After this course, participants will be able to:

- Explain how to integrate Positive Discipline Tools into classroom management strategies.

- Describe how to use Positive Discipline Tools to teach social and emotional life skills.

- List the goals of challenging behaviors.

Introduction and History

I am excited to be here today and share information and tools from the book I wrote and developed with Jane Nelsen, the founder of Positive Discipline when I was working in a preschool with three, four, and five-year-olds. The book, Positive discipline tools for teachers: Effective classroom management for social, emotional, and academic success, is a great resource to supplement this article. I had the opportunity to test these tools firsthand, not only in the classroom but also in supporting teachers implementing these tools. I have also used these tools at home as a parent from the time my children were toddlers and through their teen years now.

First, I want to give you a little history about positive discipline. Alfred Adler and Rudolph Dreikurs developed the theory of Individual Psychology. I will talk a little bit more about each of them and their influence in schools and early childhood education as we go through the course. Jane Nelsen and Lynn Lott are the founders of Positive Discipline. There are over 20 books now about positive discipline across developmental ages for parents and for classroom teachers. Jane Nelsen was a young mother with a house full of children. She decided she needed to take an early childhood education class. The focus in that class was on Alfred Adler and Rudolph Dreikurs' work. She found the tools so helpful that she continued her training and her graduate work, became a school counselor, and then in the 1980s wrote the first positive discipline book.

Jane Nelson and Lynn Lott met at one of the Adlerian conferences in North America and started working together to develop the experiential activities that are the focus of all our trainings in positive discipline. These tools are taught to parents, early childhood educators, and teachers through grade 12 all over the world. There are trainers in 62 countries. What I have found personally most helpful after studying Adlerian psychology in graduate school was that the experiential activities and the very practical tools that we will cover today helped me really apply and watch teachers be able to apply what we have known for decades from Adler and Dreikurs' work and the research, what really helps in taking challenging behaviors and building life skills from them.

Behavior Challenges

Positive discipline provides a roadmap for you. When working with young children in the classroom we often see challenging behaviors. Positive discipline helps us take these challenging behaviors and shift them to opportunities to teach. Take a minute or two and jot down recent challenging behaviors over the last year that have either stumped you or created a feeling of frustration as you work with young children. A couple of examples of challenging behaviors might be biting or not listening.

Here is a comprehensive list of things that we have found that routinely come up for educators and parents when we ask, "What are challenging behaviors?" This list comes from all over the world, including China, Latin America, Europe, and the United States.

- Won’t listen

- Interrupting

- Backtalk

- Throwing

- Biting

- Pushing

- Off task

- Fighting

- Defiance

- Strong-willed

- Name-calling

- Lying

- Tantrums

- Grabs toys

- Crying

It is interesting that sometimes when we say, "They will not listen," it is really that they are not doing what we ask. Instead of getting stuck in these challenging behaviors, we like to use these as opportunities to teach. Shifting from being stuck in the stressful moment of the challenge to developing characteristics and life skills is the longterm goal of positive discipline.

Now I would like for you to take a few moments to jot down characteristics and life skills that you would hope that children you work with would develop longterm. When I work with parents I say, "Imagine that your young child, at 25 years of age (because that is when the brain is fully developed) is coming to your doorstep to surprise you on a special event, maybe your birthday. What is it that you would hope and aspire for the longterm?" Again, all over the world when we ask this of early childhood educators, teachers of older children, and parents, we see routinely the same comprehensive list. The characteristics and life skills we wish for the children that we work with include:

- Self-discipline/accountability

- Responsibility

- Communication and problem-solving skills

- Respect for self & others

- Empathy, compassion

- Self-confidence and courage (risk takers)

- Desire to cooperate and contribute

- Self-motivation to learn

- Honesty, sense of humor, happy

- Healthy self-esteem

- Flexible

- Resilient

- Curious

- Belief in personal capability

All these characteristics and life skills are valued across cultures all over the world, regardless of language, background, or socioeconomic status. Nowhere on here do we ever see listed straight As. It is really about character development and life skills and the ability to self-regulate and monitor and use self-control and problem solve as an adult. This is really fascinating to us, and we find it very hopeful that we can take challenges and work to develop life skills using positive discipline tools.

