Introduction

Today we're talking about screen time and the negative associations to child development. This seems like kind of a dark topic because we're thinking about what the research shows in terms of the associations that might not be positive for kids. We know that children are growing up with screen time happening at a younger and younger age. The average child in America now starts screen time at four months of age. Even though you're getting all of this information today about these negative associations, I want you to think about how you can share this information with parents.

I'm a big believer in building off of parent's strengths and building trust with families. We probably wouldn't want to go into a conversation with a parent whose child has a lot of screen time by sharing all the negative associations that the researchers are beginning to find. Keep that in mind and later I’ll share ways to have these conversations with parents in a way that doesn't make parents feel guilty or too worried, but in a way that supports them and their child's development.

Interaction and Play (Secondary to Background TV)

First, I want to talk about background television, which means that it's not something a child is sitting and actually watching. It can be any type of a show, whether it’s the news or something Mom and Dad are watching or a cartoon playing in the background. The child might be eating or doing some other primary activity and the TV is just playing, whether the child's actually looking at it or not.

Some researchers have seen that there are some negative associations to just having the television on in the background, especially for young children. A study in 2008 by Schmidt, Pempek, Kirkorian, Lund, & Anderson saw that when the TV is on in the background, one, two, and three-year-olds’ attention is shorter during play episodes. This means that instead of playing with an activity for three minutes, they're only playing for one minute. We learn this by comparing their attention when there is a TV on in the background to when it is off.

In 2009, Kirkorian et al. found that TV on in the background interrupts a child's ability to process verbal information. If a parent is talking to their child with the TV on in the background, then the parent will be more likely to have to repeat themselves multiple times compared to if there is no television on in the background. That's also a common sense thing because it's even true when adults have something on in the background and then maybe someone else says something, they have to repeat it multiple times.

Kirkorian et al. (2009) also found that parents themselves are also found to be less attentive with their child if the TV is on in the background. If there's no TV on in the background, these studies found that the parents took more initiative to make comments and to interact with their child and to show attention to their child versus having their attention deviated perhaps to the television in the background.

New Research Direction: Parents’ Own Screen Use and Child Development

For many years, researchers have been wanting to know specifically what the screen time impact is on children's outcomes. In recent years they’ve been looking more closely at what the parents' screen time impact is on their children. They want to know if a parent who is looking down at their device has any kind of an early impact on child development. There are a couple of studies that are pretty interesting. The first one by Yu and Smith (2016) looks specifically at one-year-olds. This wasn’t specifically just a parent using a screen. What they found is that when the parents sustained their attention on what the toddler was doing, then the toddler's attention was sustained longer. When the parents' attention was distracted, then the child's attention was also shorter to the activity. These researchers made some conclusions about modern-day times where parents are responding to devices or being distracted by their own technology or screens, or anything else. It doesn't even have to be screen-related. Parents who are less focused and attentive will also have children who during those tasks they measured were also less attentive.

Another really interesting study, especially for me as a speech pathologist, is related to word learning. Reed, Hirsh-Pasek, and Golinkoff (2017) tested these two-year-olds in a research booth with different toys and had parents try to teach their children new words. They would have the parent hold up an object and try to teach the child what it was called, but they would use a nonsense word. When you're doing research, you can't make the assumption that the child doesn't know what something is. For example, this is a coaster (holding up a coaster). The child might already know that, so they would call it something like a blick and they would try to teach that to the child. The children who learned the words were the ones whose parents were not interrupted. If the parents were interrupted by a phone call or a text on their phone or something such as that, the children did not learn the new words. The researchers specifically used phone calls on cellphones. This just goes to show that there are some interruptions that can affect language development for some children.

Interaction and Play

I want to talk about interaction and play and it isn't specific to screens, but it's specific to electronic toys. I talk about electronic toys because they have some good purposes for young children. They teach a lot of kids cause and effect, which is an important skill. For example, when you push a button and something lights up, or you push a button and music plays, that would be considered an electronic toy. There are so many different toys that toddlers play with like that. A lot of them move and sing and they do teach that child the cause and effect skill where if they do something, then something happens. That's an important skill for kids to learn especially because if later we teach them things like if I do this, then I get more, or if I say more, then someone understands me. Teaching cause and effect is a necessary skill, but something to think about in regards to electronic toys is that they have a lot of what we would consider to be formal features. They're drawing children's attention in based on those lights and noise and movement, and that's actually the same thing that television shows do.

