Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Supporting Gender Diversity in Early Childhood, presented by Julie Nicholson, PhD and Nathanael Flynn, MA.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Define the gender binary and identify its limitations.

- Describe at least one reason why it is important to talk about gender diversity in the early childhood years.

- Identify at least one strategy they can use to create gender-inclusive early learning settings for children and families.

What is Gender?

Nathanael Flynn:

We wanted to start by bringing up the idea of what is gender? So often it's a responsive part of who we are as opposed to a reflected-upon part of who we are. When we think about gender, we often think about the people we see on the street and who we guess that they are. We talk about that as gender attribution. We look out and it often helps us navigate, sometimes in really unconscious ways. One small example of that is whether you step aside to let someone through. There are lots of things like that in our world that we do instinctively and without reflection.

Gender is also really personal. It's part of our identity and part of who we are. It is often self-defined and internal, but also it's a part of how we express ourselves. Gender expression is how we generally put ourselves out in the world and includes all of the little things and big things that make you feel like yourself. That can happen in lots of different ways, but for this course, we're zeroing in on how you express your gender identity or how you want the world to see you in a particular moment. It could be a professional moment or a personal moment where you want to feel relaxed and comfortable. Maybe it's the makeup you feel like you need to put on or the makeup you feel like you should never wear outside the house.

There's also a cultural aspect of gender. We're all navigating gender norms, including ideas of what people are going to expect or think will happen when we go out into the world or when we know we are not going to meet people's expectations. Gender can feel so natural and instinctive to our day-to-day life. In reality, these norms and ideas of what gender is and what it should be have changed. Gender norms may feel natural but they are specific to their time, place, and culture.

Take a look at the child in Figure 1 who is dressed up for a portrait. Who do you think this child might be?

Figure 1. Child dressed up for a portrait.

The child in figure 1 is a future president. It's Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) and he's dressed in typical boy's clothes of the time. At that point in time in his culture and his space in the US, all kids wore dresses under a certain age. It made it easier to take children to the bathroom before there were zippers and buttons. Another example is how colors have changed. Oftentimes in my world, pink is for girls and blue is for boys, but if you go back 100 years and look at children's pictures and read the literature of the time, people are advocating about how red and pink are strong colors meant for boys and too intense for girls. Girls need soft blue tones. These things shift and change. These are just examples of US stories, but there are stories all around the world about what things mean. We want to encourage you to be aware and thoughtful about the things that you bring back into the lives of the children in your life.

We'd like to encourage you to take a trip down memory lane. You might want to reflect and jot things down or you might want to move around as you remember them. Take a few minutes to think about the following questions.

- When do you remember first learning about gender?

- Did you notice any rules that you were expected to follow?

- Where or who did these messages come from?

- How did it feel to either follow those rules or break them?

- Think about a story from your childhood that features gender.

Think about what these things mean to you. When I think back about gender, I was a child who was really aware of what the rules might be, when I might break them, and how I could safely meander those rules in order to build some space for who I am. You might've had a different experience.

Messages We Received about Gender Growing Up

Julie Nicholson:

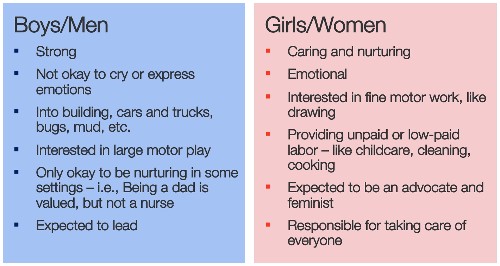

Figure 2 shows a visual representation of what we are going to be talking about as the gender binary. This is the dominant way of understanding gender in not only our US context but in many countries around the world. As Nathanael said, it is by no means the only way of understanding gender, but we want to start here because it's what most of us grew up with, it's what most of us are familiar with, and we want to make it visible because we're going to talk about it and some of the limitations.

Figure 2. Common messages received about gender.

In the gender binary, there are two boxes that people can fit in. You are basically assigned to that box based on a quick assessment at birth of the physical characteristics of your genitalia. You're either assigned to the boys' side or the girls' side, but a lot of things go along with which box you were assigned to. There are messages and norms about how you should dress, the kinds of interests you should have, as you grow up the kinds of jobs you should have, your romantic partners, and other norms, constraints, and expectations. Let's look at some of these.