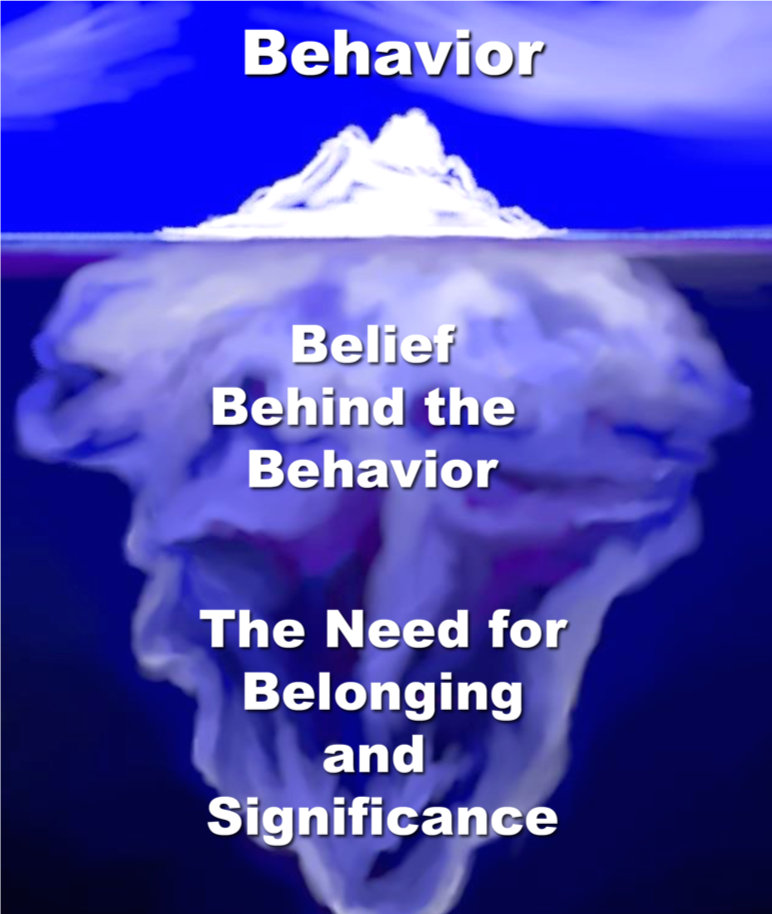

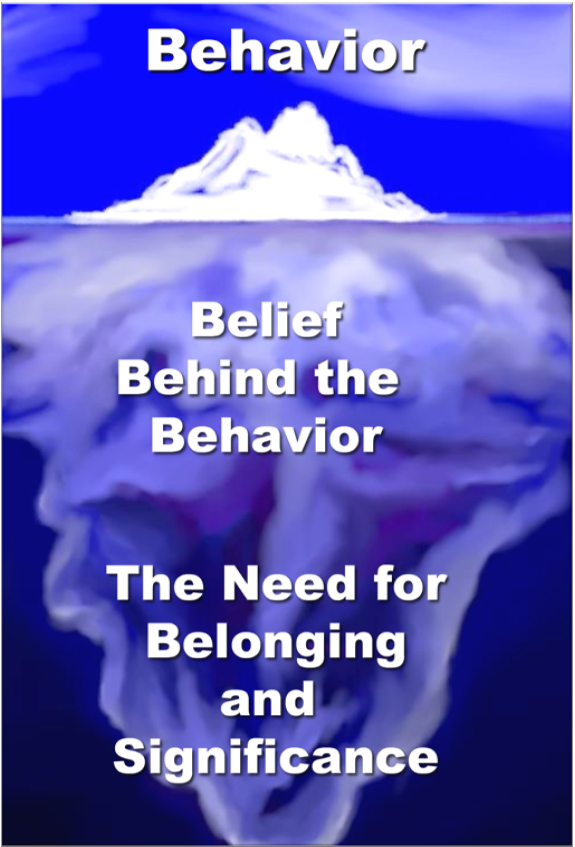

Figure 1. Behavior iceberg, from www.positivediscipline.com.

Figure 1 shows an iceberg that we will use to delve deeper into how positive discipline works to help you avoid rewards and punishment and learn more about what the research says of why punishment and rewards do not work long-term. In Adlerian psychology, there is an understanding that the challenging behavior is just the tip of the iceberg. Beneath the water's surface, there is the belief behind the behavior and the need to belong and feel significant. This is a fundamental, innate human need. When children misbehave, it is the tip of the iceberg that is the challenging behavior that we see. If we chip away at that tip of the iceberg, ignoring what is underneath the water's surface, we might make the tip, that misbehavior or challenge, even worse. Instead, we need to recognize that and work with tools and strategies to help adjust the belief behind the behavior and the need for belonging and significance.

What the Research Says

Research tells us that if we use rewards and punishment to chip away at that tip of the iceberg, punishment might work in the short term, but the behavior usually worsens, the child will avoid the punisher, or things will morph into something different. With rewards, we know from the research that over time, intrinsic motivation deteriorates when rewards are used.

Human beings have an innate desire to contribute. When we have belonging underneath the tip of the iceberg without contribution, that can equal entitlement. In today's world children might not have to work at home as hard or do chores or work on the farm or do different things to contribute because there are so many automations and things that make life simple. Everyone is going so fast and there is a tendency to contribute less. I want to point out that a major focus in our book is that if a child is developing belonging by having too much done for them or by being pampered, then the belonging will shift to entitlement. We really want to focus on helping children feel belonging through contributions. We will go through very specific positive discipline tools for the classroom to help this.

One study that I find extremely fascinating involves toddlers and altruistic behavior. In this study, the researcher is in a room with the mother and her toddler. The mother is placed in a corner of the room in a chair to observe. The toddler is left to play and go about the room on his or her own and then the researcher, organizing the room and creating the circumstance, drops a folder or a clothespin while trying to hang up a piece of artwork in the room. In each instance, the toddler, without hesitation, goes without direction or adult instruction and helps the researcher pick up the piece of paper. Next, the researcher has his hands full, trying to get into a file cabinet when the door will not open. Again, when the researcher is bumping up against the file cabinet, not saying anything, the toddler stops his or her play consistently and goes to help. To me, this is fascinating research because it shows that innate ability and intrinsic motivation in young children to help and contribute. From that contribution is what develops that sense of belonging and connection that brings about encouragement to do well. Usually, when we feel a sense of belonging, there is less misbehavior.

Dreikurs said we never do for a child what he or she can do for themselves because we are in a hurry or to help it goes more smoothly. When we do it for them, we squash that sense of "I can do it myself" and that sense of natural wanting to contribute and help. That has been a rule of thumb for me as an educator and as a parent, searching and stepping out of the situation and consistently assessing what young children can do developmentally for themselves. I try to make sure it is appropriate for them to do or take time for training and allow them to do everything they can possibly do for themselves to let that sense of capability and personal power help drive them forward. Because of this, I see fewer challenges and more of those life skills and positive characteristics that we listed a few minutes ago being developed.

Specific Tools for Contribution

Two very specific tools for the classroom that help with this developing the sense of contribution are classroom jobs and agreements. These are handled a little differently in a positive discipline classroom. For example, with agreements, educators often get frustrated or upset with young children because they are not going along with the agreement, but they were not involved in making the agreement. As early as developmentally possible, we want to involve students and very young children in coming up with the agreements. We want to draw forth from them so they are involved, see the reason, how it helps the group, and ask them for help in making the agreements. I have done this with hundreds of groups of young children, and by late twos and early threes they come up with the exact guidelines we need for our classroom that we as teachers would come up with ourselves. Examples include hands to self, looking eyes, listening ears, and quiet voices. When we draw from them and involve them in coming up with the agreements, it is much more likely that they will contribute and go along with the agreement.

First, we want to involve children in the process of what agreements and class guidelines are, and then we want to involve them in helping each other and the whole group to follow the agreements. There are also classroom jobs. Traditionally, you walk into most preschool classes and early childhood centers across America and even internationally and there is a bulletin board with die cuts about class jobs. These are often assigned. Again, the more we can get children to come up with what jobs need to be done the more there is going to be that sense of contribution and involvement. Both these help build community in the classroom and will help avoid misbehavior. It is also helpful to have the list be a fluid list that can be added to or taken off based on time of year and the needs of the group.

