Inclusion as a Goal

It is important to start today's course by reviewing the law. The Individual with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) Section 300.114(a)(2) states that every public agency must ensure the following:

"(i) To the maximum extent appropriate, children with disabilities, including children in private, public and private institutions or other care facilities, are educated with children who are non-disabled; and

(ii) Special classes, separate schooling, or other removal of children with disabilities from the regular educational environment occurs only if the nature or severity of the disability is such that education in regular classes with the use of supplementary aids and services cannot be achieved satisfactorily.”

In plain language, that means that every child, regardless of whether they have a disability or not, should be in a neighborhood childcare setting. Whether you work in a public or private setting, you should see kids with disabilities in your setting.

For infants and toddlers, the language is a little different. IDEA Sec. 303.126 states the following:

“Each system must include policies and procedures to ensure, consistent with §§303.13(a)(8) (early intervention services), 303.26 (natural environments), and 303.344(d)(1)(ii) (content of an IFSP), that early intervention services for infants and toddlers with disabilities are provided—

(a) To the maximum extent appropriate, in natural environments; and

(b) In settings other than the natural environment that are most appropriate, as determined by the parent and the IFSP Team, only when early intervention services cannot be achieved satisfactorily in a natural environment."

A natural environment is where that child would normally be, whether they would be cared for in their home, by neighbors, in a family childcare setting, or in a center-based childcare setting. The idea is that all children, regardless of whether they have disabilities or not, should have the same access and opportunities to learn together. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Education came together and published a policy statement in 2015, entitled Policy Statement on Inclusion of Children with Disabilities in Early Childhood Programs. The key points to take from the statement are: It is essential that children with disabilities are included in early childhood programs together with their peers without disabilities; we must hold high expectations; we must intentionally promote their participation in all learning and social activities, facilitated by individualized accommodations. That means we expect great things for all children regardless of whether they have disabilities or not and we individualize for all children. Finally, this statement focuses on using evidence-based services and supports to foster children's development including cognitive, language, communication, physical, behavioral, and social-emotional development. Social-emotional development includes friendships with peers, and a sense of belonging. What we're really seeking to do is to create environments that have high expectations for children, are individualized for children, and that we use evidence-based services and supports to foster their holistic development. Their holistic development includes more than just their academic skills, but also how they're engaging with their friends and how they feel about being in that environment. All of these are critical pieces from the federal perspective of what inclusion looks like.

What is Inclusion?

The Division for Early Childhood of the Council for Exceptional Children and the National Association for the Education of Young Children developed a position statement on inclusion in 2009. They put forth three aspects that guide what inclusion is: Access, Participation, and Supports.

Access refers to providing access to a wide range of learning opportunities, activities, settings, and environments. Participation is when adults promote belonging, participation, and engagement in inclusive settings in a variety of intentional ways. Supports are the infrastructure of systems-level supports that must be in place to undergird the effort of individuals and organizations to create an inclusive environment. These are critical pieces of inclusion.

Scenarios - Is it Inclusion?

Today we will focus on collaboration which comes under the Supports component. Let's start by looking at some scenarios to see how these different components of inclusion come into play.

Mae. Mae is a four-year-old with multiple sclerosis. She uses leg braces and a walker to get around. Her classroom offers her chances to sit in chairs, but they also have a wheelchair available for her when she's tired. Her school building is two stories and has an elevator, but she has to be temporarily separated from her class if they go to the second floor for special classes like motion or for full school activities in the recreation room on the second floor. She also has trouble getting around on the outdoor play equipment, which she really wants to use. Her best friend Elisa likes to climb to the highest part of the equipment, but Mae can't find a way to interact with her when she does. Her teachers want to help her be part of all of the physical play the children do in the classroom, but when it comes to outdoor playtime, they're struggling for ways to help her engage with her peers.

Think about these three components of inclusion: Access, Participation, and Supports and consider how they apply to Mae. Consider Access and ask yourself, "Is Mae in a group with same-aged peers who are typically developing?" She clearly is; she's clearly in a classroom with kids that are her age and she's being encouraged to engage with those kids. For Participation, think about if she is engaged in a lesson with her classmates. She is at times, but when she gets out on the playground and it's outdoor playtime, she struggles a little bit there. For Supports, consider if the teacher has what she needs to be sure her learning is supported. In this scenario, it seems clear that she needs a little more support in helping to figure out how to get Mae engaged with her friends out on the playground. In a situation like this, start thinking about pulling in your collaborating partners, your special education team, particularly the physical therapists and occupational therapists, to brainstorm ways to get Mae engaged in more of the physical play outside. That is one example of how we can start thinking about how a child is included and how we can engage our special education partners to support our efforts at inclusion.