For very young infants, their eye gaze is drawn to the screen based on the lights, the movement, the noise, and the background noise. That's what actually sustains young children's attention to a screen, not their ability to understand what's happening or the storyline, it's all of these formal features. So electronic toys are like the 3D version of a toddler's show. So, even though they serve that cause/effect purpose, we definitely like kids to move beyond just becoming fixated with these types of toys and play and graduate into more of the pretend play and imaginative play, such as using a box as a hat or a sled or different ways that they're playing with toys that are not electronic.

Sosa (2016) found that when very young toddlers (10 to 16-month-olds) played with electronic toys, children and parents were found to use fewer words and vocalizations compared to when they played with non-electronic toys. I think that would also be very similar to what we find with the 2D version of electronic toys or a screen or a tablet. We often see that kids are quieter when they're playing those types of devices compared to playing with things that require them to use their imagination.

Self-Regulation

According to Shonkoff and Phillips (2000), self-regulation is the ability to have control over yourself including bodily functions, manage your emotions, manage your behavior, and maintain focus and attention. It's a skill that develops, so children are not born with the ability to self-regulate. It usually starts with more of what we see as mutual regulation. This is where the caregiver helps the child to regulate from infancy by picking the baby up and rocking it, giving a bottle, or providing some kind of external regulator, whether it's the mother, a bottle, a pacifier, or something else. Gradually over time, children learn how to self-regulate on their own. They learn how to calm down. This could be when they learn how to take a blanket from their bed or something similar.

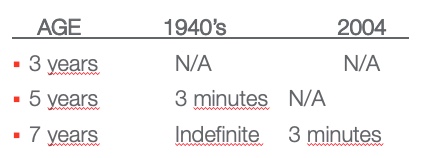

I've been traveling and doing these talks now for four years and I've been able to meet many different clinicians across the country. Many occupational therapists I speak with who work quite a bit on self-regulation tell me in general that we see this trend toward self-regulation skills declining in children. Take a look at the chart in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Self-regulation chart - standing still.

In 2013, Berova, Germeroth, and Leong looked at the simple skill of being able to stand still. They found that in the 1940s when three-year-olds were asked to stand still, they were unable to do it, five-year-olds could stand still for three minutes, and seven-year-olds could stand still indefinitely. But now, we repeat this study, already 15 years ago, and we found that three-year-olds still couldn't stand still when asked, but also five-year-olds couldn't as well, and seven-year-olds were only able to do so for three minutes. I find this research to be pretty interesting. Something else to be aware of is that when this first study took place in the 1940s and 50s, most cities in the United States were just beginning to receive television sets, so there wasn't a culture around TV yet. Even in the 1940s and 50s, there were very few programs for children, and if there were programs for children, they were watched and intended for younger children than what we see kids watching and what's being developed for young kids now. Figure 1 shows that through comparison studies there's some evidence to show a decline in children's ability to self-regulate.

There's some interesting research by Wartella, Rideout, Lauricella, and Connell (2013) looking a little bit more into self-regulation. Parents were surveyed and they found that parents admit to regularly giving or removing devices as a way to reward or punish their children's behavior. They call them "digital pacifiers." We see this all the time out and about. For example, if you are in a grocery store and a child is having a meltdown, you might see their parent hand them a cellphone, and then maybe that quickly calms them down. In one way, parents are reinforcing that negative behavior, but it's also giving that child an external regulator, which is the same thing as what a pacifier would do for a young child.

Wartella et al. (2013) also found that 71% of parents report that they don't feel these devices make parenting any easier. After talking to many parents about the situation, most parents that have older children or a big age gap between their kids will very often tell me, "It was so much easier with my older one when we didn't have an iPad." Parents who introduced an iPad when their child was really young often admit that they feel like their child almost has an addictive behavior to it. For example, their meltdowns are so intense when they try to remove it and the parent will say, "I wish I never introduced it." Once you have introduced the iPad or similar device, it's very hard to take it away. We do see some parents trying to manage or help their children regulate their behavior with these types of devices.

