Editor’s note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Circle Time Success, presented by Liz Moore, M.Ed.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- List two goals for students while participating in circle time

- List two goals for teachers while leading circle time

- Identify two ways teachers can help students actively participate in circle time

Introduction

To start, I want you to take a moment to think about what your circle time looks like. What are some things that you're hoping to get out of circle time? In what ways do you want to make your circle time better? Would you like to improve student participation and engagement? The goal of this course is to provide ideas, supports and strategies so that you can help your students be successful. In addition, I hope this course will help you identify goals for you as a teacher when leading circle time.

Student Goals for Circle Time

Our goals for circle time are different, depending upon the age of the students we're working with. Typically, we would like our students to be able to sit and observe. If we are working with very young children, this goal may be a bit harder to achieve. Additionally, we would want them to be able to attend to the teacher. Another goal for circle time is for our students to gain tolerance for non-preferred activities, as initially, many of them do not understand or value circle time. Also, we would like our children to be able to tolerate proximity of peers, especially for those who may have some social disabilities. For other children, we want them to not only answer questions, but also to ask questions. For some students, it might be that we want them to participate by following along in simple actions, to songs or different motor movements, through imitation. Lastly, we want our children to be able to have some control and to be allowed to make choices in circle time. Sometimes choice making gets a bad rap, and people believe that circle time is supposed to be a teacher-directed activity. However, one common reason why children don't participate in circle time is because they don't feel like they're a part of it. For our children who need a little bit more control, giving them some choice in what happens at circle time can be a great goal.

Teacher Goals for Circle Time

Now that we've talked about what we want our students to get from circle time, what are our goals as teachers for circle time? Many times, I've seen teachers try and use circle time to teach an entire lesson. That is absolutely what we do not want to do. We do not want to teach an entire lesson at circle time or rely on this group lesson to be the sole instruction for the day. Ideally, we want circle time to be a time when we introduce new materials or themes. If you're getting ready to start a new unit (e.g., identifying a new letter of the alphabet), it's a great opportunity to introduce new materials. If a holiday is coming up, like Thanksgiving, it's a great time to begin talking about that. It's also an amazing opportunity to pre-teach ideas. If we're trying to give children a taste of what's to come later, we can hint at what is going to occur in small group instruction or during teacher time, possibly what's going to happen during center times. Finally, it's an opportunity for teachers to be creative and fun. I think a lot of times it's hard for teachers to want to be creative and fun, because they're thinking about the lessons they have to teach, or about challenging students who won't sit still. We need to give ourselves the opportunity to have fun and be creative in circle time, because the more students and children see you enjoying circle time, the more they're going to want to be there and engage and participate. As we go through the presentation, be thinking about the goals that you have for your own classroom.

Key Components of Circle Time

We've identified some goals that we have for circle time, but there are also some important components we need to be thinking about:

- Alternate activities

- Participation

- Choose the right materials

- Provide supports and prompts

- Reinforce, reinforce, reinforce!

- Set the right pace!

Alternate Activities

First, in order to keep students engaged and actively participating, we need to alternate activities during circle time. We don't want our students to be sitting there passively responding or watching. Often, when I go in and help out in classrooms, I see that circle time is a lot of sitting on the carpet and not getting up and moving. One great strategy that's easy to implement is to alternate between sitting and being active or standing. Start by sitting at circle time, and then get the children up and actively moving around.

We also want to make sure that we have specific routine-based activities that we always do at circle time. For instance, every morning at circle time, we might sing the "Hello" song, or we can sing about what we're wearing. Although it is important to keep a routine, we also want to bring in novel activities, such as new songs and books, as well as new units or themes (e.g., if a holiday is coming up). Alternating between routine-based activities and novel activities keeps things fresh.

One that's a little bit more challenging for professionals and providers to implement is giving children a choice of a preferred directed activity that the student directs, and then a non-preferred activity that a teacher directs. If a student isn't necessarily interested in hearing a book or a story, but they love to use musical instruments, think about how we can give them some choice in being able to do a preferred child-directed activity after they've participated in a non-preferred activity.

Alternate between songs and books or literary tasks, such as calendar time and the weather, depending on what the goal of circle time is. We also need to make sure that our children have lots of opportunities for high responding, whether it be through individual students, choral responding, or show me an action or a word that you've written. Alternate high responding opportunities with passive listening activities, such as reading a story, or reviewing what happened the previous day, or what's going to happen next. Make sure that it's not always this passive listening for students; that's how we see our children disengage. Children who aren't native English speakers or children who have communication delays sometimes "zone out" during passive listening. They're not hearing all the valuable information you're providing. When we alternate between all these different activities and tasks, we're going to increase their opportunity to listen, participate, and be engaged.

