Editor's note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Working with Millennials in the “Sandwich Generation”, presented by Jenny Maenpaa, MSW, EdM, LCSW.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Define characteristics of the Sandwich Generation.

- Identify available resources to reduce stress/anxiety often accompanied by challenges plaguing this generation.

- Select helpful interventions to assist "sandwich generation" clients with navigating the balance of caring for oneself, parents, and children.

Introduction

Hi, everyone. Thank you for being here today. Today's topic is Working with Millennials in the Sandwich Generation, Supporting Our Clients In Middle Adulthood. I'm going to tell you a little about who I am so that you understand where I'm coming from and why this topic is important to me. I will tell you who the sandwich generation is, what that means, and what challenges they're facing that might differ from previous generations.

We will cover what we can do as therapists and what they can do after leaving us to feel more supported.

Who Am I?

Who am I, and why should you care that I'm presenting on this today? My name is Jenny Maenpaa, and I am a licensed clinical social worker with a master's in Education of Curriculum and Instruction. I also completed a New York University graduate certificate in Organizational and Executive Coaching. I am the founder of Forward in Heels, an intersectional feminist group therapy practice that empowers all women to stand tall and own their worth so they can light up the world.

For anybody who does not know, intersectionality means that we all have multiple identities. For example, I identify as a woman, a millennial, a highly educated person, and so on. Each of these identities can bring its own power, privilege, and disenfranchisement. In practice, we must name our identities and know how they intersect.

In my 20s, I was the classic overachiever, with multiple graduate degrees, as you heard, and always looking for the next gold star to make me feel valid. I was constantly making lists and plans, only to rewrite them when something unexpected came up, as it always does. I would go to a therapist, and after the first three sessions, they would say, "Well, there's nothing wrong with you." I would think, "Okay, I just have to work harder. Message received." This is the absolute wrong message for an overachieving millennial. Finally, I realized that I suffer from high-functioning anxiety. Even though I can sublimate my anxious tendencies into achievements does not mean it does not negatively impact me. So I created the practice I wish I had had access to in my 20s. One that recognizes that being a badass does not mean you never have doubt and that being the strong one does not mean you never need to be checked on. And being the one everyone always goes to for solutions does not mean you are never vulnerable. What makes me come alive is seeing women realize the unlimited potential within them. When women can take care of themselves, their light shines through, and the best version of themselves can show up professionally. This person stands tall, knows her worth, and lights up the world.

Five employees in my practice combine cognitive behavioral and psychodynamic therapy to help stressed out and overachieving women overcome imposter syndrome and dissatisfaction. As a result of working with my therapists, women go from just chasing the brass ring to achieving sustainable happiness in every aspect of their lives.

Who is the Sandwich Generation?

- Usually, middle adults between 30s and 50s in a family who are responsible for raising their own children, working, and caring for their parents

- Defined as those who have a living parent age 65 or older and are either raising a child under age 18 or supporting a grown child

- Female middle adults are most likely to be responsible for taking care of their parents. If there are no daughters in the family, then the duties often fall to the elder son.

We must start with a definition and the characteristics and then identify available resources to reduce stress and anxiety often accompanied by the specific challenges plaguing this generation. We can then establish helpful interventions and apply learning tools to help them navigate the balance of caring for themselves, their parents, and their children for the sandwich generation.

I also want to issue a disclaimer. We will be speaking in broad generalizations today; not everything will apply to every client. We will also use gendered language because that is how most of the research has been conducted. Please treat today's information like a buffet. Take what you want, and leave the rest.

Two social workers, Dorothy Miller and Elaine Brody coined the term sandwich generation back in 1981 to describe caregivers sandwiched between generations. Statistics show that 47% of adults in their 40s and 50s support an aging parent 70 or older while managing their children.

The typical American sandwich generation caregiver is female, in her mid-40s, married, and employed. Unfortunately, stereotypical parenting and gender roles have conditioned many American households to place the responsibility of caregiving on working mothers in their 40s. Consequently, 70% of women and only 30% of men have adopted the responsibility to care for an elderly relative with chronic health issues, which causes an imbalance in expectations and increases familial stress. The sandwich generation assumes responsibilities and services like transportation, meal planning, healthcare, and general housekeeping for their children and parents. On average, adults in the sandwich generation spend $10,000 and 1,350 hours of work on their parents and children annually. While caring for an aging parent, essential familial stress becomes difficult to ignore and predictably influences your caregiving style.

As a review, the sandwich generation comprises middle adults between their 30s and 50s in a family responsible for raising their children, working, and caring for their parents. Of course, this can also include a spouse's parents or stepchildren. These are broad generalizations but what we think of generationally. It consists of those with a living parent 65 or older and raising a child under 18 or supporting a grown child. We saw this in the pandemic and the great recession (2008 and the following years), which led to many post-high school and post-college children living with their parents because of financial disparities. This is called "boomeranging" when children go back to living at home.

Again, these are middle-aged females responsible for taking care of their parents. If there are no daughters in the family, then the duties often fall to the elder son. There is not enough research on people who identify as gender binary.