Another study by Radesky, Silverstein, Zuckerman, and Christakis (2014) found that poor self-regulation in infancy was associated with more screen time by age two. We have to again think about these studies and how they're conducted, so you can't really rule out what happened first. Was the child having poor regulation issues and therefore the parents coped by providing an external regulator, such as YouTube videos on a cellphone, and then that developed this habit? The researchers are also saying we also don't know if perhaps the child had a lot of screen time or was exposed to apps and videos and these kinds of things on devices early on and therefore, their regulation was affected.

Let's talk about the terrific twos. As we know, children are supposed to go through this phase of being difficult around two years of age, which a lot of parents will say is really from 18 months to three years of age. This is a big window for when we see children experimenting with their boundaries and testing and trying out behaviors and seeing what works. As a speech pathologist, I work with a lot of children who are developmentally delayed, and sometimes we don't see the terrible twos emerge until the child's four, but developmentally, they've now hit age two. I talk to parents about how the terrific twos are normal and we want kids to go through this process and we want them to go through it when it's developmentally appropriate.

When we see kids having meltdowns or extreme behaviors or difficulties, there's a spectrum of that. A certain range of that spectrum is considered normal and kids need to be able to learn how to get upset and calm back down, and get upset and calm back down, and that's how they're developing their self-regulation abilities. Those are opportunities for parents to work through those with their children, to explain, to talk to children about those things, and for kids to learn, "When I get upset, I can self-regulate, and I can calm back down."

I have a lot of conversations with parents of two-year-olds who are afraid to bring their kids to the store or don't want to leave the house with them because they might have a tantrum. I tell them it's okay, it's normal, you're going to go through wanting something and being told no and that's okay, that's an opportunity, and we can work through this. However, I find that a lot of parents feel really insecure about this. They'll say, "But the other two-year-olds around me in the store aren't behaving that way." When I probe a little bit deeper, it's often because the other child's perhaps on a device, or going through the whole grocery store trip watching YouTube videos. They're content with getting that feedback loop of having attention to something that is a preferred item, so there's no reason for them to have a meltdown over something else.

In some ways, I get very concerned that these devices are again being used as digital pacifiers and we're not giving kids the opportunity to go through this normal phase of development, of learning to deal with frustration, to cope, and to manage those feelings. I share this with you and with all the parents I work with about how it's really a normal part of development. We want to encourage it and we don't want to prevent it from happening because this is such an important opportunity for kids to learn how to self-regulate.

Strategies for Teaching/Improving Self-Regulation and Mutual-Regulation (Adults’ Goals)

- Creating manageable challenges

- Increasing wait-time

- Visual schedules during routines (knowing what to expect)

- Visual behavior charts

- Label emotions (teach what activities affect feelings)

- Teach/model relaxation strategies (e.g. deep breathing)

- Teach/model arousal strategies (e.g. drinking water, physical activity)

- Waiting/listening games: Duck, Duck Goose, Hide & Seek, Musical Chairs, Red Light/Green Light, Simon Says…

- Model appropriate behavior, coping skills, managing feelings

- Fostering independence

- Responsiveness (empathy, patience, encouragement), on the child’s level

- Repetition

- Give alternatives & provide choices

- Allow practices (adult controls the scenario in order to teach)

- Environmental arrangement (structuring for success – manageable challenges)

- Adjust the language level

- Routine schedules/predictability

I've included a pretty long list here of some basic self-regulation strategies. These are adult goals of things that adults can do to help children. Some of them are really simple, common sense things to do. I included a whole bunch of them because different strategies are going to work and be meaningful for different children and different families. For example, what works for one child is just hearing a parent talk out loud for them. An example of this would be hearing them say something like, "I see that you're frustrated right now. I know this is difficult. We still need to stick to what we're going to do first, and then later, we can talk about next." That can be really calming for one child while another child needs really clear choices. For example, "It's this or this." Another example is understanding concrete rules with visual supports. I will say that kids need repeated opportunities to practice these skills. Especially with very young children, you can't just teach it or expose them to deep breathing one time, you've got to practice it often.

One of my favorite strategies that someone shared with me at a conference is a deep breathing technique where you show a child a picture of a flower and a picture of a candle, and you tell them to sniff the flower then blow out the candle. It's such a great visual for really young children. Also, these waiting games are good for children ages two-year-old and up. However, some two-year-olds might not be ready for the games. During games such as musical chairs, you're dealing with some disappointment when you don't get that chair, but then it's an opportunity as well to get excited for your friends, or to talk through it, or to play again, and this time, make it further in the game. The same for games like hide and seek, red light, green light, and Simon Says. These are all games that challenge our working memory. We have to listen, pay attention, wait, process, and respond appropriately. Self-regulation is one of our cognitive skills along with working memory. It kind of works together in that part of the brain, and that's why these games exist. I'm sure many of us played these games as kids. I just want to give a plug for those things and say that we're not replacing these types of activities for just screen time.

