally, the legislative climate has led to an increase in discrimination during medical treatment and prompted unhealthy coping responses among these individuals. These findings highlight a crucial message for policymakers: the laws they propose and enact have real and damaging effects on the mental and physical well-being of trans youth.

Gender-Affirming Interventions for Trans and Gender-Diverse Youth

Gender-Affirming Care: Social Transition

Gender-affirming interventions for trans and gender-diverse youth are crucial for their well-being and are often misunderstood. Here’s an overview of what these interventions entail and the standards of care involved.

- Name change;

- Pronoun change;

- Change in sex/gender markers (e.g., birth certificate, identification cards, passport, school and medical documentation, etc.);

- Participation in gender-segregated programs (e.g., sports teams, recreational clubs and camps, schools, etc.);

- Bathroom and locker room use;

- Personal expression (e.g., hairstyle, clothing choice, etc.);

- Communication of affirmed gender to others (e.g., social media, classroom or school announcements, letters to extended families or social contacts, etc.). (Coleman et al., 2022)

Social transition is the primary approach for children who are prepubertal, typically younger than 10 or not yet at Tanner stage 2 of puberty. Medical interventions like hormones, puberty blockers, or surgeries are not considered for children who have not reached these developmental milestones. Social transition involves several reversible changes designed to affirm a child's experienced gender. This includes updating their name across various settings to reflect their gender identity, adopting pronouns that align with the child’s gender identity, and changing gender markers on official documents such as birth certificates, school records, and medical documents to reflect the child's affirmed gender. Children are also allowed to participate in activities and programs, such as sports teams, that align with their gender identity.

For prepubertal children, hormonal differences are not yet a factor, which supports their inclusion based on their affirmed gender rather than their sex assigned at birth. Facilitating access to bathrooms and locker rooms that correspond with the child’s gender identity is another aspect of social transition. Supporting the child in expressing themselves through clothing, hairstyle, and other forms of personal presentation that reflect their identity is also key. Additionally, helping to communicate the child’s gender identity to others, which might include social media announcements or letters to extended family members, is part of this process.

These elements of social transition are entirely non-medical and reversible. They are aimed at supporting the child in a way that affirms their identity, which is critical for their psychological and emotional health.

Gender-Affirming Care: Prosthetics

In addition to social transition, other non-medical, gender-affirming interventions involve prosthetics or specific training to help individuals express their gender identity. These interventions, which do not involve medication or surgery, play a crucial role in aligning one’s external appearance with one's gender identity.

For masculinizing purposes, binders are often used. These compression garments are designed to flatten the chest, creating a more masculine appearance, and are suitable for individuals who have experienced breast development but are not seeking medical treatment. Packers, another form of prosthetic, are utilized to create the appearance of a bulge in the genital area, simulating the presence of a penis. STP (stand-to-pee) devices enable individuals who do not have a penis to urinate while standing. These devices are shaped to function as prosthetics and urinary aids.

For feminizing effects, gaffs and tucking are common practices. Tucking involves repositioning the penis and testicles to achieve a smoother appearance in tight clothing, while gaffs are specialized undergarments designed to hold these parts securely. Breast forms, worn to simulate the appearance of breasts, enhance the feminine silhouette. Wigs also play an essential role, particularly for individuals who desire longer hair or face challenges with hair loss.

Additionally, aesthetic procedures like laser hair removal aid in achieving a more consistent appearance with one’s gender identity, though their reversibility varies. Voice training is another critical aspect, helping individuals modify their vocal pitch and resonance to better match their gender presentation. While some may seek professional guidance for voice training, others might use self-guided methods.

These gender-affirming interventions, while non-medical, are vital components of the support system for transgender and gender-diverse individuals, offering additional ways to safely and comfortably express their identities.

Gender-Affirming Care

The final piece of gender-affirming care involves medical transition, which consists of three primary categories. The first category includes puberty blockers, also known as GnRH analogs. These blockers prevent the development of endogenous secondary sex characteristics, effectively pausing puberty. This intervention is fully reversible, with no impact on fertility or other puberty-related changes once the treatment is discontinued. Puberty blockers provide adolescents with additional time to explore their gender identity without the distress often associated with puberty. For instance, a 12-year-old at Tanner stage 2 might use puberty blockers to halt puberty, allowing time for further cognitive development and exploration before making decisions about hormones, which are only partially reversible.