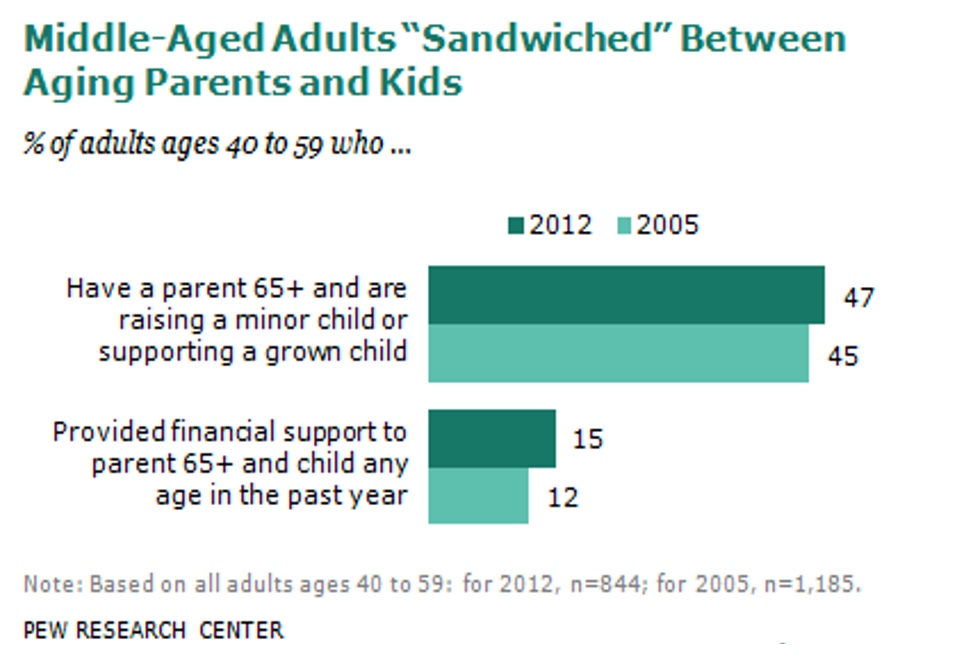

Why are so many people in the sandwich generation, and why is it a big issue? It is a perfect storm of several factors. For starters, everyone is living longer, and often there are insufficient funds to manage retirement and healthcare needs. Figure 1 shows statistics from the Pew Research Center.

Figure 1. Pew study about % of adults sandwiched between aging parents and kids.

A Pew study from 2015 found that 28% of Americans provided financial help to a parent 65 or older due to increased length of retirement and the cost of healthcare. Fidelity Investments projected that a 65-year-old couple retiring in 2021 would spend an average of 300,000 on healthcare over the rest of their lives, and that is with Medicare. Meanwhile, the age at which we have children has steadily increased over the past couple of decades, meaning people are more likely to raise children into their late 40s and early 50s. And a tough job market coupled with significant student loan debt has kept millennials living at home longer. Almost six out of 10 adults gave their children from ages 18 to 29 financial support during the year preceding the Pew surveys in June 2019. When I say millennial, it still sounds very young in terms of the media. Here is a headline, "Millennials can't buy houses because they're eating too much avocado toast." Or, "Millennials are killing the wedding industry (or housing industry)." You hear it over and over again. Most estimates put millennials as being born between 1980 and 1997-ish. Millennials are not 25-year-olds having brunch every week and unable to afford a house. The term millennial is primarily focused on people in their 30s that are in prime childbearing ages and buying homes.

According to data from an AARP Public Policy Institute Study, working and non-working caregivers are likely to experience stress associated with sandwich caregiving. Non-working caregivers may feel they have no time away from their responsibilities of caring for their children and elderly parent, while working caregivers may feel forced to sacrifice things in their careers to manage their caregiving duties. Seventy percent of working caregivers have had to change jobs to accommodate caregiving. These job changes range from reducing work hours to adjusting roles or leaving work entirely for some time. These changes leave some to feel like they are only a "caregiver" where once they were a banker, an administrative professional, a plumber, or an electrician. This transition can be frustrating and challenging.

As we know from Erik Erikson's 8 Stages of Psychosocial Development, stage seven is the adulthood period of generativity versus stagnation. This stage can be appropriately processed through virtuous care as maldevelopment is rejectivity. An example of a positive engagement with the next generation is through parenting, coaching, or teaching. This stage usually occurs during middle adulthood, which Erikson's data says is more like 40 to 65 years old. These numbers keep shifting, and there are no hard and fast rules. Generativity refers to making your mark on the world by creating or nurturing things that will outlast an individual. Individuals want to make positive changes that will benefit other people. When I think of this, I hear the Hamilton song where he sings, "I want to create something that's going outlive me." We give back to society through raising our children, being productive at work, and becoming involved in community activities and organizations. We develop a sense of being part of the bigger picture through generativity. Success leads to feelings of usefulness and accomplishment, while failure results in shallow involvement in the world. By failing to find a way to contribute, we can become stagnant and feel unproductive. These individuals may feel disconnected or uninvolved with their community and with society as a whole. Again, success in this stage will lead to that virtue of care.

Psychologically there is a cognitive dissonance between the intention of creating things that will outlive the individual and the implementation of focusing that care primarily on caring for an elder. By definition, the person is unlikely to outlive the client, and this can cause identity crises and lead to stagnation. Even if our clients feel they are constantly doing and creating, their actions may not be in service of a legacy.