Tina. Tina is a two-year-old with autism. She loves to run, jump, stack and line things up. In the classroom, she does a lot of side by side play with her classmates, but she isn't able to communicate with them and can be easily upset when a classmate interferes with what she's doing. One morning, the teacher set up a sorting activity with bears which Tina decided she was going to line up. When the other children came to and tried to sort the bears, Tina had a temper tantrum and threw the bears on the floor. Her teachers didn't know how to help her calm down and talk about how she was feeling. They also didn't know how to help her understand the sorting activity so she could be part of it.

Let's consider the three aspects of inclusion and see how they're working for Tina. For Access, ask, "Is she able to be with same-age peers who are typically developing?" Yes, she's in a classroom with them. Side by side play isn't that unusual with 2-year-olds, and so it seems like she is definitely accessing the activities and the learning in the classroom. For Participation, ask "Are the child's interactions encouraged?" It seems like Tina doesn't engage and interact as much with her classmates, but they are interested in her and she wants to engage with them. She just doesn't have the tools to do it quite yet. For Supports, ask, "Does the teacher have supports needed to intentionally build opportunities for learning with same-age peers?" From this example with the sorting activity, we know that Tina's struggling and the teachers are struggling to understand how to coordinate it so that Tina can be engaged with her peers. As the teacher, you would call on your early interventionist to brainstorm ways to build interactivity and help Tina understand the task. The early interventionist can help find solutions so that Tina doesn't get upset when the other children are doing what they're supposed to be doing and help Tina move from lining things up to sorting them.

A Team Approach - Requirements

Preschool Requirements

With preschool children, IDEA requires an individualized education plan (IEP).

According to IDEA Sec. 300.321(a), the IEP team for each preschool child with a disability includes:

- The parents of the child

- At least one regular education teacher

- At least one special education teacher/provider

- A representative of the public agency with special education, general education, and resource knowledge

- An individual who can interpret and apply evaluation results

- Other individuals including related service personnel should be included as appropriate

- Whenever appropriate, the child with a disability

The individual who can interpret and apply evaluation results is often a professional who has administered some of the educational assessments to determine whether the child has a disability and how that disability is displaying itself. In the case of Mae, related services personnel would include an occupational therapist and a physical therapist. In Tina's case, perhaps you'll have a behavioral specialist there, and someone who understands autism. There may be an advocate that the family would like to include. Whenever appropriate, the child with a disability should be part of the team. In early childhood situations, they will not be part of the team as they are too young. Later on, when the child gets older, they may be moved into the team, particularly as you're starting to think about transition.

Infant/Toddler Requirements

IDEA Sec 303.343(a)(1) specifies the requirements for infants/toddlers. Each initial meeting and each annual Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP) Team Meeting must include the following participants:

- The Parent or parents of the child

- Other family members as requested by the parent

- An advocate or person outside the family, if the parent requests

- The IFSP service coordinator.

- The evaluator(s) and the people conducting the assessment

- As appropriate, persons who will be providing early intervention services

As part of these teams, it's important to participate in the meetings and coordinate services with the people on the team. Note that the family is part of the team. You are teammates with the parents, family members, as well as all of the other professionals working with that child. Other providers may include therapists, social workers, or mental health professionals, depending on the child. For children with health needs, you may also engage the health provider in conversations about what's going on with that child. Note that if the family speaks in a language other than English, you'll also have an interpreter at all meetings with them to ensure they understand what is being said and can apply it to their everyday life.

Ladder of Inference

When we talk about collaboration and teams, it's important to understand that everyone interprets the world in their own way. Imagine a ladder, and at the bottom of the ladder is Reality and Facts. We all start out with Reality and Facts that we see, perceive and understand. We take a portion of that, which we call Selected Reality, into our thinking and our understanding of the world. Selected Reality becomes the first rung on the ladder. Then, we interpret from there - Interpreted Reality becomes the next rung up the ladder. The next rung is Assumptions, that we make based on our interpretation. The next rung of the ladder is Conclusions. We form conclusions based on those assumptions. From Conclusions, we step up the ladder to Beliefs, and then Actions.