Participation

Again, participation is going to look very different depending on the developmental needs of the students you're working with, the age of the students, and the topic that you're doing. When we think about participation, for one student it could just be to sit quietly and not be interrupting other students or the teacher. For other children, it could be that we want them to participate by raising their hand and asking questions.

How do we get children invested in participating? We need to make sure each child gets a turn. When you have 20 children, that can be a real challenge. If you have 25 children, it could be an even bigger challenge. We need to have a variety of opportunities to respond, not only as an individual but also as a group.

When you're dealing with children with minimal language, whether it's because they're very young or because they have some developmental delays, we need to provide opportunities for them to communicate and participate. Conversely, when you have children who have a lot of words, you need to allow them the opportunity to shout it from the rooftop and be loud and proud and have those opportunities to respond. There are always ways to get children engaged so that they have different opportunities and different ways to participate.

A child may individually participate by telling her classmates what she wants to sing about today. Another child in the same classroom may be unable to tell the teacher what he wants to sing about. You can give him an opportunity to make a choice. "Do you want to sing about your shirt, your pants, or your shoes?" He may be able to take a picture off of a choice board and hand it to you. If you're singing about clothes, he can hold on to that icon so that he's able to actively participate.

Materials

Another important component to getting children to participate is by the materials used in the activity. Circle time shouldn't just be a time where children are sitting there listening to a story, or watching something on the SMART Board. It's an opportunity for children to explore and hold onto materials. Do we have materials that are individualized for each student? Or are they materials that are for everyone in the classroom? Think about how the materials play a part in the context of what you're teaching.

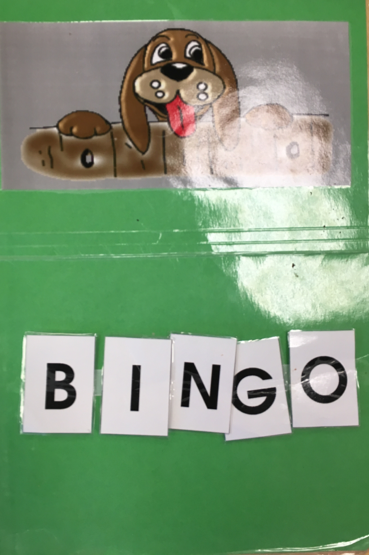

Choose materials that correspond to the context of the activity and the ages of the children in circle, as well as their developmental level. In Figure 1, you can see a picture of a dog and the letters B-I-N-G-O. For our children who can't talk, or maybe don't know the song yet, they're able to follow along by taking off each letter of B-I-N-G-O as the song goes on. That can be a large poster for the entire classroom to use, as well as a small individualized tool for the student to have in his lap so that he's able to participate.

Figure 1. Materials that correspond to the song "B-I-N-G-O."

What does participation look like with these materials? In Figure 2, we see Miss Melinda. She's working on some sight words with students. She has written the word "see." The students have had an opportunity to get out their dry erase boards. They've written the word "see" and they're holding up their boards to show the teacher. Some children are on a level where they're able to do that individually on their own. In the corner, one of the students is needing a little bit more help from a teacher who's sitting behind, providing some supports and prompts so that he's able to be successful. We need to make an effort to meet the children where they are and identify their strengths, as well as the areas where they need more assistance.

Figure 2. Using dry erase boards at circle time.

Reinforcement

The more children are reinforced, whether it's through social praise, a tangible reinforcer, or they're actually motivated and reinforced by the task that's going on at circle time, that will help improve engagement and participation. I feel like sometimes reinforcement gets a bad rap. I often hear teachers saying, "I shouldn't have to do that for that specific student. None of my other students are needing reinforcement." The problem is that reinforcement can work for us, or against us. For example, we may have a student who isn't able to stay at circle time for a long period of time. Maybe he is rolling around on the floor. Maybe he's poking his peer. He's shouting out answers. Overall, he's just being disruptive. What tends to happen is we say, "Okay, Johnny, you don't have to stay at circle time. Go ahead and get up and you can leave." If we do that, we are negatively reinforcing that child, by inadvertently rewarding him for being naughty. That's one way reinforcement can work against us.

