Editor's Note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Evidence-based Treatment for Social Anxiety Disorder in Teens, presented by Janelle Youngdahl, PhD, LP, NCSP.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to describe the etiology and presentation of social anxiety disorder.

- After this course, participants will be able to explain the consequences and co-morbidities of social anxiety disorder.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify evidence-based treatment options for social anxiety disorder.

Introduction

Thank you so much. I am excited to talk about social anxiety disorder today, specifically in teens, and what the evidence-based treatment options are.

Limitations and Risks

- This presentation is a broad overview of the presentation and treatment of social anxiety disorder in teens. Information from this presentation should not be used to make a formal diagnosis. Only trained and qualified professionals should implement the treatment strategies that will be discussed. This presentation is not a substitute for supervision or therapy.

- Content material may be sensitive or triggering due to nature of discussing mental health concerns.

The limitations and risks of this presentation are that this presentation is a broad overview of the treatment of social anxiety disorder. Information should not be used to make a formal diagnosis on its own, and only trained, qualified professionals should implement these treatment strategies that will be discussed. Additionally, this presentation is not a substitute for supervision or therapy. Finally, the content material may be sensitive or triggering due to the nature of discussing mental health concerns and some of the consequences.

Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD): Diagnostic Criteria

- Intense fear of being judged, negatively evaluated or rejected in social situations

- Must occur in peer settings for teens

- Social situations almost always provoke fear

- Social situations are avoided or endured with intense fear

- Fear is out of proportion to the actual threat, persistent, and causes impairment of functioning

Social anxiety disorder is categorized by the intense fear of being judged, negatively evaluated, or rejected in a social situation. The fear of being negatively evaluated in a social setting has to be with peers or same-aged or similar-aged individuals. Social situations must almost always provoke intense fear, not some of the time or every once in a while. Social situations are avoided or endured with an intense fear that exceeds the actual threat. For example, a person could have an intense fear about a school presentation that would be out of proportion to what the threat of that presentation would normally cause. The fear is persistent and causes impairment of functioning. We will talk more about this impairment of functioning piece when we get into the consequences.

Development

- Median age of onset: 13 years

- Heredity

- Predisposing traits are strongly genetically influenced.

- Temperament

- Behavioral inhibition

- Fear of negative evaluation

- Environment—learned behavior

- Experiencing stressful/humiliating event or repeated negative evaluation

- Socially anxious modeling parents

In social anxiety disorder, the median onset is 13 years old or right at the beginning of the teenage years. This is when we see social anxiety most commonly popping up and developing. A few broad factors that can increase the risk of developing a social anxiety disorder are heredity, temperament, and environment/learned behavior. Anxiety disorders and symptoms run in families, and anxious traits can be inherited. I will talk a little bit more about the environmental piece, but that is one of the ways that we can see anxiety developing within a family system. Temperament can also influence the development of a social anxiety disorder, specifically in individuals with higher behavioral inhibition and a sense of being concerned about negative evaluation. Finally, the environment and learned behavior are influential. For example, suppose a teenager experiences a stressful and humiliating event or has repeated negative evaluations from peers. In that case, this learned behavior will be influential in potentially developing a social anxiety disorder. Considering the hereditary influence on social anxiety disorder, parents with social anxiety disorder can display socially anxious behaviors, which the teenager can model.

Key Signs and Symptoms

- Avoidance of social situations

- Feelings of shame, humiliation, and embarrassment

- Physical symptoms

- Inadequate eye contact and/or speaking in soft voice

Some key signs and symptoms of social anxiety disorder are persistent avoidance of social situations, intense feelings of shame, humiliation, and embarrassment, and physical symptoms like a racing heart, blushing, excessive sweating, dry throat and mouth, trembling, muscle twitches, and shortness of breath. These physical symptoms are seen in the anticipatory phase and during social situations. They also display inadequate eye contact and a soft speaking voice. They avoid looking at people and try to fly under the radar, almost appearing to be shy in some instances.

Common Fears

- Attending social events

- Talking to authority figures

- Attending school

- Being teased

- Being the center of attention/being watched

- Having to speak in a formal, public setting

- Interacting with new people

Some common fears I have encountered when working with individuals with social anxiety disorder are attending social events, school sporting events as spectators or participants, birthday parties, homecoming dances, or any time there is a large group. They also do not like to talk to authority figures like teachers, doctors, therapists, and friends' parents. These are all commonly feared situations.

It is hard to avoid social situations at school, so this environment is often paired with fear. Teens do not want to go to school because they have to see all of their peers, and they can negatively evaluate them. They worry about being teased, made fun of, or the center of attention. They feel like all eyes are on them, whether that is an actual situation or something that they are worrying will happen. They do not like to speak in a formal or public setting. This could range from giving a presentation in front of a class to getting called on in the classroom. Lastly, they do not like to interact with new people. They can be anxious about the first day of school, the first day of summer camp, going to an extracurricular activity, or situations where they are not sure who is going to be there.

Consequences

- Increased rates of school refusal and school dropout

- Lower employment levels, workplace productivity, and socioeconomic status

- Decreased well-being and quality of life

- Lack of relationships (social or romantic)

First, as I mentioned earlier, some of the main consequences are school refusal and school dropout. There are so many social expectations in the school setting, and because that is a feared setting for teenagers with social anxiety disorder, it is commonly avoided. It could be for weeks, months, a year, and even lead to the student doing virtual schooling or homeschooling. Or it could lead to the student dropping out altogether.

As teenagers age and enter into early adulthood, we see lower employment levels for similar reasons as school refusal or low school attendance. Work is a social setting, and you have to interact with people. There is lower workplace productivity and decreased attendance in meetings, group projects, and reaching out to ask questions. Decreased school attendance and poor employee productivity can lead to a lower socioeconomic status.

As you might imagine, there is decreased well-being and quality of life, with a high, intense level of anxiety for a large portion of their lives. Many things in our lives are socially laden, like going to school, the grocery store, walking down the street, and shopping. With a social anxiety disorder, a person feels anxious most of the time. If they avoid social situations, they are not getting out and doing things that could bring joy, or the things they used to do are now more challenging.

