Editor's Note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Racism and Mental Health, presented by Sophie Nathenson, PhD.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Identify two mechanisms by which mental health disparities exist by race.

- Describe three examples of institutional racism that influence mental health.

- Explain three clinical or policy-level interventions that address the impact of race and racism on mental health.

Risks and Limitations

This course does not contain a comprehensive summary of research on racism and mental health. It does not contain research specific to every minority group. All the data, including population and methods, is subject to change over time. Research in this presentation may refer to general patterns, but it does not represent any specific organization or set of individuals.

Roadmap

Here's the roadmap for today's discussion. First, I'll introduce the sociological perspective and its connection with the mental and behavioral health professions. Following that, I'll delve into the multifaceted definition of racism, examining its manifestations at three distinct levels: interpersonal, institutional, and cultural. Subsequently, I'll describe pivotal research findings on the connection between racism and mental health before concluding with a presentation of recommendations drawn from the psychology field aimed at combating racism.

Relevance for Mental Health Professionals

The relevance of this topic for mental health professionals traces back over half a century. While discussions surrounding the impact of racism and discrimination on mental health were undoubtedly occurring prior, it was in the 1970s that a notable surge of publications emerged from the psychology and psychiatry fields. These publications not only delineated the concept of institutional racism but also explained its profound effects on clients. Moreover, they offered actionable strategies and convened task forces dedicated to addressing these issues. A poignant excerpt from one such publication underscores the imperative for white psychiatrists to heighten their awareness of how their everyday practices unwittingly perpetuate institutional white racism within the realm of psychology. “We are asking white psychiatrists to become increasingly aware of how their everyday practices continue to perpetuate institutional white racism in psychiatry…a significant reduction in economic barriers to psychiatric care…relinquishing negative stereotypes” (Sabshin et al.1970). This served as a call to action to interrogate the often unseen external forces that shape clinical interactions and to integrate this awareness into professional practice.

Identifying societal-level factors, such as economic barriers, was of particular significance, which necessitated attention and remediation. One recent publication underscores the assertion that among “all sectors of healthcare, mental health is best equipped to stand against racism” (Mensah, Ogbu-Nwobodo, & Shim, 2021). This assertion transcends the traditional purview of client care, advocating for active engagement beyond the confines of clinical settings. This paradigm shift underscores the recognition that combatting racism requires understanding broader societal issues and a willingness to advocate for systemic change—an aspect I will delve into further.

The Sociological Perspective

I always begin with an exploration of the sociological perspective, as my background lies in medical sociology rather than mental and behavioral healthcare. In this field, our focus is on investigating the underlying social conditions and factors that contribute to health inequalities within society.

While psychology delves into the intricacies of individual differences—examining personal histories, behaviors, emotions, and biological makeup—sociology takes a broader lens, identifying disparities between groups. These groupings may be delineated by various criteria such as age, gender, race, employment status, marital status, or geographical location. It's crucial to note that within these social groupings, individuals are not homogenous; rather, we seek to understand the distinctions between them.

Within the realm of medical sociology, our gaze is fixed on health outcomes, seeking to decipher the societal undercurrents that might give rise to disparities. When we observe statistically significant differences in outcomes between groups, even after accounting for various individual factors, it signals a need to examine the social environment—a factor that may be influencing these divergences.

Racism, within this paradigm, is recognized as a potent social determinant of health, capable of exerting profound impacts on both physical and mental well-being. It's crucial to conceptualize race as a social construct rather than a biologically or genetically determined trait. In this context, being a member of a minority race does not necessarily denote numerical minority status but rather denotes a lack of dominance and may signify disparities in opportunities and power within society.

Within the sociological framework we are adopting today, we are attentive to the influence of social context alongside genetic, physiological, and psychological factors in shaping behavioral patterns and mental health disorders. It's essential to recognize that health outcomes and behaviors are multifaceted and influenced by a myriad of factors. While we focus on societal patterns and their correlation with experiences of racism and discrimination, we acknowledge the intricate interplay between psychology, physiology, genetics, and social dynamics—all of which contribute to the health outcomes. Today, we are zooming in on the societal factors, recognizing that they are but one piece of a complex puzzle.

The Power of Authority and Social Environment

There are a couple of studies that consistently come to mind when contemplating the profound influence of the social environment, particularly on a psychological level.