When we actively think about how we can use reinforcement in a positive way, then we can make reinforcement work for us. When we individualize reinforcement for students, we are trying to increase responding, participation, enjoyment, and engagement. There are lots of different ways we can deal with this. We can use social praise. We can tell them they're doing an amazing job clapping their hands and stomping their feet during a music song. We could use tangible reinforcers, such as small edible items. Depending on your facility -- whether it's in the school system, a Head Start program, or a childcare facility -- your rules around reinforcement might be different. Make sure you pay attention to the policies and procedures in the facility where you work. Lastly, you can use a specific task or activity that your student enjoys to get them to want to stay at circle time. If they love bubbles, you can blow bubbles to get them to come over at circle time for those itty-bitty toddlers. Or if they love a certain alphabet song, then you can play on the SMART Board or the iPad to get the student to sit at circle time. You can really use reinforcement in a way that increases participation and engagement and enjoyment.

When we are using some type of tangible reinforcer, we want to be sure that we're pairing it with social praise first. And the reason why we want to do that is we don't want this idea of, "I'm always going to give you a tangible item for doing something." Maybe in the beginning, we have to use a lot of tangible praise to teach our students how to sit or to participate, but eventually we want our students to value social praise. When we use behavior-specific praise and tell them exactly what they've done right, we're going to increase the likelihood that that behavior is going to occur. Instead of saying to your student, "Good job, that was great." Say to them, "That was amazing how you sat at circle and crossed your legs." Or, "I love how you raise your hand when you want me to call on you." Or, "That was so great how you clapped your hands when we were singing 'If You're Happy and You Know It'." Tell students the specific behavior that was good, so that they know exactly what they need to continue to do.

The rule I love the most is the 50% rule. Circle it, star it, highlight it on your handout slides. This rule is great across the board when you're dealing with challenging behaviors or when you're trying to reinforce a student for doing a desired behavior. If you have a student who is unable to sit at circle time for more than five minutes, what you're going to do is to cut that time in half. Half of five minutes is two minutes and 30 seconds. We need to be reinforcing our students every two minutes and 30 seconds when they're sitting at circle time. Or, if we're trying to get them to clap their hands four times, we need to reinforce them when they've clapped their hands twice. That's true for any type of activity. If a child is shouting out answers and we're trying to teach them to raise their hand, if they're shouting out answers every seven or eight minutes, cut that time in half by 50% and reinforce them at the three and a half or four-minute mark. You're always going to try and catch them being good. And you can do that by cutting that time in half.

As I stated earlier, we don't always want to use tangible reinforcers. As the student becomes more successful, it's okay to fade away those tangible reinforcers as long as you're continuing to provide that social behavior-specific praise. Reinforcement works best if you have a variety of team members in your room. If you are a lead teacher and maybe you have an assistant or another staff member in the room, it works best if children are reinforced from the teacher who gives their instruction or the teacher who's leading circle time. A lot of times what we see happen is an adult might be sitting next to a student and they will say, "Good job, Johnny, but make sure you're looking at Miss Liz. Pay attention to Miss Liz. Cross your legs." What happens is students begin to pay more attention to the adult sitting next to them because they're more socially reinforcing than the teacher at the front of the room. We want to make sure that the teacher who is leading circle time is the sun, the moon, the stars, the center of the universe. They can do that by giving the instruction and giving the reinforcement.

Reinforcers versus fidget objects. Sometimes, for our children who have attention problems or have a difficult time sitting, we might give them something to fidget with or to sit on and wiggle. We can give fidget objects for children to hold during circle time to increase attending and to keep them present, or we can allow them to sit on a fidget seat to help them wiggle. We really want to make sure that we're giving reinforcers to children for active participation and engagement. If we see that our student becomes so fixated on the fidget object or the wiggle seat or the bouncy ball that they're sitting on, then we need to make sure that we get rid of that fidget object to reduce the distraction. We don't want our children to get too preoccupied that they can't meet the goals of circle time. If that happens, it's time to switch it up and figure out what kind of fidget toy they need. A lot of times, we want the fidget objects to correlate with what we're doing at circle time. When we think back to our BINGO example, that would be a great fidget toy because the child is able to hold onto the letters as the song goes on and they're able to participate. We don't necessarily want to give them something that is going to distract them, like a squishy ball or Silly Putty, because that can become much more reinforcing than participating at circle time.

