Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Play, Has It Become A 4 Letter Word In Education?, presented by Tere Bowen-Irish, OTR/L.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to:

- compare and contrast play-based approaches to learning versus academic approaches for Pre-K and kindergarten.

- apply developmental needs for this age group for collaborative play-based centers.

- examine curriculum standards, taking away strategies to promote play as the conduit for learning.

Play-based Pre-K and K Versus Academic

Play-based pre-K/kindergarten emphasizes:

- Child autonomy

- Academics incorporated through theme-based activities

- Fostering social-emotional growth and relationships

This approach allows children to learn and develop naturally. Play levels match abilities and interests. Bonding with peers and teachers provides critical emotional grounding for the school transition.

Academic pre-K/kindergarten focuses on:

- Letters, sounds, colors, shapes

- Worksheets and structured routines

This model prioritizes measurable outcomes. Rigid standards often pressure teachers, though developmentally inappropriate academics can frustrate and overwhelm young children.

Some states now recognize play as an essential conduit for learning. Play-based models align better with cognitive, emotional, and social needs at this age. Purposeful play teaches vital skills through joy and engagement.

While some capable students thrive with academics, most grow best playing actively. Kindergarten marks a delicate transition requiring nuance, not a one-size-fits-all approach. Playful learning engages children while nurturing essential competencies that enable lifelong success.

Example

- Play-based example

- Go outside, gather materials to make a nest, or use shredded paper. Make nest.

- Use oval-shaped containers or plastic eggs. Have kids see how many fit in the nest.

- Describe and demonstrate how an egg cracks open using crepe paper wrapped around the hand.

- Academic-based example

- See the example in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Example of a bird nest handout.

In a play-based kindergarten unit on birds, eggs, and nests:

- Children gathered materials outside to construct real nests

- They counted plastic eggs placed in the nests, integrating math

- To learn the hatching process, kids wrapped "egg shells" (crepe paper) around their hands and acted out emerging from the eggs over time

This active, multisensory approach engages the limbic system for memory-making - creating a deeper understanding of sequencing than worksheets alone. Making nests and dramatizing hatching brings concepts vividly to life.

A purely academic approach might rely on an egg diagram worksheet. While worksheets have a role, play-based learning engages multiple developmental domains. Hands-on activities make learning tangible while nurturing skills like creativity, problem-solving, and collaboration.

Rather than either/or, the best practice integrates playful activities with targeted academics. Children learn by doing. Purposeful play aligns with cognitive, physical, and socio-emotional developmental needs at this age. Balancing playful learning with instruction meets children where they are.

In Defense of Teachers

While research demonstrates the merits of play-based learning, kindergarten teachers often face top-down pressure for academics. This binds passionate educators striving to follow developmental best practices.

A kindergarten teacher shared her struggle. While she championed play in her classroom, first-grade teachers criticized her students as underprepared. They expected rigorous academics, not the playful approach that built the children's foundational skills.

This teacher's students entered first grade knowing letters, numbers, and sounds - age-appropriate literacy and math skills. However, their play-based kindergarten experience failed to mirror the highly structured routines of first grade.

Misalignment between play-based elementary grades and academic intermediate grades can blindside children. The stark contrast can jar their motivation and self-confidence. Alignment is key for smoother transitions that don't jeopardize developmental trajectories.

Teachers need greater autonomy to balance play and academics appropriately. Blanket academic demands often exceed kindergartners' abilities. Forcing formal instruction too soon backfires behaviorally and academically. Discretion to incorporate play-based learning is essential.

Research Associated With Play

Research reveals diverse cognitive benefits of play:

- Enhances language development through description and comparison

- Improves planning skills by reworking failures

- Can boost academic skills and attitudes through organic interests

- Links to higher IQ scores and socio-dramatic play

- Helps children decenter from an ego-centric view

Play also:

- Provides a release of stress

- Builds confidence and self-assurance

*Taken from the book Playing, a Kid’s Curriculum by Sandra Stone

The hands-on nature of play embeds learning into long-term memory. The multisensory experience - seeing, hearing, touching - creates stronger neural connections than passive learning. An example is the feeling they get when they break the egg, hear the feedback from the materials, and demonstrate inhibition while the egg slowly hatches. Play brings home a concept.

As children build a block tower and discuss its attributes, play integrates conceptual, motor, communication, problem-solving, and social skills seamlessly. Academic skills often emerge organically from play experiences.

Most importantly, play teaches children to navigate challenges while developing self-regulation. The joy and engagement of play promote lifelong cognitive and socio-emotional benefits across domains. It is an essential ingredient of early childhood learning.

Pros and Cons

- In the US, there are more initiatives for kids to learn more at an earlier age.