Stanley Milgram study

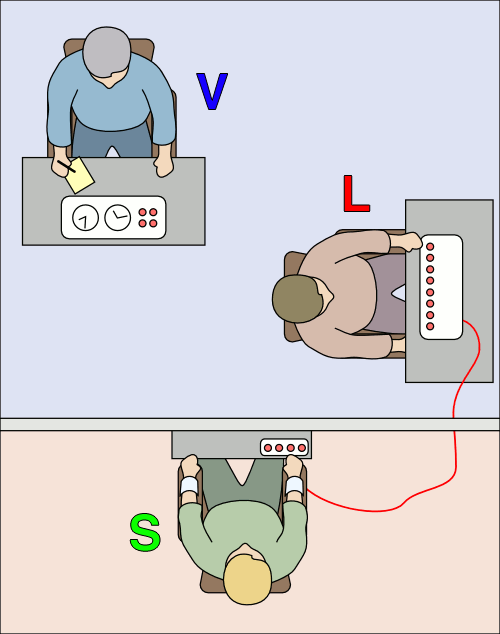

One of the most widely cited studies that underscores the potent influence of the social environment is the Stanley Milgram study, conducted in 1961. In this seminal experiment, participants were assigned roles: an experimenter (the authority figure, V), a teacher (L), and a learner (S).

Figure 1. Milgram experiment setup.

The setup, seen in Figure 1, involved the teacher posing questions to the learner, with incorrect responses resulting in purported electric shocks administered by the teacher. These shocks escalated in intensity, with the learner feigning distress and discomfort.

What emerged from this study was profoundly unsettling: individuals, when placed under the sway of authority, demonstrated a startling willingness to inflict harm. Participants, despite their initial reluctance, proceeded to administer shocks, some purportedly reaching levels of potential fatality. While the shocks were simulated, the implications were profound, revealing the extent to which authority figures can shape our thoughts and actions, coercing us into behaviors we might otherwise consider unthinkable.

Stanford prison experiment

Another landmark study that vividly illustrates the sway of the social environment is the Stanford prison experiment conducted in 1971. In this simulation, a cohort of college men was partitioned into two groups: prisoners and guards. What transpired within the confines of this simulated prison environment was both illuminating and disconcerting.

Remarkably swiftly, the guards assumed authoritarian roles, exhibiting behaviors that veered into aggression and abuse. While not all guards succumbed to this behavior, a significant proportion did, wielding their newfound power with alarming ease. Conversely, the prisoners swiftly adopted a passive and submissive demeanor; their resistance largely quelled in the face of the guards' dominance.

This rapid transformation underscores the profound impact of social roles, demonstrating how individuals, when thrust into specific roles within a structured social context, can quickly adopt behaviors that conform to the expectations associated with those roles.

Jane Elliot's blue eyes, brown eyes exercise

One of the most compelling demonstrations of the impact of social conditioning is the exercise conducted by teacher Jane Elliott in the aftermath of Martin Luther King Jr.'s assassination, an experiment often referred to as the "blue eyes, brown eyes" exercise. This exercise, conducted over two days, ingeniously exposed the malleability of attitudes and behaviors in response to social messaging.

On the first day, Elliott segregated her students based on eye color, with blue-eyed individuals designated as superior and brown-eyed individuals as inferior. Through subtle reinforcement of this hierarchy, she observed a rapid transformation in behavior: the "superior" group performed better on tests and exhibited discriminatory behavior towards their "inferior" peers. Remarkably, these attitudes and behaviors reversed on the second day when the roles were switched.

This experiment powerfully illustrates how societal messages and roles shape our cognition, behavior, and even academic performance. It highlights the impact of social environments on brain development and reinforces the notion that individual beliefs and attitudes can be strongly influenced by external factors.

These studies collectively underscore the interplay between individual psychology and the broader social context. They serve as reminders of the pervasive influence wielded by authority figures, societal roles, and messaging, shedding light on the mechanisms through which discrimination is perpetuated and its profound effects on individuals' lives, cognition, and behaviors.

Defining Racism

Racism, at its core, manifests as a social system underpinned by an ideology that categorizes one race as superior and others as inferior. Within our society, this hierarchy positions non-white individuals as inferior or as the "other," with different races invariably compared to the standard of whiteness. Even within the framework of cultural competency, which aims to enhance outcomes among minority populations, there persists a subtle implication of a dominant culture against which others are measured—a phenomenon closely linked to ethnocentrism, wherein one's own culture is held as the standard.

While it's natural to notice and compare cultural differences when encountering diverse communities, this tendency also reflects the influence of our socialization within a particular cultural milieu. As the famous anthropologist Ralph Linton noted, "The last thing a fish would notice would be the water"—our cultural norms and values are so ingrained that they often go unnoticed. These differing socialization processes give rise to cultural diversity and disparities within society.