Supports and Prompts

Next, we're going to spend some time talking about what supports and prompts you can put in place to ensure that your student is able to be successful at circle time. Often, the reason why students don't participate at circle time is because they don't know what to do, or they don't know what's expected of them. Sometimes we have to take it back even a step further and put in some supports so that they're able to be successful.

What are some supports and prompts that you can put in place? Many of our children need individualized help, especially those that are very young. It's important that we provide as much support as necessary. A lot of times, we just assume children should know and they should just do it because we've asked them to do it, or because everybody else is doing it. However, we need to remember if a child could do it, they would do it. They don't want to misbehave any more than you want them to misbehave. I always say err on the side of caution: if they don't know how to do it, let's teach them how to do it. For instance, if a child doesn't know how to read, we teach them to read. If a child doesn't know how to count, we teach them to count. If a child doesn't know how to sit at circle time or make a choice at circle time, or actively participate at circle time, we need to take the opportunity to teach them that skill so that they can be successful. That's where these supports and prompts are going to come into play.

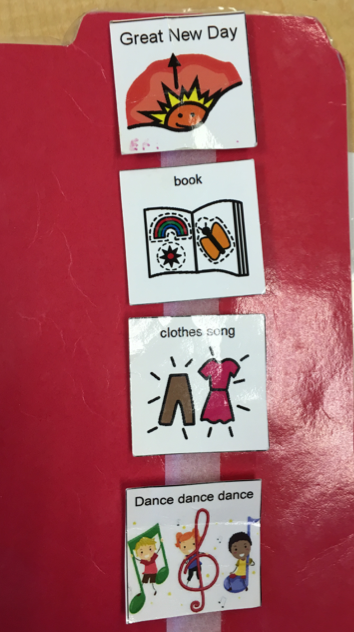

We can use individualized supports, such as visual supports and objects to aid the student in responding independently. We saw some pictures previously of a student saying he wanted to sing about his shoes that day by using his picture. It's not necessarily about children with autism. It could be a child who's a non-native English speaker who doesn't understand the upcoming sequence of events. When we provide pictures for our students to see these individual supports, we're allowing them to know what's going to happen. Imagine if you just showed up to work and you had no idea what your day was going to look like. It can become very overwhelming when you don't know what's coming next. It can be very difficult when you don't know how much you have to do. Individualized supports like this picture schedule (Figure 3) allow our students to know exactly what's going to happen.

Figure 3. Visual support: picture schedule.

We can use prompts and supports to achieve goals and assist our students to respond. I have always felt like as a provider, as a professional, my job is to work myself out of a job. There will always be other children who need me. But by the end of this school year, I want this group of children not to need me. When I provide prompts and supports, I allow them to be much more independent.

Today, we will be discussing the following types of supports/prompts:

- Visual Cues

- Gestural Cues

- Direct Verbal Cues

- Physical Prompts

- Use of Other Adults in Circle

Visual cues. Examples of visual cues are pictures, photos, or a model for a student to see what to do. At circle time, if you have children who don't necessarily respond to a visual cue, you might need to use an object, such as a small book for them to see. If you are going to sing a song using musical instruments, you can use maracas. Visual cues allow our students to see exactly what's going to happen and what to do.

Gestural cues. Using gestures, you can point to the correct response or motion towards an area where they need to go. If you're wanting a student to sit at circle time, you could say, "Sit down," and point exactly where you want them to sit. Or, if you are reading a book, you could ask a student, "Can you show me the pig?" If they're unable to identify the picture of the pig, you could point to it and show them exactly the correct response so that they're able to get it right. We need to have high rates of correct responding because when we have lots of trial and error, we tend to see an increase in challenging behaviors. When I think about challenging behaviors, I don't just think about the child who rolls around on the carpet, runs around the room, and doesn't want to participate at circle time. I also think about the child who disengages and doesn't respond. A disengaged student is just as big of a challenge as the child who's crying and disruptive at circle time. The difference is that the disruptive child is going to get attention much more quickly than the disengaged child. When we provide them the opportunity to fail, we're going to decrease the likelihood that they're going to want to participate.

Direct verbal cues. Tell them exactly what to do or say. You may be working with a student who is just learning to communicate, only having five or six words in their repertoire because they're 18 months old. You might want them to say the word "shoe." Then you could say, "Say shoe." If you are working with a student who is learning English as a Second Language, and you're reading the story "Brown Bear, Brown Bear What Do You See?" and the answer is "yellow duck," then you verbally say to them, "Say yellow duck." Then the student is able to say "yellow duck." The idea is to tell them exactly what to do or say so that they're able to be as successful as possible.