Tanner stage 2 marks the onset of visible changes. For those designated female at birth, this stage typically starts between ages 9 and 11 and is characterized by the development of breast buds under the nipples, which may become itchy or tender. The areola, the darker area around the nipple, expands, and the uterus begins to grow. A small amount of pubic hair starts to appear. Tanner stage 2 generally begins around age 11 for those designated male at birth. Changes include enlargement of the testicles and the scrotum, with some pubic hair forming at the base of the penis. It is at this stage that puberty blockers are deemed appropriate, not earlier.

The second category of medical transition involves hormones. For individuals assigned male at birth, the regimen can include estrogen and testosterone blockers, while those assigned female at birth may receive testosterone. The effects of hormone therapy are partially reversible. For example, breast growth induced by estrogen does not recede when hormone treatment is stopped and would require surgical removal if desired. Prolonged hormone use can also impact fertility. Testosterone administration can lead to irreversible changes such as voice deepening and facial and body hair growth. Hair loss, another effect of testosterone, is also irreversible. Fertility effects are generally more reversible for those assigned female at birth taking testosterone compared to those assigned male at birth on estrogen and testosterone blockers.

The third category is surgeries, which are entirely irreversible. While reconstructive surgeries are possible, they do not fully reverse the original alterations. Masculinizing top surgery, or double mastectomy, is the most common procedure performed under age 18, typically starting at age 16. This procedure achieves a flatter chest appearance. Most other surgeries are recommended after age 18.

WPATH Standards of Care 8: Children

Continuing with the Standards of Care 8, we focus now on children, particularly those who are pre-puberty. It is crucial to emphasize that the standards of care do not involve any medical interventions for these children. Instead, the focus is on providing support through knowledge and understanding.

- 7.1 - We recommend health care professionals working with gender-diverse children receive training and have expertise in gender development and gender diversity in children and possess a general knowledge of gender diversity across the life span.

- 7.2 - We recommend health care professionals working with gender-diverse children receive theoretical and evidenced-based training and develop expertise in general child and family mental health across the developmental spectrum.

- 7.3 - We recommend health care professionals working with gender-diverse children receive training and develop expertise in autism spectrum disorders and other neurodiversity or collaborate with an expert with relevant expertise when working with autistic/neurodivergent, gender-diverse children

- 7.4 - We recommend health care professionals working with gender-diverse children engage in continuing education related to gender-diverse children and families.

- 7.5 - We recommend health care professionals conducting an assessment with gender-diverse children access and integrate information from multiple sources as part of the assessment.

- 7.6 - We recommend health care professionals conducting an assessment with gender-diverse children consider relevant developmental factors, neurocognitive functioning, and language skills.

- 7.7 - We recommend health care professionals conducting an assessment with gender-diverse children consider factors that may constrain accurate reporting of gender identity/gender expression by the child and/or family/caregiver(s).

- 7.8 - We recommend health care professionals consider consultation, psychotherapy, or both for a gender-diverse child and family/ caregivers when families and health care professionals believe this would benefit the well-being and development of a child and/or family.

- 7.9 - We recommend health care professionals offering consultation, psychotherapy, or both to gender-diverse children and families/caregivers work with other settings and individuals important to the child to promote the child's resilience and emotional well-being.

- 7.10 - We recommend health care professionals offering consultation, psychotherapy, or both to gender-diverse children and families/caregivers provide both parties with age-appropriate psychoeducation about gender development.

- 7.11 - We recommend that health care professionals provide information to gender-diverse children and their families/caregivers as the child approaches puberty about potential gender-affirming medical interventions, the effects of these treatments on future fertility, and options for fertility preservation.

- 7.12 - We recommend parents/caregivers and health care professionals respond supportively to children who desire to be acknowledged as the gender that matches their internal sense of gender identity.