We've asked people, "What are the messages that boys receive from the earliest ages about what it means to be a boy and what it means to be a man?" Some of the responses are in the blue box on the left in figure 2. These are things that people in our audiences all across the US have shared with us. Boys are supposed to be strong and it's not okay to cry or express emotions. They're into building, cars, trucks, bugs, and mud, and they're interested in large motor play like active play. Many people say that it's only okay to be nurturing in some settings. Being a dad is valued, but not being a dad who's too close and physical, and definitely not somebody in a caring profession, like an early educator or a nurse. Those are messages that would not fit in that box. You're expected to be strong, assertive, lead, have all the answers, be out front, and be comfortable with power.

In contrast to that, the right side of figure 2 in the pink box lists messages girls receive from the earliest age. Because of the box that they're assigned to, girls are supposed to be naturally caring, nurturing, and emotional. They're allowed to cry. They should be more interested in fine motor work, like drawing, sewing, and arts and crafts. They should naturally be called to do unpaid or low-paid labor, like childcare, cleaning, cooking, and teaching. They are expected to be an advocate, and in some circles, a feminist. They should be responsible for caring for others, and in many cases, invisiblizing the care to themselves.

Some of you might be thinking, "This makes sense to me. These messages are messages I've grown up with." Thinking about the gender binary, do you see how there are these boxes and no flow between the two? There's no flexibility. Children, youth, and adults who describe themselves as gender-expansive, non-binary, or transgender definitely don't fit into this gender binary. These are colleagues, friends, and children of ours who don't see themselves. It's not welcoming. It doesn't reflect them, but even if you do see yourself here, we believe and we ask you to think about the fact that there's no flexibility. We believe that there are probably times all throughout your life that you didn't neatly fit or you didn't neatly identify with some of the messages that you were forced to identify with being in your box. We are here to say that the gender binary is limiting for all people, including children and adults.

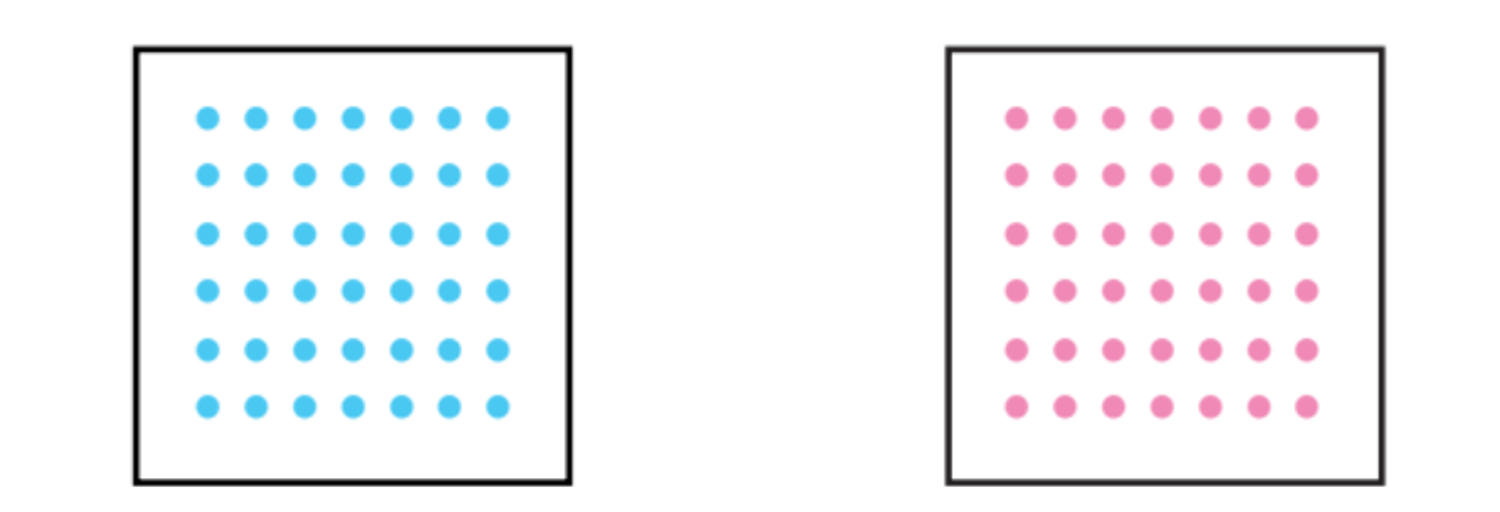

Figure 3. Stereotypes and social boxes.