Physical prompting. Using physical prompting, gently (not aggressively) help the child hand over hand. In Figure 4, Miss Arlena is touching her own head, and Spencer is touching a child's head who needs assistance. She is very gently is taking the child's hands and helping the child imitate Miss Arlena. She's using a physical prompt to help her get it right. Miss Arlena is doing the action, and Spencer is silently helping the child to get it right. It's as if she's the silent extension of her body so that she's not able to make that mistake. What's great about this is that the second that Spencer helps the child get it right, Miss Arlena can give her a reinforcer so that the child is more likely to pay attention. When Miss Arlena says, "Copy me" or, "Put your hands on your head," then the child is more likely to do it because she's used positive reinforcement and the child wants access to that social praise and that tangible item.

Figure 4. Using physical prompts.

Using Other Adults in Circle. I've briefly touched on using other adults in circle time. What I have seen happen often, although unintentionally, is that other adults in circle time can be very distracting. They have students sit in their lap. They tell students to pay attention to the teacher leading circle time. They might be playing on their phone and children want to know what they're doing.

How can we appropriately use other adults in circle time? I always say we want adults to sit behind children in circle to prompt them if necessary. Again, it could be very different types of prompts. They could be providing visual prompts, gestural prompts, physical prompts. That's something that you as the professional would want to discuss with the other adults in your classroom, because each student's needs are going to be different, depending on the activity.

If additional adults are in circle time, they should be modeling the actions of the person in the front of the room. If you're singing "The Wheels on the Bus," then the other adults in circle time should be doing those hand movements as well. If they're standing up marching around the room, those other adults should be standing up marching around the room. If it's time to read a story and all of the children are looking up at the teacher with their hands in their lap, the other adults should be doing that as well. The adult shouldn't be whispering, "Pay attention to Miss Liz. Look at the book," because all that's going to do is distract the child. Ultimately, the child will begin to pay attention to the person sitting next to them talking.

Children should be receiving reinforcement or praise from the adult leading the circle time. We want our children to know that at the end of the day, the adult in the front of the room is in charge. They are the center of the universe. If you're using a co-teaching model where you have two teachers in the classroom or two child care providers, depending on the activity, it's important that the students understand whoever is at the front of the room is the important. When I was doing some co-teaching with a speech pathologist, I realized that students were so used to me running circle time and engaging them that when our speech pathologist was up at the front of the room trying to teach a language lesson, they would be turned around trying to engage with me. I had to make a conscious effort to make sure that I wasn't actively engaging students accidentally, and that I was allowing Miss Hall, our speech pathologist, to have all of the attention. When I saw children disengage, I gave her other suggestions of things that students liked to get them to participate. We want to make sure that whoever is in the front of the room is the person giving the children reinforcement and praise.

In the event that a child is trying to talk to an adult who is not leading circle time, the leader should be the one to get the child to reengage. For example: "Olivia, look over here. We're reading a book about bumblebees." Or "Timothy, can you help do the wheels on the bus actions?" Don't rely on the adults sitting in circle time to get the child to pay attention to you at the front of the room.

Pacing

Lastly, how do we set the right pace at circle time? We don't want to go too slow so children are disengaged, but we also don't want to go so fast that children can't keep up and disengage. How do we set the right pace so that all students are able to actively participate? Pacing can be a challenge because if we don't have our materials ready to go, if we don't know what we want to do, we can have a slow pace. When we're thinking about pacing, we want to make sure that we have a quick pace when transitioning between activities within circle time. I tell my staff and my team all the time, "Wait time is death time." Our children will find something to do when they have to wait, which won't be productive and it will be much more engaging and much more reinforcing than what's going on at the front of the room. We want to minimize as much wait time as possible. We also want to make sure that we're alternating between activities to maximize attention.

It is okay to use a slower pace while expecting responses from students with disabilities or English as a Second Language. However, we also want to ensure that we're having a fast pace for our students who have higher rates of responding. When we have children who have slower responses, if we use our prompting strategies (i.e., verbal, gestural, physical) to help them get it right, we can inadvertently increase their pace. I spent some time with an audiologist when I was doing an internship, because I was interested in what we need to do to increase pace and auditory processing needs. If we help our children respond quickly by giving them the correct answer through prompts, then we're going to increase their ability to have a faster pace when responding. Our goal is to be meeting the needs of all of our children. It is okay to modify our pace based on the activity or the student that we're working with, keeping in mind that the pace shouldn't be slowed down because we're not prepared and we don't have our materials.