I'd like to speak about older kids for a moment. I find a lot of kids who have never heard of things like Chinese jump rope or other stuff like that that we did as kids because now they're talking about Pokemon Go and virtual reality apps. I think in general, there is a place for both. That's oftentimes the best way to present it to parents as not like an all or nothing, but as a balance and how to navigate that balance.

Sensory Processing

I want to talk about sensory processing because it comes up so often when therapists and parents ask questions such as, "Is the screen time affecting their ability to process information? Is it impacting their sensory processing disorder?" In general, we know we all have different sensory issues. They only become a problem if they disrupt our everyday life. Right now to date, there are no studies that specifically link screen time to sensory processing disorder or sensory processing disorder to increases in screen time for children. That's because it's really hard to determine the causative factors. We can't say this caused this because there are always going to be so many other things at play such as caregiver's education levels, sibling exposure, socioeconomic status, and many other things that you have to account for. All of these things make it really hard to say this caused this. Anecdotally, I hear a lot of this. A pediatric occupational therapist shared this with me and she gave me permission to reshare it with other audiences anonymously.

Speaking of her own daughter, she says,

Too much screen time for my daughter is a huge trigger for meltdowns with my 5-year-old who has sensory processing disorder and anxiety. We try to keep it (screen-time) under an hour per day and no commercials. She is SO drawn to it (technology) as are many kids with sensory processing disorder. They love the visual stimulation but often have a hard time modulating when they've had enough. Too much (screen-time) leads my daughter to irritability, lethargy and then hyperactivity (lots of proprioceptive seeking behavior). There is a lot of research about the effects of early media exposure in children. The American Academy of Pediatrics even recommends NO screen time in kids under 18 months and less than an hour daily for kids 4 and under. I would think the same rule would apply and even be more important for kids with sensory processing disorder because they just can't process and modulate the input well.

- Pediatric OT

When you ask other parents and therapists, they all report observing the same thing. Again, we don't have the research to back this up yet. I can just say for my own self having two children that they both seem to process sensory input very differently and screen time as well. I noticed that after my son watches a show, he gets really hyper as if he's been sitting too long and is now kind of bouncing off the walls. After my daughter watches something, she gets almost angry that it's over and she lets it out. A lot of parents say that they feel like after some kind of screen time input they sometimes notice behavioral changes in their kids, but we don't have any research drawing conclusions about this yet.

Behavior

There's been a little bit of research about TV viewing and associations to behavior. In Montreal, Pagani, Fitzpatrick, and Barnett (2013) conducted a large study with about 1,000 children who were two years, nine months of age. Then they tracked how much screen time they had all the way through 13 years of age. They found that the children who had the most screen time, and by the most, I mean they averaged at least an hour more per day at two years, nine months than the other kids, also had the most significant issues regarding peer victimization. Let me explain that a little bit better. At two years, nine months, on average, those toddlers had 90 minutes of screen time daily. There was another group who had an hour more than that a day, so two and a half hours a day. That same group of children who had the most screen time was followed and they were looked at in fifth grade, and then in sixth grade, and then at age 13. When those children reached kindergarten, they asked the teachers which kids in your class are the kids who don't seem to have real friendships or who might get picked on a little bit. The teachers reported the kids who had the most screen time during their toddler years. In sixth grade, they asked children themselves to self-identify which of their peers were the ones that struggled with friendships and might be bullied. The peers self-reported the kids who had the most screen time during toddlerhood. in 2016, Pagani, Levesque-Seck, and Fitzpatrick then asked the children, now age 13 years, to rate themselves on their peer friendships and being bullied or bullying others. The children who had self-identified peer victimization was the same group of kids who had the highest rates of screen time in toddlerhood. This is very interesting research and I believe they might still be following these kids to do another follow-up study. Again, it's hard to make those conclusions, but this is one of the more well-conducted studies that was a little bit larger sample size of about 1,000 children.