Look at figure 3 and think about the expectations of the gender box that you're in and the way it has limited you. Think back and imagine a time when you were told you couldn't do something or shouldn't do something because that's not the way that girls should behave or women should behave or boys should behave or men should behave. There are stereotypes and limitations that harm and hold all of us back because they are so rigid and inflexible and don't account for what we know is true on all of this Earth, in all of humanity, and that is the normalcy of variation. Human variation and human diversity are the norms and how we all are. This doesn't account for that. We are here to help you think about other ways that we can consider gender, other ways that are more welcoming, more inclusive, more equitable and support all children and all adults' gender health.

Importance of Talking about Gender and Gender Diversity in Early Childhood

Nathanael Flynn:

As we're thinking about this, we also want to ask, "Why is it important to start talking about gender and gender diversity in early childhood?" People often ask, "When is too soon?" People are worried that things will get too big and too intense too quickly. I think sometimes they're also worried about not knowing what to say. The reality is we're always talking with children about gender, whether that's what color your room is going to be and what clothes you're allowed to wear. Think about how much our choices can impact children's mobility and access, from a baby in a dress who can't crawl without falling on their face because the skirt gets caught under their knees to whether or not they're encouraged to go play in the mud, with the trucks, with the balls, or with the dolls. All of these experiences offer us help in understanding ourselves. This isn't an idea of making children into something. This is an idea of being thoughtful about who the child is, what they can access, and what choices we're making in terms of how we present and share the worlds that they live in. One of the things we do see is in research, which can be limited based on what we can see from children. It's often limited to expression so things get benchmarked a little later to when children can talk about things, particularly in those early years when they've got five or six words to begin with, which can be so hard to know. Figure 4 shows some of these milestones related to gender and gender identity.

| Age | Milestones |

| 1 year | Begin to categorize individuals by gender |

| 18 months | Begin to show awareness of their gender identity |

| 2 years | Communicate awareness that their gender identities are incompatible with their legal designation at birth |

| 2 years | Begin to recognize gender stereotypes |

| 2.5 years | Many have established their gender identity |

| 4 years | Developed gender stereotypes informed by cultural messages about gender |

Figure 4. Milestones regarding gender expansiveness in very young children.

We do see evidence by a year that children are categorizing individuals by gender, looking at what we call secondary sex characteristics. This is because most of the time they're interacting with people with clothes on, so the attribution is different than when you're born, such as voice, facial hair or no facial hair, haircuts, and clothing style. Kids are taking this in and making ideas. They're already doing gender attribution.

By 18 months, we can see kids showing awareness of their gender identity. Many children at a very young age love dresses and love expressing themselves in what we as a culture call feminine ways or really love expressing themselves in masculine ways. I think we trust that so easily when it lines up with our expectations. I've seen people be so charmed by a little girl who was just learning to walk and wants to twirl and twirl and twirl, but not as charmed necessarily by a boy who wants to do the same activity.

By two years of age, they're communicating awareness about their own gender. For some kids that can line up with their legal gender designation at birth, the identity we've assumed they are based on that moment, even from an ultrasound. For others, even as young as two years, they can be expressing either a gender-expansive identity, which means a sense of gender that isn't within that binary, or transgender identity. We also see them recognizing gender stereotypes at two years. We see them already holding those stereotypes, and in those early years, we can often see those stereotypes fit the culture and the biases they're experiencing in the world. Sometimes that will lead to them telling others who they can and can't be, and will also lead to them telling themselves who they can and can't be in order to line up with the world that's been presented to them.

Toxic Effects of Binary Gender Messages

Julie Nicholson:

We want to share some statistics and information about how the binary gender idea, concept, and norm can be so harmful and how urgent it is that we communicate in our early learning programs messages of inclusion for children with all of the identities that they are bringing to us and the explorations they're having around gender. First and foremost, what is it to be an early childhood professional? Our responsibility and our ethical-moral obligations are to support children to feel safe, to feel a sense of belonging, and feel included in our care. That's number one. We need to assume that transgender and gender-expansive children are in all of our classrooms and in all our communities. We may not know yet in the early childhood years how they will identify as adults, but our job is to make sure that every one of them feels safe, included and has a sense of respect and belonging. What we know from research is that transgender and gender-expansive children are at a high end of the continuum of risk.