Racism, however, extends beyond mere individual beliefs or behaviors; it encapsulates an overarching ideology that permeates various levels of societal organization. It manifests in multiple forms, ranging from interpersonal interactions to institutional practices and societal structures. This systemic nature of racism profoundly shapes the allocation of resources within society, influencing everything from laws and policies to workplace dynamics and individual interactions. Its influence is pervasive, impacting both explicit actions and the often unconscious biases that shape our thoughts and behaviors.

Historical Roots

Examining the historical underpinnings of racism reveals a fixation on physical characteristics as markers of racial difference. Scientists of the past endeavored to categorize humans based on these perceived differences, resulting in myriad classifications of race—a testament to the inherently subjective nature of such categorizations.

Racism, in its historical context, emerged as a mechanism to justify the exploitation of certain groups, particularly through the institution of slavery. By labeling these groups as inherently inferior, proponents of racism sought to rationalize their deprivation of basic rights and privileges. This process of othering contributes to the dehumanization of marginalized communities, effectively rendering them as less than equal in the eyes of the dominant group.

Scientific advancements have since debunked the notion of race as a genetically determined trait. Instead, research has underscored the vast genetic diversity within and between racial groups, highlighting the fallacy of using race as a biological marker of inherent difference. Despite this scientific understanding, the social significance of race remains potent, shaping societal structures and interactions in profound ways.

Health Disparities by Race

When examining health disparities by race, it's crucial to distinguish between health disparities and health inequities. A health disparity simply refers to differences in health status between groups, with race being one of the many social factors considered. These differences are identified through research that controls for individual factors and seeks to explain potential variables that may contribute to variations in health outcomes. Our social location—comprising both ascribed and achieved statuses—plays a pivotal role in shaping our experiences within society. Ascribed statuses are those inherent from birth, while achieved statuses are acquired over time through various accomplishments, such as educational attainment. These statuses collectively form our social location and serve as our starting points within societal hierarchies and organizations.

When investigating health disparities, the focus shifts from individual characteristics to group differences, aiming to understand the broader societal factors at play. It's not about assuming differences based on race but rather about identifying significant variations in health outcomes and exploring the underlying social determinants that may contribute to these differences. In essence, it's about contextualizing health outcomes within the broader socio-political landscape to discern their implications and inform targeted interventions aimed at promoting health equity for all.

Health inequities, unlike disparities, arise from systemic factors such as policies, practices, and access to resources, resulting in unjust and preventable differences in health outcomes. In the field of medical sociology, we often examine "amenable deaths" or excess deaths—those that could have been prevented with adequate resources and interventions. We can discern how legislative and systemic changes affect health outcomes by examining policies and comparing different regions.

These inequities manifest across various health indicators, including life expectancy, infant mortality, premature births, overall morbidity and mortality, and disparities related to COVID-19 infection and mortality rates. Even among populations with high socioeconomic status and healthy behaviors, such as non-smoking and proper nutrition, racial disparities persist, particularly in outcomes like premature birth rates.

The COVID-19 pandemic has starkly highlighted the intersection of health disparities and social determinants of health. Overlaid upon existing health conditions like COPD, diabetes, and obesity—which are more prevalent in marginalized communities—the pandemic has exacerbated health inequities. Social and economic factors such as poverty, stress, and social isolation further compound these disparities, creating a complex web of interconnected influences on health outcomes.

These disparities are not evenly distributed across populations but are concentrated in specific communities and neighborhoods with higher social and economic disadvantage levels. The confluence of these factors underscores the multifaceted nature of health inequities and the urgent need for comprehensive, multi-level interventions to address their root causes and promote health equity for all individuals and communities.

Mental Health Inequity

The persistence of mental health inequities is a concerning and disheartening reality, reflected in discussions and efforts within professional, scientific, and advocacy circles. In 2002, the Institute of Medicine issued a seminal report titled "Unequal Treatment," which documented the disparities in mental health outcomes by race. This report, alongside a wealth of prior research and longitudinal studies, has provided an extensive evidence base highlighting the significant differences in mental health experiences and outcomes that persist along racial lines.

While strides have been made in understanding and addressing mental health disparities, substantial gaps in data and research persist, hindering comprehensive efforts to tackle these issues effectively. Despite the accumulation of evidence, meaningful reductions in mental health disparities by race have yet to be realized, underscoring the complexity and resilience of these inequities.

The disparities in mental health treatment access and utilization among different racial and ethnic groups, as highlighted by SAMHSA surveys in 2020, are deeply troubling. The surveys showed that 69% of Black and 67% of Latinx adults were not receiving any mental health treatment if they were identified that they needed mental health treatment. In addition, 42% of Black and 44% of Latinx adults did not get any treatment for serious disorders. Also, 88% of Blacks and 89% of Latinx did not get any treatment for substance abuse disorders. White individuals had nearly twice the odds of receiving community-based mental health and substance use treatment, and that was four and a half times higher odds of receiving treatment for co-occurring disorders. The statistics reveal stark differences in treatment rates, with Black and Latinx individuals experiencing significant barriers to accessing mental health care compared to their White counterparts. These findings underscore the urgent need to address the systemic factors contributing to these disparities.