Similarly, they have a lack of social and romantic relationships. Social relationships are complicated for these individuals, as they find it hard to seek out, initiate, and maintain relationships.

Common Co-morbidities

- Other anxiety disorders

- Specific phobia

- Separation anxiety disorder

- Generalized anxiety disorder

- Selective mutism

- High functioning ASD

- Major depressive disorder

- Chronic isolation

- Substance use disorders

- Self-medicating

Some common co-morbidities of social anxiety disorder are other anxiety disorders, specific phobias related to social settings, or a humiliating or stressful social event that happened in the past. Individuals with social anxiety disorder have comfortable and familiar people they do not feel anxious with, like best friends, parents, or siblings. Separating from them can be very difficult and add an additional layer. Uncontrollable worries, restlessness, and decreased concentration can indicate a generalized anxiety disorder. Selective mutism can also occur in social situations. The person does not want to be seen or heard. There can be some overlap with those diagnoses as well.

Those with high-functioning autism can also have social skills deficits. They do not feel comfortable in social situations because they cannot relate to other social peers. They withdraw from those activities because they recognize their deficits. Individuals with social skills deficits on the spectrum may have more negative peer evaluations and experience more stressful and humiliating social events. Thinking back to the development of social anxiety disorder and learned behavior, it makes sense that this population would have a higher risk of social anxiety disorders.

I touched on major depressive disorders and decreased well-being. With a social anxiety disorder, on top of that, there can be chronic isolation and difficulty leaving home.

Finally, substance use disorders coincide with social anxiety disorders as many individuals turn to substances to self-medicate, help them calm down, and quiet their symptoms.

Assessing for Social Anxiety Disorder

- Diagnostic interview

- Broad and narrow-band rating scales

- Child Behavioral Checklist (CBCL)

- Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A)

- Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED)

- Youth Self-Report (YSR)

- Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS)

- Severity Measure for Social Anxiety Disorder (SMSAD)

(Carlton et al., 2022; Nishikawa et al., 2022)

To assess for social anxiety disorder, you must do a detailed diagnostic interview, including talking to the teenager, parents, and teachers. They will provide important information about whether or not they meet the criteria for a social anxiety disorder.

Some good broad and narrow-band rating scales can also be used to look specifically at some of these symptoms. The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) is a broad-band behavioral checklist that looks at all behaviors, including anxiety. The Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A) is excellent for this population to identify symptoms, specifically social anxiety. The SCARED, Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders, is specifically for anxiety-related disorders and is a narrow-band scale. The Youth Self-Report (YSR) is another broad-band tool that looks at different behaviors, including anxiety. The Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS) looks at social interactions relevant to social anxiety disorders. Finally, the Severity Measure for Social Anxiety Disorder (SMSAD), which I will talk about more in a moment. These are some of the most commonly recognized rating scales looking to assess for social anxiety disorder and get a better idea of what the symptoms are.

Monitoring Symptoms

- Severity Measure for Social Anxiety Disorder

- Valid and reliable measure for assessment and progress monitoring

- Measures the severity of social anxiety symptoms

- Age range: 11-17

- 10-items

- Can be regularly administered to track progress

(Carlton et al., 2022)

The Severity Measure for Social Anxiety Disorder is excellent for assessing and monitoring symptoms. It is a valid and reliable measure for both of these and is appropriate for ages 11 to 17. It can be given regularly to track progress at the beginning of each therapy appointment to measure the severity of the social anxiety symptoms that that individual is experiencing. It is brief with ten items.

Many people will also have clients complete a PHQ before their session. This is similar to that, specifically for social anxiety disorder. As stated, it monitors symptoms over time to see if they improve or worsen. We can also look at specific weeks. For example, their symptoms could be severe one week, and we can track the triggers that may have led to that. I am getting ahead of myself, but this is a good start for intervention.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

- CBT is considered the gold-standard therapy approach for treating social anxiety

- Exposure + cognitive restructuring (Stefaniak et al., 2022)

- Social anxiety disorder responds well to cognitive behavioral therapy in terms of symptom reduction and diagnosis remission (Yang et al., 2018)

Research has shown that cognitive behavioral therapy is the gold standard for treating social anxiety disorder. Specifically, the exposure and cognitive restructuring pieces that fall within cognitive behavioral therapy are the most commonly utilized and effective for treating this disorder (Stefaniak et al., 2022).

Yang and colleagues found that social anxiety disorder responds well to CBT for symptom reduction and diagnosis remission. This is the first line of treatment we use for individuals with social anxiety disorder.

