Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Understanding Trauma Part 1: What It Is and How It Shows Up, presented by Nicole Steward, MSW, RYT.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Define trauma, the different types of trauma, and trauma’s impact on our health.

- Explain (simply) the three-part brain model and each level’s attributes.

- Identify the ways trauma impacts social work practice.

Introduction

I am going to present Understanding Trauma. This is a two-part series. This first part talks about what trauma is and how it shows up.

Why Trauma?

First, I want to start by just saying why trauma? We know that young people from five to 18 are in school, therefore that is the most impactful place for us to find data and statistics. The National Child Trauma Stress Network says that one out of every four children attending school has been exposed to a traumatic event that can affect learning and/or behavior.

What is Trauma?

Trauma is very simple and complicated at the same time. Trauma is a deeply distressing or disturbing experience. It can occur once, it can occur multiple times, and it can occur at any stage in our lives. It is an experience that is overwhelming to our system.

Miriam-Webster Dictionary defines it (trauma) as a disordered psychic or behavioral state resulting from severe mental or emotional stress or physical injury.

I think it's also important to remember the root of the word. The root of the word trauma means “wound”. As social workers, we know that most of the folks that we serve are showing up with some level of a wound, some level of trauma, so it's really important for us to really understand it.

Types of Trauma

There are a few different types of trauma and I think this is where the nuance comes in. I talk about big “T” and little “T” trauma. Not to minimize any trauma but recognizing that trauma shows up in different ways. Types of trauma include:

- Acute

- One-time traumatic event

- Chronic

- Multiple, different traumatic events

- Complex

- Ongoing, repeated trauma

- System-Induced

- Exposure to traumatic systems

The first type of trauma is acute trauma, which is a one-time traumatic event. For example, I have a friend who recently was at a retreat and twisted her ankle, actually broke her ankle at that retreat and she described that as an acute traumatic event, a one-time event. Acute trauma can happen at any stage in our lives.

The next type of trauma is chronic trauma. Chronic trauma is when we experience multiple traumatic events but those are different events. So maybe we break a bone, maybe we are in a car accident, maybe we experience being a victim of a crime; different traumas but multiple within our lifespan.

Then there's complex trauma. This may be one that many of us in child welfare or in public education work with often. Complex trauma is when the traumatic event is ongoing and repeated and potentially the same trauma. This is where child abuse comes in and fits in as complex trauma. You know, when a child is in a home or in a family where they are constantly being traumatized; whether it's physical abuse, emotional abuse, or sexual abuse. Complex trauma can also be war; when a soldier or someone in the military has to go into war, after war, after war for a long period of time, the same traumatic event.

And then there is system-induced trauma. This type of trauma is kind of a newer one but it's really important for us as social workers to keep it in our minds. What this means is exposure to traumatic systems. And ultimately what that means as many of our systems intend to do well or to do good by us; whether it's our healthcare system, our education system, our criminal justice system, the foster care system; they're intended for good but they may have unintended negative consequences or even traumatic impacts. An example might be the way we do discipline in public education. Now that's shifted a lot because many of us as social workers have come to the table and said this is a little traumatic. But when we push kids out, when we expel or suspend kids and push them out of school and tell them they have to be at home for a period of time, that can be traumatic to a child who is constantly being rejected and feels as though they're being pushed away and told that we don't want them in school. So, it's things like that that we just have to be aware of as members of systems, as social workers.

What is the Impact of Trauma?

I really appreciate Judith Herman's work. She has a book called "Trauma and Recovery", it's a great book to read, it's really intense and heavy but a good one for us social workers to have under our belts. And what she says is, "Traumatic events overwhelm the ordinary systems of care that give people a sense of control, connection and meaning."

What she says is that control, connection, and meaning are the things that make us human. That's what makes us different from our primate ancestors. The fact that we have a sense of control of some aspects of our lives, the feeling that we have a level of connection to the people in the world around us, and that we have some meaning.

When we wake up in the morning, we feel like there’s a reason to wake up and get out of bed and go and do our work or live our lives. And when we experience a traumatic event it shakes all of those foundations, so we feel like we are out of control, we have lost connection either because we feel like we can’t stay connected to certain people because it’s not safe or because maybe when a traumatic event happens some people tend to move away from us because they don’t want to deal with the discomfort of that trauma or the impact of that trauma. And then sometimes we lose our sense of meaning when we experience a traumatic event. What is this world? Why am I here? What’s the purpose of life? So, I think this is a really succinct definition of the impact of trauma.

Traumatic Situations

There are a plethora of ways and situations in which we can experience trauma. This is certainly not an exhaustive list but this is a list of some of the ways that we know folks are traumatized:

- Bullying

- Community violence

- Poverty/Homelessness

- Physical or Sexual Abuse

- Abandonment or neglect

- Acts of threats of terrorism

- Natural disasters/Pandemic

- Witnessing domestic violence

- Migration/Refugee experience

- The death or loss of a loved one (or pet)

- Medical trauma (own or that of a family member)

I have added pandemic to this list. We are recording this in April of 2020 while we are all in-home quarantine due to the COVID-19 virus. And this is a global trauma, this is an experience that many of us are realizing we are not in control of.

We may have lost a little bit of connection to the life that we knew before or the people in our environments that we used to be able to connect with very closely. And we might even have a little bit of a loss of sense of meaning especially for those of us who identify very strongly with our work and we can't be doing that right now. So, it's really important to recognize that we are currently experiencing a trauma. And any of these other things that are listed are also traumatic.

Now you may have experienced something on this list and feel like it wasn't that traumatic for you and that's what I meant when I said big “T” and little “T” trauma. We can all experience the same kind of traumatic event and it be seen as a traumatic event and not be fully impacted by that event.