- 7.13 - We recommend health care professionals and parents/caregivers support children to continue to explore their gender throughout the pre-pubescent years, regardless of social transition.

- 7.14 - We recommend the health care professionals discuss the potential benefits and risks of a social transition with families who are considering it.

- 7.15 - We suggest health care professionals consider working collaboratively with other professionals and organizations to promote the well-being of gender-diverse children and minimize the adversities they may face.

Healthcare professionals working with gender-diverse children must be well-trained in gender diversity across the lifespan. This training should also encompass general child and family mental health and expertise in working with neurodiverse conditions such as autism spectrum disorders and ADHD. For those without direct training in these areas, collaboration with experts who possess this knowledge is essential. This is particularly important given the noted overlap between transgender identities and autism; many autistic children are trans, and vice versa, though the reasons for this correlation are not fully understood and continue to be a subject of research.

The diagnostic criteria for autism, primarily based on studies of cisgender boys, may not accurately reflect the experiences of cisgender girls or transgender children. Recent research indicates that the manifestation of autism characteristics can differ significantly in these groups compared to the established DSM-5 criteria. This highlights the necessity for ongoing education and adaptation of diagnostic approaches to better serve a diverse population.

WPATH also emphasizes the importance of continuous professional development. Healthcare providers are encouraged to pursue continuing education to stay abreast of evolving practices and theories, ensuring they are equipped to provide the most effective support. Conducting comprehensive assessments that integrate information from multiple sources is also recommended. These assessments should aim to develop tailored intervention recommendations that support the child's mental health and well-being without pushing medical transitions.

It is crucial that assessments and interventions neither encourage nor discourage a child’s gender expression. The goal is to support the child in a manner that respects their self-identified gender needs. Assessments should thoroughly consider the child's environment, including family, school, and community contexts, utilizing multiple informants such as teachers, parents, extended family members, and other community figures to comprehensively understand the child’s situation.

Understanding the legal context in which the child lives is also vital. For example, if a child resides in Texas, it is important to know the specific legal implications for transgender youth in that state. Assessments might explore various dimensions such as the child’s gender identity and expression, any dysphoria or incongruence they experience, the strengths and challenges faced by the child and their family, experiences of gender minority stress, levels of support within the school, faith community, and extended family, potential conflicts within the family regarding the child’s gender, and the child’s overall mental health.

In comprehensive assessments for transgender and gender-diverse children, it's vital to gather a detailed medical and developmental history. This includes identifying any potential risks such as past trauma, abuse, suicidality, and co-occurring family stressors like chronic illness, homelessness, or poverty. Understanding the mental health of parents, caregivers, and siblings and the family's overall dynamics is also crucial.

Additionally, assessing the child's neurocognitive functioning and language skills is important. These factors can influence how accurately the child and their family report gender identity and expression. External pressures from family or school environments may compel a child to conform to certain gender expressions, and recognizing these influences is essential for accurate assessment and support.

Continuing education is imperative in this field. Professionals must stay informed about legislative changes, ongoing research, and evolving best practices. The recent introduction of the Standards of Care 8 underscores the importance of keeping knowledge current. In cases where it benefits the child and family, consultation or psychotherapy can be valuable, and it's crucial that this care coordinates with other aspects of the child’s life, such as school and faith communities.

Providing psychoeducation is a crucial element of working with transgender children and their families. Parents and children often require extensive information, especially as children approach puberty and begin considering their options regarding gender-affirming medical treatments. It is vital for healthcare providers to offer comprehensive details about available interventions, such as puberty blockers, ensuring that the family fully understands their effects and implications.

If a child expresses interest in exploring gender-affirming treatments, it is essential to discuss the potential impacts on fertility, as this is a common concern among families. Discussing fertility preservation options can help alleviate some anxieties about the future and aid families in making informed decisions. However, it's important to remember that if a child or their parents are not interested in these treatments, they should not be pressured or obligated to consider them.

Supporting a child's exploration of their gender identity is fundamental, whether or not they choose to socially transition. This support includes affirming the child's gender identity in a manner that respects their individuality and personal journey. It's also worth noting that a social transition can vary across different contexts. For example, a child might transition socially at home but not at school. Whether or not to disclose a social transition is a personal decision and should be guided by the child's comfort and safety, especially in environments where anti-trans legislation may affect their rights.