Know that you have your own Selected Reality, Interpreted Reality, Assumptions, Conclusions, Beliefs, and Actions, based on Reality and Facts. Everyone else who works with that child and family also has their own version of this ladder. In talking and working together, you can understand where everybody at the table is coming from and you can find ways to work with each other. I like to think about the Ladder of Inference as a sort of a slice of pie. You own one of those slices and everyone else on the team has their own slice. When you put everything together, you have a complete piece of pizza, something that is wonderful and delicious and great, but it needs all of those different slices to be meaningful. Keep this in mind as you're working with people who may have different understandings of the world than you do. When you work together, there are a lot of different ways that you can work together. There are many approaches and need to pick and choose what will work best for you.

Team Approach Models

There are many models of the Team Approach including:

- Co-teach

- Observe, model, and share strategies

- Work with an Inclusion Coordinator

- Ask for time to coordinate and collaborate with partners

- See if your program has formal agreements with community partners

Co-teach

You may have a good relationship with the early intervention team that comes in and works with children in your classroom. This often happens in the preschools run by public schools. They often are in the same building all of the time and so they have positive interactions. Because they're so frequently together, they can plan together and teach together and develop more of a co-teaching approach. Co-teaching classrooms can be very effective; you can't tell who is the special education teacher and who is the general education teacher. It's very hard to do, but when it does happen it is a seamless way of providing inclusive services. A lot of the community-based preschools use co-teaching because they want to do something that allows all children access to the individualized approaches of both special education and general education.

Observe, Model, and Share Strategies

Another approach is to observe, model, and share strategies. In this version, you take turns watching each other as you're working with children in the classroom. The special education provider will perhaps observe you teaching the classroom. As you model different behaviors, they will perhaps learn from those behaviors and use them themselves. Perhaps they'll help you think about different ways to do things in the classroom. You can both learn from each other and get ideas and strategies to use overall in your inclusive setting.

Work With an Inclusion Coordinator

You also may want to work with an Inclusion Coordinator; that's someone who specializes in identifying the best ways to include a child in your setting. They will observe and offer you coaching and tips for how to better provide services and individualize for children in your classroom.

When I was a preschool classroom teacher, there was an inclusion coordinator who observed me teach a child who had some social-emotional issues. She offered me great suggestions like using a weighted vest and using a technique for calming which involved ripping paper. She gave me a pile of used newspapers and suggested having the four-year-olds rip paper. The sound was appealing to the child that was having issues calming down and the feeling of ripping the paper was incredibly calming to him. It allowed him to get his anger out in a calming, appropriate way that wasn't disturbing to anyone else in the classroom. We ended up using the newspaper for paper mache activities, so it also gave him a sense of being useful to the classroom. It was like he was an extra helper.

Ask for Time to Coordinate/Collaborate with Partners

You can also ask for time to coordinate and collaborate with partners. Much of our day is trapped in doing the various things that we have to do. We don't have time to think ahead, plan, and coordinate with others. It is important to work with the supervisors in your program to find a way to set aside even just half an hour or 15 minutes to check in and coordinate, collaborate, with special education partners and related service providers. I used to meet with an occupational therapist for 15 minutes once per week when I had a child with cerebral palsy in my classroom. It was amazing the amount of information we were able to pass back and forth to each other when we were talking about this child. She gave me some strategies on positioning so that he could sit at the table out of his wheelchair that helped him feel like he was part of the group. Sitting at the table out of his wheelchair allowed him to see the classroom from a different perspective. He loved being out of his chair. Taking that time to sit down with other team members and brainstorm together is really important.

Formal Agreements with Community Partners

Find out if your program has formal agreements with community partners. Those formal agreements go a long way to making sure that what you're able to do is consistent with everyone else in your program and with the special education team. Formal agreements can simplify the process significantly because it is documented and everyone is accountable.

Teacher Roles

What is our role as teachers, and what do we expect from ourselves as we're working in inclusive classrooms? Of course, we want to be engaged with all of the children that we serve and we want to find ways for them to be successful. We don't ever want anyone to feel like they're not part of our group. There are many things that you can do to lead the charge in creating an inclusive environment and making sure that you have the support you need to be successful.