I will talk a little bit later about protective factors and why some people are impacted more than others. It is not about personal weakness, it's about the fortification of our resilience. So that's where we as social workers come in and that's our role in undoing some of this trauma. But by just taking a look at this list recognizing, again it's not exhaustive and things that may have not been traumatic for you might be for the next person.

This is also a really good reminder that we have to validate everybody's trauma because you may have experienced something and it wasn't a big deal but the person sitting next to you experienced the same thing and it was overwhelming for their system.

What is the Impact of Trauma?

Again, the impact of trauma is really important when we think about development and again many of us as social workers whether we're in child welfare or not we might be working with an adult population or even an elderly population but we know that these things all come back to developmental stages. So, it's really important that we recognize that developmental trauma negatively impacts the social, emotional, and cognitive or neural development in a person. We are normally talking about birth to about age five when we talk about developmental trauma.

We could even go back and say prenatal to five if we want to talk about epigenetic or generational trauma. But it's really important that we remember that infants depend on their caregiver for their basics:

- survival

- warmth and love

- protection and safety

- emotional modulation

For basic survival we seek our caregiver, we seek warmth and love from that caregiver and we certainly seek protection and safety. Now one of the things that we seek from our caregiver is emotional modulation. Recognizing that when something scares a baby they look to their caregiver to see should I really be scared am I not safe or am I just having a really brief reaction but I look at you and you tell me everything's okay and I know I'm safe and my nervous system can regulate? As you can imagine it's important for infants to have that kind of a caregiver but not everybody does.

Developmental Trauma

I really appreciate this quote from Dr. Robert Stolorow, he says, "One consequence of developmental trauma relationally conceived, is that affect states take on enduring, crushing meanings. From recurring experiences of malattunement, the child acquires the unconscious conviction that unmet developmental yearnings and reactive painful feeling states are manifestations of a loathsome defect or of an inherent inner badness."

What this quote gets at is that when there is disorganized or dysregulated attachment when that caregiver isn't responding to that child and helping that child modulate their emotions, children and infants especially. They're very self-centered, they are the center of their universe as they must be for survival. And when those needs aren't met the only option for them to understand it is to make it about themselves and make it about their own defects or inability to be loved. That is the work that many of us social workers have to undo to depersonalize the traumatic experiences that many of those that we serve had in the past from who they are now in their sense of self-worth and self-esteem.

That's why self-esteem is such an important topic and I know when we start to talk about self-esteem we can get some eye rolls. But self-esteem comes from an adequate attachment and childhood, knowing that you are worthy of love and you are worthy of care and attention.

Chronic & Developmental Trauma

Chronic trauma interferes with the neurobiological development of a child and their capacity to integrate the sensory emotional and cognitive information. As we go through our lives, we're getting information from our environment and from the people in our environment constantly. And when we have a healthy nervous system, we can integrate what we're hearing, what we're feeling, what we're tasting, the temperature in the room, the behavior coming from other people, and the words other people are speaking; we can kind of pull all that together into a cohesive whole. If we experience chronic trauma (and remember a chronic trauma is different traumas but multiple traumas over the time) that impacts our neurobiological development and it almost makes our nervous system incapable of integrating the inputs in our environment.

Developmental trauma sets that stage for an unfocused response to subsequent stress. So, what happens is when we experience developmental trauma over our lifespan it becomes really challenging for us to integrate and to be able to focus on the modulated emotional response from any inputs. It's interesting that developmental trauma can lead to increases in the use of medical, correctional, social, and mental health services.

Again, this is the work we do as social workers. We are undoing developmental trauma all the time whether you work with elders, infants, school-age children, or you work in a college or you work in corrections. We are undoing developmental trauma.

Impact of Developmental Trauma

Some of the impacts of developmental trauma include:

- altered schemas of the world

- disturbed attachment patterns

- complex disruptions of affect regulation

- aggressive behavior against self and others

- failure to achieve developmental competencies

- anticipatory behavior and traumatic expectations

- loss of bodily regulation around sleep/food/self-care

- rapid behavioral regressions/shifts in emotional states

- multiple somatic problems (gastrointestinal distress to headaches

- lack of awareness of danger, resulting in self endangering behaviors

- self-hatred and self-blame and the chronic feelings of ineffectiveness

These are the impacts that many of us are mitigating with our clients and those we serve. When someone is impacted with developmental trauma their schema of the world, their way of thinking about how the world operates and trusting that it will operate in that way consistently gets altered. Their caregiver was not consistent. The care and love that they got, and the support and the warmth and love that they got and emotional modulation wasn't there. So why would they trust that the world would be what it is or what it says it is?

These are disturbed attachment patterns. Attachment issues from childhood can expand into our adult lives, they can impact our romantic relationships, they can impact our professional relationships.

Disruptions of affect regulation. Affect regulation is really important. When someone says something funny, are you laughing at it or are you angry? Like what does your face look like when you are experiencing that thing? Many of us if you've been in social work a long time, when you work with folks who experience trauma at least in my experience. I can be sitting across from someone and they're relating a very traumatic and overwhelming experience to me while laughing about it. A very different effect than I might expect from someone who may not be traumatized. And this actually happens a lot for me when I work with foster youth.

I'm a foster parent so I have three wonderful kids, they're all older now, they're 25, 26 and 27 but my 27-year-old is back with me. And I noticed that when he tells me stories of his childhood and kind of wants to relive those, he's telling me horrible stories of abuse but he's laughing the whole time. His affect regulation is just a little bit off.