Additionally, it is crucial to address any concerns the family might have about sexual functioning, which can be a sensitive topic for some. While not all families will want to discuss this aspect, providing clear and age-appropriate information is essential for those who do. Furthermore, sex education should be introduced before puberty. This education should be inclusive, providing all children, including those who are transgender or gender-diverse, with the knowledge they need to understand their bodies and the changes they will undergo. This preparation concerns physical health and fosters a supportive environment that respects and affirms the child's developing identity.

When discussing social transition for transgender children, it is essential that the initiative for such a transition originates from the children themselves, not from assumptions made by their parents. For example, a parent should not deduce a child’s gender identity simply because they dislike traditionally gender-typed colors like pink and suggest the child might be a boy. Instead, the child should express their own desires and interests, and the transition should reflect their wishes.

Families can discuss with the child the advantages and disadvantages of social transitioning. It's important to note that social transition may occur in varying contexts; a child might transition at home but not at school, which is acceptable. Sometimes, a child may socially transition at a very young age, around 3 to 6 years old. In these cases, it's possible that neither their classmates nor their teachers are aware of the transition. This lack of disclosure is generally acceptable and often preferred to protect the child's privacy. This privacy should be respected unless external circumstances, such as anti-trans legislation, require disclosure. However, ideally, no one should be compelled to discuss their transgender identity involuntarily.

Exploring the risks and benefits of social transitioning is crucial. On the positive side, social transitioning can significantly enhance a child’s psychosocial adjustment and overall well-being. Research indicates that the mental health of socially transitioned children often parallels that of their cisgender siblings and peers, suggesting fewer mental health disparities than those observed in gender-diverse children and adolescents who have not transitioned socially. Supportive family environments frequently accompany these transitions and likely contribute to positive mental health outcomes.

However, there are potential downsides. Social transition may expose children to risks such as bullying or ostracism, particularly if they do not conform to established gender roles within their school or community. Additionally, the internal stress from experiencing gender incongruence can be a source of distress for gender-diverse children.

Importantly, all children, including those who are transgender and gender-diverse, have the right to be supported and respected in their gender identities. They are a particularly vulnerable group, and the social determinants of health significantly impact their well-being. For these marginalized minorities, robust support from families and schools is crucial, playing a critical role in fostering their health and overall development.

WPATH Standards of Care 8: Adolescents

Let's switch our focus to adolescents. When discussing this age group, we refer to the Standards of Care 8 outlined by WPATH. It’s important to note that the numbers I mention correspond to specific standards within these guidelines.

- 6.1 - We recommend health care professionals working with gender-diverse adolescents:

- 6.1.a - Are licensed by their statutory body and hold a postgraduate degree or its equivalent in a clinical field relevant to this role granted by a nationally accredited statutory institution.

- 6.1.b - Receive theoretical and evidenced-based training and develop expertise in general child, adolescent, and family mental health across the developmental spectrum.

- 6.1.c - Receive training and have expertise in gender identity development, gender diversity in children and adolescents, have the ability to assess capacity to assent/consent, and possess general knowledge of gender diversity across the life span.

- 6.1.d - Receive training and develop expertise in autism spectrum disorders and other neurodevelopmental presentations or collaborate with a developmental disability expert when working with autistic/neurodivergent gender-diverse adolescents

- 6.1.e - Continue engaging in professional development in all areas relevant to gender-diverse children, adolescents, and families.

- 6.2 - We recommend health care professionals working with gender-diverse adolescents facilitate the exploration and expression of gender openly and respectfully so that no one particular identity is favored.

- 6.3 - We recommend health care professionals working with gender-diverse adolescents undertake a comprehensive biopsychosocial assessment of adolescents who present with gender identity-related concerns and seek medical/surgical transition-related care, and that this be accomplished in a collaborative and supportive manner.

- 6.4 - We recommend health care professionals work with families, schools, and other relevant settings to promote acceptance of gender-diverse expressions of behavior and identities of the adolescent.