- Many European countries start much later with academic initiatives…sometimes as old as 6 or 7 years.

- Children learn optimally via play (solid research proves that).

- Children in overly academic programs have more behavior problems than their play-based peers.

- Self-regulation is a predictor of life-long success, with most learned in social environments.

In the US, early academic initiatives are increasing - "kindergarten is the new first grade." However, some European countries like Finland delay formal academics until age 6 or 7, focusing first on play-based learning. Finland boasts one of the world's top education systems.

I sat beside a mother on an airplane who described Finland's play-based kindergarten model, which she highly values. The days include abundant hands-on activities and open-ended play. Teachers gently enhance play by asking open questions like "How could we make this track longer?" prompting children to problem-solve themselves.

Afternoons are spent outdoors hiking, gathering materials, and even using tools like axes - no matter the weather. This immerses students in nature while developing motor skills. The emphasis is on playful learning and skill-building through experience rather than formal academics. Finland's success suggests this developmental approach cultivates capable, resilient learners.

Extensive research confirms play as the optimal way young children learn. However, US studies now reveal more behavior issues in academic kindergarten models versus play-based classrooms. Self-regulation, largely nurtured through social play, critically predicts life success.

Other concerns arise as well. When asked their favorite part of school, most kindergartners answer recess - not academics. Some even name specific literacy programs as their least favorite activity, signaling a potential developmental disconnect.

While capable students benefit from academic challenges, the majority thrive through joyful play-based learning tailored to their developmental stage. Play teaches critical thinking, problem-solving, emotional regulation, and social skills. A rigid focus on academics risks compromising this essential foundation.

Children need activities that engage their abilities and interests in the delicate balance of kindergarten transitions. Play fuels motivation and teaches vital competencies for future learning. Developmentally appropriate play-based learning serves both current and lifelong needs.

Developmental Readiness for Academics

- Since the 1980s, the demands for Kindergarten have been focused on academics.

- “In a survey by Defending the Early Years (DEY) of about 200 early childhood teachers (preschool to grade three) across 38 states, 85% of the public school teachers reported that they are required to teach activities that are not developmentally appropriate for their students.”

- “While the timetable for children’s cognitive development has not changed significantly, society’s expectations of what children should achieve in kindergarten have. A recent two-year study by the Gesell Institute in New Haven found that “children are still reaching important developmental milestones in much the same time frame as they did when Dr. Arnold Gesell first published his data in 1925.”

Play-Based Kindergarten or Academics? | Mrs. Karle's Sight and Sound Reading

Kindergarten's academic demands have increased since the 1980s, even as cognitive development remains unchanged since 1925. Teachers report pressure to instruct beyond students' developmental abilities. This risks frustration and avoidance.

Imagine being forced to perform skills far exceeding your current competence. You might feel intimidated and shut down. Children react similarly when academics overwhelm emerging abilities. Seeing more behaviors or disengagement likely signals developmental disconnect.

Some research suggests rigorous math initially accelerates interpersonal and attentional progress in capable students. But for most, inappropriate demands backfire. Kindergarten requires developmentally mindful expectations as we differentiate instruction based on readiness.

While standards have a place, we must honor childhood. Play teaches foundational cognitive, social, and self-regulation competencies. We can nurture success now and hereafter by meeting children where they are. Kindergarten is no place for rigidity - our flexibility enables theirs.

- “More counterintuitive, to the researchers, were their other findings. In classrooms with more advanced math content, the students displayed stronger interpersonal and attention skills. Advanced language arts instruction didn’t relate to any clear social-emotional benefits, but didn’t seem to harm students, either.”

- “It’s the latest in a string of research highlighting the potential benefits of more rigorous academic content in earlier grades. Three other recent studies focusing on pre-kindergarten, and two looking at kindergarten, have found that students in classrooms with more advanced instruction scored higher on assessments.”

- One consultant isn’t convinced based on the method of teaching

- “Marcy Guddemi isn’t convinced. She’s an education consultant who is on the advisory board of Defending the Early Years, a group that argues against too much academic content for young children and for a greater emphasis on play, which some research has linked to improved physical, social, and cognitive development.”

- “Guddemi notes that the researchers measure academic focus by asking teachers how many days in a month a given skill was taught. They don’t ask teachers how much time is spent on free or academic-focused play, and those can overlap — if a teacher used number blocks to teach math skills, for instance.”

- That’s a form of play,” Guddemi said. “That’s going to enhance the child’s understanding.”

Kindergarten is getting more academic — and the kids are all right. - Chalkbeat

Their other findings were more counterintuitive to the researchers. The students displayed stronger interpersonal and attention skills in classrooms with more advanced math content. Advanced language arts instruction didn’t relate to any clear social-emotional benefits but didn’t seem to harm students either.