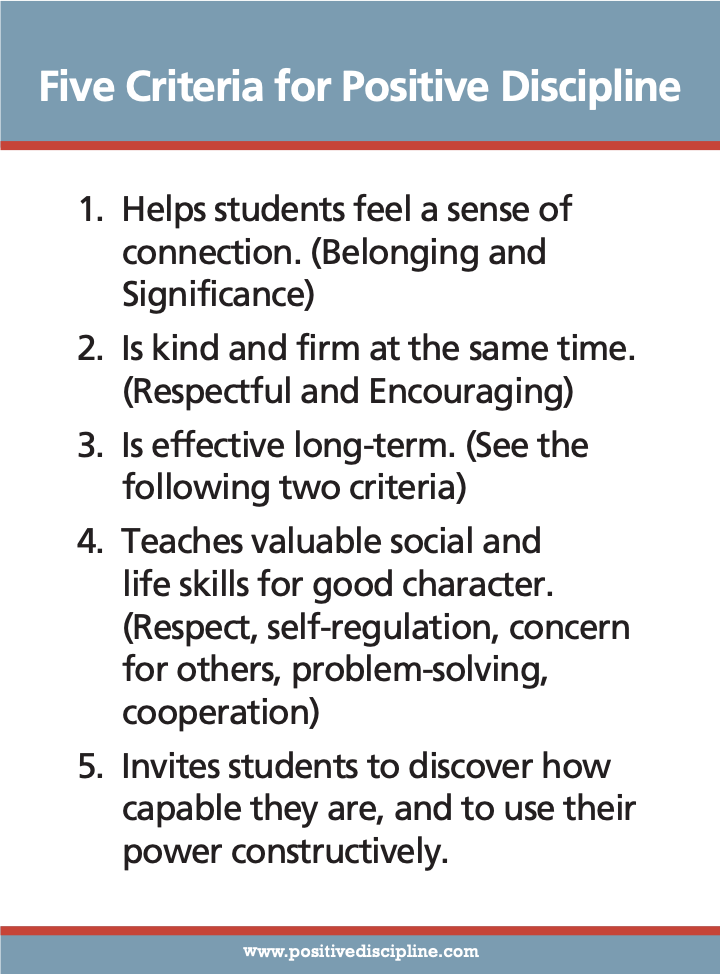

Five Criteria for Positive Discipline

There are five criteria for positive discipline as seen in figure 2. We will hit on each of these in just a moment, and then go deeper into what the research says, and how longitudinal studies show why these criteria are so important. Every tool in our book, as well as all the tool cards, follows these five criteria. They help students feel a sense of connection and belonging or significance, through contribution, not entitlement. Positive discipline is focused on being kind and firm at the same time and being respectful and encouraging. We are looking at long-term effects. When I work with educators or parents, I am often told, "Well, I put this punishment in place and it worked," or, "I used this reward." We are never going to say that that is not going to work short term, but I always go back to what are those long-term life goals and characteristics and skills that we want to be teaching children?

Figure 2. Five criteria for positive discipline, from www.positivediscipline.com.

Everything we do in positive discipline is focused on long-term and teaching those valuable social-emotional life skills for good behavior: respect, self-regulation, concern for others, problem-solving, cooperation. Finally, each tool invites students to discover how capable they are. Instead of getting into power struggles during playtime with their peers or with a teacher or even a parent, we are putting a structure in place to help them use their power constructively.

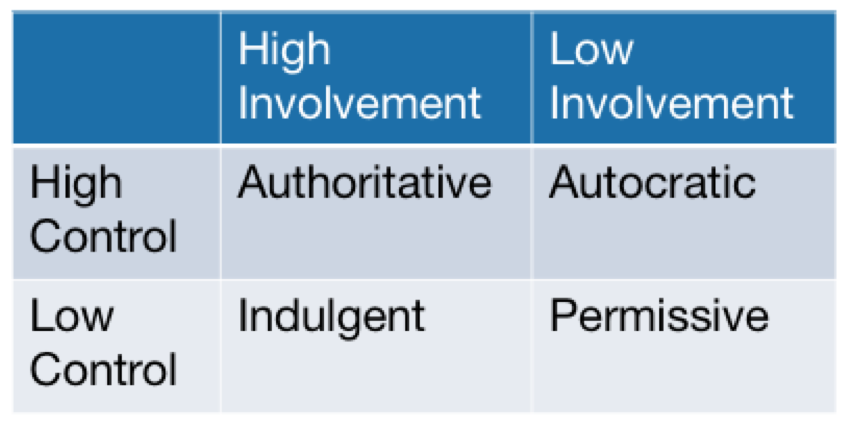

Figure 3. Teaching styles by Wenning (2004) and Baumrind (1971).

I am always fascinated by the research about this. For my dissertation, I studied parenting and teacher leadership styles. Diana Baumrind, from the University of California at Berkeley, is a leader in this area. She did fascinating research starting back in the '60s and '70s looking at leadership styles at home and school. Figure 3 shows the results of some of their research. What we see in the United States is a pattern across several decades where we started off very autocratic with low involvement and high control. One person at home was usually the boss and one person at work was usually the boss. There was a firm structure of leadership autocratic in nature. Then in the '60s and '70s, it switched, very much, to laissez-faire and more permissive, with coming back, and what Baumrind's research and others have shown is that authoritative with high involvement and high control combined is what is effective and optimal child development long-term.

This is the part of positive discipline, being kind and firm at the same time, that helps each of these tools be so effective. We are kind to build that relationship and that involvement, and we are firm to put the structure and the sense of control in place for the environment to help children feel safe and succeed. Authoritative leadership style is characteristically warm and nurturing (kind and firm). Children express their views, but appropriate limits are set. The authoritative style is most closely associated with consistent, appropriate student behavior. The authoritative style encourages independent problem-solving. The separate, completely independent body of research supports not only positive discipline strategies in the classroom but also, all of Alder and Dreikurs' work since the late 1800s.

Specific Tools

Next, we are going to do an activity where you will read through a list of directions. Think about or reflect on the ideas presented here. First, I am going to ask you to be in the role of a young child. Pick the age group that you work with frequently and imagine yourself in the shoes of the child. Read through the statements then reflect on how you felt and what you thought as you read them.

- Go get your jacket.

- Wash your hands before snack.

- Lie down on your mat.

- Share with your friends.

- Put the blocks back on the shelf now.

- Don't throw the toys.

- Don't take beans from the sensory bin all the way into the kitchen area.

- Go get your things from your cubby.

Now, in the shoes of that child, and from that child's perspective, take a moment to reflect on what you were thinking, feeling, and deciding in that role.

Next, I want you to read a different set of statements, all related to the same topic the teacher was involved with each of the students in the last list.

- What will you need to take so you will not get cold outside today?

- What do you need to do with your hands before snack time?

- Where should you be so you can rest at nap time?

- How can you and your friends play with the toys together?

- Where did those blocks go?

- What do you do when you finish playing with them?

- Toys in the classroom are not for throwing.

- What can you throw, and where can you do that that is safe?

- Where do the beans go?

- What do you need to get from your cubby before you go home for the day?

Again, just take a minute in the shoes of that child to reflect on what you were thinking, feeling, and deciding as you read those different asking statements.

If we are doing an experiential workshop and we are live, we have participants take on the role of young children, with an adult reading these things to them, and then we take time in the workshop together to process, as I asked you to do. We discuss what we are thinking, feeling, and deciding at that moment in the role of the child. Often, our tendency is to resist when we are being told. Neuroscience supports this.

Telling vs. Asking

Telling invites "Do as I say" as well as resistance and blind compliance. It prevents independent thinking, critical thinking, and the child does not learn to problem solve. Often, telling invites those challenging behaviors we listed in the beginning, while asking, on the other hand, invites skill development, which is our long-term goal. It invites cooperation, at least most of the time. I am going to say upfront, not every positive discipline tool works with every child in every moment. That is why I am very relieved there are so many. Asking allows students to develop critical thinking skills, it encourages independence, and it helps students learn how to problem-solve.