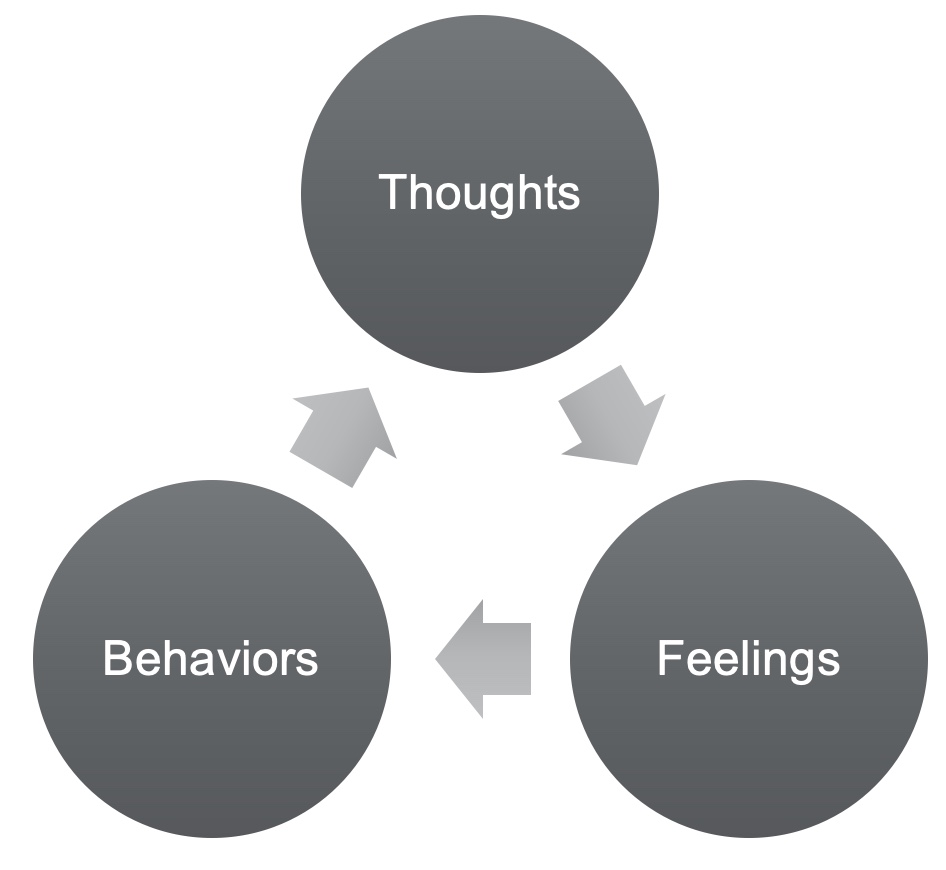

Before I get into the specifics of this, I want to give an overview of cognitive behavioral therapy, theoretically and conceptually. Cognitive behavioral therapy focuses on our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, specifically how those all interact cyclically, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Conceptual theory of CBT.

Our thoughts impact our feelings, which affect our behaviors and thoughts, which influence our feelings, and so on. Cognitive behavioral therapy, as indicated by the name, focuses on the behaviors and thoughts of this cycle. These are the critical areas of intervention for CBT. We are going to intervene at the behavioral and thought levels.

An example is a thought, "No one at school likes me." An individual's feelings associated with that thought are probably sadness, anxiety about going to school, feeling lonely, upset, and stress. If one has those feelings, they are likely to engage in behaviors consistent with feeling that way, such as avoiding school, staying home, drawing their blinds, taking a nap, isolating themselves, and socially withdrawing. If they engage in those behaviors, negative thoughts will continue to happen or increase. This is how we see that cycle happening. Again, CBT is working to intervene at that behavioral and thought level. Even if they are anxious, upset, or sad, what can we do with this behavior and thoughts to break the cycle?

CBT: Thoughts

- Strategies for Addressing Unhelpful Thoughts

- C-C-C (catch it, check it, change it)

- Identification/labeling

- Check for helpfulness or likelihood of thought

- Replacement thought

- Thought responding

- Mantra

- Cognitive restructuring

- Thought record

- Challenging worry thoughts

- C-C-C (catch it, check it, change it)

C-C-C

I will start with the thought portion. The strategies that I will be focusing on today are broader overviews. We want them to catch the thought, check it, and change it. They first need to identify when they have an unhelpful idea, label it, and put it into a category, which I will describe in a second. They then need to check it for helpfulness or the likelihood of that thought occurring. Lastly, they need to change it by coming up with a replacement thought or doing something to manipulate that unhelpful automatic thought. The example that I give when working with my clients is I ask them to visualize an airport and the security checkpoint. We want to put our thoughts through a security checkpoint before they can live in our heads. When an unhelpful or negative thought enters that security line, we want it to set off an alarm so we can further inspect it. Is this thought likely, realistic, or the truth? Like the airport security with a wand, they want to change something about it. If they identify that it is an unhelpful thought, they need to change it. We want them to change it, make it more helpful and less bothersome, and then put it back through that security point until it can pass through. We do not want these thoughts to roam around in their brain. We need to put them through this evaluation procedure. I will talk more about the change piece in detail when I talk about cognitive restructuring.

Thought Responding

Another strategy is thought responding or restating. A way to do this would be to develop a mantra when an unhelpful thought pops into your head, like "My thoughts do not control me" or "I make mistakes sometimes." You ask your client to restate their thought, such as, "My mind is telling me that no one likes me," or, "I'm having a thought that no one likes me." This is in contrast to the statement "No one likes me" as an absolute fact. Facts are indisputable, and they feel like they are true. If the statement is not worded as an absolute fact, we can do some restructuring around that and poke some holes in the argument.

Cognitive Restructuring

Cognitive restructuring is the "change it" part of the CCC process. Two specific ways to restructure our thoughts are challenging the worry thoughts and a thought record. Figure 2 shows an example of the thought record, but before I go into the specific pieces, I want to give a broad overview of cognitive distortions in case that is not a well-known concept.

A cognitive distortion is unhelpful thought patterns that automatically pop into our brains, translating into a thinking error. It is a thought that is unhelpful and probably not true. I tend to tread lightly with the error piece when I work with clients because I do not want them to feel like their thoughts are invalid. I tend to say, "It's an unhelpful thought." Even if they believe that it is valid, we can at least agree that it is not helpful. There are ten different patterns of negative thoughts that can fall into these cognitive distortions, and going back to the "catch it, check it, change it" strategy, cognitive distortions fall in the "catch it" category as we are labeling and identifying it.

Thought Record.

A thought record is a way for clinicians and therapists to work through some of this restructuring formally, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Example of a thought record.

The first column is the situation or what was happening when the thought occurred, and the second column is the automatic thought. The third column is the cognitive distortion category that the thought falls into, while the fourth is a replacement thought. I describe this to my clients as a planner. Remembering what you must do is difficult, and putting it on paper clears some space in your mind. It is similar to unhelpful thoughts in our brains. The thoughts can feel overwhelming, and we may feel like we need to hold onto them. If we can get them down on paper, we can maybe put them to the side and come back to it later. A thought record helps us formally restructure our thoughts and gets our thoughts out of our brain momentarily.

Let's go through a few examples. A client misspoke during a presentation in front of their class, which sent them spiraling. The automatic thought was, "I never do anything right. My classmates will make fun of me forever, and no one will want to be my friend." We will catch this thought and figure out what category it is.