Technoference

Still thinking about behavior, there's something called technoference. This is a new-ish researcher term that has to do with the association between parents who are being interfered with by their device (stopping to look at their device) and children's behavioral problems. McDaniel and Radesky (2017) found that parents who stopped to look at their devices reported that their children had more behavioral problems, such as hyperactivity, whining, and tantrums. They based it on their research on two-parent households which was done with 170 families with the average age of the children being three years old. Those were parents' self-reports of their own screen use and then their children's behavior.

There are some other interesting studies looking at this too. Some of them are a little bit more dated, but when cellphones weren't as popular, they would look at children at a fast-food restaurant and they would find that the kids whose behavior was the most squirrelly or the naggiest to their parents were the ones whose parents were on their cellphones. I don't know if that study has been repeated or not, but it's a little bit older when it was less common to see parents on their cellphones in restaurants.

Motor Development

There's not been a lot of research looking at motor development outcomes, but if you talk to any physical therapist or occupational therapist, a lot of them do agree that we see a greater frequency of kids with motor development delays. I want to go back to the study that I mentioned before with the toddlers in Montreal who were two years, nine months because they also looked at the motor skills of those children. What Pagani, Fitzpatrick, and Barnett (2013) found was that their TV viewing at 29 months of age was associated with poor gross motor skills by age six. Then they continued to follow those kids, again, to sixth grade, and then to age 13, and they did not see long-term repercussions, meaning those kids had caught up to their peers in terms of gross motor development. Those same researchers also looked at fine motor skills, but they did not see any association between increased screen time and fine motor development delays.

There's some new research that's happening right now looking at fine motor development in general, such as children's screen skills, meaning that the time that a child can scroll on a device seems to go hand-in-hand around the same age that a child can stack blocks. The researchers are not finding any indication that being able to swipe or scroll is having a positive impact or a negative impact on fine motor development. We just don't have strong research indicating if fine motor development is being impacted negatively or positively by early device use.

Fact Check: Does Screen-Time Cause Delayed Language Development?

Let's do a quick fact check. The question that comes up to me often as a speech pathologist is "Does screen time in fact cause children to have delayed language development?" The truth is, there are mixed results of some studies. Yes, they have seen a negative association between early screen exposure in infancy and later language development. However, other studies have found no association between screen time in infancy and later language development.

- Several studies found a negative association between media exposure in infancy to later language development (Duch et al., 2013; Pagani et al., 2013; Tomopoulos et al., 2010; Chonchaiya & Pruksananonda, 2008; Zimmerman, Christakis, & Meltzoff, 2007; Linebarger & Walker, 2005).

- Other studies found no association between screen time in infancy and later language development (Ruangdaraganon et al., 2009; Linebarger & Walker, 2005; Schmidt, Rich, Rifas-Shiman, Oken, & Taveras, 2009).

The truth is that we don't have enough research yet to have done like a big well-done meta-analysis on this topic. I'm sure we'll see something like probably in the near future I would imagine, but right now, it seems pretty mixed. I take this and think, well, we could err on the side of caution ideally and try to limit some screen time if possible, but in general, I don't think that we have enough information to say yes, this is actually a causative factor for a child with a language delay.

Attention Questions

There's been a very small amount of research looking at attention. Christakis, Zimmerman, DiGiuseppe, and McCarty (2004) conducted a study in 2004. They thought screen time was causing ADHD. This study went a little bit viral and people caught wind of it, and they started making those big associations, but there were a lot of problems with the study. The intentions were good, however, the study had problems with the reliability and they were using a parent report of children's attention and these were not kids who had an actual diagnosis of ADHD. Then another group of researchers said, "Okay, let's replicate the study." When they replicated the study, they did not find the same results. In general, what we know is that there's not any research right now that's clearly showing a negative association between early screen exposure or excessive screen exposure, and later outcomes with ADHD, we just don't have those studies.

I share about the things we don't know yet because I feel a big responsibility to look closely at the research to know what's well done because screen time is such a huge, popular hot topic, and there's so much information out there. You could find anything you wanted in blogs or in social media groups. If you wanted to find out if screen time cures ADHD, I think you could find it online and if you wanted to find out if screen time causes ADHD, you could find it online. I'm really trying to bring you what we actually know for sure today, and there's a lot of stuff we don't know, as you can see.