- 6.5 - We recommend against offering reparative and conversion therapy aimed at trying to change a person’s gender and lived gender expression to become more congruent with the sex assigned at birth.

- 6.6 - We suggest health care professionals provide transgender and gender-diverse adolescents with health education on chest binding and genital tucking, including a review of the benefits and risks.

- 6.7 - We recommend providers consider prescribing menstrual suppression agents for adolescents experiencing gender incongruence who may not desire testosterone therapy, who desire but have not yet begun testosterone therapy, or in conjunction with testosterone therapy for breakthrough bleeding.

- 6.8 - We recommend health care professionals maintain an ongoing relationship with the gender diverse and transgender adolescent and any relevant caregivers to support the adolescent in their decision-making throughout the duration of puberty suppression treatment, hormonal treatment, and gender-related surgery until the transition is made to adult care.

- 6.9 - We recommend health care professionals involve relevant disciplines, including mental health and medical professionals, to reach a decision about whether puberty suppression, hormone initiation, or gender-related surgery for gender-diverse and transgender adolescents are appropriate and remain indicated throughout the course of treatment until the transition is made to adult care.

- 6.10 - We recommend health care professionals working with transgender and gender-diverse adolescents requesting gender-affirming medical or surgical treatments inform them, prior to initiating treatment, of the reproductive effects, including the potential loss of fertility and available options to preserve fertility within the context of the youth's stage of pubertal development.

- 6.11 - We recommend when gender-affirming medical or surgical treatments are indicated for adolescents, health care professionals working with transgender and gender-diverse adolescents involve parent(s)/guardian(s) in the assessment and treatment process, unless their involvement is determined to be harmful to the adolescent or not feasible.

The first standard involves the requisite training, licensing, and credentials necessary when working with transgender adolescents. Importantly, while one does not need to be a mental health professional to assess a transgender-diverse adolescent, mental health professionals are generally best suited for this role. Typically, it is recommended that a mental health professional conduct assessments, especially those related to blockers, hormones, or surgery. However, a well-trained primary care physician could also competently perform this evaluation.

Additionally, those working with autistic or neurodivergent adolescents should seek ongoing training and professional development to ensure they are providing the most informed and effective care. It's crucial to facilitate the exploration and expression of gender in an open and respectful manner, ensuring that no specific identity is favored. This means avoiding any bias that might influence an adolescent either to embrace or reject a trans identity or to adhere strictly to the gender assigned at birth. The goal is to maintain a neutral, supportive space that allows youth to explore their identity at their own pace.

Conducting a comprehensive biopsychosocial assessment of adolescents is essential in a collaborative and supportive manner. It's important to recognize that not all children who are gender-diverse will continue to identify this way into adolescence. Similarly, adolescents may vary significantly in how quickly they consolidate their gender identity. This process occurs rapidly for some, while it evolves more slowly for others. This variability underscores the need to meet each youth where they are and proceed at a pace that respects their individual process.

Robust evidence supports the benefits of gender-affirming medical treatments in adolescents, but it's crucial to note that this evidence is based on clinical settings that incorporated detailed, comprehensive diagnostic assessments over time. There is no supportive evidence for making medical or surgical decisions without a thorough and prolonged assessment process. Therefore, the recommendation is clear: comprehensive diagnostic biopsychosocial assessments are necessary and represent the evidence-based approach for managing gender-diverse youth.

When working with families and schools, similar to interactions with children, it's crucial to avoid any approaches akin to reparative or conversion therapy. Such practices, aimed at changing a child's experience of their gender or eliminating gender incongruence, are not only ineffective but also harmful and unethical. Extensive research indicates that these methods can have detrimental effects on adolescents' well-being.

Health education on tucking and binding is also essential. If patients are engaging in these practices or are interested in doing so, it is important to provide proper guidance. Many teens might be tucking and binding unsafely, using materials like ace bandages or excessively tight tape, which can disrupt circulation and lead to issues such as back and chest pain, shortness of breath, and overheating. For example, one patient reported wearing two to three binders simultaneously, keeping them on while sleeping and during exercise, which is highly inadvisable. Binders are not meant for prolonged wear, especially not during sleep or physical activity, and should not be substituted with ace bandages. There are binders specifically designed for safe use, and these should be recommended instead. Notably, 87% of transgender masculine individuals, those designated female at birth who are transitioning to a more masculine identity, have a history of binding.