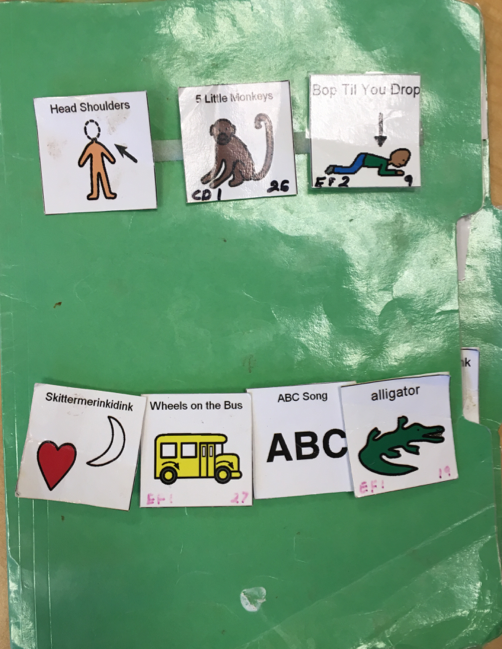

In our classroom, we have three brief circle times instead of doing one long circle time. We have a circle time at the beginning of the day, the middle of the day, and the end of the day instead of having one very long circle. Our circle time in the middle of the day is music time where we use a lot of musical instruments. In Figure 5, you can see all the things that the children are going to be doing during their music time. Using this chart, we're able to quickly go from song to song because we're not sitting there thinking, "Hmmm...I wonder what song I should play next?" I know exactly what we are going to play and in what order the songs should be: Head and Shoulders, Five Little Monkeys, Bop Til You Drop, Skittermerinkidink, The Wheels on the Bus, The ABC Song. We end with a fun alligator song where children get to pass around a stuffed alligator to practice sharing and trading, because that's a great opportunity to bring in some social skills during circle time. If I were disorganized, and if I had to sit and think about what comes next, then my children would get distracted. They'd be disengaged, and I would be continually trying to bring them along with me. What's nice with using these visual supports is that the visual support decides what's going to happen. I don't decide. The student doesn't decide. If you ever need to have someone fill in for you for at circle time, those people even know exactly what they're supposed to do. It's a mini lesson plan for you at circle time. It keeps a great pace; it keeps children engaged and it allows us to minimize the wait time.

Figure 5. Visual supports for music time.

Optimizing Circle Time for Everyone

Timing

I mentioned that we do three brief circles instead of one very long circle. Currently at my school, we have children that range in age from 15 months to four years old. We have a wide range of not only developmental needs, but in general overall needs in terms of how long the children can sit and when they need to get up. When we're looking at time length for circle time, we use the following guidelines:

- For children under the age of 3, circle should be no longer than 6-8 minutes

- For children from the ages of 3 – 3 ½, circle should be no longer than 8-10 minutes

- For children from the ages of 3 ½ - 4 and up, circle should not be longer than 15 minutes

Nothing is more frustrating to me than when I go into a kindergarten or a first-grade classroom and circle time is 30 minutes long. It is hard for me as an adult to sit through a 30-minute staff meeting and actively participate. We shouldn't be expecting our little people to sit and actively participate. If you need to have a longer circle time, either cut it in half and do two circle times, or break it up into three circle times. It should never be a situation where we're expecting our students to sit for long periods of time. It's just not developmentally appropriate, and it's going to promote challenging behaviors and disengagement.

Enticing Students to Join Circle

Many of our younger children don't even know what circle time is, let alone understand the value of it. They just know that they have to sit there when they could be doing other activities that are much more fun, such as playing at the sensory table or at the computer station. Often, we can't even get our students to come over to circle time. I've seen teachers physically pick up a child, carry them over to the circle and force them to stay. We don't want to force children to stay -- we want them to want to come over.

How do we entice our students to join circle time? First, we can allow a student to choose a specific activity, song, or book. We can use bubbles to encourage a student to come over to circle time. I get a little light headed when I blow bubbles for a long period of time, so I purchased a bubble maker. It just continually blows bubbles. Before you know it, all these toddlers are running over. They may not be sitting, but at least they're in the same space. In the beginning, when we're working with very young children, the goal is simply to get them to be in the same space together with their classmates.