We might find folks who experience aggressive behavior either towards themselves or toward others. Inability or failure to achieve developmental competencies. This is when we notice that we're working with someone who might be college-age but their ability to regulate or their ability to really understand things is at a younger age level. There may be also anticipatory behavior and traumatic expectations. So, this is when, you know, young people or whoever we're working with expects us to be mean to them, expects us to yell at them or curse at them or cancel an appointment. What that might actually look like though in our work is that if we have to cancel an appointment with a client or someone we're serving because of something really benign, right? Maybe we just have to take our dog to the vet so we have to reschedule that appointment, they might take that as, "Oh see, that she doesn't want to be with me, I'm a loser, I'm useless. Of course she doesn't want to help me, of course she's canceling this." And it becomes a bigger issue for them than just a canceled appointment. It's an expectation that there is more behind that.

There can also be a loss of bodily regulation specifically when we're talking about self-care. The inability to feed themselves or get good rest or sleep. Hygiene can become an issue. We also will notice rapid shifts in their emotional states and this may or may not be something that's diagnosable. It may not be a bipolar disorder or some kind of schizophrenia or anything related to pathology. It may just be that inability to modulate their emotions because again they didn't get that from the caregiver and if we aren't teaching that in schools or we're not sharing that with our clients they have no tools to do that. So, their emotional states may shift, they might have some levels of regression in their behavior as well.

Multiple somatic problems. This one I think is really important especially, you know, someone who works with school-aged children we often see stomach aches or headaches that may not have any medical diagnosis or medical grounding, that's what we call somatic. It's still in the body, they are still experiencing that pain or that issue, there just may not be any medical explanation for it. This is really important because this may be one of the first tells that a young person or an older person is trying to relay to us that they might be experiencing some level of trauma.

I find a big one is lack of awareness of danger. When kids have developmental trauma or they've experienced developmental trauma their ability to sense danger is a little bit compromised partly because they've been experiencing that danger from, again maybe, a caregiver or in their home and that's normal. So, when they are outside of the home or in a different environment their ability to know when something is about to happen or to sense danger either for themselves or if they have a young child with them. That can be challenged and compromised. Again, I've seen this with the young people I've worked with in foster care especially the young mothers that I've worked with. That sometimes their inability to see the dangers to themselves may shift when they have a child and then they are able to see danger related to that child, hopefully, right? That's where we want them to be.

And then this last one I think is, again is really important and this is a lot of the work that we do as social workers. Developmental trauma can cause self-hatred and self-blame or chronic feelings of ineffectiveness and this comes directly from those who are traumatizing us, right? They may tell us very directly, "This is your fault.” "I wouldn't do this but I have to because you've done this." "If you didn't do this I wouldn't have had to do that." Those are all lies, absolute lies around trauma. The victim is never ever at fault or the cause of trauma but that causes us to kind of internalize and self-blame especially when we're not getting any messages to the contrary. Unless someone is stepping in to stop that trauma and to say this is not right, you don't deserve this and this is not your fault the impact is long-term. Again, that is the beautiful work that we as social workers get to do is to remind those that we serve that this trauma is not theirs to hold.

Attachment Theory

And then we get to attachment theory. I'm not going to go too far into attachment theory, that's a whole other course we could pull into for another hour. But I really want us to remember attachment theory as a kind of grounding and a routing of our work. Attachment is a deep and enduring emotional bond that connects one person to another across time and space, that's such a beautiful way of explaining it, and especially now when we are quarantined and we're all kind of separated from those that we love and those that we normally have contact with.

Some of us notice this attachment is really strong, we might be able to still feel that that emotional bond to those that we can't quite be in the same space with. And this happens again in childhood. This is happening from birth to age five where we're getting that understanding of how we are attached to those that are caring for us. When an attachment is in children it's seeking a connection to a caregiver whenever they are upset or threatened. When a child cries, the hope is that a caregiver will be attentive to them. Now those of you who have toddlers you know that this doesn't mean that any time your child cries you give them what they want, it's anytime they cry you give them the attention that they need, right? You focus your gaze at them, you try to figure out what's happening. Now if your child is crying because they want, you know, another bowl of ice cream you're not going to necessarily give them that ice cream but you are going to attend to that need, right? You can turn to them and say, you know, I know you're really upset because you really want that bowl of ice cream but not tonight, we can have another bowl tomorrow after dinner. But you're giving that child that level of attachment, that level of care so that they know that their cry is listened to and heeded.

It's the same when we're trying to sleep train a baby. I've had the pleasure of having two of my foster daughters live with me when they had babies for the first two years of those babies' lives. And I got to do nighttime duty while they were working or in school. So it was one of those things where yes, I put them down and then I'm going to hear a cry and I'm going to go into the room, I'm going to be attentive to that cry but I'm not going to get them out of the crib and where it's not playtime at midnight, right? They know that they are cared for, they know that their cry or their seek for attention will be managed and they know that they're safe but they may not get what they want, right? That's very different.

When we look at attachment in adults that may be responding sensitively and appropriately to that child's need. So again, attachment is so important for the work we do as social workers because it's a generational thing. When we are working with mothers, you know, when my daughters were living with me, I was very much paying attention to what they needed from me as a parent but I was also watching how they engaged with their babies, and their ability to respond sensitively and appropriately when their babies needed them. There were some challenges, some of it was “why are you crying, I'll give you something to cry about,” which is not good attachment. But eventually, with the right modeling it was, “okay, I see now that I need to be attentive to the crying even if I don't give the baby what they need or what they want in that moment.” I'm going to give them what they need which is my attention. And that's when infants know how to regulate their system. If I cry like this, this is what I get, if I make no noise I won't get anything. Or I do know that someone will come, someone will see me, I'll get soothed a little bit. So, attachment is so important, and again this is its own workshop so we'll move along.

Trauma and the Brain

I really want to expand a little bit on the brain. And it's really important that we understand how trauma shows up in the brain for those we serve but it's also really important for us to recognize this as well. In part two we'll talk a little bit more about our own trauma as social workers, we're not getting away from that. But recognizing when I go through these parts of the brain, what I'd like you to do is really think about your own childhood and your own situation as well as maybe choosing one or two of your clients or those folks that you serve to think about as we talk about the brain and its development.