Discussing tucking, which involves retracting the testes and penis for a smoother appearance at the groin, is also crucial. This practice can affect sperm production and fertility, necessitating thorough educational support on these topics. Menstrual suppression is another consideration; it can be managed with various agents, regardless of whether the patient is using testosterone or puberty blockers. Some individuals may opt only for menstrual suppression without pursuing hormone therapy. Just as some cisgender women choose not to menstruate for personal comfort, similar options should be accessible for transgender individuals. Options include estrogen and progestin medications, oral progestins, and IUDs.

Puberty blockers, or GnRH (Gonadotropin-releasing hormones) analogs, can also suppress menstruation. However, testosterone, while it can suppress menstruation, may not immediately stop uterine bleeding, and breakthrough bleeding can occur. Importantly, testosterone is not a form of birth control and is teratogenic, meaning it can cause harmful effects on a fetus if pregnancy occurs. Therefore, it is vital to provide sex education and discuss birth control options with sexually active patients who could become pregnant, even if they are not menstruating. Ovulation and the potential for pregnancy can still occur in individuals using testosterone or puberty blockers who do not menstruate.

Providing ongoing support throughout the duration of puberty suppression, hormone treatment, or surgical interventions is crucial until the transition to adult care is complete. This process should not be limited to a single evaluation, after which the adolescent is sent on their way with prescriptions for hormones or puberty blockers. Decision-making is an ongoing process that requires constant support, especially as adolescents experience changes that might affect them differently than anticipated.

All of the research and evidence supporting these interventions were conducted in settings that fostered ongoing clinical relationships between the adolescents, their families, and their providers. This continuous support within multidisciplinary settings, where medical and mental health professionals collaborate closely, is essential for effective treatment. It’s important to understand that the evidence base comes from these types of collaborative environments.

Both medical and mental health professionals should be involved in both the initial evaluation and the ongoing care concerning blockers, hormones, and surgery. It’s not sufficient to have only mental health support; medical professionals must also be involved. While only one letter from a professional is required to proceed with treatment, this letter should reflect the entire team's comprehensive assessment and consensus, encompassing medical and mental health perspectives.

The multidisciplinary team might include professionals from various fields, such as adolescent medicine or primary care, which is often needed to confirm the stage of puberty. Endocrinologists may be required to prescribe hormones or puberty blockers, while psychologists, psychiatrists, and social workers address mental health aspects. Speech-language pathologists might be involved in voice training, along with support staff and the surgical team.

Discussing fertility is crucial when considering gender-affirming treatments for adolescents. It is essential to address the potential for fertility loss associated with various treatments and explore options for fertility preservation.

Puberty blockers are fully reversible, meaning they do not typically impact long-term fertility. However, transitioning directly from puberty blockers to hormones could potentially result in fertility loss. Furthermore, genital surgeries, although less common among adolescents, can have an irreversible impact on fertility. Therefore, discussing fertility preservation options, such as egg retrieval or sperm preservation, is important. It is vital that both parents and the adolescent understand the pros and cons of these options thoroughly.

Differences in perspective between parents and adolescents regarding reproductive capacity can lead to disagreements. Parents might place a high value on the potential for grandchildren, whereas the adolescent may express a clear disinterest in having children. Such disparities underscore the importance of facilitated discussions that help both parties understand each other’s viewpoints and the implications of treatment decisions.

It is also crucial to consider the adolescent’s decision-making competency regarding their future reproductive choices. While many adolescents feel certain about not wanting children, their desires and life circumstances could change as they mature. Guidance from professionals experienced in adolescent development and family dynamics is essential in these discussions. These professionals should help set realistic expectations for fertility preservation outcomes and ensure that these discussions are informed and based on the adolescent’s and family’s needs and values. These conversations need to occur both before initiating any medical intervention and throughout transition.