When my two boys were two and four years old and my daughter was born, this tool was a gold mine for me. When I was trying to get the two and four-year-old out the door for preschool before it was time for nap time for the baby, all I had to was ask, "Where are your shoes? What do we need to do next," and they would self-direct. I saw this real first-hand, work, and also in classrooms across many different settings. It is a great tool.

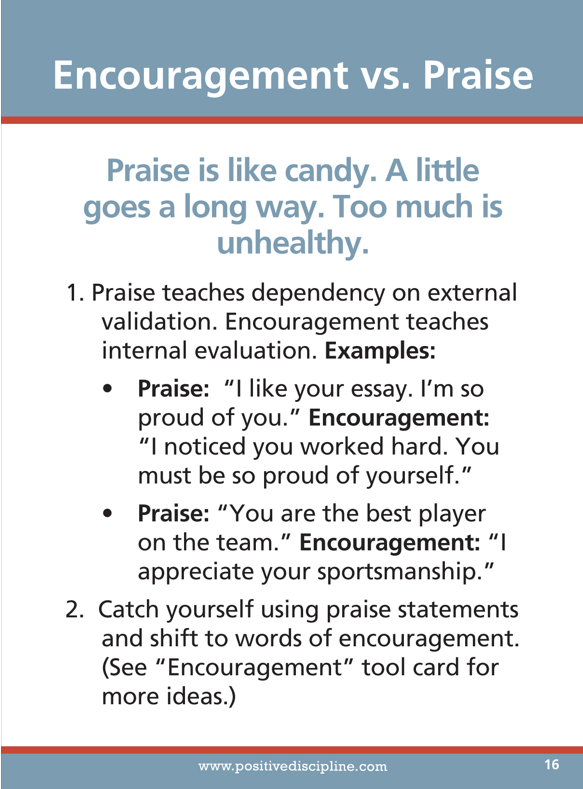

Encouragement vs. Praise

Figure 4 shows the tool card for encouragement versus praise, which is my favorite positive discipline tool. It is important to understand the difference. We are a praise-focused culture. Praise is like candy. A little goes a long way, and too much can be unhealthy. It is almost an automatic reflex for adults to praise young children. Knowing the difference between what encouragement versus praise can do for children is so important.

Figure 4. Encouragement vs. praise, from www.positivediscipline.com.

Praise can teach dependency on others, while encouragement focuses on capability. I want you to work over the next week to catch yourself when you praise because you always will. See if you can turn it around to an encouragement statement that focuses on something specific, the effort the child is making, or even the emotion you see on their face. It is harder than you think. I do not want you to be discouraged by trying to shift from praise to encouragement, but it is really important, because it helps influence our children's development of grit, and the statements they say in their head to themselves.

Remember, encouragement will invite self-evaluation while praise invites children to become approval junkies and come back for more and more. One of my peers in graduate school gave an example that I really felt helped capture this concept. If you put the spotlight on a child with praise, then when you walk away you take that spotlight with you. However, when you use encouragement, and that is the spotlight, it goes deep and it sticks. When you walk away, the encouragement stays with the child. This is a simple shift of words. Here are some examples of that shift.

Praise: I am so proud of you."

Encouragement: "You worked hard. You must be so proud of yourself."

Praise: "I liked your picture."

Encouragement: "Look at all the colors you used. Tell me about your picture."

If you are working with children, you will catch yourselves many times a day using praise statements. Just simply catching yourself and following up with focus on effort or process or specificity can help.

I am going to tell you a story about myself. As an Adlerian play therapy student, I was in a classroom with a one-way mirror where my whole job was just to practice encouragement and get feedback from my professor and peers. I did a great job. At the time I was a mother of young children. When I was through I went to pick up my own children from preschool. My son put a beautiful picture in my hands, and I quickly caught myself saying, "Oh Bryce, I love it." I caught myself and followed up and asked, "Tell me the colors you used, how did you decide?" and "Tell me what you like about your picture?" That shifted the conversation so it would go deeper. Praise is not bad. Again, it is like candy. It is just shifting to a little bit different language where we are focusing on effort and what the child is experiencing rather than our adult approval.

Carol Dweck's research is fascinating to me. She was at Columbia and is now at Stanford. She has done decades of research with preschoolers, all the way through working with her graduate students. She has focused on the impact of praise on students and found that students who were praised for being smart when they accomplished a task later chose easier tasks. These students did not want to risk making mistakes. On the other hand, children who were encouraged for their efforts chose more challenging tasks when given a choice. To me, this has such an impactful message for educators, especially early childhood educators, about what a simple shift in language can do in terms of motivating students. Encouragement that focuses on the student's effort provides a variable the student can control. Students come to see themselves in control of their success. To encourage others, focus on effort, improvements, contribution, enjoyment, and confidence.

I am always asked, how do you remember to use these important words? One thing that helps me is to shift from, "I like," to "I notice." This makes it more neutral, and again, it causes the child to draw forth inside, just like asking versus telling does. When you focus on effort, improvements, contribution, enjoyment, and confidence for the child's experience, that helps you to use encouraging words.

One thing that also has helped teachers as I have worked with them over the years is just to practice changing some simple statements. The following statements are all praise statements.

- I like your picture.

- I am proud of you.

- You are a great helper.

- You are so smart.

- I like the way you are always on time.

Take a moment to see if you can shift these five praise statements to statements of encouragement.

Below are some examples of how you might change the praise statements to statements of encouragement. The more you can point out how a young child is influencing the group in a positive way, the better. Some of these are tiny shifts in how things are worded.

| Praise Statements | Statements of Encouragement |

| I like your picture. | Tell me about your picture. |

| I am so proud of you. | You must be so proud of yourself. OR Tell me how you did it. |

| You are a great helper. | The way you helped pick up all the blocks helped the group get to circle time quicker. |

| You are so smart. | Wow, I see you working really hard. You finally got it. That must feel good. |

| I like the way you are always on time. | I notice you are always on time. OR It really helps the group when you are on time. |

Here are more examples of encouragement.

- You figured out how to do that.

- Wow, you did it!

- You are learning how to tie that shoelace. Last week you had trouble getting it tied, but this week you did it without a problem.

- Tell me how you did it.

- I see that you are working hard.

- This is hard for you, but you are sticking with it.

- You searched your mind and came up with something new.

Positive Time Out: Cooling Off

Now I want to shift to another great positive discipline tool, cooling off. My favorite quote from Jane Nelsen is, "Where did we ever get the crazy idea that in order to make children do better, first, we have to make them feel worse?"