Here are some things that you can do.

Assess and Partner with Families to Refer Children with Developmental Concerns

Several years ago, there was an initiative from the federal government called, Birth to 5: Watch Me Thrive. Its intention was that all early education settings would conduct developmental screenings to identify developmental concerns. If you work in Head Start or Early Head Start, you're already doing that, as it is required through the Act. The idea is that you're constantly looking for red flags or anything that might show that a child needs early intervention services, special education services, or additional support. You would have that conversation with families because you only see that child during the day, and the family lives with that child and may have some similar concerns. It's a process that you and the family are in together.

Engage Children with Disabilities in All Classroom Activities

Engage children with disabilities in every single classroom activity. That means that sometimes you will need to get creative about what those activities look like and what your expectations are for all children in the classroom. It also requires a lot of individualization.

Create Space for Specialists in Plans and Your Room

Create a space for specialists in plans and your room. Make time for them and make space for them so that they have a place to go and something to do in your classroom. In one of the Head Start classrooms that I worked in, the speech therapist led activities for the entire class. She had half an hour every Tuesday and Thursday. She had two or three students that had speech goals on their IEPs and she would deliver those services with the rest of the class. She also did some individual therapy. The fact that everyone in that class had access to those specific activities was a way of making everybody feel included. The children loved her and when they saw her coming, they would go right to the meeting area because they looked forward to the fun activities she had for the whole class.

Identify and Share Strategies to Problem Solve

Identify and share strategies for individualization among partners, including families. When you do a specific activity and use a strategy to individualize for a child that works well, share it with the family and the other partners who are working with that child. They will also share with you. I worked with one child whose parents came up with the strategy of highlighting specific things in books with tactile cues. These helped to keep the child's interest, helped the child to learn to turn pages, and helped the child to get the most out of book reading. They told me about it and showed me some of the books. I started doing it in the classroom and I shared it with the early interventionist. I've been a general education teacher and a special education teacher in center-based settings, and I'm also a parent whose child has received speech therapy, and so I share multiple perspectives because I've held many different roles.

Consult with Specialists to Problem Solve

As a teacher will consult with specialists to problem solve. Issues might come up in your classroom that you can't figure out how to address on your own. Contact the person on your team who has expertise in that area and have them come and help you think it through. An example from my experience is a child who was in a general education classroom who had a lot of trouble behaving. The child may have tantrums, running away behavior, and leave the classroom without permission. The teacher brought me in to solve some of those problems. We came up with strategies to help motivate the child, like using a time interval reward system. Essentially, that means that we kept track of how long he stayed focused and engaged in the activity, and engaged in positive behaviors. We extended the intervals over time. It started with just a couple minutes, then it increased to a couple of minutes more. If he reached those time intervals without any issues, he got to choose a reward. That worked well in keeping him focused and engaged and he had immediate gratification that worked for him. That consultation was critical to the teacher's success in keeping the child on task and keeping his behavior issues at a minimum. I would not have been able to help her if she hadn't asked for help.

Coordinate with Partners to Communicate with Families

Families hear from many different people. We've talked about the different people that are on the team, and that doesn't even include the pediatrician or healthcare provider or other specialists they may be working with that are outside of your program. Coordinate with other partners to ensure that families are always getting consistent messaging from the team and that you are building on one another's strengths and perspectives. Coordinated communication is critical to the role you play in supporting these families.

Division of Early Childhood (DEC) Recommended Practices

The Division of Early Childhood (DEC) Recommended Practices with Examples document is available here: https://divisionearlychildhood.egnyte.com/dl/NRAghl7roM/

You can read through the entire document. One section of the DEC Recommended Practices is focused on teaming and collaboration. There are five standards that are directly focused on working with others when working with children with disabilities:

- Practitioners representing multiple disciplines and families work together as a team to plan and implement supports and services to meet the unique needs of each child and family.

- Practitioners and families work together as a team to systematically and regularly exchange expertise, knowledge, and information to build team capacity and jointly solve problems, plan, and implement interventions.

- Practitioners use communication and group facilitation strategies to enhance team functioning and interpersonal relationships with and among team members.

- Team members assist each other to discover and access community-based services and other informal and formal resources to meet family-identified child or family needs.

- Practitioners and families may collaborate with each other to identify one practitioner from the team who serves as the primary liaison between the family and other teammembers based on child and family priorities and needs.