Health

Weight

One of the areas that we do know quite a bit about is screen time exposure and weight. There have been a number of studies that have shown that young children who watch two or more hours of TV daily tend to consume more high fat and high-calorie foods compared to children who have less screen time. Manios, Kondaki, Kourlaba, Grammatikaki, Birbilis, and Joannou (2009) conclude this is because if they're watching a lot of TV and having a lot of screen time, they tend to be snacking and a lot of snack foods are high in calories and high carb foods.

Dennison, Erb, and Jenkins (2002) found that children who had televisions in their bedrooms had a higher likelihood of being overweight. We also have concerns about children's weight in general as we see childhood moving more and more indoors. A lot of these things again are hard to tease out, but we do see that obesity rates are higher for children in low-income families. In general, low-income families often tend to have more low-cost foods, which are often higher in calories. For example, a lot of snack foods are more affordable than fresh fruits and vegetables, so it's not that we can necessarily make a strong conclusion that this is because of the screen because there are all these other factors to consider.

Let's think about how we share this information with parents. If we know a parent is not going to necessarily decrease their child's screen time, we can always make suggestions for a change in screen time. I was working with a family and the mom was home all day with the kids. She didn't drive, didn't have a safe area for her kids to play outside, and she felt guilty that she was letting her kids watch a lot of TV. She said, "We're home together all day. We can go for a walk, but it's not necessarily the safest area." Transportation was just difficult in general. She already felt kind of bad about this amount of screen time, so one of the things that we did was just showed her how she can access the other types of content to make it more physical play for her kids. She was able to do yoga videos on YouTube with her kids and it became more of a fun activity that they were doing together as a family.

Some other examples include Go Noodle, kid's yoga videos, Pokemon Go. These are apps that combine screen with virtual reality. Geocaching is another one for a little bit older kids where you can go outside and actually go looking for something. There's kind of a number of different things now. It's just another way of providing support to a family instead of just pointing the finger and telling them they're doing something wrong.

Sleep

Sleep is another area that's being looked at by the researchers. Garrison & Christakis (2012) found that children with a television in their bedroom were more likely to have sleep problems. This is not specific to very young children though. This is just children across a broader age group. Kabali et al (2015) found that 28% of low-income mothers reportedly used a mobile device to put their young children or infants to sleep, and some of the parents reported they would just basically hand the child the phone and hoped the child would be asleep before the phone died. According to Calamaro, Mason, and Ratcliffe (2009), we do know there's some concern that the blue light from the phone could be affecting melatonin release, which would then affect their sleep cycle, but there's very limited research on this, especially specifically for young children at this point.

Vision

I find this to be very interesting because I notice more and more of my friends and myself all tend to have vision problems at a younger and younger age. Nearsightedness (myopia) is on the rise for all ages. We've heard for a long time that the blue light could be affecting our eyes, but this study that just came out in 2018 was the first one that really showed there's something happening. Ratnayake, Payton, Lakmal, and Karunarathne (2018) found that blue light from screens may increase the rate of macular degeneration by “altering cell fate.” I'm sure there are going to be more studies coming out on that.

According to Sherwin et al. (2012), one really easy strategy to decrease the risk and progression of nearsightedness in children and adolescents is just to spend more time outside. We say that when we're outside, we tend to be looking further away. So if you're inside, you're often looking at things closer up. Just by looking further away promotes good vision, and also, you're also outside getting your vitamin D from the sun. Yazar et al. (2014) found that young adults with vitamin D deficiency were significantly more likely to be nearsighted.

Injuries

I have only seen one study that has looked at injuries since the emergence of smartphones. In this study, Palsson (2014) analyzed kids' visits to emergency rooms across the country. They have found that since the emergence of smartphones, young children up to five years of age have had more ER visits than they did previously. This didn't affect children five years and older and the researchers hypothesized that that's because when you're older than five, you don't need as much adult supervision to be safe. They felt that the increase was related to parents being more distracted by their cellphones, and so there was a rise in injuries for young children. This was only one study, so keep that in mind.

Mental Health

There is some new research that's been coming out and being looked at and it's related to mental health. Along with the University of Georgia, San Diego State University is currently looking at the mental health of very young children. They are starting to find some results that higher rates of anxiety in two-year-olds are linked to screen time. Bank et al. (2012) found that children whose moms are depressed watch twice as much TV. Mothers of children with autism are noted to have the highest rates of depression compared to other moms. Kids with autism also have a lot of screen time, more screen time we know than typically developing children. Pempek and McDaniel (2016) found that toddlers 12 to 48 months of age have increased tablet use when there tend to be relationship troubles between their parents.