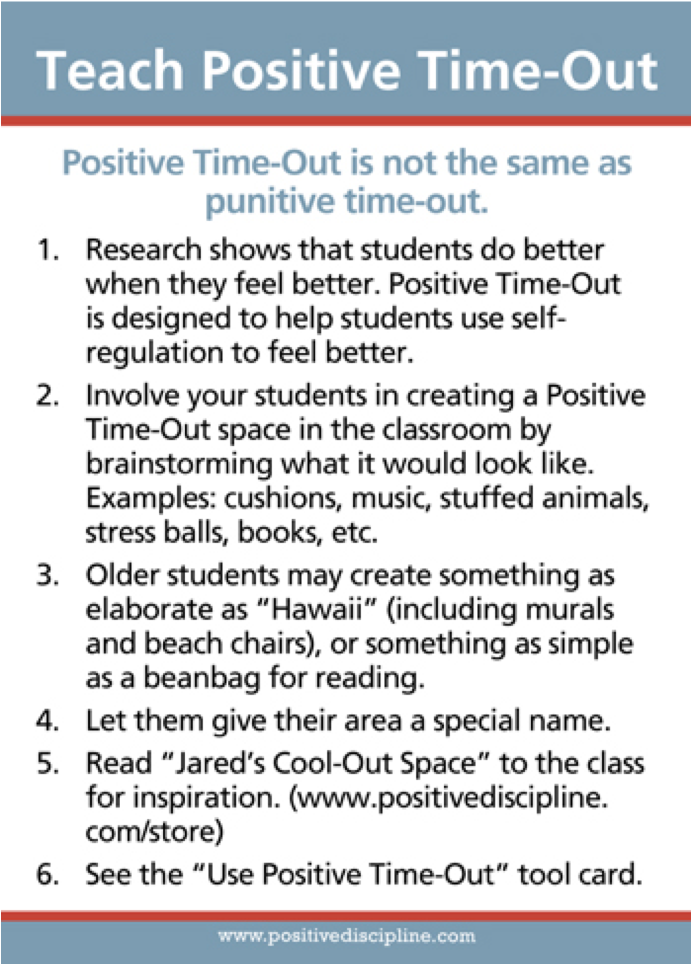

Positive time out was developed by Dr. Nelsen in response to reading about punitive time out. There is so much research now that shows punitive time out increases the emotional reaction or strengthens the power struggle when an adult tries to make a child go to the corner or sit on the bench, especially for young children under two. We need to bring them in to help them self-regulate. The positive discipline tool of cooling off is about making sure that children feel better so they can do better. It is about teaching self-regulation skills and learning to cool off before we problem solve. It is important to teach this, and we advocate involving children as soon as they are developmentally able. This can be by involving them in the process of designing a pleasant area (cushions, books, stuffed animals) that will be a place they can go to help them calm down, self-regulate, feel better, and then as a result do better!

We cannot just use positive time out without teaching the value of it. If children are too young for that process, we want to bring them in to help them calm down, put them in our laps, help them breathe with us, and count slowly, even if they are not verbal yet, to help them calm down. Talk with them about how we want to get calm and how when we are calm our face and our stomach feel different. Figure 5 shows the tool card for teaching about positive time-out.

Figure 5. Teach positive time-out, from www.positivediscipline.com.

Jared's Cool-Out Space is a book that helps teach this to young children. It was written by Dr. Jane Nelson and Ashlee Wilkin, a kindergarten teacher. It is about a little boy who comes home from school and he has dropped the pottery dish that he made for his dad's birthday. He comes in and slams the door, kicks the table, and bursts into tears. His mom uses great positive discipline tools of empathy, validating feelings, but then sets limits. She takes time for connection before correction, and together they come up with the idea that it would be great for Jared to have a corner in his room to help him calm down and cool off. He uses a cardboard box to create his space. In the book, Jared has the opportunity to practice this when he is upset because while making a card for his dad he spills paint all over it. There are great feeling faces in this book to help young children understand strong feelings and how to calm down.

When I have worked with young children in groups, as early as they can talk, I often ask them, "What helps you feel better?" or, "When you have strong feelings or feel like you are going to snap like a spaghetti noodle, what helps you calm down?" As soon as they have words, they often say, "My lovey," "My mommy's lap," or "Hugs." The more we can focus on using that innate ability of a child to know what they need to calm down before they problem solve and find a solution or do a repair, the better.

Research

Let us take another moment to talk about what the research says. Research using brain scans at the Mindful Awareness Research Center shows that negative effects of isolation during a traditional time out brings about the same brain chemistry as physical punishment. Eisenberger, Lieberman, and Williamson used neuroimaging to examine how social exclusion is similar to physical pain. Their study showed that in brain scans, the chemical response is the same. These findings show how the neuroanatomy of a child being excluded or made to sit in a traditional time out causes the same chemical reaction as physical pain.

Human beings innately need to connect and belong. When young children are having trouble managing their emotions, or they feel discouraged and misbehave, giving them the tools to first calm down to feel better so they can do better is a lifeline. Adler said the cornerstone of mental health is the ability to assess the needs of the situation and others and act accordingly. We can teach young children to take a step away, deciding to do that on their own or start to do it with an adult and then learn it in the classroom. Over time, they will start to feel better, learning self-regulation and emotion management. Then they can work with the teacher or the peer they had the challenge with, or the whole class in a class meeting, to help them better get control of themselves, have that self-control, and be able to problem-solve.

Understanding Children's Behavior: The Iceberg Analogy

Next, it is really important for us to understand more about the iceberg and the purpose and goal of misbehavior. Figure 6 shows this iceberg analogy we saw earlier. Dreikurs and Adler pointed out that children make decisions based on their perceptions or their private logic from a very early age. First in the family, and then in their very first school experiences, they are sizing up do I belong, and am I significant in meaningful ways? They are making decisions that are centered on this need to belong and feel significant. When children feel safe and connected, they feel a sense of belonging and significance.

Figure 6. The iceberg analogy, from www.positivediscipline.com.

On the other hand, when they do not, you often see challenging behaviors at the tip of the iceberg. We want children to thrive. When children do not feel a sense of belonging, they adopt survival behaviors or misbehaviors, what we see as the tip of the iceberg challenging behavior. These behaviors are based on mistaken ideas about how to find belonging and significance. Dreikurs called these mistaken goals because they are mistaken ways to find belonging and significance, or get adults' attention. Dreikurs identified four goals of misbehavior: undue attention, misguided power, revenge, and assumed inadequacy.

Dreikurs' Four Goals of Misbehavior

What really helped me in my first school experience after my master's program and before I had young children was to focus on my adult feeling when there was a challenge with a young one. When I was in the classroom and there was a challenging moment, thinking back on exactly what my feeling was helped me understand the purpose or the goal of the behavior.