This is the latest in a string of research highlighting the potential benefits of more rigorous academic content in earlier grades. Three other recent studies focusing on pre-kindergarten and two looking at kindergarten have found students in classrooms with more advanced instruction scored higher on assessments.

However, one consultant, Marcy Guddemi, is not convinced based on the method of teaching. Guddemi is an education consultant on the advisory board of Defending the Early Years, a group arguing against excessive academic content for young children and for greater emphasis on play. Some research has linked play to improved physical, social, and cognitive development.

Guddemi notes the researchers measured academic focus by asking teachers how many days a month a given skill was taught. They did not ask about time spent on free play or academic-focused play, which can overlap. For example, if a teacher used number blocks to teach math skills. That’s a form of play that likely enhances a child’s understanding.

In summary, recent evidence suggests the potential benefits of more rigorous early academics. However, some experts emphasize the continued importance of play-based learning for development. More research on the right balance of academics and play may be warranted. However, integrating the two shows promise for meeting both academic and developmental needs.

Teacher Style

- Guddemi goes on to say…”Even though they tested higher at the end of kindergarten, that doesn’t mean they learned and are going to retain that information."

- The study also points out that” teachers who focus on higher-level skills may simply be better educators. It is possible that they may be more intentional in how they teach, more motivated to teach the subject matter at hand, better classroom managers, or more adept at fostering a positive social-emotional and learning environment”

- Still, they conclude, “We are cautiously optimistic that advanced academic content can be taught without compromising students’ social-emotional skills”

Another consideration is the teacher's style. Teachers focused on higher skills may simply be better educators overall. They may be more intentional in how they teach and manage the classroom or more adept at fostering a social-emotional learning environment alongside academics.

This warrants some caution. While we can be optimistic about rigorous early academics, we must be careful not to compromise social-emotional learning (SEL). Key developmental theorists like Gesell, Piaget, and Gardner emphasize how interpersonal and intrapersonal skills strongly develop in the early years. How children relate to peers and adults during this time is crucial.

In summary, advanced early academics show promise but should be balanced with play-based SEL. Skilled teachers may intuitively integrate the two. More research is needed on the optimal balance for benefiting both academic and social-emotional development. But completely neglecting either element could be detrimental. The key is likely finding an appropriate level of rigorous academics while preserving ample time for play and relationship-building.

Fostering Learning Through Play: Limbic System

•Attention comes last; their brains will look at relevance and then attend….

Attention comes last in development; children's brains first assess relevance, then attend if interested. Play opens the limbic system and promotes emotional engagement, laying the groundwork for attention and focus. For true attention, children must be interested and emotionally engaged. Their brains judge relevance first and will only then act on what is offered.

In essence, play enables emotional connection and relevance, allowing attention to follow. Completely sacrificing playtime for rigorous academics may unintentionally hamper attention. Children's brains are less primed to assess relevance and attend without an emotional gateway. The key is balancing play and academics so children remain engaged. This emotional foundation motivates learning and allows their attention to flourish.

Quick Idea

Blow up a balloon and write six letters or numbers on it with a marker. Have children bat the balloon around until you yell, "Stop!" Whoever catches it holds the balloon with both hands. Ask, "What letter (or number) is your right pointer finger on?" Then, ask them to name the letter, say the sound, give a word starting with that letter, or state what number it is.

For example, write children's names on the balloon and play with a small group. When they stop batting, ask whose right pointer is on "G" - George may excitedly say, "It's me!" This builds letter recognition and shows how letters make up words. Use 1-10 for numbers and start with basic numeral recognition before asking what number comes before or after.

In this simple balloon play, academics are woven into fun. This builds memory, interest, and emotional engagement - opening their limbic system to learning. It blends curriculum with play, allowing numbers and letters to become more meaningful than rote memorization. The key is integrating academics in a way that taps into children's innate curiosity and excitement to learn.

Reading Curriculum

Sebastian Suggate, a psychology professor in Germany, began studying childhood reading for his doctoral thesis in 2007. His research raises doubts about the effectiveness of early reading instruction. Suggate found no evidence that children taught to read in kindergarten had long-term gains. By fourth grade, their reading level equaled those first taught in first grade.

He considered why focusing so much kindergarten time on reading, leaving little for other activities, when teaching it at age 6 or 7 produces the same outcome by 11. This excessive early emphasis may even be detrimental.