On the other side, the elderly family member being taken care of may struggle in stage eight, ego integrity versus despair. Ego integrity versus despair is the eighth and final stage of Erik Erikson's stage theory of psychosocial development. This stage begins at approximately age 65 and ends at death. During this time, we contemplate our accomplishments and can develop integrity if we see ourselves as having led a successful life. Individuals who reflect on their lives and regret not achieving their goals will experience bitterness and despair. As we grow older and become senior citizens, we tend to slow down our productivity and explore life as retirees. Erikson believed that if we see our lives as unproductive, feel guilt about our past, or feel that we did not accomplish our goals, we become dissatisfied with life and develop despair, often leading to depression and hopelessness. Success in this stage will lead to the virtue of wisdom. Wisdom enables a person to look back on their life with a sense of closure and completeness and accept death without fear. A continuous state of ego integrity does not characterize wise people, but instead, they experience both ego integrity and despair. Thus, later life is characterized by integrity and despair as alternating or complimentary states that must be balanced. Your client may provide care for an elderly family member who feels that they did not meet their ego integrity by being productive or accomplished enough. In this case, they may be angry, resentful, or bitter. Your client may feel guilty over being angry or frustrated with this family member. Often they think that after all this parent has given them, they have no right to be resentful of this caregiving role, and yet they are. Your client may feel they are not allowed to feel any negative emotions and shove these feelings down. This can lead to those emotions coming out elsewhere, whether with their nuclear families, at work, with their friends, or often on themselves.

With an aging population and a generation of young adults struggling to achieve financial independence, the burdens and responsibilities of middle-aged Americans are increasing. Nearly half, 47% of adults in their 40s and 50s have a parent aged 65 or older and either raise a young child or financially support a grown child aged 18 or older.

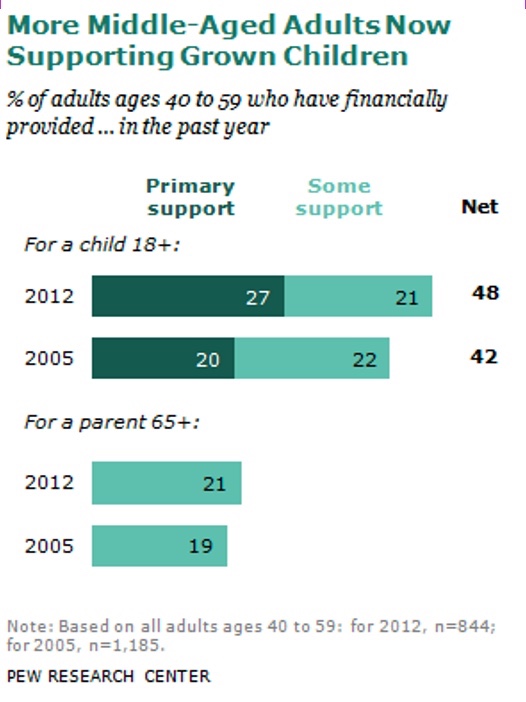

About one in seven middle-aged adults, about 15%, is providing financial support to an aging parent and a child. While the share of middle-aged adults living in the so-called sandwich generation has increased marginally in recent years, the financial burdens associated with caring for multiple generations of family members are mounting. The increased pressure comes primarily from grown children rather than aging parents. According to a new nationwide Pew Research Center study (Figure 2), 48% of adults ages 40 to 59 have provided financial support to at least one grown child in the past year, with 27% providing the primary support.

Figure 2. Pew study about how more middle-aged adults now support grown children.

These shares are up significantly from 2005. By contrast, about one in five middle-aged adults, 21%, have provided financial support to a parent age 65 or older in the past year, which is basically unchanged from 2005.

Looking at only adults in their 40s and 50s with at least one child age 18 or older, 73% have provided at least some financial help to at least one such child in the past year. Many support children still in school, but a significant share says they are doing so for other reasons. In contrast, among adults that age who have a parent 65 or older, only 32% provided financial help to a parent in the past year. While middle-aged adults are devoting more resources to their grown children these days, the survey finds that the public places more value on support for aging parents than on support for grown children.

Again, there are disparaging reports about younger generations being lazy or entitled and younger workers feeling entitled to employment support, whether paid time off, raises, or promotions. This leads to talk about a generational divide. And so, it makes sense that people feel judged, at least based on this study about grown adults who choose to support their grown children more so than their elderly parents. Among all adults, 75% say adults are responsible for providing financial assistance to an elderly parent in need. In comparison, only 52% say parents have a similar responsibility to support a grown child. As I mentioned before, Pew research states the likely explanation for the increase in the prevalence of parents providing financial assistance to grown children is that the Great Recession (2008) and sluggish recovery took a disproportionate toll on young adults.

Presumably, life in the sandwich generation could be a bit stressful with all my described characteristics. Having an aging parent while still raising or supporting one's children presents challenges not faced by other adults, like caregiving and financial and emotional support. However, interestingly, the survey suggests that adults in the sandwich generation are just as happy with their lives as other adults. Thirty-one percent say they are very happy with their lives, and an additional 52% say they are pretty satisfied. Happiness rates are nearly the same among adults not part of the sandwich generation, with 28% as compared to 31 being very happy, and 51% pretty happy as compared to 52%. These figures are interesting because we are conditioned to look for the problem and see where we can intervene. We are much less conditioned to look for where things might be going well within a more significant challenging situation. Some people are happy that they get to be part of multiple generations. This is not to say we should not address and identify challenges, but it is essential to have both perspectives. A hallmark of our profession is holding these multiple thoughts together at once. However, sandwich generation adults are somewhat more likely than other adults to say they are pressed for time. Among those with a parent age 65 or older and a dependent child, 31% say they always feel rushed to do things, while only 23% of other adults report the same.