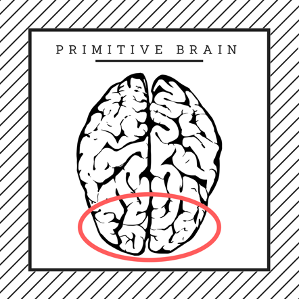

Reptilian Brain

Figure 1 is an image of the reptilian brain:

[Figure 1]

The reptilian brain is the base of the brain stem. It's the cerebellum and the brain stem. And if we remember from biology 101 in high school, our central nervous system is the brain and the spinal cord, right? That's the central nervous system. That's a two-way communication from the body to the brain and brain to the body. Our reptilian brain is the cerebellum and the brain stem that attaches directly to the spine. This is the part of our brain that is on autopilot. You all are sitting here, you're breathing, you're blinking, you're swallowing, the reproductive organs are working, your digestive organs are working, right? Everything is working in your body without you having to direct it. You don't have to sit here and go, breathe, blink, swallow, breathe, blink, swallow, breathe, blink, swallow, right? Your brain stem and cerebellum are taking care of all of that regulation for you.

The challenge is if we experience any injury to this part of the brain, a brainstem shearing, or any injury to the brain stem, those activities might cease. If we have a brainstem injury we may not be able to breathe on our own or swallow on our own or digest on our own. So that's really important to pay attention to. It's a part of our brain we don't have to think about but it's a really important part of our regulation.

This is also called the primitive brain, it's called the reptilian brain because every reptile has this part of their brain but only this part of their brain and that's why they do very impulsive things. A reptile can only think about survival, they think about I need to sun on this rock, so get some energy and then I'm going feed and eat some bugs and then I'm going to go to sleep and hibernate and I'm going do it again and again. No emotion, they're not worried about what that rock looks like or how they look or who their friends are, it's just survival every day.

This is the part of our brain that's online at birth as well. That's why babies can eat, they can go to the bathroom, they can cry, and they can sleep. Infants when they're first born don't have the larger developmental parts of their brain yet, so it's the brain stem and the cerebellum. In addition, this is the part of the brain that regulates our body's vital functions. This is the part of the brain also we have to think about when we're thinking about body temperature. When we sweat or when we shake because we're cold, that happens with our brain stem and cerebellum. Our heart rate, our rate of breathing, and our balance are also controlled here.

One of the things of the three-part brain to note is that we have to start from the base of the brain and build up for us to have full capacity and full use of our brain. Our brain stem has to be regulated before we can pull into our limbic system and then into our cortex. This is why we feed kids before we give them tests because we know that if we regulate their reptilian brain by feeding them and making sure they get rest the night before, they'll be able to pull into their higher-level thinking skills. This is also why breathing exercises and yoga physical movement work to help regulate the brain and the body because we're accessing heart rate, we're accessing breathing, and we may be accessing balance. That's the reptilian brain, the brainstem.

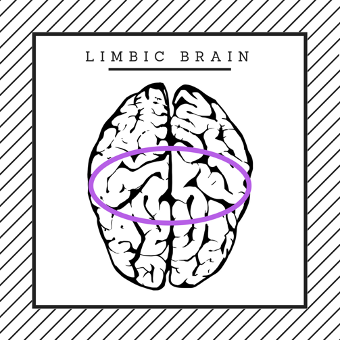

Mammalian Brain

Figure 2 is an image of the mammalian brain:

[Figure 2]

This next part of the brain is called the mammalian brain or the limbic system, it's the middle part of the brain. If you were to take an arrow and draw between your ear and your eye, where they would connect in your head, this is where your mammalian brain is. It’s kind of just midline from the eyes to ears. This is the part of the brain that makes decisions and some judgments. This is also our emotional brain, the emotional center of our brain. This is where we take in and perceive emotions. And the magical organs here as you've probably heard are the amygdala, the hippocampus, and the hypothalamus. The amygdala and the hippocampus are where the magic happens.

The amygdala is the fear center of the brain and the hippocampus is the learning or memory center of the brain. Now they have a converse relationship. The hippocampus kind of sits in the brain like a little half-circle, kind of behind the ears and eyes, and at the ends of the hippocampus, on either end is a cluster of neurons called the amygdala. When the amygdala is set off; when we experience some level of fear in our environment, real or perceived; our brains take in either a real or perceived danger. So, when we experience that our amygdala starts to fire saying, "Oh wait a minute, we're not safe, we have to do something to keep ourselves safe." When the amygdala is triggered, the hippocampus, the learning center, and the memory center of the brain goes offline. That's important to know because what that means is when we experience fear in the body our ability to remember details or to take in information is compromised.

We know this because when a kid is sitting in a classroom and they're worried about, “Is mom going to be safe when I leave home?” Or “Where are we going to sleep tonight?” Or “Am I going to have dinner tonight?” Their ability to focus in school and to really learn is compromised.

I want to be very clear that this does not mean that these kids are not smart. It literally means their brain is in a different state and it's not allowing them to record those memories because it's got to do something to survive. And what happens is when the amygdala is triggered the hypothalamus releases chemicals into the body and those two main chemicals when we feel a state of fear, are adrenaline and cortisol. Adrenaline physically moves our body so that we can do the thing we need to do and cortisol actually acts as a pain reliever.

Evolutionarily we know that if we have to take action to keep ourselves alive we're probably going to get hurt and if we get hurt we're probably going to stop doing that thing that we need to do to stay alive. So, our brains and our bodies do this perfect harmony dance where they say, "Okay, something happened. You need to get safe, you need to run away, you need to fight this, or you need to freeze in the moment and we're going to help you do that. Here's some adrenaline to move the body and here's some cortisol so we don't feel pain so we can stay in this survival mode."