We see this push for early literacy, but outcomes suggest starting later is no disadvantage. I've observed struggling readers excel in kindergarten and then plateau. Or gifted readers comprehend poorly. Environmental factors like ear infections can impede phonetic awareness and unfairly label a deficiency. Expecting all children to meet rigid reading benchmarks with minimal playtime does a disservice. Differentiation and play-based skills serve students better than one-size-fits-all drilling.

In essence, research indicates early reading instruction has a minimal long-term impact. Forcing academics too soon overlooks developmental readiness and variations. Kindergarten should nurture the whole child. Reading can be gently fostered through play, not mandated as rigid skill drills. This more balanced approach supports later achievement without sacrificing social-emotional needs.

Sample Curriculum- Pre-K

- Pre-K

- Exposure to the alphabet: letter names and sounds

- Recognize, spell, and write first name

- Hold a pencil, marker, and crayon correctly

- Retell familiar stories

- Draw pictures and dictate sentences about stories and experiences

- Answer questions about stories

- Repeat simple nursery rhymes and fingerplays

- Phonological awareness: rhyming, syllables, alliteration

Typical kindergarten literacy goals include letter recognition, spelling and writing one's name, proper pencil grip, story comprehension and retelling, drawing and dictating sentences about stories, answering questions, reciting rhymes and fingerplays, and phonological awareness.

Movement activities like the "drive-thru" game can reinforce these skills interactively. For example, a teacher begins the alphabet, and students finish it. Then the teacher mixes up the sequence - starting at "L" and having kids continue "M, N, O..." This engages the mind and body. Students can also act out butterflies while saying letter names.

Rhyming boosts literacy, too, but classic nursery rhymes are vanishing. Children delight in rhyming through motion. With "windshield wipers" for the "it" family, a teacher says, "Bit, B-I-T, bit." Students shout, "Sit, S-I-T!" by substituting the first letter. This shows how words fit together through sounds.

The key is balancing literacy goals with developmental needs. Motion, music, and play build skills implicitly, keeping young brains engaged. Worksheets or drills shouldn't dominate. Kindergarten should nurture the whole child - creativity, social skills, fine motor, and academics intertwined for joyful learning. This integrated approach gives equal weight to literacy and development.

Figure 2 shows an example of a Drive-Thru Menu activity card.

Figure 2. Drive-Thru Menu "Mouse Ears" activity card.

Dr. Alice Gopnik

- "The preschool years, from an evolutionary point of view, are an extended period of immaturity in the human lifespan.”

- “But it is during this period of immaturity that exploration and play take place. Ultimately, exploration and play during preschool turn us into adults who are flexible and sophisticated thinkers.”

“If you look across the animal kingdom, you’ll find that the more flexible the adult is, the longer that animal has had a chance to be immature.”

Dr. Alice Gopnik highlights the evolutionary role of extended childhood immaturity in humans. During this prolonged period of exploration and play, crucially, our brain develops the flexibility for sophisticated thinking. Open-ended play, without a rigid structure, enables learning in myriad ways suited to each child's individual pace and style.

As Gopnik notes, across species, longer immaturity equates to greater cognitive agility in adulthood. Animals with the most flexible adult abilities had the most play-filled youths. In humans, our unusually protracted childhood opens a window for boundless developmental play unavailable to other species. Far from being idle, such unstructured activity sculpts neural pathways key to later innovation.

Ample time for imaginative play and hands-on discovery is not a luxury but an evolutionary necessity. It allows young brains to create nuanced neural maps before adulthood's pressures set in. Curtailing play prematurely risks hampering the very abilities that enable human adaptiveness. Our childhood plasticity is precisely what nurtures adult flexibility. Play is learning in its most exuberant, enduring form.

Sample Curriculum- K

- “With prompting and support, ask and answer questions about key details in a text”

- “Students will be able to retell key details”

- Know number names, count sequence

- Compare numbers

- Identify and describe shapes

- Classify objects and count the number of objects in each category”

Here are some ways to integrate play into kindergarten academics based on the examples provided:

- Use classic nursery rhymes and have students act them out. For Little Miss Muffet, one child is the spider crab walking towards another child squatting as Miss Muffet. This builds sequencing, comprehension, and coordination. This can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Drive-Thru Menu "Little Miss Muffet" activity card.

- Incorporate math with nursery rhymes, too. For Jack Be Nimble, put candlesticks (blocks) in a line and have students jump over, comparing candlestick heights and counting how many they jump over.

- Let kids choose roles and repeat rhyme plays at recess for enjoyment. This imagination and pretend play boosts their social-emotional development.

- Be cautious about banning playlike behavior (e.g., stick guns) without providing an outlet for those feelings. Children need a safe space to act out their anxieties. Completely denying this imagination can be counterproductive.