These are just some interesting things to think about. There's a lot more research coming out on this related to older teenagers and into adults and how our own screen time and social media use is impacting mental health in general.

Brain Development

There's also some new research coming out on brain development. Here are a couple of quotes I'd like to share with you. Dr. Sarah Lytle is at I-LABS in Seattle and she quotes, "We really have not yet studied the effects of screen media on children's brain development. We are starting to get some technology that will allow us to ask these questions" (Arthur M. Sackler Colloquia, 2015).

James Steyer, who's the founder and CEO of Common Sense Media says, "We are conducting the biggest experiment on our children's lives, in any of our lifetimes, with virtually no research" (Rehm 2015). He's basically saying we're giving these little tiny infants and toddlers devices and we don't really know the outcomes of that.

There is some new research underway currently. Researchers were given $300 million to follow 11,000 children over the next 10 years to actually look at their brains and track what's actually happening in their brains when they look at a screen at different ages and see if it changes the trajectory of how our brains develop. We won't have that research published for many years, but at least we're beginning to look at this type of work now, and I'm sure we'll have some leading answers in the near future.

Fact Check: Can Too Much Screen Time Cause Autism?

Another question that I've been asked often is, "Do we think that too much screen time can cause autism?" I do quite a number of different talks related to autism and it's the area that I probably have the most experience with. I would say beyond a reasonable doubt, the answer to this is no. Sometimes parents will have guilt associated with screen time, or if they did something to cause their child's autism, and more and more, we're finding out that autism, whether we catch it early or not, it's there. Some researchers would say it's there, even before birth. I'm not those researchers, so I'm just sharing what I've heard said and what I'm starting to read from newer studies, especially since 2017. We're doing more brain scans and eye-tracking studies and we're getting really good at diagnosing autism at a much younger age. What I do think can happen is that if you have a child who grows up in an environment where they're not interacting with others regularly, they're not exposed to a lot of different social opportunities, or their caregivers may or may not be available, they may not have those basic foundational things in place. Instead, they might be spending a lot of time either on a device or in front of a TV or that background TV is going much of the time. Then we might see some kids who look like they have poor social skills or things that kids with autism also tend to look like.

I once worked with a family like this. There was a two-year-old whose mother had passed away and he lived with an elderly grandmother who just didn't have the means or the ability to get on the floor and play with him and meet his needs the way that maybe his mother would have been able to. He had a lot of screen time, and I think the grandmother genuinely felt that he was learning from this and she would try to have him watch educational shows. When I started working with him he was nonverbal, he had very few play skills, and very few opportunities to interact in a playful way with anyone. When you would give him something, he would spin it, or just kind of explore it, and he was very far behind developmentally. He looked like a child that had a lot of red flags for autism, but once we got him out into a healthy environment in a preschool program and Grandma got some support, it was like all the lights turned on for this kid. He had so many skills. He just needed the opportunity to be exposed and have different experiences and social experiences.

Donald Rumsfeld said, "There are known knowns; There are things we know we know." This is about screen time in general. There are certain things we kind of know. We sort of know that the blue light's not good for our eyes and for sleep. He also said, "We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know." We don't know about relationships between screen time and sensory processing disorder and ADHD. Last, Donald Rumsfeld said, "But there are also unknown unknowns - the ones we don't know we don't know." I always loved this quote.

So that's to say, we're doing all this research and looking at all of this stuff, but there's probably a lot of stuff we don't even know to be looking for yet, and we might not know for a number of years. We just need to be mindful. I share that with parents in the sense of, it can't hurt to err on the side of caution.

Assessing sources/information for trustworthiness and reliability

One of the challenges for conducting screen time research is that screen time cannot ethically be randomly assigned. If it could be, we'd have stronger studies, but we can't ethically say group A is going to get no screen time and group B is going to get six hours per day, that would be unethical. Also, we can't say things like group A is only going to watch educational content and group B is only going to watch violent content. If we could do that, we would be able to prove more about causation, but we can't do that ethically. It's really challenging to control for all these other factors such as parental educational level, socioeconomic status, family support, gender, culture, mental health, age, and so on. Because of that, we have to be aware that it's really difficult to conduct these screen time studies and it's really hard to control for all these different factors and to make really strong conclusions.