Special education professionals are expected to be coordinating and collaborating with you as well. The DEC standards focus on collaborating together as a team with multiple disciplines making sure to implement supports and services to meet the unique needs of each child and family; working together as a team to systematically and regularly exchange expertise, knowledge, and information; building team capacity and jointly solving problems; and planning and implementing interventions. Teams are expected to use communication and group facilitation strategies to enhance team functioning and interpersonal relationships with and among team members. They're expected to assist each other to discover and access community-based services and other informal and formal resources to meet family-identified child and/or family needs. Finally, teams are expected to collaborate with each other to identify one practitioner from the team who serves as the primary liaison between the family and the other team members based on the child's and family's priorities and needs. Often there is a service coordinator who takes the lead from early intervention or preschool special education to coordinate with the family. Since you have daily interaction with families, the liaison is your point of contact. You need to be talking to that person on a regular basis because they're going to be able to keep you up to date with that child and discuss challenges that are going on with that child. You can support the liaison and provide information to enable him or her to be most effective.

Teaming and Collaboration Scenario - Mae

Let's go back to Mae, and consider teaming and collaboration as we've discussed today.

Scenario: Mae has multiple sclerosis so she works with a physical therapist and an occupational therapist who are in and out of your classroom activities all of the time. They need to conduct regular therapy with her to make sure she's responding to different interventions. They are offering to support her mobility. Often they remove her from your classroom to work with her. When they do stay in the classroom, they have to have her lay on the floor and use large equipment to practice her physical exercises. The other children may ask questions or try to get involved in the therapy, leaving the learning activities they're supposed to be doing. You've not had many meetings with these individuals, though they seem friendly and interested in making Mae's time in your classroom happy and successful. Occasionally, when you talk with Mae's parents, they tell you some of the things the therapists say to them and they point out when you have said something that doesn't match up with what the therapists have said.

In this scenario, you want to think about the therapists and find a way to understand each other's needs. They need to get certain things done to meet the requirements in Mae's IEP to ensure that she's developing and growing in her physical skills. But you also need both her and all of the other children in the classroom to participate in learning activities and be engaged in the regular flow of the day. How do you sit together and talk about how to make that happen in an effective way? You also need to describe your expectations and adjust them as you get to know each other. As you start meeting and talking about each other's needs, you also need to talk about expectations. You know that they want to engage Mae in that classroom and they want to do therapy there. However, you and the therapists need to find a way to support all of the other children so that everyone feels like they're part of what's going on. Maybe you can talk about ways for all of the children to practice those exercises. You can clear a big space and do motion activities together so that she's doing her adapted motion activity which is the physical therapy or occupational therapy activity, and the other children are doing some kind of exercise or motion activity that parallels that.

This way, everyone is doing what they should be doing at the time and Mae is being included in typical classroom activities. You also want to use communication strategies that work for both you and the therapists and don't duplicate efforts. Mae's parents seem to be the conduit of information at this point and that isn't quite right. You should be getting information directly from the therapists. You need to get engaged in the conversation with them about what's going on and what they're doing. You also need to share information about what you're doing and how it's working for you. Then, ensure that you all are having the same or supportive conversations with the family so that they're getting consistent information. It sounds like sometimes Mae's parents are having to tell you when you're saying something different than what the physical therapist and occupational therapists are saying. You all need to find a way to get on the same page so that you are all sharing the same information. Everyone is well-intentioned in this scenario, and everybody wants the best for Mae and her family. The key is finding strategies that work to bring you all into the conversation and maintain an ongoing positive relationship.

Collaboration Strategies for Teachers

Here are some strategies that you can use. I'm grouping them into five different categories because I think that understanding collaboration in different ways can help you in understanding and taking on the strategies that work for you. You don't need to do this all at once. You can take the part that fits into your routines and your life and then slowly take on more things to build those relationships in a positive way.

Create a Welcoming Environment

Create a welcoming environment for partners. That may include creating a space in the classroom environment for therapy to happen. For Mae, is there a space where her occupational therapist or physical therapist can keep their equipment? Having a space for equipment would make it accessible whenever they're there and accessible to you if you need it. Is there a place for her to lay on the floor and a place for her friends to lay on the floor with her? Is there room for everyone to get together to do a speech and language activity like the one I discussed I mentioned in the Head Start program. What's available to you?