While I did not specifically talk about all of the cognitive distortion categories, I will explain the ones in these examples. One is overgeneralizing, where a pattern is drawn based on a single event. I tell my clients to look for keywords that are outliers in their thoughts which can lead us to think this could be overgeneralizing. The keywords for overgeneralizing are never, anything, forever, and no one. These are extreme outlier words. "I never do anything right." You have never done anything right in your entire life? It is an overgeneralization. Catastrophizing or magnification is blowing something a little out of proportion. You misspoke during a presentation, so you will never have any friends again? It is worst-case scenario thinking. Jumping to conclusions is where you are predicting the future. "Everyone's going to make fun of me forever." We are catching an unhelpful thought and categorizing it.

The next step is to come up with a replacement thought. I will preface this by saying that I recommend my clients come up with a neutral middle-of-the-road replacement thought. I do not want them to come up with an opposite positive thought because I do not think it is realistic that they will use that replacement thought. For example, the opposite positive of the automatic thought in this example would be, "I always do everything right. My classmates never make fun of me; everyone wants to be my friend." While it would be great if someone thought that, it is unrealistic. It is too big of a jump to go from "I never do anything right" to "I do everything right." We want them to come up with something neutral, heading toward positivity. We want them to take the negative thought, come up with the absolute opposite, and find something in the middle. As time moves on, the thoughts will generally trend towards more positive on their own. Neutral is just a good starting point. With that in mind, a replacement thought for this situation would be, "Sometimes I make mistakes. My classmates probably won't remember this tomorrow. My friends like me even though I'm not perfect." Again, this is not the most positive statement, but I'm sure it will bother the client much less if they can think this thought versus the original.

The following situation is an upcoming school dance. The automatic thought is, "Everyone will stare at me and make fun of my outfit. I'm a loser, so I won't have anyone to talk to, and I will have a terrible time." We see jumping to conclusions and catastrophizing. We also see something new in this one, which is labeling. "I'm a loser." The replacement thought for this could be, "People haven't made fun of the clothes I have worn before. I know a few people who will be there, and they are usually friendly to me. I'll probably have fun for at least part of the time." It is not overly positive, but it is more likely that the client will use that replacement thought than an overly positive one.

This is the thought record procedure. Again, the client needs to get it on paper so they have a formal format to work through to get it out of their brain and engage in active cognitive restructuring.

Challenging Worry Thoughts.

- What's the worst that can happen? Can I handle that?

- What happened in a similar situation in the past?

- What evidence do I have that this thought is untrue?

- Is there a more likely outcome?

- Am I 100% sure that what I'm worried about will happen?

The next part of cognitive restructuring for social anxiety disorder that is helpful is challenging worry thoughts. These five questions are the typical questions that I will use with clients when we examine the evidence against the worry thoughts. Not every single one of these questions will apply to each worry thought, but usually, one or two of them will apply.

The first is, "What's the worst that can happen?" and the second is, "Can I handle that?" When we have anxiety thoughts, there is usually an unknown where we do not know what will happen in the future. We tend to fill that empty gap of the unknown with a worst-case scenario thought, or "Whatever it is not going to be good." We can work with the teen to generate lists of the worst that can happen. You may be thinking, why would I want to shed light on all the bad things that could happen to them? However, putting things down on paper makes them less scary, or there may be less than the client initially thought. Unfortunately, there will be situations when the worst-case scenario does happen. You can help them shift to how they can handle that if it does happen. Again, our anxiety tells us that we should fear these situations because they are terrifying, and we would not be able to deal with them if they happened. I like to change that and remind clients of all the times they have handled hard things in the past. So worst-case scenarios have happened. "I'm so sorry about that. How did you handle it?" We can also ask how they managed that. Thinking about past difficulties puts them in the mindset that they can handle hard things. Even if the worst-case scenario does happen, it is usually not as bad as they think, and it gets them to generate some ideas.

The next question is, "What happened in a similar situation in the past?" While we cannot predict the future, patterns of past behavior can sometimes give us a good idea of what might happen in the future. Asking patients or clients to think back to times when they had a school presentation, went to a sporting event, attended school, et cetera, may help them. "What happened the last time you attended school? Walk me through that day." Usually, there are not a lot of worst-case scenario situations that have happened in previous situations. Again, there may be some, and we have talked about how to manage that, but usually, they can say, "I went to the game, and my friend met me at the door. I walked in with her, sat with her the whole game, and our team won. It ended up being pretty fun." You can then say, "If that happened last time, what do you think would be different about the next time you go?" Or, "If you're worried that the next time's going to be horrible, what do you think will change?" They may say, "It ended up better than I thought."

What evidence do I have that this thought is untrue? We always want to remind our clients of the times when they worry about something that does not end up happening. We tend to sometimes focus a lot on anticipatory worries and anxiety. For example, they may think they will fail a math test, but then they do not. In this situation, we should circle back and remind them, "You were so worried about this. What ended up happening?" You can remind them that they were worried about things in the past that did not end up coming true. "Some things may end up coming true, but this is something we need to work through.

The next one I talk about is, "Is there a more likely outcome?" They have this list of worst-case scenarios, and now we want them to shift to "What is a more likely outcome?" The next one is, "Are they 100% sure that what they are worried about will happen?" I usually take a playful approach with clients when discussing this question. if they are worried about everyone making fun of their outfit and they are not going to have anyone to talk to, I might say, "Are you 100% sure that's going to happen? Would you be willing to bet a week's worth of video games on it?" or "I'll bet $100 on it." They usually say, "No, I'm not 100% sure that it's going to happen," because they cannot predict the future.

The following line of thinking is, "Can I delay thinking about it until if/when I need to?" In this situation, I illustrate that when we worry about something that does not end up happening, we spend a lot of time worrying. They have to deal with it anyway, so they might as well not have spent the week prior, spending a lot of time and energy thinking about it. In the best-case scenario, they spent a week thinking about something when they did not have to worry. In the worst-case scenario, they have to deal with it for twice as long. This is the point that I try to bring home. We do not know 100% that something is going to happen. Thus, we try to delay it and manage symptoms by putting off thinking about it until we have to if it does come true.