- Blend required skills like retelling key details, counting objects, and sequencing events into play. This activates their engagement and motivation to learn.

In summary, nursery rhyme reenactments, sequencing games, and imaginary play provide the joyful practice kids need to build academic and developmental abilities. They make learning active and fun, not passive and dull. A balanced approach addresses standards through play rather than excluding play.

Play Acting

- It is largely imitative and helps the child appreciate that one thing can be two things at one time.

- This helps with perspective-taking and imagining being someone else, the hero or the villain.

- Researcher John Byers discovered that the amount of play is correlated to the development of the brain’s frontal cortex.

Research demonstrates the multifaceted developmental benefits of imaginary play acting for young children. According to researcher John Byers, more play correlates with enhanced growth in the prefrontal cortex, the brain's center for self-regulation and inhibition. Dramatic play also builds perspective-taking as children appreciate that one thing can be two things at once. Embodying characters allows them to safely act out anxieties and gain empathy for others' experiences. Socially, pretend play teaches crucial interpersonal skills like collaboration and relationship-building. Cognitively, reenacting stories boosts comprehension, language, and creativity as well. Play-acting works like a full brain workout that strengthens executive function, emotional intelligence, and narrative abilities. Robbing children of play deprives them of this invaluable opportunity for holistic learning and growth. Imaginative play lays the neural groundwork for self-control, social adeptness, storytelling, and flexible thinking.

Justifying Center Work

I once observed preschoolers deeply engaged in imaginary play with blocks as "video game controllers." When I asked to join their game, a child handed me a block to use as my controller. I enhanced their play by pretending to be a character moving around inside the block structure "TV." The children loved this new twist and begged for turns being the character. This shows how adults can build on creative play rather than interfere.

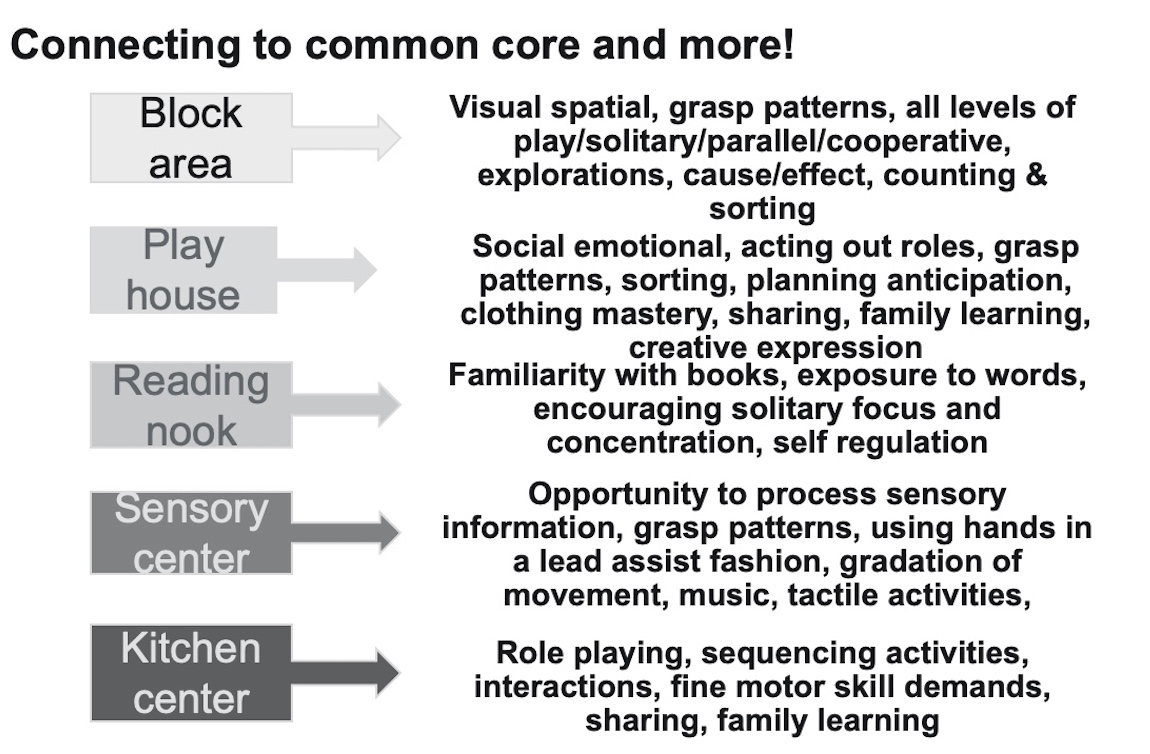

Some misunderstand the value of play centers like kitchens or block areas. But these spaces provide crucial learning opportunities. Some examples are in this chart in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Skills worked on in centers.