The next thing you want to think about is time for planning. It's one of the hardest things that we try to figure into our day, but time is essential when you're collaborating with other people. You want to make sure that everyone has even just 15 minutes a week to stop in, to share some information and plan ways that you can be supportive of each other. This time allows you to share strategies, maybe plan a whole group activity with a therapist or a special education teacher, and plan time for role reversal. Role reversal would enable you to sometimes work individually with a child while the special education teacher works with a larger group that may include another child with a disability.

Communication, including active listening, is also important to a welcoming environment. Communication should enable you to feel like you're being heard, and also allow related services professionals to feel heard and understood. Creating a welcoming environment means making them feel like they're part of that classroom.

Access to information is also important when creating a welcoming environment. Make sure that you provide team members with lesson planning information, scheduling information, and any child files that they might need to access. You should also have access to their information. One of the best strategies I've seen is to use a binder for the children that are in that classroom with different kinds of assessments, different kinds of notes, anecdotal notations, and information about what everyone in that classroom is doing. It's great for kids with disabilities and great for kids without disabilities. A binder also provides a good record and means of tracking concerns with a particular child, and the development that's happening in the classroom.

Make space in the classroom routines and schedule. As in the Head Start example that I shared, there was a half an hour, twice a week that related service providers provided a lesson that worked for the children on her caseload but also for the entire class. Creating space in classroom routines allows other professionals to do their jobs and also engage with other children in the classroom. It allows the providers to be part of the routines and schedule in that classroom.

Formalize Collaborations

One of the best ways to formalize collaborations is to create a contract. You can do a formal or an informal contract - it can be verbal, or written. In Head Start, they're required to have formal agreements with special education partners and so every Head Start and Early Head Start program will already have detailed collaborations in place. If you aren't working at a Head Start, think about how you could explore developing this kind of contract. It can be an informal process, but having the conversation is critical. Revisiting it on a regular basis helps you clarify and support each other in intentional ways. The contract should define roles and responsibilities, and also what expertise everyone brings to the table. I was trained as a special educator but had many years in childcare and preschool programs before I became a special educator. I was able to see classrooms through both lenses and was able to offer expertise in both areas. The teachers that I worked with knew that they could lean on me for both. Clarify expectations in the contracts so that it's clear what everyone will be doing and what kind of outcomes everyone is hoping for from the collaboration. The formal process allows you to have conversations that you wouldn't have if you didn't sit down and go through this process. Create a collaboration time and describe its purpose so that you're all revisiting how you work together on a regular basis. This also could happen in check-ins, and so ensure that you set time for check-ins.

Participate in Meetings

It is important to participate in meetings. There are lots of different meetings that happen with children with disabilities or those who are suspected of having a disability. There is a child study meeting or evaluation meeting to review the evaluation results and determine eligibility. There is a meeting when you come together and write or rewrite the IFSP or IEP. There is a re-evaluation meeting where you look at the evaluation results again, discuss what is going on with that child and how you can support them. The timing of the re-evaluation meeting will depend on whether you're working with infants and toddlers or preschoolers. In early childhood, transitions are important and involve meetings. It may be that an infant or a toddler transitions into preschool special education services, or a preschooler transitions into a kindergarten setting. You will want to be part of all of these meetings as your participation is critical to the teaming process. You bring in an important perspective of what that child is like on a day-to-day basis and how they're interacting with the general education curriculum.

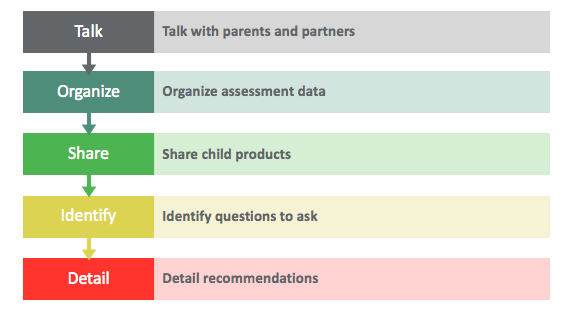

When you're preparing for meetings, you want to do five basic steps (Figure 1).

Figure 1. How to prepare for meetings.