Fertility counseling is often recommended, even if preservation is not pursued. However, it is important not to coerce adolescents into fertility preservation if it is not aligned with their or their parents’ wishes. Procedures like egg retrieval can be distressing and physically uncomfortable, particularly for transmasculine individuals, due to the highly gendered nature of most reproductive health environments.

I'm currently working with an adult patient who was going through the egg retrieval process prior to continuing on testosterone. They experienced significant anxiety, partly because they had previously undergone the procedure. The environment, heavily feminized with images of women, did not align with their transmasculine identity, adding to their discomfort. They also found the process physically uncomfortable and painful.

These considerations must be navigated sensitively, ensuring that discussions about fertility preservation are inclusive and respectful of the adolescent’s gender identity and personal preferences. The decision to undergo fertility preservation is complex and must balance medical possibilities with the psychological comfort and personal desires of the adolescent, making professional guidance and open communication essential throughout the process.

It's crucial not to make assumptions about an adolescent's goals, especially given the limited research in this area. There is existing research involving childhood cancer survivors, which suggests that some participants experienced regret and distress over missed opportunities for fertility preservation. However, the experiences of transgender individuals may differ significantly.

Involving parents or guardians in both assessment and treatment is generally standard practice, with the assessment often occurring over multiple sessions—individually with the child, with the parents, and then together. This process can be extensive. Exceptions may occur, such as in cases where the adolescent is in foster care, under Child Protective Services, or where parental involvement might be harmful due to issues like abuse. However, in the majority of cases, parental or guardian involvement is crucial. Depending on the institution’s policy, consent from one or both parents might be necessary.

Parents and caregivers can provide valuable insights into the adolescent's gender development, medical and mental health history, and overall level of functioning. Discrepancies in reports between the adolescent and their parents about mental health can also provide critical information for understanding the youth's needs.

Working closely with parents is vital. It is essential to educate them about the treatment process, follow-up care, and potential complications. It’s important to take parents' concerns seriously and address their questions thoroughly, which can help in assessing the influence of peers or social media on the adolescent's understanding of gender.

There may be instances where parents do not consent to treatment. While some may still be generally supportive of their child’s gender identity, others may hold unsupportive or even antagonistic views. These perspectives, while challenging, are important to engage with as part of the therapeutic process. Many parents, with appropriate support and psychoeducation, may become more accepting and supportive of their trans and gender-diverse children over time.

Thus, continuing to work with families remains critical regardless of their initial stance on medical care. Even if a parent does not consent to specific treatments, supporting them can still positively impact the family dynamics and the well-being of the adolescent.

The following recommendations are made regarding the requirements for gender-affirming medical and surgical treatment (All of them must be met):

- 6.12 - We recommend health care professionals assessing transgender and gender-diverse adolescents only recommend gender-affirming medical or surgical treatments requested by the patient when:

- 6.12.a - The adolescent meets the diagnostic criteria of gender incongruence as per the ICD-11 in situations where a diagnosis is necessary to access health care. In countries that have not implemented the latest ICD, other taxonomies may be used, although efforts should be undertaken to utilize the latest ICD as soon as practicable.

- 6.12.b - The experience of gender diversity/incongruence is marked and sustained over time.

- 6.12.c - The adolescent demonstrates the emotional and cognitive maturity required to provide informed consent/assent for the treatment.

- 6.12.d - The adolescent’s mental health concerns (if any) that may interfere with diagnostic clarity, capacity to consent, and gender-affirming medical treatments have been addressed.

- 6.12.e - The adolescent has been informed of the reproductive effects, including the potential loss of fertility and the available options to preserve fertility, and these have been discussed in the context of the adolescent’s stage of pubertal development.

- 6.12.f - The adolescent has reached Tanner stage 2 of puberty for pubertal suppression to be initiated.

- 6.12.g - The adolescent had at least 12 months of gender-affirming hormone therapy or longer, if required, to achieve the desired surgical result for gender-affirming procedures, including breast augmentation, orchiectomy, vaginoplasty, hysterectomy, phalloplasty, metoidioplasty, and facial surgery as part of gender-affirming treatment unless hormone therapy is either not desired or is medically contraindicated.