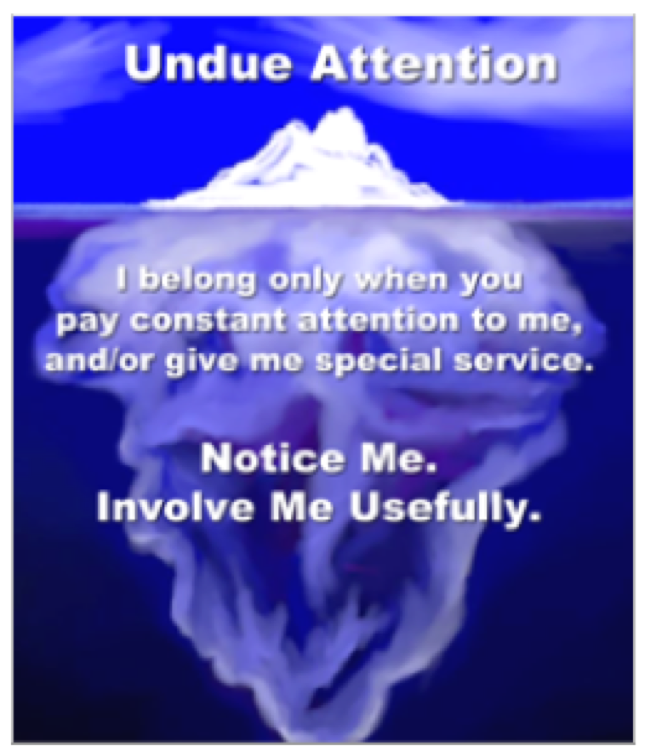

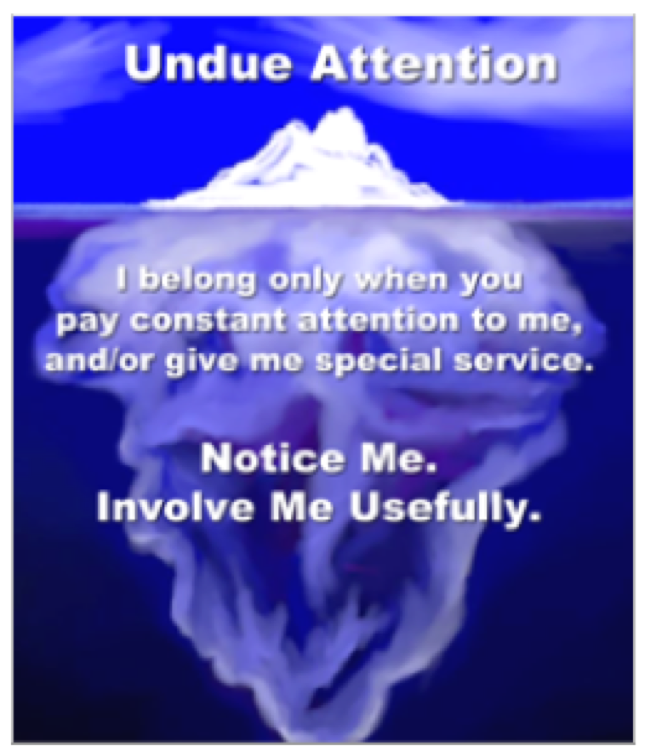

Undue Attention

When it is about undue attention, usually the adult feeling is irritation or annoyance. I often experienced this as a mother with young children. The moment I would get on the telephone, they would come and pull at my skirt or need my attention. It is that feeling of being interrupted and feeling like they need to be reminded again and again. If we use rewards and punishment and we chip away at that, or we even do our adult tendency of reminding, it is going to keep happening and that tip of the iceberg is going to get worse. This is because what is underneath the surface of the water is the mistaken belief that I belong when you pay constant attention to me and give me special service.

Figure 7 shows the child's coded message, which helps know which tool to use is, "Notice me, involve me usefully." What I have found as a parent and educator is when I have that feeling in a challenging moment of irritation or annoyance, I pretend the child is literally wearing a ball cap that says, "Notice me, involve me usefully." We find a job to do together, we connect, and we shift from that challenging behavior to building a life skill.

Figure 7. Undue attention, from www.positivediscipline.com.

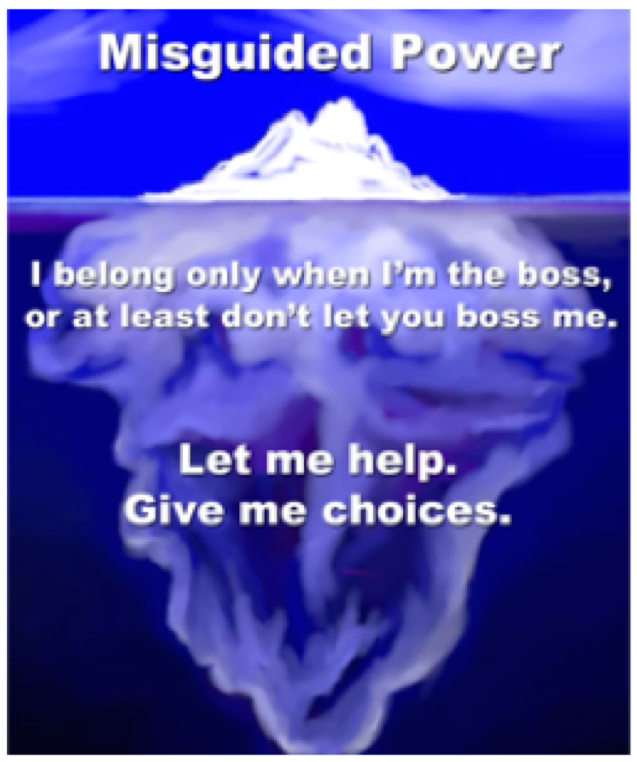

Misguided Power

The next goal is misguided power. Usually, when this is the purpose of the behavior the adults feel that sense of, "I have got to show him or her they cannot do this," or that you want to draw a line in the sand. Again, just chipping away at the tip of the iceberg is going to make it worse. If you do, you are going to develop a pattern of getting into a power struggle with that child because the child's mistaken belief is, "I belong only when I am the boss or at least do not let you boss me."

The coded message as seen in figure 8 is, "Let me help. Give me choices." When I feel that moment of challenge, I pretend the child has on the ball cap or the T-shirt that has the coded message on it. Some young children tend to need to have more power, so we want to give them personal, positive feelings of capability. It is helpful to give them more choices, within limits, because we are firm and kind at the same time. For example, "Would you like oatmeal or a granola bar? "Would you like to start with the blocks or do you want to go pick up the books?" Anytime we can provide choices and let them help, the more that tip of the iceberg will melt underneath the water's surface.

Figure 8. Misguided power, from www.positivediscipline.com.