First, talk with everyone ahead of the meeting, so that you know where they're coming from and what their expectations are for those meetings. Organize any assessment data that might be important to helping to understand where that child is developmentally. Share child products to show what the child is doing in your classroom. Child products are a rich way for us to demonstrate growth, particularly if we have samples over time. For example, if you have samples from when the child was three-years-old, four-years-old, and five-years-old, they can help everyone to better understand what has transpired over that time. Identify questions to ask. You may want to help parents identify questions to ask. Then, prepare to come in with detailed recommendations. Think about the things that you want to say and the things that you want for that child.

Communicate Clearly

Communicate clearly and say things in objective ways that convey what you see in that child. Ensure that you are being clear with your audience about what you need from them and what kind of support you need. Conveying yourself in a way that works for you - that may mean taking notes ahead of time, writing bullet points of what you want to say, or even writing yourself a script. You can practice it with some colleagues to see if it is clearly saying the things that you want it to say. Be sure to follow specific confidentiality requirements.

Confidentiality and Communication

Here are some communication methods that you might use to share information within the multidisciplinary team that works with the same child:

- Weekly activity log

- Direct emails

- Shared filing systems

- Online shared file servers (Dropbox, Sharepoint, Onedrive, etc.)

- "Standing meetings"

- On-the-spot communication

When you use online shared file servers, make sure that they're protected so that you're only sharing with the people that have permission to review it. Standing meetings are those meetings you schedule, but they're quick so you stand in a classroom to have a quick conversation about what's going on in your work with the child and family.

On-the-spot communication refers to communication you have in passing with providers about what you're seeing, what they're seeing, and any kinds of challenges that are coming up with a child.

Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA)

FERPA is the law that governs how we share information about children and families. Schools must have written permission from the parent or eligible student in order to release any information from a student's record. Exceptions exist when appropriate. One exception is sharing information among a multidisciplinary team that works with the same child.

In terms of FERPA, what is ok and not ok to share without consent? Lesson plans are ok to share. They are not specific to children, often, and so they're very open-ended and you can definitely share those with your partners. You should share lesson plans so that partners know what you're working on and they can scaffold and build on it when they work with children.

Child records, on the other hand, should not be shared without consent. They should only be shared with written permission or with someone working directly with that child. If a person is written into that child's IEP or IFSP, then they automatically get access to the child records. You wouldn't want to share records with anyone who isn't directly working with that child, including their physician, family health care provider, or anyone outside of your system. You would need to get permission to share the child's records with them.

Can you share on social media without consent? I strongly believe that if you're using social media to share information about children, you should get written consent. You should send home paperwork at the beginning of the year and say, we're going to be using social media this year. If you don't want your child included in our social media activities, please let us know. If you do want your child included, check this box and sign this paper. Keep documentation of consent, because social media is one of those things that can be very sensitive to families.

Direct communication without consent is another gray area. If you're talking to someone who is already working directly with that child and family, then yes, you may have direct communication with them. If it is not a person who's working directly with that child, or you aren't sure if they have written consent to get the information that you would be sharing, then you should not share it.

Who can you share information with, without consent? You can and should be sharing information with special education partners. They need it, you need it, and you both working together on the child's improvement. Do you need consent to share with a mental health consultant or staff that is unfamiliar with the child or family? Yes, you should only share with the mental health consultant or staff unfamiliar with the child and family with the family's consent. You can only share information with people that are documented as being on that child's case. The bottom line is that you need to make sure that you're very careful about who you share information with and how you share it.

Ask for Support

You need to know that you can ask for support and there are a lot of different ways to do that. You can have reflective supervision with your administrators, to talk about how you're including a child, the kinds of things that you're doing, and the challenges that you face. You can consult with mental health and special education consultants and they can provide you with guidance. You can take professional development courses. You can engage a mentor or a coach to work with you and guide you through the process. You can use peer supports or professional study groups. Those are groups of teachers who are also working in similar settings. They get together and talk about what they're doing and what they're learning and the best ways to create an inclusive environment.

Summary

Inclusion requires collaboration and support. Working with others requires planned intentional strategies. Making the effort to build relationships can lead to better instruction and optimal experiences for children, families, and for you. It can improve your feelings about, and experiences in, an inclusive environment. Fred Rogers said, "Mutual caring relationships require kindness, patience, tolerance, optimism, joy in other's achievements, confidence in oneself, and the ability to give without undue thought of gain." Keep that in your mind as you work with new children. Thank you for letting me share this important topic with you today.