Now what happens is once we get safe and we're no longer threatened by that trauma in our environment or that danger in our environment our body can dissipate those chemicals. So, the adrenaline and the cortisol can be dissolved into our blood system. If we experience trauma over and over again like a chronic trauma or a complex trauma, every day we have to experience that trauma and there's no escape, we can't run away from it, we can't fight it, and freeze might work for a period of time but we're still experiencing that trauma; cortisol stays in the blood in the body a little bit longer.

What we know (we'll go into ACEs a little bit later) is that cortisol in the body over a long period of time causes inflammation in the body and inflammation is the base of almost every disease that we know whether it's cancer or hypertension or diabetes or heart disease. This is why when we talk about trauma impacting the lifespan this is so important, it's the level of cortisol in the body from that stress response that is beautiful in a short moment of survival but long term over and over again is detrimental to our bodies.

This part of the brain is our connection to others, this is where we relate. We regulate in the brain stem and we relate in the mammalian brain or the limbic brain. Our value judgments and emotional regulation are here. Being able to take in input and modulate our emotions, our recorded memories and learning, and then unconscious influences on behavior.

An example of this amygdala, hippocampus relationship that you've probably experienced is, have you ever driven from work to home or home to work and you got there safely but you didn't remember anything about the drive? All right, when I say this in a conference is a bunch of hands go up. That is the weirdest experience, isn't it? When you know you just drove but you don't remember anything about the drive. What happened was in your brain something was worrying you, whether it was you were worried about a client that you had just seen on your way home and you were thinking about them or you were on your way to work and you had your to-do list in your mind, your amygdala was triggered and your hippocampus went offline. Now because you've navigated going home and work and work to home several times, that was on autopilot for you, isn't that beautiful? But that's how our brains and our bodies work together to protect us.

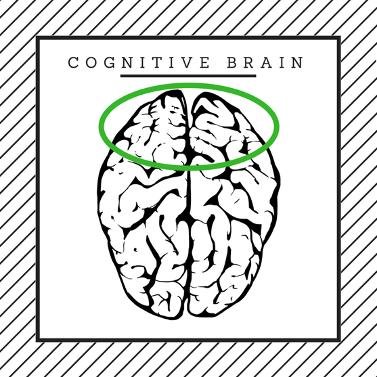

Rational Brain

Figure 3 is an image of the rational brain:

[Figure 3]

The last part of the brain is the rational brain. When you think of a brain, this is the top of it and the outside coating. This is where cognition and learning happens. There's reasoning, this is the neocortex or the thinking brain. This is where we get an accurate representation of ourselves and the world. But again, we have to get all the way up to this part of the brain which means we have to be regulated and we have to feel a sense of connection in some way before we can come into this rational brain.

What that means is when I'm in schools and I'm working with my teachers I remind them we have to make sure that these kids are regulated, that they've slept enough, that they've had enough to eat, that they're hydrated. Then we need to make sure that they feel connected to school, that they know that you want them in your classroom.

When you say hi to them every morning. You know these teachers that have the handshakes for every kid, that's great. You don't have to have something like that but just to look at each kid as they come into the classroom with a smile so they know they're wanted there, that's that connecting to the limbic system. Then those kids can pull into their neocortex and learn and share information and do well on a test.

We have to build that brain up first. This is the rational part of our brain, so it’s regulate, relate, and being rational. This is what makes us who we are. Our self-efficacy and our self-image. This is where abstract and rational thought comes in, foresight, hindsight, and insight come in, imagination, judgment, and logic as well as a developmental in our understanding of language.

I can speak to you and you hear exactly what I'm saying and you're making sense of what I'm saying and you could repeat back to me what I'm saying, you've learned or understood what I said. This is the part of the brain that doesn't fully develop until age 25. I've even seen some studies that are saying now at 27.

This is really important because a lot of policy is made based on this brain science. If you are in the justice system or corrections, you know that recently there's been this information to say that if someone has committed a crime, a non-violent crime before the age of 25, they may not have known fully what they were doing or the consequences of that action so many of those cases are being put down to lower courts or from prisons to local jails so that those folks can be rehabilitated and reintroduced into the community. That social policy and corrections is being influenced by the brain science on this.

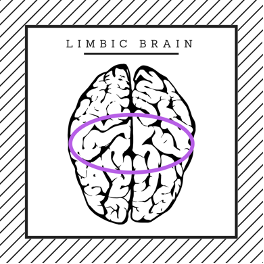

Limbic System: Emotional Center

Figure 4 is an image of the limbic brain:

[Figure 4]

So again, we have our reptilian brain that regulates, our mammalian brain that relates, and our rational brain that helps us be rational and we need all three of those. That limbic system as I mentioned was that emotional center in the mid part of the brain. One of the important parts, I know many of us are familiar with fight, flight, or freeze and those are immediate responses, right? If we can fight a stress or a danger away we'll fight, it if we can't fight it then we might try to run away from it. If we can't fight or run away from it, the most common response is to freeze and allow what's happening to happen and knowing that we'll deal with it later.

When I say freezing and letting what's happening happen that does not mean in any way that we're giving consent to what's happening. I want to be very clear on that. It just means our body and our brain are acknowledging, "We have nowhere to go here, we can't fight and we can't run away so just hunker down." This is also when folks tend to dissociate. Come out of their body because what they're experiencing in that freeze response is too upsetting or too hurtful. They may dissociate and come outside of their bodies. Freeze is the most common response, it's also the response that elicits the most kind of trauma afterwards because we start to ask ourselves, "Why didn't I run? "Why didn't I fight? "Why didn't I scream? "Why didn't I kick back?" And other people then start to ask us those same silly questions, "Why didn't you do this? "Why didn't you do that?" When our body chooses a survival response it is always the right response. Let me say that again, when our body chooses a survival response it is always the right response. Even if it was a freeze. I think that's really important for us to remember.