Blocks build visual-spatial skills, patterning, counting, cooperation, and more. Dramatic play areas allow role experimentation, emotional exploration, and social interaction. Sensory areas facilitate tactile and kinesthetic learning. Play materials tap into diverse learning styles.

Tragically, some schools prioritize narrow academics over enrichment centers. One kindergarten had its kitchen playset discarded due to apathy about play-based learning. This represents a great loss of inclusive, developmentally meaningful experiences.

Play provides an optimal context for skills like literacy to unfold naturally. For example, in reading nooks, children develop familiarity with books and words through self-directed exploration. Play creates motivation to learn rather than passively receive instruction.

In summary, open-ended play cultivates foundational abilities - executive function, perspective-taking, communication, and regulation. These capacities cannot be rushed but require time and space to bloom. Play is the fertile soil where key developmental milestones put down roots. An integrated approach nourishes children in all facets of their growth.

Stuart Brown: PLAY, How It Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination and Invigorates the Soul

- “The properties of play are:

- Apparently purposeless

- Inherent attraction

- Voluntary

- Freedom from time

- Diminished consciousness of self

- Improvisational potential

- Continuation desire”

Far from being purposeless, play fundamentally shapes and nourishes the developing brain. As researcher Stuart Brown explains, play opens the imagination, forges creativity, and draws children back through sheer enjoyment. The improvisational nature of play builds executive function as kids improvise new uses for materials. Play fires the brain's reward system, so activities feel intrinsically motivating rather than imposed. With play, process trumps product - children feel free to explore, build, and paint as the spirit moves them. This fluidity promotes cognitive flexibility over rigidity. Play also benefits adults as a vital respite from stress. Carving out time for playful engagement enhances innovation, adaptation, and well-being across our lifespan. Play synchronizes mind and body through sheer joy in the moment. It unleashes new neural connections that fuel inspiration, self-direction, resilience, and fulfillment. Play awakens our most resourceful, refreshed selves.

Vivian Gussin Paley: A Child’s Work, the Importance of Fantasy Play

- We must ask ourselves as we plan for school time, are lesson plans that include paperwork, skill, and drill going against what is natural in children?

- “There is no activity for which young children are better prepared than fantasy play.”

- “Fantasy play provides the nourishing habitat for the growth of cognitive, narrative, and social connectivity in young children.”

Researcher Vivian Gussin Paley aptly describes fantasy and dramatic play as a fertile habitat nourishing children’s development. When kids transform ordinary objects through imagination, like turning a block into a remote control, it sparks creative thinking and symbolic representation. Enacting dramatic narratives promotes perspective-taking, sequencing skills, story comprehension, and language growth. Socially, pretend play teaches crucial lessons in cooperation, empathy, and conflict resolution as children navigate interpersonal dynamics and rules. Cognitively, socially, and emotionally, pretend play enables holistic learning. As kids bring stories to life through dramatic reenactment, explore social roles, and use creativity to reinvent reality, they experience visceral joy and awe. Through active play, this integrative process strengthens imagination, cognition, communication, and emotional intelligence. Fantasy and improvisation supply the nourishing habitat where these essential abilities take root.

Where Can We Promote That?

- Dramatic play might be a good area…

- Also celebrating the awe of learning, taking time to ask how kids are feeling about the play, their experiences, their challenges, and triumphs.

- Day-to-day living allows us to practice skills to handle compromise, disappointment, negotiation, and repair. We need to supply the coaching, facilitation, and time to promote awareness and learning.

When introducing play centers to young students, the center itself should be the main attraction. For example, one kindergarten teacher set up a yoga center with five yoga cards that allowed five students to participate simultaneously. Each child picked a card and had to teach that yoga pose to the group. Next, they drew their favorite pose from the activity. Finally, they copied the letters spelling the pose's name to integrate literacy. This playful approach made yoga engaging, as evidenced by students spontaneously acting out poses from books read aloud in class. The anecdote illustrates how play enhances learning, a natural process ingrained over centuries of human development. The main ideas are that play centers should attract interest, incorporate different learning modalities through hands-on activity, allow peer teaching, integrate drawing and writing to support literacy and tap into children's innate impulse for play. Though potentially disruptive, play boosts engagement, comprehension, and development.

Learning Enhanced By Play

"You can discover more about a person in one hour of play versus one year of conversation.” Plato

Block Play

- In summary, playing with blocks may help children develop the kinds of skills that support later learning in science, technology, engineering, and math.

- Problem solving, working with others, and collaborating are all the results of what we might consider “simple.”

- Some research suggests that spatial skills also improve.