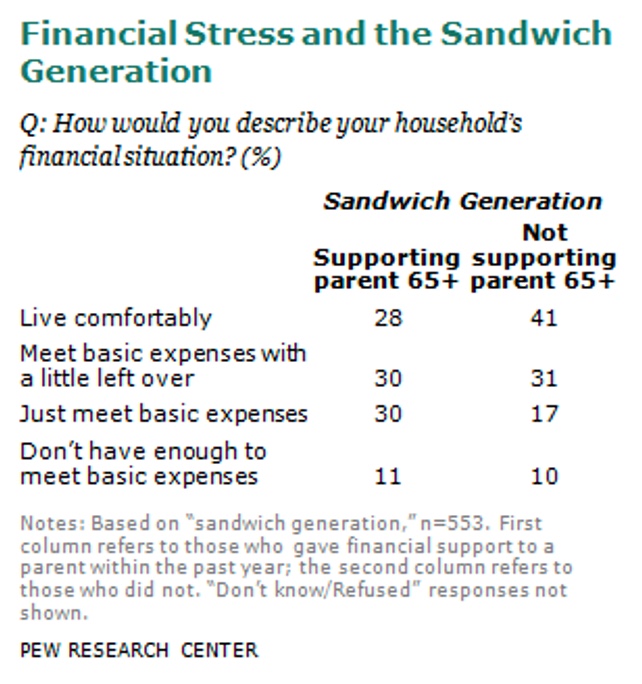

For members of the sandwich generation who have an aging parent but have also provided financial assistance to a child, the strain of supporting multiple family members can impact economic well-being (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Pew study about financial stress with the sandwich generation.

Survey respondents were also asked to describe their household's financial system. Among those providing financial support to an aging parent and supporting a child of any age, 28% said they live comfortably, 30% said they have enough to meet their basic expenses with a little leftover, 30% said they are just able to meet their basic expenses, and 11% said they did not have enough to meet their basic expenses. By contrast, 41% of adults sandwiched between children and aging parents but not providing financial support to an aging parent say they live comfortably.

When survey respondents were asked if adult children are responsible for providing financial assistance to an elderly parent in need, 75% said they do, with only 23% reporting that it was not an adult child's responsibility. By contrast, only half of all respondents, 52%, said parents should provide financial assistance to a grown child if they need it. Some 44% said parents do not have a responsibility to do this.

I know I am throwing a lot of numbers at you, but I think it is essential to identify what is happening with people in this situation. We also want to look at all the mixed, conflicting, and confusing messages that our clients are receiving. Even the definition of a millennial can be confusing. Are they aged 30 to 40 or middle adults aged 40 to 65? And, there can be people in any of those decades that can be in this position. You might have a client who had their first child in their late 20s and by their late 30s are managing an adolescent and an older adult. You might also have a client who had their first child in their 40s and doing the same thing.

It is not about the particular generational like years, and it is more about the life circumstances. These charts and data are dry and boring, but it is essential to understand what the trends are. I sometimes generalize using a very small sample set, and I start to think everybody sees things that way. Then, I will encounter someone who says, "No, I see it completely differently." Remember, datasets can be skewed. I like to stop and look at the data and see if it is what I thought.

Back to the question of whether parents have a responsibility to support their grown children, personal experience seems to matter. Parents whose children are younger than 18 are less likely than those with a child aged 18 or older to say that it is a parent's responsibility to provide financial support to a grown child who needs it. And those parents who are providing direct financial aid to a grown child are among the most likely to say, "This is a parent's responsibility." If we put that in lay people's terms, that makes sense. If you are the parent of a teenager who is not yet 18, and society has told you that when they turn 18 that they are no longer going to be your financial responsibility, you may feel differently. You might look at parents who financially support their adult children 18 and older and say, "They're spoiling them, or their kid's entitled." However, when your child turns 18, you may sing another tune. Clients may have divides in their families and support systems where everyone has different opinions on their actions.

While most adults believe there is a responsibility to provide for an elderly parent in financial need, about one in four adults have done this in the past year. Among those with at least one living parent, aged 65 or older, roughly one-third say they have given their parents financial support. This is more than just a short-term or one-time commitment for most of these. About 72% of those who have provided financial assistance to an aging parent say the money was for ongoing expenses.

Overall, Americans are still more likely to provide financial support to a grown child than an aging parent. Here is where the burden falls much more heavily on middle-aged adults than their younger or older counterparts. Among adults aged 40 to 59 with at least one grown child, 73% say they have provided financial support. Among those 60 and older, only about half say they have. Very few of those under age 40 have a grown child, so the data does not apply in terms of study validity and reliability. While some aging parents need financial support, others may also need help with day-to-day living. Among all adults with at least one parent age 65 or older, 30% say their parents need help to handle their affairs or care for themselves, while 69% say their parents can handle this independently. And middle-aged adults are the most likely to have a parent aged 65 or older, and of that group, 28% say their parent needs some help.

Again, I do not expect you to memorize these numbers. The point is that it is not just financial support but also day-to-day living, emotional support, and facilitating access to resources. For those in their 50s and beyond who still have a living parent, the likelihood that the parent will need caregiving is relatively high. Half of the adults age 60 or older with a living parent say the parent needs help with day-to-day living. For example, age 60 is nearing retirement age, but you may have a 20-year-old adult child who may still need support, whether in college or figuring out their way in the world, and a parent in their 80s or 90s. I keep saying "generation," but you can see how it may skew in decades in each direction.