"What evidence do I have that this thought is untrue?" If you ask a teenager with social anxiety disorder, "What's the evidence you have that this thought is true?" they will give you a long list. We want them to provide evidence that it is false, as that is the hard part. They have to put in more work. An example I use for this is a debate activity at school. "Let's imagine there is a debate about the best season. Your first automatic thought might be summer as there is no school, nice weather, and you can hang out with your friends. However, your teacher says that you must argue that winter is the best season. That might be hard because you do not think winter is the best season. So to get a good grade, you generate the list of reasons winter is the best season and poke holes in your opponents' arguments about summer. By the end of that debate, you may still think summer is the best season, or you may have even changed your mind. Still, either way, you can see a couple of holes in the argument." This is a great scenario to show a teen that when we do this with our unhelpful or "worry" thoughts, the worry thought is going to be the automatic one that we support. Still, if we debate the other side and come up with at least three pieces of evidence that the thought is untrue, it takes power away from that thought. They may not believe the alternative thought completely, but it takes control away from the initial one and makes the anxiety seem less powerful and credible.

CBT: Behavioral Strategies

Shifting more towards the behavioral parts of cognitive behavioral therapy and the treatment for social anxiety disorder, we will talk about relaxation strategies and then systematic desensitization or exposures.

- Relaxation

- Diaphragmatic breathing

- Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR)

- Mindfulness

- Exposure

- Systematic desensitization

The relaxation strategies I will talk about are diaphragmatic breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, and mindfulness.

Diaphragmatic Breathing

- Promotes full oxygen exchange

- Lowers heart rate and blood pressure

- "Chest Breathing" > "Belly Breathing"

- Breathe in through nose, out through mouth

- One hand on chest and one on belly

Diaphragmatic breathing is breathing in through your nose, holding it, and breathing out through your mouth to promote a full exchange of oxygen. This full breath improves physiological symptoms associated with anxiety, like lowering heart rate and blood pressure. It makes us feel better from the outside to the inside. Compared to the other relaxation strategies, this is the one I hear about the most. Many teens say this does not work, and I think it is because most take a couple of deep breaths and quit. That does not work. To promote the full exchange of oxygen and reap the benefits, we need to move from chest-breathing to belly-breathing. What I say, which is oversimplified, is "With regular breathing, air goes into our body, stops at our chest, and comes right back out. What we want to do for diaphragmatic breathing is to push that air down to our belly." I have clients put one hand on their chest and one hand on their belly, take a deep breath through their nose and feel their belly inflate. I will sometimes even say, "Imagine you are blowing up a balloon in your belly, and when you blow out, the balloon deflates." They should spend about 5 to 10 minutes on this cyclical breathing pattern to see results.

Progressive Muscle Relaxation

- Reduces body tension and relieves physical symptoms

- Deep breathing + tightening and releasing muscles

- Inhale while tightening muscle, hold 5-10 seconds, exhale while releasing

- Imagery as a helpful addition

- What the muscle looks like when tense and relaxed

- Stress/tension/thoughts leaving your body when muscle is released

Progressive muscle relaxation is the tightening and releasing of muscles progressively, starting with the toes and working your way up to your forehead. You can also add some deep breathing during that. Ordinarily, I would start with my toes, but as an example, I will demonstrate this with my hand. Take a deep breath and tighten your hand into a fist for 5 to 10 seconds. Release while exhaling a deep breath out.

Imagery can also be helpful for deep breathing and progressive muscle relaxation. Some clients prefer to visualize what their muscles look like when they are tense, like tight fibers. And then when they release, maybe that looks like loose fibers. Other clients like to visualize like they are collecting all the worry thoughts and squeezing them. When they release, they may blow their worries away like dandelion fluff.

Imagery, in addition to deep breathing and progressive relaxation, can be a nice trifecta leading to a reduction of body tension and physical symptoms.

Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy

- Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) increases self-esteem and self-concept and decreases symptoms of social anxiety.

- Symptom reduction: physiological symptoms, fear, and avoidance

(Raee et al., 2022)

The next broader category of strategies is mindfulness relaxation strategies. Research has shown that mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral therapy works specifically well with social anxiety disorder. It increases self-esteem and self-concept and decreases symptoms of social anxiety, like physiological symptoms, fear, and avoidance.

- Mindfulness Strategies

- Guided meditation

- Listen and follow along

- Guided imagery

- Visualize "happy place"; add detail using 5 senses

- 5-4-3-2-1 grounding technique

- 5 things you see, 4 things you can touch, 3 things you can hear, 2 things you can smell, 1 thing you can taste

- Mindful activities

- Pay attention to your 5 senses in the moment while completing an activity/task

- Guided meditation

Mindfulness looks like a couple of different things. One is guided meditation for clients who are slightly more reluctant to engage in relaxation strategies. I usually start with this because it is a listen-and-follow procedure. They can get an app on their phone or go on YouTube and search for guided meditation for anxiety. A calm voice will walk them through the process of doing some of these relaxation techniques.

Guided imagery is another good one where you ask the client to visualize a happy place or a fond memory using as much detail as possible and their five senses. For example, if it is a trip to the beach, ask them what they see and hear and who is with them. You can also ask who is with them and what the temperature is. "Tell me about a happy memory" or "Tell me about a time when" are opening questions, and you can get increased details by asking questions. Additional questions can be what they are wearing, the time they left, how far the beach is from where they parked, did they bring a towel and chair, and so on. You ask these questions as it will be hard for them to come up with many of those details on their own.

The five, four, three, two, one grounding technique is the five things you see, four things you touch, three things you hear, two things you smell, and one thing you taste. This technique can be done wherever you are, bringing you intentionally back into the moment of feeling your senses.

I always say you can do anything mindfully. If baking cookies or taking a shower, they can pay close attention to their senses during that activity. Mindfulness does not need to add anything to their schedule.