- Promotes hypothesis, cause and effect, leading to basic scientific reasoning.

Ten Things Children Learn From Block Play | NAEYC

Here are the key points about how block play supports learning:

- Block play helps develop skills that form the foundation for STEM learning later in life. It facilitates problem-solving, collaboration, and spatial abilities.

- Manipulating and constructing with blocks allows children to explore cause-and-effect relationships. This builds basic scientific reasoning and logic.

- Although playing with simple blocks may seem trivial to some, research shows it cultivates crucial cognitive capacities. The hands-on trial-and-error nature of block play is how young minds intuitively learn.

- Spatial skills, collaboration, problem-solving and scientific reasoning are not niche abilities but core competencies. Block play strengthens these in a developmentally appropriate way.

- Open-ended block play encourages creativity, planning, persistence and imagination. The benefits span across cognitive, motor and social-emotional domains.

In summary, block play provides full-brain learning. Its interactivity and simplicity invite endless exploration of how objects relate in space, gravity and balance. This hands-on discovery fuels young children's comprehension of the physical world while having joyful fun. High-tech toys have limits, but simple blocks offer timeless, multidimensional learning.

Puzzle Play

Association for Psychological Science. (2015, January 28). Playing with puzzles and blocks may build children's spatial skills. ScienceDaily. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/01/150128131323.htm

- “Play may seem like fun and games, but new research shows that specific kinds of play are actually associated with the development of particular cognitive skills. Data from an American nationally representative study show that children who play frequently with puzzles, blocks, and board games tend to have better spatial reasoning ability. Being able to reason about space and how to manipulate objects in space, are a critical part of everyday life, help us to navigate a busy street, put together a piece of furniture, and even load the dishwasher. And these skills are especially important for success in particular academic and professional domains, including science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM).”

“In addition to finding the importance of spatial learning in improving understanding of the number line, the team also showed that a better understanding of the number line boosted mathematics performance on a calculation task.

Puzzle play can promote stronger reading skills by improving visual-spatial abilities. Assembling puzzles involves manipulating pieces spatially to complete the overall picture. This spatial reasoning helps develop skills to visualize how symbols on a page fit together into meaningful words and sentences when reading. Researchers have found connections between puzzles, blocks, and board games with enhanced spatial cognition in children.

One teacher saw this link between spatial learning and math skills. She created a giant number line from shower liners for students to hop along, calling out numbers as they landed. This full-body engagement allowed them to concretely experience number sequences and practice addition by hopping from one number to another. For example, a student would roll dice, land on 2, and then hop 6 more spaces from 2 to reach 8. The kinesthetic number line brought abstract concepts to life, providing an "aha" moment to build early numeracy.

The anecdote illustrates how puzzle play can translate to math and reading gains by training spatial abilities. Hands-on spatial activities make academic skills more concrete and intuitive for young learners.

Combined Interventions

The Snowy Day

By Ezra Jack Keats

- Here's what we did:

- Pretended to shovel

- Pretended to put on our clothes to play in the snow

- Walked different ways to make prints

- Pretended to push a stick in the snow on a tree

- Threw imaginary snow balls

- •Built a snowman…

The kindergarten class deeply engaged with The Snowy Day through immersive play experiences. After discussing the feel of snow and its link to ice cubes, students pretended to shovel "snow" in the classroom using yardsticks, struggling to grip their mock shovels properly. They practiced sequencing winter clothing by layering items in order, realizing boots go on after snow pants. A dressing relay race tested their speed.

The class walked in different styles to mimic animal prints in snow - penguin waddles and frog leaps. Reenacting a scene, students shook tree branches and fell over as "snow" dropped. The crashing delighted them. For indoor snowball fights, some classes used newspaper balls, and others had store-bought fake snowballs.

Finally, each class built large 3-part snowmen using stuffed white garbage bags. They decorated their snowmen with accessories and facial features. This creative collaboration integrated concepts of size order, winter clothing, and body parts. The children immersed themselves in the book's world through dramatic play, movement, games, and art. The active engagement facilitated comprehension of the story while concretely developing academic and motor skills.

The Mixed-up Chameleon

By Eric Carle

- Here's what we did:

- Walked like the different animals

- Decided what two animals we liked best

- Played with words to name our animals…a dog and cat mixed might be a dat or a cog

- A horse and kangaroo might be a korse or a hangaroo!

- We drew them to see what characteristics our new animal would have.

Reading The Mixed Up Chameleon prompted creative movement and art explorations. Students embodied animals by slithering like chameleons. Choosing two favorite book creatures, they invented combined names using phonics, like "dat" for dog and cat.