While race is a critical factor in understanding mental health inequities, it's essential to recognize that other intersecting identities, such as gender, gender identity, sexuality, disability status, and socioeconomic status, also play significant roles in shaping individuals' experiences of discrimination and access to care. Discrimination, whether based on race or other factors, creates social exclusion and can contribute to feelings of not belonging, exacerbating mental health disparities.

This broader lens allows us to understand mental health inequities as stemming from systemic factors embedded within various social institutions, including education, family, government, religion, and media. These institutions influence perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors collectively, contributing to social exclusion and disparities in mental health outcomes.

Addressing mental health disparities requires a comprehensive approach that recognizes the intersecting influences of race, identity, and social status. It entails dismantling systemic barriers, promoting inclusivity and belonging, and ensuring equitable access to culturally competent mental health care for all individuals. By addressing the root causes of mental health inequities, we can work towards building a more just and equitable society where everyone has the opportunity to thrive mentally and emotionally.

Social Determinants of Health

Now, let's delve into the realm of social determinants of health. These encompass various societal factors that operate at a level beyond the individual. At this juncture, our focus shifts to collective groupings underpinned by structural dynamics. When considering group statuses based on age, race, gender, disability, and education, we gain insights into the social underpinnings of health outcomes. These factors inform health disparities and serve as key social determinants.

Social determinants operate within the broader societal context and can manifest at various levels—whether at the neighborhood, city, or state level. This multifaceted environment provides diverse frameworks for understanding health disparities. Key among these determinants are issues such as food insecurity, housing instability, and socioeconomic status, which encompass factors like income, employment, and wealth. Additionally, community infrastructure—including transportation systems and sidewalks—plays a vital role in shaping access to healthcare and overall well-being.

Furthermore, the quality and accessibility of education, insurance coverage, and access to care are potential barriers influencing health outcomes. Adverse childhood experiences, along with issues of race and racism, also contribute significantly to health disparities.

Levels of Racism

There are three levels of racism: interpersonal, institutional, and cultural, which correspond to the micro, meso, and macro levels, respectively. The interpersonal level, specifically discrimination, receives the most attention in research. In the United States, our culture tends to prioritize individuality over collectivism. Consequently, studies often examine the experiences of individuals facing discrimination in various social settings, such as at home, school, work, or in the community.

Interpersonal Level

The interpersonal level of racism and discrimination is the most extensively studied, reflecting the individual-focused nature of American culture. Research in this area examines the experiences of discrimination on a one-to-one or one-to-many basis, occurring across various settings such as home, school, work, and community. Meta-analyses, which compile and analyze numerous studies, reveal that individual experiences of discrimination are associated with an increased risk of major mental disorders, lower life satisfaction, and diminished self-esteem. This highlights the interconnection between discrimination and mental health outcomes, underscoring the importance of considering broader contextual factors within the behavioral health fields.

Furthermore, experiences of discrimination can precipitate personality changes, such as heightened neuroticism, over time. This association persists even when accounting for individual factors, emphasizing the independent impact of discrimination experiences. Importantly, these negative effects accumulate over the life course, suggesting a compounding effect with prolonged exposure to discrimination.

Moreover, discrimination's impact can extend beyond the individual experiencing it, affecting others vicariously. For instance, witnessing a caregiver endure discrimination can evoke a response in individuals, influencing their mental health as well. This highlights the pervasive and far-reaching consequences of discrimination on both the body and mind, highlighting the urgent need to address systemic inequities to mitigate its detrimental effects.

Experiencing discrimination

Let’s talk about experiencing discrimination. Prejudice is making assumptions based on race. Discrimination encompasses actions stemming from prejudice, such as microaggressions, profiling, and stereotyping. Research suggests that a significant proportion of ethnic minorities—between 26 and 35%—have encountered discrimination, which correlates with adverse mental health outcomes. These include emotional distress, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, lowered self-esteem, and substance misuse. Moreover, discrimination is associated with adverse physical health outcomes, including high blood pressure, high body-mass index, poor overall health, and risky behaviors among adolescents.

Coping with social stressors like discrimination can lead to various coping strategies, some of which may have deleterious effects on health. Recognizing the link between social experiences and health outcomes is crucial in addressing the well-being of affected individuals.