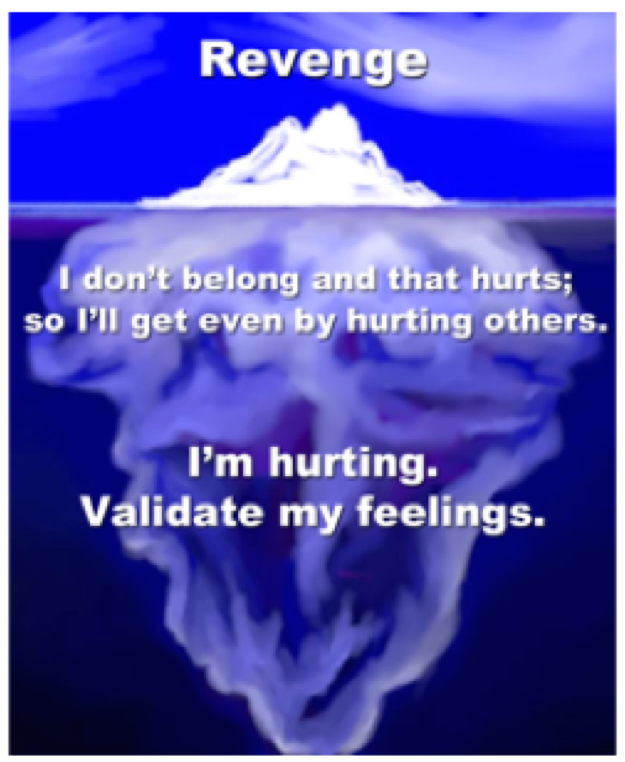

Revenge

The third goal of misbehavior is revenge. As seen in figure 9, the mistaken belief of revenge is, "I do not belong and that hurts, so I will get even by hurting others." The adult feeling is usually disbelief or hurt. The coded message is, "I am hurting. Validate my feelings." As an adult, when we feel hurt, our first instinct is often to give empathy. When the child is in a revenge cycle, or hurting, they are so fragile. They need their feelings validated, and again, they need connection before correction, which is the key fundamental of positive discipline. They need connection to fill that sense of belonging because when belonging goes up, stress goes down. They need empathy. We need to do some repair before we can move on to discipline for teaching.

Figure 9. Revenge, from www.positivediscipline.com.

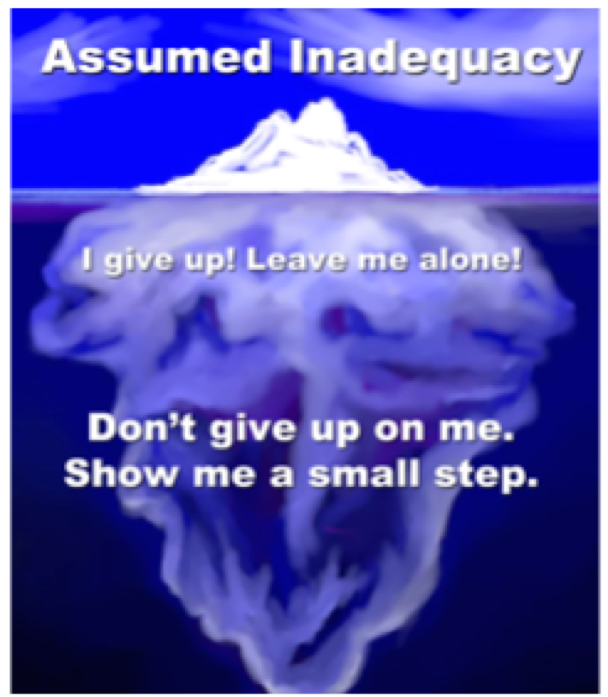

Assumed Inadequacy

The final goal of misbehavior is assumed inadequacy. In very young children, sometimes we see avoidance, whether it is the avoidance of going into the circle or of getting in line. The mistaken belief as seen in figure 10 is, "I give up! Leave me alone!"

This is very rare in an early childhood setting, but sometimes if young children have learning disabilities that are not yet diagnosed or speech issues that have not been addressed, they can become very discouraged and want to give up. The coded message on the cap is, "Do not give up on me. Show me small steps." Breaking things down, using encouragement, and focusing on the direction of growth moving forward will help these children.

Figure 10. Assumed inadequacy, from www.positivediscipline.com.

One of my favorite quotes is by Maya Angelou, who I was blessed to have at the University of Wake Forest when I was an undergraduate. She said, "I have learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel." This has been so important to me, especially when working with young children because they sense adult frustration and if you believe in them or have faith. Remembering the guiding principle that we want to build the relationship and keep that sense of connection in place is so important as we discipline and teach young children.

Class Meetings

The final, but most important tool in positive discipline, especially in schools and early childhood centers, is class meetings. As soon as students can sit up, I recommend getting in a circle as often as possible. If there are enough adults to be involved, you can even put really young children in your lap or in their high chairs in a circle to build that sense of community. There is so much research that focuses on having circle time that is reflective and not about direct instruction and builds that sense of community and belonging. The CDC points out that when there is a high sense of connection in a learning environment, students are more engaged, academic learning is improved, older students' school absentees decrease, and there are less bullying and fighting incidents.

Positive discipline class meetings are an opportunity for children to learn and practice many skills. These skills are the same as on the characteristics and life skills that we brainstormed at the beginning of our hour together. They include:

- Listening skills

- Brainstorming skills

- Problem-solving skills

- Mutual respect

- The value of cooling off before solving a problem (Problems are put on the class meeting agenda so a cooling off period takes place before focusing on solutions to the challenge.)

- Concern for others

- Cooperation

- Accountability in a safe environment (People don’t worry about admitting mistakes when they know they will be supported to find solutions instead of experiencing blame, shame, or pain.)

- How to choose solutions that are respectful to everyone concerned

- Social interest

- That mistakes are wonderful opportunities to learn

Positive discipline class meetings, which we advocate daily, help give an opportunity on a regular basis to help children connect. In the beginning, you might use puppets to start building language skills for young children to be able to give compliments and show appreciation. Prior to expressive language development, there may be modeling of these building blocks for class meetings. Being in a circle where everyone can see eye to eye helps to start building appreciation for one another, and as developmentally appropriate, being able to have children work together to solve their problems.

One thing that is different between positive discipline class meetings and morning meetings, or traditional circle time in early childhood, is they are not about direct instruction. They are about community-building, developing life skills for problem-solving, and figuring out problems together. Research from the CDC says the more children can work together and be in groups where over time, they develop the skills to build that sense of community and problem solve, the better the academic outcome is.

I have worked with teachers of children as young as two and a half to three years old to support them doing daily class meetings. What they find and what research has shown is in pre-K through elementary school, in both quantitative and qualitative studies, teachers actually have more time for academic learning and getting to all the activities such as playground and music and art. They also find that there is less disruption within their day and that they can transition easier. This is because, over time, children learn that if issues come up or there are conflicts to work out with peers, they have a controlled venue in their class meeting time to be able to solve those problems and learn once there has been a cooling-off time.

Having traditional circle time where you go over the calendar or provide direct instruction can be extremely valuable, but it might need to be a separate part of the day from your positive discipline class meeting time to avoid long periods of sitting. I encourage these times to be short and have as much interaction as possible to engage and draw forth from the students. The positive discipline class meeting time is a time where you come together, connect, and then focus on problem-solving.