Worry and Exposure Cycles

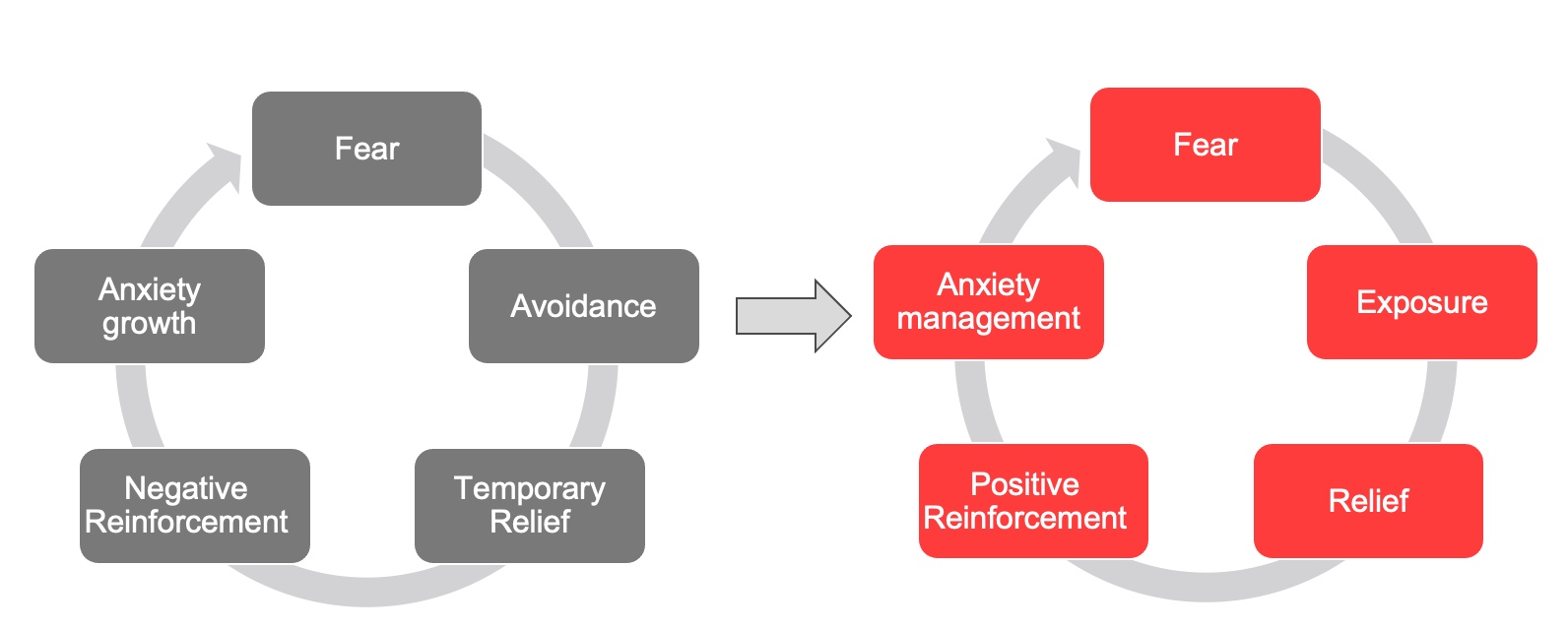

Before discussing exposure, I want to review the avoidance and exposure cycles in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Avoidance and exposure cycles.

The avoidance cycle is on the left here, where a lot of social anxiety lives. You avoid the feared situation and feel temporary relief. Avoidance is negatively reinforced because of that temporary relief which leads to the anxiety growing. The next time you experience a feared situation, you think the only way you will feel better is if you do not do it. So you continue to avoid fearful situations, and your world gets very small.

If we shift to the right, there is a feared situation. You do it anyway and then feel relief because it is done. The relief positively reinforces exposure, and the anxiety is more managed. That is the cycle where we want to move clients. Remind them that you can feel relief from the exposure like you can from the avoidance.

Systematic Desensitization

- Gradual exposure to feared situation

- Imaginal

- Virtual reality

- In-vivo

- Paired with relaxation strategies

- Utilization of exposure/fear hierarchy

With exposures, we want to use this systematic desensitization model. It is a gradual exposure to the feared situations. This can be done in an imaginable way. For example, "I want you to imagine giving the presentation in front of the class," or "I want you to imagine walking into that football game." It can be used with virtual reality, which is cool, now that technology is increasing. They can also do it in-vivo.

We want to pair these relaxation strategies with systematic desensitization with relaxation strategies to make the person as comfortable as possible for the client during the exposure. Relaxation strategies before and during the exposure can help to make the experience less uncomfortable for them.

We want to use a fear or exposure hierarchy so we know what an excellent next step exposure-wise is and what would be something too many steps ahead. In a minute, I will discuss fear hierarchies and give examples. But first, I wanted to revisit the virtual reality piece because research has shown that this can be helpful in exposure and cognitive behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder.

Virtual Reality as Therapy Tool

- Recent research indicates VR as helpful option for exposure

- Easier to organize exposure situation

- Gives therapist control over the situation and intensity of exposure

(Stefaniak et al., 2022; Horigome et al., 2020)

Specifically, virtual reality makes it easier to organize exposure situations because you can create the simulation. You do not have to coordinate with schools, peers, or community members to set that up. It also gives the therapist more control and intensity of the exposure. For example, I can create exposure with someone in my office. We can plan in-vivo situations as much as we can, but perhaps there is a substitute in the class, an unruly student, or someone who makes a negative comment to them. I cannot control for those variables or the intensity. Maybe it was easier than I thought it would be, or perhaps it was more complicated than I thought it would be.

With virtual reality, I can make the situation as intense as I want with specific variables. It can be a helpful tool for social anxiety exposure for social anxiety, mainly because the exposures require the participation of other peers, which can be hard to control.