Experiences of discrimination vary widely and affect diverse populations differently. Black and Latinx individuals tend to experience higher levels of discrimination compared to White or mixed-race Latinx individuals. This correlation often follows a socioeconomic gradient, similar to health outcomes. The significance of skin tone as a social determinant of discrimination underscores its arbitrary yet potent influence on individuals' experiences.

The stereotype of Asian Americans as a model minority can obscure disparities in mental health within this population. Despite the stereotype of high achievement, Asian adolescents report significant levels of discrimination, exacerbated by events like the COVID-19 pandemic and media-promoted stereotypes.

Meta-analyses demonstrate that experiences of racism are associated with an increased risk of traumatic stress symptoms, demonstrate the importance of acknowledging and addressing discrimination's impact on mental health. Incorporating this knowledge into practice can enhance support for individuals affected by discrimination, even if they do not explicitly raise the issue.

Impact on children

The impact of racism on children is significant, with both direct and vicarious experiences resulting in twice the risk of developing mental health problems such as anxiety, depression, suicide risk, and low self-esteem. Addressing this issue through interventions in education and media could substantially reduce this heightened risk and positively influence children's well-being and development.

Persistent experiences of racism can also significantly impact children's socioemotional and cognitive development. Studies have shown that children exposed to ongoing racism are twice as likely to experience sleep problems, which can adversely affect their school performance.

Research indicates that racism affects parenting styles and caregiver mental health, leading to a twofold increase in preterm births and disproportionately high rates of maternal mortality. Black women are 3.3 times more likely to experience maternal mortality than white women, and American Indian/Alaska Native women are 2.4 times more likely to experience maternal mortality.

Role of unconscious bias

As discussions around racism become more prevalent in society, it's critical to address the concept of unconscious bias. This form of bias operates implicitly and outside conscious awareness, making individuals unaware of its influence. Despite not identifying with discriminatory behavior, unconscious bias can significantly impact the quality of care provided, particularly in healthcare settings.

Evidence shows distinct racial disparities in psychiatric diagnoses, highlighting the pervasive nature of unconscious bias. For instance, studies reveal that Latinos are more frequently diagnosed with anxiety, while African Americans are more commonly diagnosed with mood disorders, even when presenting identical symptoms. These discrepancies spur a need for greater awareness and mitigation of unconscious biases in clinical practice.

The intersection of racism with other social factors exacerbates its adverse effects on mental health outcomes. For instance, research indicates that Black veterans experience higher levels of pain, with discrimination experiences serving as a mediator for this association. In other words, the more discrimination they encounter, the worse their pain levels become, compounding the impact of racism on mental well-being.

Institutional Level

At the institutional level, the focus shifts to federal and local policies and social systems that disproportionately impact certain groups. Unlike individual or interpersonal racism, structural racism is rooted in power structures that extend beyond individual actions.

Structural factors, such as those observed at the community level, encompass the social determinants of health. These conditions represent inherent characteristics of society itself, including aspects like access to resources, economic opportunities, and social support networks.

Structural racism

Structural racism, as defined by the Aspen Institute, describes “a system in which public policies, institutional practices, cultural representations, and other norms work in various, often reinforcing ways to perpetuate racial group inequity.” This concept encompasses the historical and cultural dimensions that have allowed privileges linked to whiteness to persist over time while also perpetuating disadvantages associated with race. It's important to acknowledge that social determinants can affect various populations, including white communities, and that privileges associated with whiteness do not always translate to universal benefits. Discrimination can occur across multiple social statuses, including gender, gender identity, age, and socioeconomic status, complicating the dynamics of privilege and disadvantage.

However, structural racism primarily examines differences in resource allocation and the social status assigned to minority racial groups. It refers to the existence of overarching societal structures that influence individual thoughts and attitudes, ultimately shaping access to mental health services.

Structural factors

Structural factors include:

- Immigration policies

- Residential segregation (controlling for socioeconomic factors)

- Mass incarceration; relationship to adverse childhood experiences

- Institutional racism and sexism, historical and contemporary

- Neighborhood disadvantage, poverty, unemployment

- Displacement and loss of culture/belonging

- Social capital and social cohesion

- Redlining (reduced investment); services (schools, hospitals); built environment

Structural factors encompass wide-ranging societal elements such as immigration policy, residential segregation (accounting for socioeconomic factors), mass incarceration (linked to adverse childhood experiences), and historical institutional racism and sexism. Neighborhood disadvantage, particularly displacement, significantly contributes to poor mental health outcomes, as does substance abuse and overdose rates within communities. Social capital and cohesion, indicative of community connectedness, also play pivotal roles. Redlining, a discriminatory practice barring minorities from mortgage access, which persisted from 1934 into the 1960s, further exacerbates disparities.