When aging adults need assistance handling their affairs or caring for themselves, family members primarily help out. Among those with a parent age 65 or older who need this type of assistance, 31% say they provide most of the help, and an additional 48% provide at least some help. In addition to helping their aging parents with day-to-day living, many adults report that their parents rely on them for emotional support. Knowing what we know, especially during the pandemic of some of the conditions within assisted living homes and retirement communities, it is not surprising that people would try to do everything themselves before they turn to a facility or an in-home healthcare worker. As we know, control is one of the antidotes to anxiety for our clients. Caregivers may want to control the situation even if it is not within their abilities.

I gave you a lot of data to frame this talk. Now, we are going to talk about your individual clients.

Observable Signs of a Client Caught in the Sandwich Generation

- Client expresses feeling increased stress and responsibility for others in extended family

- Client expresses not feeling there are enough hours in day/resources available to do everything needed

- Client expresses worry over how to pay for everyone's care

What are the observable signs of a client caught in the sandwich generation? Symptoms may feel like one is carrying lots of stress and the world's weight on their shoulders. Individuals often feel overscheduled and like they have the pressures of two generations, which does not even include their stresses. They are often externally focused on the parent and the child, forgetting that they are part of that multi-generation household. They may experience a decline in health as a result.

There can be feelings of guilt and false guilt, guilt which no origin in actual actions. It makes our clients feel like bad people even though they have not done anything to inflict pain on anyone intentionally. It is quite the opposite, but they feel like they are trying to do it all and failing everybody. It is an impossible situation to please everybody, but it does not mean that it does not feel like a failure.

Caregivers also experience grief. They mourn the relationships they expected with their parents and their kids. There may be grief over not being able to have the home life envisioned for the kids, with dinner on the table every night or calm family times. And there may be grief over losing companionship with a parent as the roles change. Anticipatory grief is grief that occurs before death or loss. It is common among people facing the eventual death of a loved one or their own death. Most people expect to feel grief after a death, but fewer are familiar with grief that shows up before life ends. As this kind of grief is not often discussed, clients might worry that it is not socially acceptable to express the deep pain that they are feeling. They might not get the support they need and deserve from people who say things like, "Well, at least you still have your parents." Clients may be grieving several losses. Their parents are getting older and nearing death, and their family roles might be changing. There can be role reversals, where they are now the head of the family instead of a parent.

They may fear losing their financial security. The idea is that your parents will always be there for you if you need them. Losing their financial support might change how our clients feel about their future. They may also want the relationship with their parent that they either had before and want again or one that they always thought they would have. While anticipatory grief is similar to grief after a death, it is also unique in many ways. Grief before death often involves more anger, loss of emotional control, and atypical grief responses. As these unexpected emotions are in an in-between place, they might feel mixed up as they try to find the balance between holding onto hope and letting go.

Grieving before someone dies is not good or bad. Some people experience little to no grief when a loved one is dying. Some feel grieving in advance and may be seen as giving up hope. For others, the grief before the actual loss is even more severe. Grief before death also is not a substitute for grief later. Unfortunately, there is not a fixed amount of grief, and anticipatory grief will not necessarily shorten our client's grieving process. Even if their loved one's health has been declining for a long time, nothing can prepare someone for the actual death. But while anticipatory grief does not give them a head start on later grieving, it does provide opportunities for closure. During closure, a relationship may be repaired or processed while the parent is still alive.

The sandwich generation faces mental health challenges caused by the emotional, financial, and physical toll of raising children while also caring for parents or elders who may have limited or no independence. These individuals can find it difficult or even impossible to find enough time in the day to meet the demands of children, parents, work, and other life tasks. This may leave little time for what we know contributes to maintaining mental health, such as exercise, healthy eating, rest, sleep, quality time with a partner, and social life. Finances can be a significant source of stress and anxiety for these individuals as they face the cost of providing for children and their parents. Members of the sandwich generation also often face caregiver burnout and depression from feeling stagnant and isolated in their role as a caregiver.

They may have anxiety as they try to balance multiple roles at once, which can range from being a caregiver, a parent, an employee, and especially those who were remote workers during the pandemic. All those lines are blurred, and everybody's in the same space all the time. Any kind of self-care or rest is often on the back burner, as they spend most of their time caring for those around them and feel they cannot allot any time to themselves. And if they do, there is a sense of guilt and shame. The lack of self-care and rest often has significant physical consequences, such as a weaker immune system, strain on the heart, and obesity due to insufficient energy to exercise and prepare and eat healthy meals.

The sandwich generation may also feel alone, isolated, and overwhelmed. These conditions can lead to burnout, and left unchecked can lead to depression, anxiety, substance use, and other mental health conditions. Anybody who is simultaneously caring for children and aging parents might be at risk for these health and happiness hazards. Some individuals may face additional obstacles. For example, caring for a parent can be triggering due to past dysfunction or abuse. This creates a challenging situation where someone is trying to reconcile their upbringing while learning to be a parent to their children. This can resurface some extreme emotions and even trauma.

Individuals often feel financially squeezed because the average cost of childcare is $4,320 a year. The average price of a nursing home is $235 per day. As I mentioned, 70% of working caregivers have had to change jobs to accommodate caregiving, ranging from reducing work hours to changing roles or leaving work altogether. One potential financial risk of being in the sandwich generation is the cost of childcare and elder care outpacing the client's earnings. The caregiver may also miss promotions and corporate opportunities due to taking time off work or not being able to stay late. They may not attend optional things like happy hours or take on extra projects. This can impact their job and earning potential, which turns around and causes more stress in trying to pay for childcare and elder care.