Exposure Hierarchy Examples

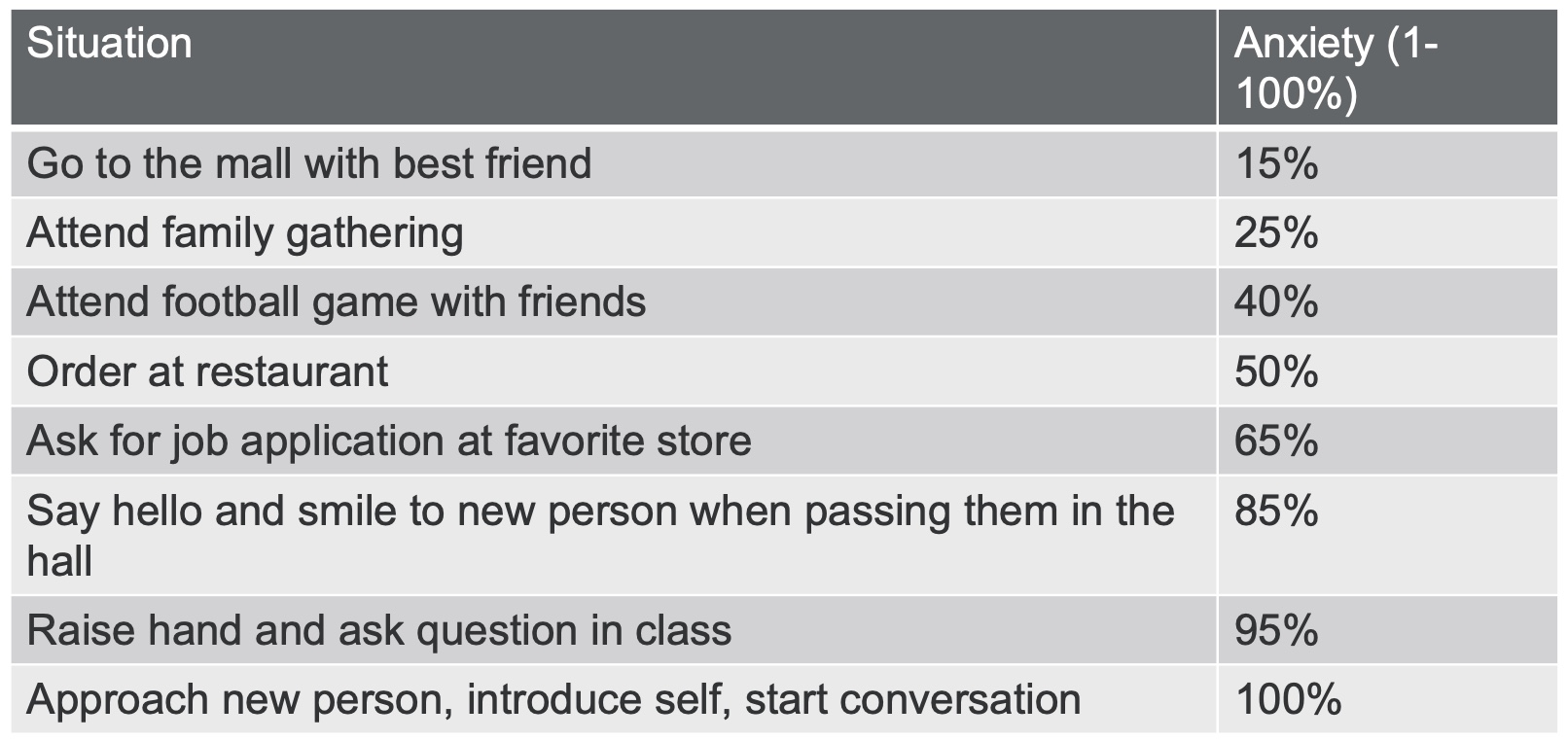

I am going to give two examples of exposure hierarchies. Figure 4 shows one.

Figure 4. Exposure Hierarchy Example 1.

The first is unrelated tasks, all related to social situations. You have them rate their anxiety for the tasks from 1 to 100. One is the situation does not make me anxious at all, and 100 makes me very anxious. You have them come up with different situations that they would ideally like to do and have them rank these in order. You then start with the one that is the easiest. In the example, the teen wants to go to the mall with their best friend. Have them practice that until the 15% goes down to 0% or 5%. You then move to the following scenario.

It is also essential to update these exposure hierarchies because you never want a client to do an exposure in which they are rating a 100% anxiety level. That expectation is too high, setting them up for failure or a bad experience. You do not want to go from step A to step D. You want to go from A to B, then B to C, and so on. You want each step to feel slightly out of their reach and comfort zone, but they think they can do it. This contrasts with them standing at the bottom of a mountain and looking up at something they do not feel comfortable doing. This is why these exposure hierarchies are so critical. They may say, "Since the last time I saw you, I attended a football game with my friends, and it was fine." We would take off that goal and replace it with another one.