Delving deeper into these factors, anti-immigrant immigration policies can have profound psychological impacts on minority populations, fostering racialized exclusion and undermining individuals' sense of belonging. This sense of belonging holds paramount importance for mental health, rooted in our evolutionary history, where social ostracization posed grave survival risks. Thus, these examples underscore the profound influence of broader social environments on individual mental health.

Residential segregation, the spatial separation of individuals based on race within neighborhoods and communities, can be enforced by law or perpetuated through individual discriminatory practices. Examples include redlining, differential mortgage rates, and disparities in homeownership opportunities. The phenomenon extends to the relocation of workplaces from inner-city areas to suburban locales, contributing to mass unemployment and subsequent social upheaval. White flight, observed predominantly during the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, further exacerbated these trends, leading to the fragmentation of communities.

The historical context is key when understanding these dynamics. Laws and policies have systematically entrenched disparities in wealth and resource access, resulting in vastly different starting points for various racial groups in their pursuit of health and well-being. The repercussions of such disparities, compounded over time, manifest in enduring social and economic inequalities. Recovery from such setbacks, compounded by the profound mental and physical health impacts of unemployment and poverty, often spans generations and hinges on policy reform.

Empirical research underscores the significance of residential segregation, revealing its substantial predictive power. Studies suggest that eliminating residential segregation could markedly influence socioeconomic indicators, potentially reducing single motherhood rates by two-thirds among different racial groups. These findings demonstrate the impact of historical and systemic factors on contemporary societal disparities and highlight the imperative of addressing structural inequities to foster meaningful change.

The phenomenon of incarceration reflects systemic inequalities, with Black and Latinx populations disproportionately represented within the criminal justice system. As prisons increasingly assume roles as mental health care providers, the ramifications extend beyond incarceration itself. Individuals with a history of arrest are more likely to experience major depressive disorder, while aggressive policing correlates with declines in mental health. These circumstances can contribute to adverse childhood experiences, further compounding mental health risks, particularly within minority populations already burdened by structural inequities.

Neighborhood disadvantage amplifies these disparities, serving as a microcosm of broader societal injustices. Areas characterized by concentrated poverty exhibit heightened levels of social stress and safety concerns across multiple dimensions, encompassing physical, chemical, and psychosocial domains. The ripple effects are profound and include diminished property values, disinvestment, and shifts in local commerce, such as the transformation of essential services like restaurants and grocery stores into establishments that may pose health risks, such as tobacco shops. This economic decline perpetuates a cycle of deprivation, increasing challenges faced by residents and deepening health inequities within marginalized communities.

Socioeconomic factors play a significant role in shaping disparities, with historical practices like redlining significantly impacting the wealth accumulation of different demographic groups. Whites, for instance, have a net worth ten times higher than their counterparts. The enduring legacy of social exclusion perpetuates intergenerational wealth disparities, underscoring the need to challenge ingrained assumptions at the individual level while acknowledging this contextual backdrop.

It's important to recognize that structural inequities affect all demographics, with consequences reverberating throughout society. Stereotyping and stigmatization, exemplified by the rejection of initiatives like the Affordable Care Act, exacerbate mortality rates and hinder access to preventive care, even among privileged groups.

Developing structural competence is paramount in navigating these complexities. It entails discerning how upstream social determinants of mental health influence downstream clinical outcomes, illuminating the pervasive impact of historical injustices. For instance, the pathologization of normal responses to trauma, such as the portrayal of the desire to escape slavery as a disease, has entrenched systemic racism and biased diagnostic practices, perpetuating disparities across generations.

Recognizing the limitations of existing classifications and diagnoses is essential, as they often fail to capture the systemic factors underpinning mental illness, underscoring the imperative for a more holistic understanding of mental health within its broader sociohistorical context.

Cultural Level

At the cultural level, pervasive stereotypes perpetuated through media and societal norms can profoundly impact individuals' self-esteem and sense of identity. The looming threat of being stereotyped or subjected to discriminatory treatment can impede effective communication with healthcare providers, exacerbating disparities in access to care. While not universally experienced, these cultural phenomena reflect deeply ingrained societal ideologies and have far-reaching implications, influencing policy decisions and shaping interpersonal interactions. Derogatory terms and discriminatory practices underscore the harmful consequences of cultural stereotypes, as evidenced by the stigmatization experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Moreover, emerging research in epigenetics sheds light on how interpersonal and structural racism can manifest in physiological changes, transcending generations. Traumatic experiences and environmental factors can modulate gene expression, illustrating the intergenerational impact of social environments on physical health. Consider your grandmother's social environment: Did she face poverty, discrimination, or domestic violence? These stressors can leave a lasting imprint, affecting her and subsequent generations. Additionally, there are immunological implications; stress can impact the immune system, compounding the effects across time.