Another strategy is to start by reading their favorite book. If the children are in another area, go over to where they are and read one or two pages of the book, then get up and you go over to circle time. Most likely, if they're interested in that book and they want to hear more about it, they're going to follow you. You can do the same thing with their favorite song. If they have a song that they love, you can go ahead and get it started and they might turn and look at you. Then pause the song and see if they'll come over. If they don't, then you could go over and gently lead them by their hand to come to circle time and to participate in that. But in no way do we want to force children to come over and have to stay at circle time. We want circle to be fun and enticing. We want it to be something they enjoy. If we're carrying children over and forcing them to stay, it becomes punishment. It's not rewarding.

Increasing Students' Time at Circle

Maybe you've gotten the student to come over, but they're only there for a brief amount of time. We want to increase the time that they're at circle. How do we do that? If a student has a hard time staying at circle, determine how long they are able to stay at circle time. If you have a student who can only stay at circle time for five minutes, use the 50% rule and cut that time in half, and make sure you're reinforcing them at about the two-and-a-half minute mark, and again at the five-minute mark. While I'm doing that 50% rule, I'm also going to gather all of the preferred items and materials that they love. You may have a student who is new to your classroom, and you have no idea what they like. In that case, I would talk to the parents and get a list of favorite foods, toys, videos and things that they like. Gather all of those preferred items and materials, as well as other materials that similar-aged peers like (e.g., bubbles, Backyardigans, a certain activity on the SMART Board). Gather all of those items and let your student have access to those preferred materials. Or, focus on favorite topics during circle time. If you're working with a child who really loves Mickey Mouse or Minnie Mouse, use Mickey Mouse and Minnie Mouse in your circle time to help them want to stay and participate.

A lot of times, we want our students to join circle time at the beginning. Then, when they misbehave or they can't pay attention any longer, we go ahead and we allow them to leave. Instead of doing that, have the student join the last part of circle and leave with the group. The reason why we want to do that is because we want students to learn that they leave when everyone else leaves, when the teacher dismisses them from circle. But if they get dismissed halfway through circle because of disruptive behavior, they're going to learn that if they continue the disruptive behavior, they get to leave circle time. You're going to be negatively reinforcing that bad behavior. If they can only stay at circle time for five minutes, have them join the last three minutes and gradually increase that time until they're able to stay for a longer and longer period of time. Of course, the longer they stay, the more we need to be reinforcing them. We need to be having a party when they're able to stay past that initial five-minute mark and celebrate the fact that they're able to stay longer and longer at circle time.

Additional Suggestions

During circle time, if you have a child who has a difficult time keeping their hands and body to themselves, provide some visual boundaries of where to sit. For example, you can use carpet squares or maybe you have specific spots on the carpet where they sit. I know that Lakeshore rugs cost a fortune and not everyone has access to carpet squares. The next best thing is colored masking tape. I love colored masking tape because it's cheap and it's not destructive. Just tape off a square where they're supposed to sit, and make it a little bit bigger than most children so that they're kind of staying inside their bubble. As they're able to stay inside the square or the colored masking tape, you can gradually and slowly make the square smaller and smaller until it's the appropriate size.

You may have a child who is passive during songs and stories and books because of lack of language. Provide objects or felt pieces to go along with the story so that they can hold onto them, or that they can give to you as a story is going on. Passive behavior can be just as disruptive as being active and disruptive. The difference is that the passive children tend to get forgotten.

If a child has a difficult time with core strength to sit at circle time, then provide some type of cube chair or a stool at a similar height with more stability. If you're seeing a child wiggle a lot, the first thing I would ascertain is whether they have the physical strength to be able to sit still for long periods of time. If you're seeing that they're unable to do that, providing a chair with some sidebars will allow them to rest their body. My other favorite thing is to use a stepstool so that they're able to sit up a little bit higher and work on that core strength. I would also encourage you to talk to any related service providers, like an occupational therapist or a physical therapist, and they can give you some suggestions for core strength. If we're not meeting the child's physical needs, it will be impossible for them to be able to sit and be successful at circle time.

Case Study: Jackson

I want to take the last few minutes to tell you about Jackson, a little boy that I worked with. When he came to me, he was identified as being typically developing. He was coming to me in my play group. When he did not want to participate at circle time, he would cry. He could only sit for about two minutes. He was unable to participate. The things that his mom told me he loved were the Noggin Goodbye song on YouTube, bubbles, and Goldfish crackers.