- Higher levels of stress hormones

- More days sick with an infectious disease

- Weaker immune response to influenza, or flu, vaccines

- Slower wound healing

- Higher levels of obesity

- Higher risk for mental decline

Listed are some more health impacts. Many sandwich generation caregivers experience higher levels of stress hormones known as cortisol. Cortisol is a glucocorticoid hormone that your adrenal glands, which are the endocrine glands on top of your kidneys, produce and release. Cortisol affects several aspects of your body and helps regulate your body's response to stress. Hormones are chemicals that coordinate different bodily functions by carrying messages to your organs, skin, muscles, and other tissues. These signals tell your body what to do and when to do it. Glucocorticoids are steroid hormones that suppress inflammation in all of your bodily tissues, control metabolism in your muscles, fat liver, and bones, and affect sleep-wake cycles. Your adrenal glands, also known as your supra renal glands, are small triangle-shaped glands located on top of the kidneys and are part of the endocrine system. Your body continuously monitors your cortisol levels to maintain steady levels, otherwise known as homeostasis. Higher or lower than average cortisol levels can be harmful to your health. It is commonly known as the stress hormone because it impacts your whole body and regulates your body's stress response.

Everything I have described so far falls under that chronic stress umbrella. And almost every tissue in your body has those glucocorticoid receptors. As such, cortisol can affect nearly every organ system in your body, including the nervous, immune, cardiovascular, respiratory, reproductive, musculoskeletal, and integumentary systems. This is why people who are stressed out might say that their hair is falling out or they have an acne breakout. Adrenaline, the fight or flight hormone, adrenaline, triggers the release of glucose and sugar from your liver for fast energy during stress. When we get sick, we often say, "My immune system is run down." Those that are stressed are more prone to infectious diseases like the common cold, flu, or COVID. There may also be a weaker immune response to a vaccine.

There may also be slower wound healing, obesity, and a higher risk for mental decline.

External Strategies to Support the Sandwich Generation

- Seek therapy before the crisis erupts

- Make financial plans that are logical rather than emotional

- Focus on emotional coping skills to implement on their own

- Remind self not to seek perfection but "good enough" solutions

Your clients may already be in therapy. Otherwise, you would not be here talking about this. However, they may not always recognize that this dual role that they are occupying is a stressor worthy of addressing. They differentiate "real problems" from everyday problems. I have to remind them that just because they have the same problem as somebody else does not make it any less impactful or stressful.

First, you can start a conversation about this stressful role and then intervene before a crisis. Perhaps this is not affecting them currently, but your clients can look ahead towards the pressures of being a sandwiched person.

Many people do not want to talk about money. And by the time they do, it is emotional because things have to happen. We must help them understand that prioritizing paying themselves first means planning for their retirement and needs, as scholarships and loans do not exist for retirement as they do for college. If given the choice between paying for their parents, putting away money for their retirement, and paying for their children, I like to remind them that children are the only ones eligible for a loan. Now, do not get me started on the student loan system. I am not saying it is a great system, but in terms of actual options, this may be the only one.

Your clients also need to talk to their parents about money. It is tough to predict how people will respond to this situation, but they can at least start to get some indication of their parent's financial situation. Nobody wants to be scrambling to figure this out when the parent is in the hospital, on hospice, or is gone. There may be enough time to have your clients help their parents change some things about their financial situation. They can take stock of debts or liabilities and figure out their pensions, social security, health insurance, and general spending. It may be as simple as canceling subscriptions.

One thing you can do is model these challenging conversations with our clients through role-playing. "I understand you're reluctant to begin this conversation. Let's like keep practicing until you feel a little more comfortable."

We can also focus on emotional coping skills for them to implement. This can be important for both the clients and their children. It is essential to set expectations for grown children who are being supported. There is a big difference between those getting on their feet temporarily and those who expect to live at home permanently. Clients may need to set boundaries and parameters. Are they contributing to the household, planning to get a job, going to school, or moving out? How can the client support them in their journey instead of just helping them financially? And how long is this going to last?

Emotional coping involves cognitive efforts to regulate the emotions that arise from stressors to relieve emotional distress and consists of strategies like positive reframing, venting, and using humor. Avoidance-focused coping seeks to avoid the stressor through distraction, disengagement, or denial. Are the clients keeping busy to avoid thinking about the things they do not want to or are they able to vent about the challenges and positively reframe all the things bothering them? Ask your client, "Where are you centered in this? Are you considering your emotional well-being? When financially supporting struggling young adults and dependent elders, you also support them emotionally."

According to the Pew study, almost a third of the people in the sandwich generation admitted to feeling rushed. Science tells us that the feeling of not having enough time in the day is a serious detriment to life happiness in times of stress. Women, in particular, are affected by this phenomenon since they are traditionally expected to care for children and aging family members. The most significant cost can be the relationship with the parents. We must remind our clients that holding everything in and being a martyr may harm the relationship they seek to support.

Financially, there may be other options available. And considering the day-to-day costs, including relationship costs, are there resources to hire someone? Many of our clients think good enough is not enough. Being kind to a parent may mean considering an assisted living or nursing care facility where they can be safe and get the help they need. It might not be what everybody wants, but it might be the best caring action for the parent, the client, and the family. Being kind in the other direction can also mean limiting kids' activities to reduce strain on time and resources. Our client's children may need to choose between soccer and football, or maybe the child has to get a job to pay for one of those activities. There are different solutions so that our clients do not have to be the sole nucleus of holding all of this stress and responsibility.