Fortunately, there are protective factors at play. Social support, community cohesion, religious or spiritual practices, and grassroots organizing can all mitigate the impact of discrimination. While they may not eliminate its effects entirely, these factors contribute to positive self-perception and facilitate meaningful social connections, fostering resilience in the face of adversity.

Policy Recommendations

As we delve into actionable recommendations, let's reflect on our sociological exploration. From the outset, we acknowledge that mental health conditions manifest disparately across populations, shaped by social and historical contexts. Our journey led us to confront structural racism—a pervasive force that continues to influence societal structures.

To address this, we advocate for structural competence—a deep understanding of how systemic factors influence individual interactions. Consider, for instance, a clinician encountering a patient who exhibits signs of distress. Understanding the broader social context—such as the impact of discrimination—can profoundly alter the approach to care, fostering empathy and trust.

At the systemic level, alongside policy reforms, we urge increased research into the impact of racism on psychiatric care and disorders, particularly among minority populations. For instance, exploring how discriminatory practices may skew diagnoses, such as Latinos being diagnosed with anxiety more frequently than African Americans for the same symptoms, is imperative.

To effect change, we propose diversifying the recruitment and mentorship of clinicians, ensuring that mental health services are accessible and culturally competent. This might involve advocating for essential services like interpreters, which are crucial for effective communication in diverse communities. Integrating structural competency and anti-racist principles into educational curricula and cultural competency training is critical. These measures are crucial for fostering equitable mental health care and combating the insidious effects of structural racism.

Practice Recommendations

At the clinical treatment level, psychologists and psychiatrists play a key role in addressing collective trauma and understanding how external factors impact individuals. Increasing awareness and acknowledging the influence of systemic issues on mental health, as well as the fact that racism exists everywhere, is a vital first step. Taking an honest inventory of one's social environment and applying a racial equity lens can guide practitioners in providing more inclusive and effective care.

Recognizing the impact of societal and historical factors on psychology, genetics, behavior, and mental health systems is essential. It's not just about understanding the psychological effects but also acknowledging the physiological toll—such as increased cortisol production and accelerated physical deterioration—that racism can induce.

By acknowledging these systemic issues, clinicians can engage in constructive conversations with their patients and communities, fostering awareness and understanding. They may also choose to advocate for change at the policy level or become involved in community initiatives.

While addressing racism in mental health care may present challenges, it also offers an opportunity for personal growth and professional development. Practitioners who have experienced racism firsthand may bring valuable insights to their work, enhancing their ability to provide empathetic and culturally competent care.

References

American Psychological Association. (2020, May 29). ‘We are living in a racism pandemic,’ says APA president [Press release]. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2020/05/racism-pandemic

Anglin, D. M., Lighty, Q., Yang, L. H., Greenspoon, M., Miles, R. J., Slonim, T., Isaac, K., & Brown, M. J. (2014). Discrimination, arrest history, and major depressive disorder in the US Black population. Psychiatry Research, 219(1), 114-121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.05.020

Aspen Institute. (2016, July 11). 11 terms you should know to better understand structural racism. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/blog-posts/structural-racism-definition/

Bailey, Z. D., Krieger, N., Agénor, M., Graves, J., Linos, N., & Bassett, M. T. (2017). Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet, 389(10077), 1453–1463. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X

Berry, O. O., Londoño Tobón, A., & Njoroge, W. F. M. (2021). Social determinants of health: The impact of racism on early childhood mental health. Current Psychiatry Reports, 23(5), 23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-021-01240-0

Cénat, J. M. (2020). How to provide anti-racist mental health care. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(11), 929-931. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30309-6

Cogburn, C. D., Roberts, S. K., Ransome, Y., Addy, N., Hansen, H., & Jordan, A. (2024). The impact of racism on Black American mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry, 11(1), 56-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(23)00361-9

Hammet, P. J., Eliacin, J., Saenger, M., Allen, K. D., Meis, L. A., Krein, S. L., Taylor, B. C., Branson, M., Fu, S. S., & Burgess, D. J. (2024). The association between racialized discrimination in health care and pain among Black patients with mental health diagnoses. The Journal of Pain, 25(1), 217-227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2023.08.004

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Prins, S. J., Flake, M., Philbin, M., Frazer, M. S., Hagen, D., & Hirsch, J. (2017). Immigration policies and mental health morbidity among Latinos: A state-level analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 174, 169-178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.11.040

Heard-Garris, N. J., Cale, M., Camaj, L., Hamati, M. C., & Dominguez, T. P. (2018). Transmitting trauma: A systematic review of vicarious racism and child health. Social Science & Medicine, 199, 230-240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.018

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Smedley, B. D., Stith, A. Y., & Nelson, A. R. (Eds.). (2003). Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. National Academies Press (US).