In 2016, the National Center for Transgender Equality published findings from the largest survey to date that had been completed with transgender adults. They had survey data that came in from 28,000 respondents. Looking at that data, we see the urgency in front of us in such a powerful and compelling way. The data detailed the incredible amount of discrimination, violence, and injustice that the transgender community faces every day. One of the statistics we wanted to bring out, which was incredibly sobering and just tragic, is that 40% of those who responded to the survey said that they had attempted suicide in their lifetime. That number is nine times the attempted suicide rate when you look across the US population. Of those respondents who said they did attempt suicide, 34% reported that their first attempt was before the age of 14. In these survey results, people talked about the tremendous amount of violence that they experience. About two weeks ago, I saw the results from an advocacy group, the Human Rights Campaign, that came out to say that 2021 has been the deadliest on record for transgender individuals in the US. There's urgency because people are being harmed and it's starting very young.

Here's the hope and the amazing gift of all of you being here to learn about this and leaning in because you care as professionals so much about what you do and you want to make sure that you do no harm. In that same survey, they found that one of the most powerful buffering factors for transgender children and youth was having a supportive family member. We know from research on trauma, resilience, and healthy child development that the most important thing we can do to support a child to thrive, especially a child who is facing stressors or even toxic stress, is to have a strong, consistent, attuned relationship. This is what we do every day in early learning. We are brain builders, brain architects, and we can buffer the stress of any child who is experiencing these kinds of outside stressors from the world that is telling them messages and the gender binary that they don't belong. We can counter that. We can create a space that they can come to every day and feel respected, loved, supported, and a sense of belonging. That is why we are all here, to make sure that the next generation of children, and even actually before then, has very different statistics. From birth, we want them to feel a sense of love and respect in our communities, in our early learning programs, and in their families.

Nathanael Flynn:

I'll just add, another thing that I think about with this is that the effects on transgender and gender-expansive kids are huge and we can make a huge impact, but there are also effects on cisgendered people, which is a term for people who haven't changed in their lifetime from their originally assigned gender. If you look at body acceptance among women, there are huge impacts. The statistic I'm remembering is that a large percentage of girls under 10 already feel like they should go on a diet.

Another statistic that I remember is regarding violent crime. If you look at violent crime and who's perpetrating violent crime and who is the victim of much of violent crime, one of the things that stuck out for me was that men were 90% of the perpetrators and 70% of the victims. That has a huge impact on their lives and what they're navigating. So often these things happen within spaces that we haven't thought through and the rules that we've created without necessarily even thinking about them. Sometimes we think that we're really helping because we don't want people to be hurt, but we don't want people to have to hurt people or to feel like they have to hurt people.

Shame and Hiding

Julie Nicholson:

Thank you, Nathanael. Such an important point that reinforces this idea that the gender binary is not healthy and doesn't support gender health for any of us. Nathanael talked to you about how the rules of gender begin early, before elementary school. Children start to read the world around them from a very young age and they really are picking up the cues and the social norms all around them from birth. They're learning about the rules of gender. A lot of children are learning from a very young age that they don't fit the rules. They often feel like they're getting cues, feedback, tones of voice, and information from caregivers, adults, media images, and things all around them that are telling them the way that you want to be, the way you want to show up in the world, the way that feels most natural to you is not allowed or not supported. They don't always understand why they're getting those messages, but it can lead to the sense of "something's wrong with me." We see that this can turn inward to children feeling a sense of shame, self-doubt, and feelings of questioning just at the moment when they're tenderly developing a sense of who they are in this world. They may wonder if they're loved, if they're seen, if they're acknowledged and validated and safe, and they're getting these little micro-moments throughout a day that say, "Not really. Nope. You don't belong here."