In my mind, I immediately started to think what supports and prompts do I need to put in place to help this student be successful? I also wondered what skills is he missing to be able to participate at circle time? When I looked at it in terms of a deficit as opposed to a behavior, I was able to wrap my head around what I wanted to teach him and what supports I needed to put in place so that he would be able to be successful.

The first thing I did was to time how long he could stay at circle. We knew it was two minutes, but our goal was to increase his time to five minutes. As a team, we created a list of what activities Jackson liked and how we could incorporate them at circle time. I asked my teammates and the parents in my classroom to create a visual schedule that alternated between bubbles, a book, and a video of the Noggin Goodbye song. Jackson didn't love books; that wasn't something that was highly preferred. But I wanted to slowly teach him how to tolerate a teacher directed non-preferred task. One issue with Jackson was the second that non-preferred task came, he was up and running and he did not want to participate in circle. Then he was running around the room, crying and being disruptive. He could sometimes get into other students' space and maybe hit them or scratch them. We knew we needed to teach him those skills to be successful.

This is what we did. I would start off circle and I would blow bubbles or I would turn the bubble blower on. Then I would have one of my teammates bring Jackson over to circle time. I gave him the instruction, "Sit down." Then very nicely, very gently, I would use a physical prompt and I would prompt him to sit down. The second his bottom hit the ground, I gave him a Goldfish and I said, "Great job sitting, Jackson; I love how you're sitting." Now if the child is eating Goldfish crackers, it's harder for him to cry, and he's not going to want to get up because why would he leave if he could have access to a food that he really liked? The next thing I did was I read two pages of a book. Each time I turned the page of a book, I gave him a little bit of a Goldfish. Now, after we read those two pages, I showed 30 seconds of the Noggin video. I didn't let him watch the whole video, just a small snippet. Because what we know is if we provide small amounts of reinforcement more frequently, we're going to make that reinforcer much more powerful. I didn't want him to watch the whole Noggin video because when the Noggin video was done, he would want to leave circle. Then I read three pages of the book. In between each page, I gave him a little bit of a Goldfish. After all three pages were finished, I showed him 30 seconds of the Noggin video. I read the rest of the book which is approximately five pages. Then I would give him a Goldfish, and we watched the rest of the Noggin video after that, and then the entire group left circle time. My entire circle time in the beginning was no more than two minutes because I knew Jackson couldn't handle more than two minutes.

Now a lot of you are probably sitting there thinking, "I can't do circle time in two minutes. I'm not going to get anything done." But here's the thing. You're not getting anything done when you're having a child like Jackson run around and be disruptive. You're better off putting the time in in the beginning to teach him what we need him to do and help him be successful than chase him around the room. Before you know it, Jackson was coming over to circle time and he was participating. Then we got to increase what we wanted him to do. Eventually, we could use physical prompts and gestural prompts to help him learn to imitate us at circle time so he could participate in "The Wheels on the Bus." Then we were able to help him learn how to turn the pages of the book so that he was able to participate in the stories we were reading. What started off as a two-minute circle gradually increased to five minutes for him and then eight minutes. It was great because he had no idea of the value of circle time until we taught him that circle time could be fun.

Summary

In summary, circle time is a place for our students to learn, participate, and have fun. Sometimes, we have to meet our students where they are. They may only be able to tolerate two minutes at circle time. They may need physical prompts to know how to participate, or we may need to give them high rates of correct response so they feel successful in participation.

Circle time is not a time to teach an entire lesson, nor is it a time to make children wait. It's a time to have a quick pace and to have active engagement. By utilizing these specific supports that we talked about, we're going to allow our students to engage and participate more. We're going to alternate between activities, such as between music and books, or between individuals responding and choral responding. We need to make sure that we have all of our materials prepared so that we can minimize wait time. When we use those visual supports and those class schedules so children see exactly what's going to happen, then it allows us as teachers and providers to stay on track and on task. It also allows our students to know how much they have to do, what's coming next, maybe when their favorite activity is going to happen, and when circle time is going to be done. Because we're using highly motivating activities (e.g., bubbles, Minnie Mouse, favorite new books, or an upcoming holiday), we're going to see our children want to actively participate and actively engage in circle time.

Citation

Moore, L. (2018). Circle time success. continued.com - Early Childhood Education, Article 22846. Retrieved from www.continued.com/early-childhood-education