There can also be non-financial delegation. Can kids take on additional chores at home, like doing the laundry or cleaning the kitchen? An older child can do pickups from sports and clubs to give our client time to help the elderly parent with their exercises from physical therapy. Adult siblings of the client can lend a hand with parent care or follow up on medical appointments or information gathering. Often, our clients forget that delegation is an appropriate way to ask for help. As I mentioned earlier, the sandwich generation usually adopts responsibilities for meal planning, transportation, and healthcare, which are huge asks.

- Create systems for meal planning

- Seek out additional resources for transportation supports

- Consult with professional resources for healthcare decisions, like

- Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs)

- Community resources

- Dependent care

Meal planning might sound like a strangely specific example, but many older people often stop prioritizing their activities of daily living like bathing, grooming, and eating regular meals. Enlisting clients' children or siblings in meal prepping, like easily microwaveable and portioned meals, shelf-stable meals, and Meals on Wheels can take the pressure off our clients.

Older relatives are often also reluctant to give up their cars and driving abilities, seeing it as a significant loss of independence and autonomy. Transportation is a major factor that helps older adults continue living independently and links them to the services they need. Whether they drive their cars or utilize a public bus, older adults depend on accessible transportation to get them everywhere, from grocery stores to doctor offices.

The Older Americans Act provides assistance for supportive services and senior care, including transportation assistance and public transportation assistance, enabling seniors to remain in their homes for as long as possible. Another resource is the National Aging and Disability Transportation Center. No matter where your client lives, they should be to Google l "elder transportation near me," and they will likely find resources.

We also forget what our companies can offer. Many companies offer employee assistance programs and dependent care resources within the company's financial structure. Certain funds may be allocated for caregiving via tax breaks and partnerships with external community resources. There are also often legal and financial resources available within large companies that can help clients begin to formulate a plan when overwhelmed.

Finally, if there is a short-term need requiring a lot of concentrated time, like moving a parent into an assisted living facility over the span of a couple of weeks, clients can consider FMLA, the Family and Medical Leave Act, which provides certain employees with up to 12 weeks of unpaid job-protected leave per year. FMLA is a federal program that depends on the size of the company, health insurance status, and length of time you have worked there, but it is something to consider.

What strategy could you use immediately with a client in this generation? Here are some poll answers (from the live course):

- Seeking therapy before the crisis erupts

- Making financial plans that are logical, rather than emotional

- Focusing on emotional coping skills to implement on their own

- Reminding them not to seek perfection, but good enough solutions

- Creating systems for meal planning

- Seeking out additional resources for transportation support

- Consulting with professional resources within their companies for healthcare decisions

The number one response chosen (67%) was, "Reminding your clients not to seek perfection, but good enough solutions." Others chose "Seek therapy before the crisis erupts," "make financial plans that are logical rather than emotional," seek out additional resources for transportation supports," and "consult with resources for healthcare decisions." Many people also responded that their clients have not thought about financial plans in advance.

Managing Caregiver Fatigue

- Acknowledge they can't do it all alone

- Set boundaries

- Let go of what they cannot control

- Positive reframing

- Reclaim time

- Identify stressors

- Recognize existing coping strategies

- Prioritize self-care

- Explore additional supports

These final slides are tips for beginning to manage caregiver fatigue.

Acknowledge They Can't Do It Alone

Number one is acknowledging that they cannot do it independently and need to ask for help. It sounds simple, but many of our clients forget to do that. Let their partners or closest friends know that sometimes they just need them to be present. This could simply be sitting with them so that they are not alone.

If they have younger kids and the grandparents are relatively healthy, grandparents can be a source of childcare, providing much-needed relief for our clients when working either inside or outside the home. This can also give purpose to the grandparents, who often at this age feel like maybe they do not have one. It gives kids an experience of spending time interacting with the older generation. It is an excellent way to foster a sense of responsibility and respect for elders.

Releasing control is another option. If someone asks our clients if they can help with any specific tasks, their default response is often, "No," so they are not a burden. Our clients need help recognizing that allowing someone else to take care of a meal or pick up their children from school for the day can immensely help ease the burdens. They can remind themselves, "I'm missing dinner with my kids to take my parent to a doctor's appointment." This helps them remember that the way things are now is not necessarily how they will always be.

Set Boundaries

We love setting boundaries, but it often sounds like rejection to our clients. Subconsciously, they may feel that if they ask for what they need or want, others will not meet those needs, and they will be alone. Their catastrophizing brains do not allow them to entertain the possibility of others meeting their needs. Boundary setting is not to keep others out but to invite them in. It will enable others to know what our clients need and want and to work within those parameters. Sometimes that looks like setting a timer for a kid and saying, "Until this goes off, you cannot bother me. But once it goes off, I'm all yours." Setting that boundary means not saying, "Don't bother me," but rather, "This is the time I need, and then I'm all yours." Instead of splitting focus, it is a 100% focus on one thing.

Letting Go of What They Cannot Control

Our clients love to try to control things. There will be moments of levity and happiness within the burden. For example, there may be a moment when an elderly parent with dementia remembers something or the client. That moment can stay with our clients. This does not mean that the person does not have dementia or things are not hard. It is about having a positive moment and letting go of things out of your control.

Positive Reframing

Positive reframing is another one we love. It is not pretending everything is fine when it is not or stopping our clients from experiencing painful or negative emotions. It is about saying, "I'm frustrated right now. And I wonder what I can change." Can they change the distribution of work within their family, ask for flexibility at work, or move some money around to hire someone to free up their time? Can they change their expectations about how much can be accomplished on any given day and start to feel a little bit better?