Another fear Response is fawn. This one is actually what we find a lot with caregivers and social workers and those of us who serve others, is that we tend to in a crisis seek to take care of other people, that's what fawning means. We take care of everybody else's needs, maybe to the detriment of our own. This is why we are social workers but it's something that we really have to take into account and we have to be very aware of and honest with ourselves.

Sometimes that fawn response is wonderful when we can take action and help someone else in a situation, that actually can lessen our own trauma. And I'm finding that during this pandemic, the fact that I can actually continue to work and find my kids and connect with them is making this feel like less of a big trauma for me. And we also have to remember when fawning it may not be in our own best interest. We'll talk about that in part two when we're talking about self-care.

It's really important to recognize that the amygdala is also responsible for some impulse and some aggression control. You can tell that if that is not regulated we might have a child or an older person experiencing aggression or lack of impulse control. The hippocampus is the memory storage and the recall, that spatial memory, and navigation as well as proprioception which is knowing where we are in space, where our body ends and the next one begins.

So again, when we can drive from home to work or work to home and not remember the drive but get there safely that's because our navigation, our spatial memory, and our proprioception are working behind the scenes even while our amygdala is triggered. Now there is research that shows that you can strengthen our hippocampus so that when our amygdala gets triggered our hippocampus stays online and kind of reminds us, "Wait a minute, we've been here before, "we've experienced this before, "we know how to get out of this trauma, we're good." And then the body can calm down, the brain can be regulated and we can take action.

The hypothalamus as I mentioned, releases pituitary hormones, which are responsible for growth, our blood pressure, the sex organs, metabolism, and reproduction. This might be why we may notice that someone who has experienced a lot of trauma especially during developmental stages might actually have growth issues, where they haven't grown because of the trauma they've experienced.

In fact, I had one foster child in my own home who once he came to live with me, I think he was 16. No, he was almost 17 and a half actually 'cause it was toward his aging out. He grew like five inches after he had lived with us for a few months. Once he began to feel safe and regulated in our home and he was so thrilled 'cause he wanted to be really tall. He actually grew five inches and everyone had said he was done growing, he was just going be a little shorty but his body was able to re-regulate to safety and his pituitary hormones kicked in and he was able to grow a little bit, so he was thrilled about that.

Recognizing that this part of the brain also modulates sleep and circadian rhythms, fatigue and pain relief, and input or important aspects of our parenting and attachment behaviors. This is why when we're stressed out we have trouble sleeping, we might not be able to find pain relief. I know for me my sciatic nerve just bangs on me when I'm experiencing stress. So, paying attention to that and how the brain and the body work together to help us understand our trauma and our stress.

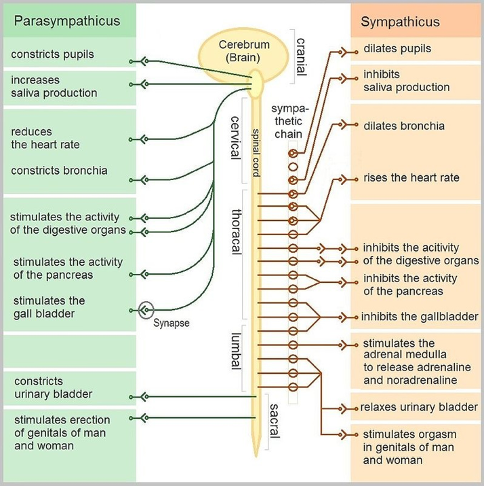

Trauma and the Nervous System

Figure 5 is a graph depicting the impact of trauma on the nervous system:

[Figure 5]

Figure 5 is an interesting graph on trauma and the nervous system. What happens when we are experiencing a traumatic event, our sympathetic nervous system, the one in orange comes online. Our pupils dilate so we can take in more information. We might actually lose our peripheral vision but our pupils dilate so we can take in more. We might notice that we get a dry mouth right away, our heart rate rises. Our heartbeat becomes a little stronger. But what happens is our other organs kind of shut down.

When our body is experiencing stress it knows it has to kind of meeting that challenge. And we don't need digestion to meet that challenge, we don't need reproduction to meet that challenge. So those systems kind of go into a freeze state. This is why folks who experience trauma may experience stomachaches or fertility issues even. Those parts of the body get shut down or frozen. And that's when we might have a young person, I know I've worked with a lot of kids in foster care who've had their guts get really locked up because their brain and body is always in survival mode.

This is really important for us to remember when we have a child with somatic complaints of stomach aches. It all ties back. What happens is we want to shift the body from that state of fight-or-flight in our sympathetic nervous system to a state of what we call to rest and digest and that's in the parasympathetic nervous system.

So when we can engage in some kind of work, whether that is talk therapy, CBT, DBT work or we can physically move our bodies. Taking a walk, getting out in nature, maybe doing some yoga or some breath work, some meditation, some mindfulness we can actually shift our nervous system to the parasympathetic side. And again it's called rest and digest because then our digestion system can come online, our circadian rhythms tend to equal out so we can actually get to sleep. We feel a sense of calmness in the body. The body starts to work, the heart rate gets regulated and all of these other things are happening in the body. The pancreas works, the kidneys work, the liver's working, everything is working well and in coordination when we're in the parasympathetic nervous system.

Take a little bit of time to look at this graph or maybe even google a little bit more about this, it's really fascinating and I think it gives us as social workers really good information when we're working with our clients and those we serve.