Another example is when we tell children to line up in our classrooms by boy and girl and that child doesn't know quite where to go. Those little moments happen over and over and over because gender is so pervasive in our world and can give them those feelings of something's not quite right. This can lead to these cycles of a lack of confidence, feeling like you have to hide a secret, not feeling good about yourself, and of course, this can turn into impacting a child's ability to learn and a child's ability to feel a healthy sense of their identity. We often can see this with behavioral challenges.

Two researchers, Payne and Smith, looked at elementary school children, but their research is very applicable to early childhood. They found for the most part that a lot of teachers are scared to find themselves teaching a transgender or gender-expansive child because they don't feel prepared and don't know enough about it to feel that they would know what to say or do. There's a real need for doing exactly what we're doing here, leaning in and learning. They also found that these elementary school teachers said they were waiting to change their curriculum, their practices, and the policies at a school site until a transgender child arrived. What we know is that research shows us that children start hiding when they don't neatly fit into the gender binary at really young ages because they do develop that sense of I'm not safe if I show my authentic self. We have children who don't feel safe and who don't see themselves in the environment. They don't feel that sense of inclusion. They're hiding and we have teachers who are waiting for children to show up. We can see the problem here.

Nathanael Flynn:

That same transgender survey pointed out that at least 50% of trans people in the respondents' group knew by the age of 10 that they were not and that less than 5% of them told anyone. Kids know, they listen, they are keeping track, and they're also autonomous. They're navigating for their own sense of self and their own space and where they can fit in and what they need to do to feel like they can belong.

Julie Nicholson:

We've found in our own Gender Justice in Early Childhood group and other research that transgender adults will often say they actually knew and had a sense of their gender identity being different than what they were assigned at birth from the age of two or three. This is why we have to start talking about this in early childhood. Sometimes you'll hear people say, "But they're so young, they don't even notice those things." We used to think like that but now we know that that's not true. Children notice all sorts of things. They're little scientists. They're always learning about the world and experimenting and trying to understand and make sense of how it works. They notice gender. They notice race. They notice all sorts of things.

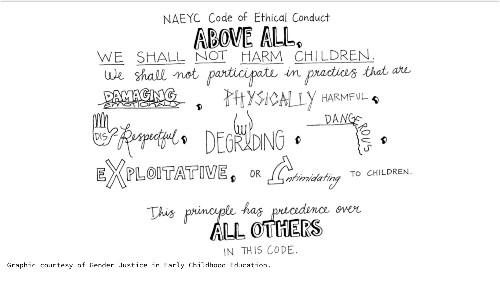

Figure 5. National Association for the Education of Young Children's code of ethical conduct.

The National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) has a code of ethical conduct that talks to all of us about some of the things that we should do when we sign up to work in this profession. We will respect the dignity, worth, and uniqueness of every individual child. We will respect the diversity and vulnerability of children. We will respect their dependence on us as adults for their safety, their sense of feeling loved, respected, and a sense of belonging in our presence. We will create healthy settings that support children across all domains of learning, including their social-emotional health. Above all, as it says in figure 5, we agree, that if we work in our profession, we shall not harm children.

We're not going to participate in things that are disrespectful, that intimidate them, or that are dangerous to them. In our commitment to not harm children it's important to think about misgendering children, whether intentionally or unintentionally. I don't think anybody intends to hurt children by misgendering, or perpetuating a gender binary and causing a child to go silent and hide. They're not intending to do that, but this principle says this is the most important one above all. What it is calling us to action to do is to say it's not only about intention, it's about impact. We have a responsibility to learn about gender expansiveness, about genders and gender identities, and to make changes in our practice so that we do no harm.

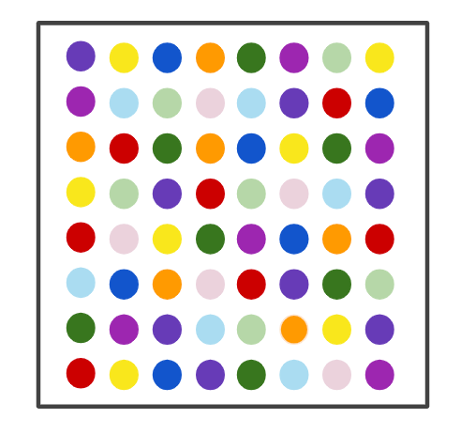

Nathanael Flynn:

We've been talking about this binary model (figure 3) with two ends where you are placed in a certain spot and that means all these things about you. This doesn't fit. What does? We want to encourage you to start thinking about each of those attributes and components of who we are. This includes our bodies, ideas, interests, curiosities, the way we feel dressed up, and the way we feel special. All of those things have diversity. In figure 6 we're representing this with lots of different colors versus figure 3 where there are only two. They can be the same or different between people and there's so much possibility.