Reclaiming Time

This could be as simple as bringing a sketchbook or book to the parent's doctor's appointment or trading carpool days with another parent or a spouse. It is reclaiming that time.

Identify Stressors

Often, clients carry many stressors related to all the decisions they have to make. A family meeting with an agenda might work where they can provide their family with concrete examples. Then, people can start to propose solutions where everyone can participate. Our clients often stay siloed in thinking and forget to ask for help, or the people in their families do not know how to help them.

Recognize Existing Coping Strategies

There is a reason we repeatedly bring up the same things for coping strategies as they work. These include consistent exercise, healthy stress-reducing activities, short walks, talking with friends, and things our clients already like. They do not have to be these brand-new solutions. Often our clients think that self-care has to be this significant event, like a spa day or phones off for eight hours. It can be simple, like eating a healthy diet, going to bed at the same time, or getting seven to nine hours of quality sleep with no interruptions.

Exploring Additional Supports

They may need to explore additional supports like finding a resource within the community that they have not thought of, like a senior center. Senior centers have things like walking clubs, painting clubs, et cetera.

Summary

I appreciate you being with me today. I know we are all trying to shoulder our responsibilities and those of our clients. I appreciate the work that all of you do.

References

Aazami, S., Shamsuddin, K., & Akmal, S. (2018). Assessment of work-family conflict among women of the Sandwich Generation. Journal of Adult Development, 25(2), 135–140. https://doi-org.proxy.library.nyu.edu/10.1007/s10804-017-9276-7

Duxbury, L., Halinski, M., & Stevenson, M. (2022). Something's gotta give: The relationship between time in eldercare, time in childcare, and employee well-being. Journal of Aging & Health, 1. https://doi-org.ezproxy.uu.edu/10.1177/08982643221092876

Estioko, D. A. C., Haveria, M. M. A., Veloso, E. B. R., & Teng-Calleja, M. (2022). Experiences of intergenerational caregiving among women belonging to the Sandwich Generation: An example from the Philippines. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 1–18.

Evans, K. L., Millsteed, J., Richmond, J. E., Falkmer, M., Falkmer, T., & Girdler, S. J. (2019). The impact of within and between role experiences on role balance outcomes for working Sandwich Generation Women. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 26(3), 184–193. https://doi-org.proxy.library.nyu.edu/10.1080/11038128.2018.1449888

Fenton, A. T. H. R., Keating, N. L., Ornstein, K. A., Kent, E. E., Litzelman, K., Rowland, J. H., & Wright, A. A. (2022). Comparing adult‐child and spousal caregiver burden and potential contributors. Cancer (0008543X), 128(10), 2015–2024.

Gillett, J. E., & Crisp, D. A. (2017). Examining coping style and the relationship between stress and subjective well-being in Australia's "sandwich generation." Australasian Journal on Ageing, 36(3), 222–227. https://doi-org.proxy.library.nyu.edu/10.1111/ajag.12439

Liu, Y., Wang, W., Cong, Z., & Chen, Z. (2022). Effect of older adults in the family on the sandwich generation's pursuit of entrepreneurship: Evidence from China. Ageing & Society, 42(2), 331–350. https://doi-org.ezproxy.uu.edu/10.1017/S0144686X21001033

Mao, W., Lou, V. W. Q., Li, M., & Chi, I. (2022). Coresidence and well-being among adult child caregivers in urban China: Impacts of the domain-specific caregiver burden. Social Work Research, 46(1), 44–52. https://doi-org.ezproxy.uu.edu/10.1093/swr/svab027

Nieto, A., Contador, I., Palenzuela, D. L., Ruisoto, P., Ramos, F., & Fernández-Calvo, B. (2022). The distinctive role of grounded optimism and resilience for predicting burnout and work engagement: A study in professional caregivers of older adults. Archives of Gerontology & Geriatrics, 100, N.PAG. https://doi-org.ezproxy.uu.edu/10.1016/j.archger.2022.104657

O'Sullivan, A. (2015). Pulled from all sides: The sandwich generation at work. Work, 50(3), 491–494. https://doi-org.proxy.library.nyu.edu/10.3233/WOR-141959

Pope, N. D., Baldwin, P. K., Gibson, A., & Smith, K. (2022). Becoming a caregiver: Experiences of young adults moving into family caregiving roles. Journal of Adult Development, 29(2), 147–158. https://doi-org.ezproxy.uu.edu/10.1007/s10804-021-09391-3

Robbins, R., Weaver, M. D., Quan, S. F., Barger, L. K., Zhivotovsky, S., & Czeisler, C. A. (2022). The hidden cost of caregiving: The association between self-assessed caregiving-related awakenings and nighttime awakenings and workplace productivity impairment among unpaid caregivers to older adults in the US. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 64(1), 79–85. https://doi-org.ezproxy.uu.edu/10.1097/JOM.0000000000002355

Steiner, A., & Fletcher, P. (2017). Sandwich Generation caregiving: A complex and dynamic role. Journal of Adult Development, 24(2), 133–143. https://doi-org.proxy.library.nyu.edu/10.1007/s10804-016-9252-7

Synowiec, P. M., Jędrzejek, M., & Zmyślona, B. (2022). Differences in leisure time across middle‐generation adults in Wroclaw, Poland: Examining the usefulness of the "sandwich generation" category. Family Relations, 1. https://doi-org.ezproxy.uu.edu/10.1111/fare.12676

Citation

Maenpaa, J. (2022). Working with Millennials in the "Sandwich Generation." Continued Social Work, Article 170. Available from www.continued.com/social-work