Behaviors you might observe

This is a list of some behaviors you may observe when someone has experienced trauma:

- Absenteeism (work/school)

- Increased somatic complaints

- Changes in school performance

- Changes in behavior:

- Increase/Decrease in activity level

- Withdrawal from others or favorite activities

- Angry outbursts and/or aggression

- Decreased attention and/or concentration

- Difficulty with authority, redirection, or criticism

- Distrust of others with both adults and peers

- Inability to interpret and respond appropriately to social cues

- Anxiety, fear, and worry about the safety of self and others

- Increased distress (unusually whiny, irritable, moody)

- Over (or under) reacting to bells, doors slamming, sirens, physical contact, lighting, sudden movements, changes in plans.

If you can notice changes in behavior, changes in performance, changes in effect, missing work, missing school, distrusting folks, noticing a sense of fear and anxiety about the world, about leaving home, about being with other people. And I think just having that oversensitive system where something goes off, we kind of have a startled response.

Again this is the work that we do, right? We get called in when these things happen. As a social worker I get called in schools if a student is missing a lot of school, or behaviors or grades have changed. That's usually a key, hey you know, a little awareness that something might be going on for that child. What's important though to remember and this is something that I have noticed in my work in the last 10 years. If we're only looking for these signs to see if a child needs our support we are going to miss some of the kids who can regulate a little bit more and kind of cover-up these trauma effects.

And what I mean is this, I had a young man who was a straight-A student, perfect attendance, never on anyone's radar until one day he blew up at his math teacher, cursed her out up and down and at the end of it he said, "You have no idea what I'm dealing with." There was an aide in that classroom who had been to one of my presentations about trauma and that aide said, "You need to go talk to miss Nicole." When that student came into my office, we talked a little bit about the outburst and then I asked him, "Well, what is it that "your teachers and I, you know that your teachers "have no idea what you're dealing with?" And that's when this child proceeded to tell me that he and his family were living in an RV. They had been homeless for almost a year and had been living in an RV without any electricity or running water.

You would have never known that if we were only looking at negative behaviors or dissociation or changes in behaviors. Now to be fair it was a change in behavior that brought him to my attention. But until he had that outburst in his class, he wasn't on anybody's radar. It's important for us to remember that sometimes when kids experience trauma they can overachieve to cover it up. They become the straight-A student, the perfect attendance, the kid that does everything and says everything right because they're hoping that if they do that maybe someone will pay attention to them, maybe that's when they'll be worthy of their love instead of the pain and the trauma that they're experiencing. So that's a very important thing to remember as social workers.

Optimum Brain Development & Brain Engagement

Figure 6 is an image of a healthy brain:

[Figure 6]

What we know is for optimum brain development we need all three of those parts of the brain working together. We need to be regulated, we need to feel connected, and we need to have some level of cognitive challenge.

Risk Factors

It's important that we recognize risk factors. Again this is a lot of our work as social workers. Risk factors are defined as any event, condition or experience that increases the probability that a problem will be formed, maintained, or exacerbated. This is our work, finding those risk factors; what is it that's causing this issue? What is this that's causing the problem, right? What is the event, the condition, or the experience that our client has had that has maintained this challenge or formed this challenge or exacerbated this challenge, right?

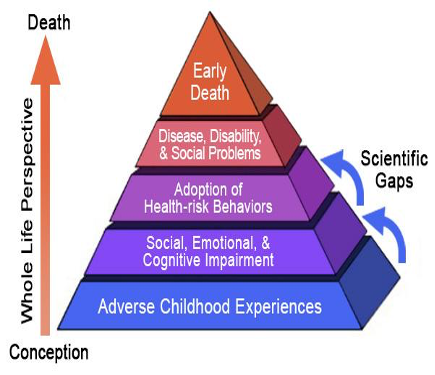

Adverse Childhood Experiences

This is where we get to adverse childhood experiences. ACEs are a risk factor. This has been done as a really comprehensive study. The reference to this report and the study is in the reference pages at the end of this presentation. This is a really important study for those of us in this work to really digest and understand.

It was a study done between 1995 and 1997 and it was about 17,000 patients which is a really good number when we're talking about research. What they found is when they basically gave 17,000 patients a checklist of 10 items and all they had to put was a yes or a no on each of those items and then they got a score from a one to a 10 or zero to 10 based on how many yeses they had. Those 10 items were; emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect. Anyone experiencing mental illness in the household, parental separation, or divorce.

This one's important, I think it's really important that we remember that divorce is a trauma for children. They have no idea what's going on, they just know that their world is being torn apart. While parents might feel like their divorce was really amicable or they talked about it and they knew exactly what they were going to do and split things evenly, for children that is still a really big trauma.

I will say in schools most of the challenges that I deal with are kids who are experiencing pain from their parents' divorce. If you've ever had anyone in the household that had a criminal background or had been arrested or incarcerated, if the mother or stepmother or mother figure had been treated violently, domestic violence or if there was any substance abuse in the household mostly by a caregiver and older sibling.

These were the basic 10 factors for ACEs that they decided to study the first time:

- Emotional abuse

- Physical abuse

- Sexual abuse

- Emotional neglect

- Physical neglect

- Mental illness in the household

- Parental separation or divorce

- Criminal household member

- Mother treated violently

- Household substance abuse

What they found were two-thirds of those folks that they had studied reported at least one ACE. What they were also able to do is tie the number of ACEs, so the dosage of adverse childhood experiences directly correlating those to adverse outcomes in health later in life. So, if you had this many ACEs you're this much more likely to have heart disease or to experience Alzheimer's or dementia as an older person. So, this dose-response relationship is what the ACEs study really brought out and this is vital for our work as social workers.

I have included a link here to the TED Talk from Dr. Nadine Burke Harris. She is the first Surgeon General of California, I'm so excited and proud of her. This TED Talk, she did in 2014 really explains ACEs beautifully and explains the impact on those we serve. I really would encourage you to take time, I think it's less than 20 minutes to really watch that TED Talk. Dr. Nadine Burke Harris also has a book called "The Deepest Well" where she talks about childhood adversity and how we heal it, it's really important. She talks a little bit about how this is a great and dose-response relationship. We know if the dosage of trauma in childhood has impacts on later life health outcomes.