Liu, S. R., & Modir, S. (2020). The outbreak that was always here: Racial trauma in the context of COVID-19 and implications for mental health providers. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(5), 439. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000784

Maglo, K. N., Mersha, T. B., & Martin, L. J. (2016). Population genomics and the statistical values of race: An interdisciplinary perspective on the biological classification of human populations and implications for clinical genetic epidemiological research. Frontiers in Genetics, 7, 22. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2016.00022

McGregor, B., Belton, A., Henry, T. L., Wrenn, G., & Holden, K. B. (2019). Improving behavioral health equity through cultural competence training of health care providers. Ethnicity & Disease, 29(Suppl 2), 359. https://doi.org/10.18865/ed.29.S2.359

McIntosh, K., Moss, E., Nunn, R., & Shambaugh, J. (2020, February 27). Examining the black-white wealth gap. Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/examining-the-black-white-wealth-gap/

Ogedegbe, G. (2020). Responsibility of medical journals in addressing racism in health care. JAMA Network Open, 3(8), Article e2016531-e2016531. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.16531

Paradies, Y., Ben, J., Denson, N., Elias, A., Priest, N., Pieterse, A., Gupta, A., Kelaher, M., & Gee, G. (2015). Racism as a determinant of health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One, 10(9), Article e0138511. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138511

Pestaner, M. C., Crumb, L., Crowe, A., & Cuthrell, K. C. (2024). The role of protective factors in moderating the association between racism and suicidal ideation or depression among rural Black youth: A scoping review. Youth & Society, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X231222032

Petersen, E. E., Davis, N. L., Goodman, D., Cox, S., Mayes, N., Johnston, E., Syverson, C., Seed, K., Shapiro-Mendoza, C. K., Callaghan, W. M., & Barfield, W. (2019). Vital signs: Pregnancy-related deaths, United States, 2011- 2015, and strategies for prevention, 13 states, 2013-2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(18), 423–429. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6818e1

Polanco-Roman, L., Ebrahimi, C. T., Satinsky, E. N., Benau, E. M., Martins Lanes, A., Iyer, M., & Galán, C. A. (2024). Racism-related experiences and traumatic stress symptoms in ethnoracially minoritized youth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2023.2292042

Sanchez, D., Carlos Chavez, F. L., Capielo Rosario, C., Torres, L., Webb, L., & Stoto, I. (2024). Racial differences in discrimination, coping strategies, and mental health among US Latinx adolescents during COVID-19. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 53(1), 114-128. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2024.2301762

Savell, S. M., Womack, S. R., Wilson, M. N., Shaw, D. S., & Dishion, T. J. (2019). Considering the role of early discrimination experiences and the parent–child relationship in the development of disruptive behaviors in adolescence. Infant Mental Health Journal, 40(1), 98-112. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21752

Schouler-Ocak, M., Bhugra, D., Kastrup, M. C., Dom, G., Heinz, A., Küey, L., & Gorwood, P. (2021). Racism and mental health and the role of mental health professionals. European Psychiatry, 64(1), Article e42. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.2216

Shepherd, C. C. J., Li, J., Cooper, M. N., Hopkins, K. D., & Farrant, B. M. (2017). The impact of racial discrimination on the health of Australian Indigenous children aged 5–10 years: Analysis of national longitudinal data. International Journal for Equity in Health, 16(1), 116. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-017-0612-0

Shim, R. S. (2020). Mental health inequities in the context of COVID-19. JAMA Network Open, 3(9), Article e2020104. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.20104

Singh, S. P. (2019). How to serve our ethnic minority communities better. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(4), 275-277. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30075-6

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018). National survey on drug use and health: Hispanics, latino or spanish origin or descent. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt23249/4_Hispanic_2020_01_14_508.pdf

Tavernise, S., & Oppel, R. A., Jr. (2020, March 23). Spit on, yelled at, attacked: Chinese-Americans fear for their safety. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/23/us/chinese-coronavirus-racist-attacks.html

Wallace, S., Nazroo, J., & Bécares, L. (2016). Cumulative effect of racial discrimination on the mental health of ethnic minorities in the United Kingdom. American Journal of Public Health, 106(7), 1294-1300. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303121

Wang, Y. (2024). Asian American adolescents' behavioral health within the context of racism, discrimination, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Adolescent Health, 74(2), 218-219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2023.10.019

Citation

Nathenson, S. (2024). Racism and mental health. Continued.com, Article 266. Available at www.continued.com/social-work