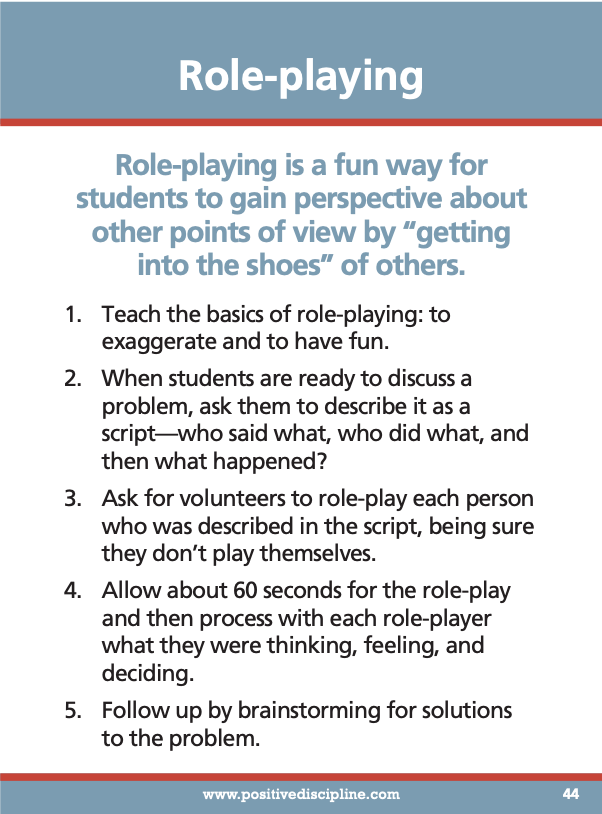

Role-Play

To do that, we use brainstorming solutions and role play. There are some creative ways to do this with young children. The idea is that when there is a problem we identify the problem, role-play what the problem is, then brainstorm solutions around the best ways to solve the problem. The problem may be pushing in line or lining up safely or how we are going to get to music class quickly, quietly, and safely in the hallway to respect other's learning time in school. When identifying the problem, the teacher may need to point out what she sees and assist the children in role-playing that problem so everyone understands what it is. As soon as is developmentally appropriate, get students to brainstorm solutions around the best ways to try to find a way that they can solve the problem. One of the great things about positive discipline class meetings is as early as possible, we are teaching, we are calming down, we are focusing on solutions, we are trying the solution, and if it does not work, we are going to go back and try again.

The best example I have ever seen of this was a preschool class that was having trouble on the playground dividing equally into soccer teams. The school had gotten a brand new area on the playground with soccer goals, but there was so much conflict about fair teams at recess they never got to play. Everybody was pushing and shoving and there were arguments. The agenda item in the class meeting was, "How do we pick fair teams?" One student suggested, "Let's count off one, two, one, two, and if there is somebody extra then they are the referee or we go find somebody else to join our game." They made guidelines together about fair play. This all occurred in mid-fall and because they decided and agreed together, for the entire rest of the school year, those four-year-olds managed going out, creating fair teams, and playing soccer.

There are very specific steps to do this, as seen in figure 11. You can learn more through the positive discipline website, positivediscipline.org. Through class meetings we are connecting, building that relationship, and then as problems come up, in a controlled venue, we role-play out the problem.

Figure 11. Role-playing, from www.positivediscipline.com.

Early on, this needs to be done by the teacher. There is a great strategy that Terese Bradshaw, a Montessori teacher and positive discipline trainer, developed to do this. She takes pictures of her students and puts them on small thread spools as seen in figure 12. I have used Popsicle sticks instead. She teaches role-play first by modeling what she sees with her co-teacher and then later using these people puppets to show how to line up or how to play fair or how to go down the slide. Then when it is developmentally appropriate, she shifts to having the students problem-solve together and role-play.

Figure 12. People puppets for class meeting role-play, developed by T. Bradshaw.

Many classroom teachers say that it might take too much extra time to hold class meetings or they might not be able to manage the group in a circle. I really encourage you to try it. While working in a school where there was a lot of direct instruction, students were in lines, and classrooms were big, teachers shared with me, on a personal note, that it seemed very overwhelming to get students in a circle. Doing this is a facilitative process instead of a direct instruction process.

Positive Discipline Association is a non-profit focused on teaching early childhood educators about these skills and how to use positive discipline in their classroom and focus on long-term results as well as train parent educators. In the book, Positive discipline tools for teachers: Effective classroom management for social, emotional, and academic success, the Adlerian theory behind each tool as well as preschool, middle school, and high school teacher class stories are shared, and what the research says about each tool is included.

Questions and Answers

About what age can you start doing role-play with young children?

I have helped support toddler teachers and late twos doing it when there are three adults in the classroom. Again, at that age, it is using puppetry and focusing more on modeling giving compliments. Shifting to role-play and brainstorming is around the age of three, and I have done it with class sizes as big as 20 students with at least one of the classroom teachers staying and helping me and learning as I model. In the beginning, you might use the other adult in the room to show what the scene looked like, and role-play that way. You can then follow up with the people puppets if you have the resources to do that, or using puppetry, then shifting to asking students if they would like to volunteer to come up to show what it looks like when something is happening so everyone sees the problem as it is happening before they try to brainstorm a solution.

Can you tell me more about the people puppets?

On the first day of school or sometime during the first week, most teachers take pictures of students up against a wall to use for various reasons. We made extra copies and laminated them so they would last. Then we cut them out and put them on a Popsicle stick. They are small, even though they look large in the picture. The teacher mentioned previously attached them to an empty spool, like from a spool of thread. I have seen teachers just use the face or just use puppets to teach role-playing. I think it personalizes it for the students. Some of the social-emotional learning research shows that integrated daily practice with real student problems is the most effective.

Resources

References

Baumrind, D. (1991). The Influence of Parenting Style on Adolescent Competence and Substance Use. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 11(1), 56–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431691111004

Dreikurs, R., Cassel, P., & Ferguson, E. D. (2004). Discipline without tears: How to reduce conflict and establish cooperation in the classroom. Mississauga, Ont.: J. Wiley & Sons.

Dreikurs, R. & Dinkmeyer, D.C. (2000). Encouraging children to learn. UK: Psychology Press.

Dreikurs, R., Grunwald, B. B., & Pepper, F. C. (1982). Maintaining sanity in the classroom: Classroom management techniques. New York: Harper & Row.

Dreikurs, R., & Soltz, V. (1964). Children: The challenge. New York: Hawthorn/Dutton.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Random House.

Nelson, J. & Gfroerer, K. (2017). Positive discipline tools for teachers: Effective classroom management for social, emotional, and academic success. New York: Harmony Books.

Nelsen, J., Lott, L., & Glenn, H. S. (2000). Positive discipline in the classroom: Developing mutual respect, cooperation, and responsibility in your classroom. Roseville, Calif: Prima Pub.

Citation

Gfroerer, K. (2020). Positive discipline tools for teachers: alternatives to rewards and punishment. continued.com - Early Childhood Education, Article 23700. Available at www.continued.com/early-childhood-education