This is a graph (Figure 7) showing the outcomes for ACEs. This is something I really encourage you as social workers to dig into a nerd out on, this is really important for our work. It helps us understand those we serve, it helps us understand kind of our role and what is within our control and what isn't and it also helps us understand ourselves.

Protective Factors

Risk factors are what we are looking at all the time as social workers and that's usually what's being flagged for us. When the risk factor shows up everyone else can say what we need to talk to the social worker. It's protective factors though that we want to get to as social workers and this is where the magic happens. If we can give children those protective factors, preventively. Maybe we can prevent some of the trauma they're experiencing. But it can also be done post-trauma. So that's the other beautiful thing about this is trauma is never the final word.

We can always heal trauma. It may take some time and it might take a little bit more time to undo depending on how complex or ongoing that trauma was for you but trauma healing is possible and that's the beauty of our work. With protective factors what we're looking for is the overall resiliency and that would include these things:

- Courage

- Social skills

- A positive outlook

- Internal locus of control

- Motivation to overcome hardship

- Higher internal valuation of one’s worth (self-esteem and self-efficacy)

A positive outlook, internal locus of control, recognizing what they can control and the power that they have internally. I would also say really having agency which is kind of that an internal valuation of oneself but having agency, knowing that you can make choices for yourself is really important as part of that resilience.

These are skills that we can teach kids and in public education, we talk about social-emotional learning, we talk about building kids resilience toolbox and that's really beautiful, that really can help buffer some of this trauma. And that's really the only way for us to do this work is to prevent or to buffer the trauma and if we can't do those things then it's our job on the back end to try to help heal some of that trauma.

There are individual protective factors and there are community protective factors. Community factors include:

- Equitable access to education

- Childcare and family economic supports

- Positive parenting and parenting support

Having equitable access to education is a protective factor for young people, having child care and economic supports seriously and obviously. I'm not sure why health care and child care are not universal, they should be but that's really important as well. And then positive parenting and parenting support. It can be really easy to demonize parents and to be frustrated with parents if they are traumatizing their children but it's important for us to remember, again, that this is a generational cycle. So that parent might have also had a really disorganized or dysregulated attachment in childhood themselves, they may have experienced trauma and developmental stages themselves so they don't know how to parent a child. That's where we come in again as social workers to offer positive parenting and parenting support. Recognizing that these parents have the capacity to do and love their children and to provide that safe and caring attachment if we can give them the skills and that is really challenging work but it's such valuable work when we are giving parents those skills.

Domains of Protective Factors

There are four domains of protective factors:

- parental resilience

- social connections

- concrete support in times of need, and

- social and emotional competence in children.

Parental resilience is one, social connections are another one. Again, being connected, that part of the brain needs connection. Concrete support in times of need. I am the homeless advocate in my school district. So, when a family needs food I'm giving them food, when they need housing I'm trying to find housing; but maybe we get them into a hotel or we find some other safe place for them to be a shelter or something, concrete support. Not just like, oh, okay, well, we'll get to that or we'll talk about that. Here's what you need.

And then that social and emotional competence of children. These are some things that we as social workers have a direct impact on and isn't that beautiful? That we can be part of that protective factor for those we serve.

And that brings us to the pivot. If we are going to do this work and if we are going to serve those that we serve in a competent way, in a regulated way, in a very centered and present way we must take into account our own trauma, we must understand our own trauma, right?

Understanding Our Trauma

We have to know when we are being triggered when our past traumas are being triggered, and we also have to know if our own dysregulation is driving our behavior in any kind of way. It's a very humbling process and it's always ongoing but we have to understand our own trauma if we want to do this work well.

I love this quote by Naomi Rachael Remen. She says, "the thought we can be immersed in suffering and loss daily and not be touched by it is as unrealistic as expecting to be able to walk through water without getting wet."

We know when we are serving folks who are experiencing trauma we are absorbing that trauma as well. Our nervous system is absorbing that trauma and then our past traumatic issues may be agitated and it's really important for us to be aware of that.

Burnout & Compassion Fatigue

Burnout and compassion fatigue are real. I'm giving just a really quick rundown of what I want to share in part two of this two-part series. So we'll talk a little bit more about these topics in the next series or in the next part. But just to recognize that burnout and compassion fatigue are real in this work. Given what we just talked about all the trauma that we are holding for other folks, you know, and you may see I don't even know how many clients in one day so that is trauma after trauma after trauma after trauma. And we're sitting usually with it, right? Unless we can do walking meetings or we work in a nature preserve or we have the ability to move our bodies while we absorb this trauma but that impacts us, right? There is no way for us to do this work without getting wet.

I appreciate this definition of compassion fatigue. It's a syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment that can occur among individuals who do "people-work" of some kind. And I like that concept of social work as "people-work". But recognizing that there are times when we hit a wall and we might feel that exhaustion, we might even feel a little bit of depersonalization from the work and when we experience reduced personal accomplishment, really feeling like we're not doing enough to help those we serve or feeling like we're not coming to the table with enough tools that can impact us and cause burnout.

Burnout can feel like headaches, a low-grade cold, having a cold for a long time, or having a cough for a long time, and/or feelings of helplessness. I know when it comes to housing in the Bay Area where I work there's a sense of helplessness in trying to find affordable housing for my homeless families.

We can experience fatigue and exhaustion. And what I say is, this is beyond tired. When your bones are tired, when you are tired when you wake up, that's fatigue and exhaustion. We might experience tightness in the chest or in the body, in different parts of the body, or a lack of interest and engagement in our work. Now, this lack of interest and engagement seems really simple but this is detrimental to our work. When we are not engaged with those we serve, when our whole body and bra