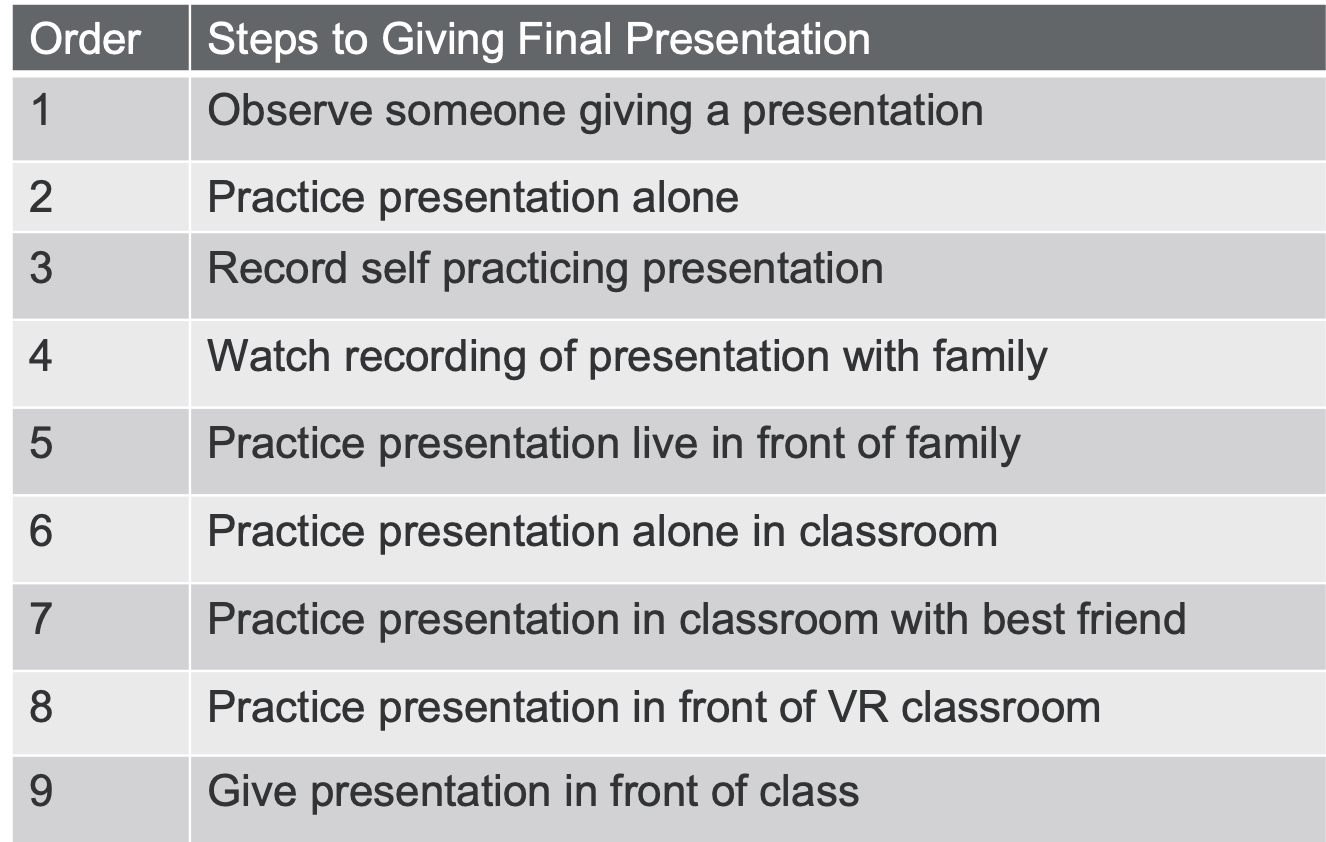

Figure 5 shows an example of an exposure hierarchy that specifically breaks down the steps to one final goal in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Exposure Hierarchy Example 2.

This example is giving a final presentation. A task is broken down into different steps to get the client from where they are currently to the final goal of giving the presentation. They then rank order those steps. First, they are going to start by observing someone giving a presentation. Next, they are going to practice that presentation alone in their room. They will then record themself practicing that presentation and watch it with their family. They move to do it live in front of their family. They do the presentation alone but now in the classroom. The next step is that the best friend will be in the classroom, or maybe they will do it in a virtual reality classroom. Lastly, they give the presentation in person. This example shows breaking down those steps of one task, rank-ordering them, and then doing that systematic desensitization for each to move up the list.

Summary

- Definition: intense fear of being judged, negatively evaluated, or rejected in social situations

- Consequences: increased school refusal/dropout, lower SES, decreased quality of life, and lack of relationships

- Treatment: CBT focusing on cognitive restructuring and systematic desensitization

- Treatment Outcomes: symptom reduction, improved coping skills, diagnosis remission

Here is a summary of what we talked about today. The definition of social anxiety disorder is an intense fear of being judged, negatively evaluated, or rejected in social situations. The consequences of social anxiety disorder are increased school refusal and dropout, leading to lower socioeconomic status, decreased quality of life, and lack of social and romantic relationships.

The gold standard treatment for social anxiety disorder is cognitive behavioral therapy, focusing specifically on cognitive restructuring. Cognitive restructuring uses the catch it, check it, change it technique, doing a thought record, or challenging the worry thoughts. Systematic desensitization, relaxation strategies, exposure, and fear hierarchies can also be used. Cognitive behavioral therapy leads to symptom reduction, improved coping skills, and diagnosis remission. It is an effective, evidence-based treatment for social anxiety disorder.

I hope you learned much more about social anxiety and feel more comfortable treating it and working with clients who experience it.

References

Carlton, C., Gargia, K., Richey, J., & Ollendick, T. (2022). Screening for Adolescent Social Anxiety: Psychometric properties of the severity measure for social anxiety disorder. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 5, 237-243.

Horigome, T., Kurokawa, S., Sawada, K., Kudo, S., Shiga, K., Mimura, M., & Kishimoto, T. (2022). Virtual reality exposure therapy for social anxiety disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 50, 2487-2497.

Nishikawa, Y., Fracalanza, K., Rector, N., & Laposa, J. (2022). Now I always have to perform well! Effects of CBT for social anxiety disorder on negative interpretations of positive social events. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 46, 1126-1136.

Raee, M., Fatahi, N., Sadegh Homayoun, M., Ezatabadipor, H., & Marzieh, S. (2022). The effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) on self-esteem, self-concept, and social anxiety of people with social anxiety disorder. Journal of Psychiatry, 23(5), 1-7.

Stefaniak, I., Hanusz, K., Mierzejewski,P., Bien ́kowski,P., Parnowski, T., & Murawiec, S. Preliminary study of efficacy and safety of self administered virtual exposure therapy for social anxiety disorder vs. cognitive-behavioral therapy. (2022). Brain Science, 12, 1236.

Yang, L., Zhou, X., Pu, J., Liu, L., Cuijpers, P., Zhang, Y.,…& Xie, Peng. (2019). Efficacy and acceptability of psychological interventions for social anxiety disorder in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 28, 79-89.

Citation

Youngdahl, J. (2022). Evidence-based treatment for social anxiety disorder in teens. Continued Psychology, Article 180. Available from www.continued.com/psychology.