The children then drew their hybrid animals, blending distinctive features based on preferences. One boy depicted dog traits but rejected a cat tongue, explaining his distaste for them. His artwork had a large drooping dog tongue instead. Other examples included "korse" and "hangaroo" mixes.

The teacher integrated more phonics play during daily transitions. Using the letter of the day, she altered students' names for routines like 10 am snack time. Tere became "Barry" with a B. Ian transformed into "Bian." The word manipulation enlivened functional tasks while building literacy skills.

The class actively immersed themselves in the book through dramatic character movements, collaborative mergers, and invented phonetic names. The playful extensions provided meaningful practice with phonics, creativity, physical control, and social interaction.

Transportation Curriculum

- Here's what we did:

- Made a “car or truck” out of a shoe box with a string. Kids loaded the shoebox with numbers, characters or picture cards and delivered them to the teacher or to match others on the table.

- We drove our bodies around, gathering numbers of items called out by the teacher.

- We laid on our backs and “bicycled” and counted out how many miles we rode and what we saw.

- We drove matchbox cars around numbers.

To immerse students in transportation concepts, the class engaged in playful academic activities. Kids decorated cars with headlights, doors, and license plates using shoeboxes. String "steering wheels" let them drive around the room.

The teacher tossed letter cards on the floor and gave each student a letter to find, differentiating help as needed. I playfully pulled over speeding student drivers as the therapist, issuing gentle warnings. Their pretend play brought the concept to life.

Other activities included bicycling on their backs, counting "mileage," and describing scenery. Matchbox cars drove around number shapes. The transportation unit provided interactive learning anchored in curriculum standards through games and imaginative play. Students created their own cars, maneuvered them through various tasks, and roleplayed community driving roles. The multisensory experiences deepened comprehension and skill application.

Conclusion: Eliminate the Worksheet

- Work collaboratively with other educators or yourself to figure out how to bring home a concept with hands-on experience! It could be letters, numbers, or other curriculum standards that you may find on your state's Department of Education website.

Worksheets have a place in early childhood education but should be used thoughtfully. I once consulted on a 4-year-old boy struggling in preschool. His teacher said he had sensory issues and couldn't access the curriculum. However, I observed age-appropriate play and motor skills at home.

At school, he was asked to independently complete a letter B worksheet, tracing lowercase B's with just a pencil and paper. He gripped the pencil tightly and pressed hard in frustration. I explained that this fine motor task exceeded his skills. More developmentally appropriate activities like gluing beans into B shapes would better engage him.

We must enhance worksheets to make learning playful. Expectations should match children's developmental capabilities to prevent unnecessary frustration. While some students excel, comparing everyone else to the top performers sets many up for failure. Developmentally inappropriate demands likely contribute to rising behavioral, social-emotional, attention, and regulation problems. Kindergartners now hate school, though learning was more organic and play-based just a century ago.

For kids with special needs, you want to coach play interactions, tailor activities to their abilities, use dyadic play, and avoid assuming prerequisite skills. Districts should also reconsider teaching only lowercase letters first if research shows capital letters' benefits for writing automaticity. Learning should be playful and match developmental stages to optimize engagement and success.

References

Ajzenman, H. (2020). Occupational therapy activities for kids: 100 fun games and exercises to build skills. Rockridge Press. Emeryville, CA.

Dearbury, J., & Jones, J. (2020). The playful classroom: The power of play for all ages. Jossey-Bass Books.

Figueroa, L. P. (2019). Therapy in the great outdoors: A start-up guide to nature-based pediatric practice with 44 kid-tested activities. Outdoor Kids Occupational Therapy, Inc. Berkeley, CA.

Gillen, G., Hunter, E. G., Lieberman, D., and Stutzbach, M. (2019). AOTA’s Top 5 Choosing Wisely® recommendations. Am J Occup Ther, 73(2):7302420010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2019.732001

Jirout, J. J., & Newcombe, N. S. (2015). Building blocks for developing spatial skills: evidence from a large, representative U.S. sample. Psychological science, 26(3), 302–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614563338

Liebenrood, S., & Theimann, R. G. (2021). Kindergarten ready through play: 75+ play-based learning activities for toddlers & preschoolers. The Literacy Connection.

Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process—Fourth Edition. (2020). Am J Occup Ther, 74(Supplement_2):7412410010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001

Taylor, M. E., & Boyer, W. (2020). Play-based learning: Evidence-based research to improve children’s learning experiences in the kindergarten classroom. Early Childhood Educ J, 48, 127–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-019-00989-7

Citation

Bowen-Irish, T. (2023). Play, has it become a 4 letter word In education? Continued.com - Early Childhood Education, Article 23859. Available at www.continued.com/early-childhood-education