That's why when I bring you this information today I say think about it. You have more information now, but think about how you're going to use it. We're not going to use it in a way to scare parents. We still need to find a way to use it to support parents with what they're doing with their children. You should always consider your sources. Are you sharing a blog with a parent? Are you sharing something from a news outlet that's reliable? Are you sharing research that you're helping parents to understand? Try to use resources that are most valuable to parents and strong resources.

Also, if you have additional questions, you can always email me (email address in handout). In addition, I run a Facebook group called Media Mentorship for zero to 36-month-olds where I post about new and different research that's coming out and parent-friendly resources. It's also a place where parents and practitioners can ask questions. It's specific for young children, but sometimes, someone will share something about an older child too. It's also a place where you can go to find more reliable information.

Questions and Answers

Parents are going to be very reluctant to change their behavior at home, and not necessarily want to give up the iPad or the phone as a babysitter. What are some options instead of cellphones or iPads when they're out in stores, something to keep them quiet while they're shopping? Or if they're traveling in the car, instead of having the DVD player on for hours on end during a trip, what are some other options that teachers may use on their own children, or be able to share with parents?

I actually was having this conversation with a parent this morning and we were talking about the challenge because they feel like they've already sometimes fallen in these bad habits. A lot of parents talk about this during mealtimes especially. They often say, "I can only get them to eat if the iPad is right there and they're watching something." I think starting with, "We're just going to remove it," or "You're going to do this instead," doesn't always work.

It depends on the family, but definitely I feel like for a lot of kids, just weaning off of screens can be a big step. For example with the mealtimes, we'll talk about moving the iPad away in small steps. For example, right now, the iPad is right here, what if we put it here? We're backing something up and we're gradually lowering the volume. The next time, we're doing this, and the next time, we're pushing it further away, and then eventually, we get to pause, and eventually, we get to mute, and eventually, it's off, it just has to be within sight.

For some kids, it's going to have to be a weaning off process, or you might say, "You can have it in the car after, but first, you're going to look at these books that I brought," or "First we're going to do this and then we're going to watch that" or something like that. The same kind of concept can be used in the grocery store. For example, you might say, "Okay, you can only watch it in the fruit section and then when we get to this area we're going to turn it off." It needs to be something that's manageable for the parents.

Another thing to remember is that children, especially very young kids, love novelty. I encourage a lot of parents to make a bag by going around their house and filling the bag with different things that are just random odds and ends. This might be a rock or a paper clip, but make sure they are things that are safe and not choking hazards if the child might put something in their mouth. When you go somewhere, you give the child the bag, or half the bag, or a few things at a time. It's amazing how at that age, anything can be a toy. This is also easy to do as a teacher because you go through your own house and you find all kinds of things as you're putting stuff away, such as a random block, or a feather, or some other small item. You can make these little bags and then they can become little travel kits. It's so easy for parents to do and they don't feel like they have to buy anything. I just remember with my own kids when changing diapers became difficult, I would have to just hand them some random object. Then once I could do that, they were distracted enough. Now I see a lot of parents who don't do it with an object, they do it with the phone. Sometimes parents need that little idea to try something different.

What if you've got a child who is older? For example, if you've got a child that's four or five or six and they've been using the phone or screen for so long, would it just take that same process, but maybe take a little bit longer to go through that process of weaning off of it? The damage isn't done at that point and it's not too late to change, correct?

Sometimes at that point, parents are more motivated because they're starting to see it as the problem. I find that with the really little ones, a lot of times, I'm trying to help them prevent something, but for older kids, I feel like sometimes parents are like, "Okay, this actually feels like an addiction." The parents have a little bit more motivation and they're just looking for support and ideas. Then sometimes as I'm talking to them I find that it's not so much about the strategies as it is about parent support and education. We'll have conversations about self-regulation and those terrific twos and a lot of parents will say they never went through that. They never had to because they either gave them what they wanted or handed them the phone or maybe they did this or this happened instead. It's not about a blame game, it's just about giving them the opportunity to go through that phase of development now. Let them know that this is a way that you can support your child now, by letting them experience some disappointment and being there for them and explaining to them. It's a lot more about parent education when it comes to some older children.