Figure 6. Visual representation of components of who we are.

We also want to encourage you to open up those boxes by reimagining and reclaiming the contents and let them float out into that expansive sky and find their own space, as imagined in figure 7. Find your own meaning and your own truth. Think about the dots coming out of the box as different pieces of ourselves and all the things that make up who we are out there in the sky.

Figure 7. Visual representation of components of who we are being reclaimed.

Gender Expansiveness

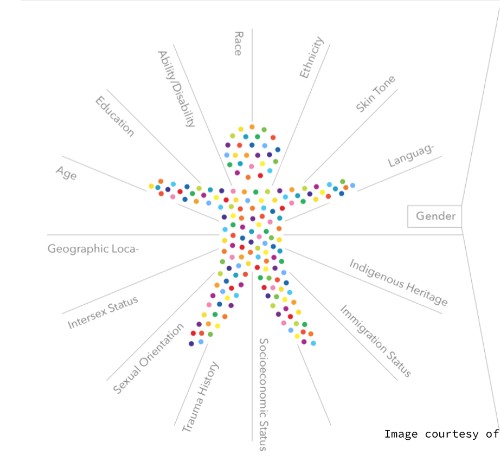

We see gender as complex, dynamic, individually-determined, distinct from sexual orientation, and related to other identities. We add distinct from sexual orientation because there is often an interrelatedness between sexuality and gender, particularly when we're little. Gender is a part of who we are, but it does not determine who we love. As I said, gender is related to other identities. We call this intersectional. Figure 8 shows examples of various identities.

Figure 8. Intersectionality of identities.

For me, as a white person with currently long hair, the clothes that I like, and my glasses, when I go outside and down the street and am interacting with the world, that is different than when I have short hair and am dressed up in a certain way. It also would be different for someone who is of a different race, someone who has a different gender identity, and whether or not they have different attributes. Our bodies can be different. We've talked about how our bodies are assigned at birth based on our physiology, including our genitals, but we also know that human bodies are diverse and that there are people for whom even that is not as straightforward as I was taught growing up.

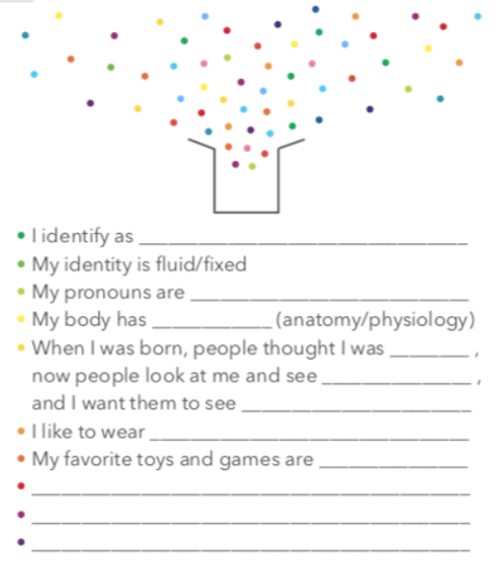

There are so many things interact with who we are. In addition to race, ethnicity, where you come from, what your family's background is, and your skin tone help make up who you are. The languages you speak, the languages you grew up speaking at home, and whether or not the language you work in is the language that you grew up with are part of you. Also included are your indigenous heritage, immigration status, your socioeconomic status, your trauma history, your age, your geographic location when you were growing up, and whether or not you moved during that time. All of these things are interconnected with our gender and everyone is navigating all of these pieces. We wanted to go a little bit deeper into gender expansiveness using the unfinished statements in figure 9.

Figure 9. Gender expansiveness statements.

Instead of thinking about how I came in this package, this is what I'm supposed to be, this is what I'm supposed to be allowed access to, and this is how I'm supposed to play, think about yourselves as who you identify as. In my case, I identify as male. Is your identity fluid or fixed, as in has it changed over time or always been the same? Those changes can be big, as some people change the words they use. Some people identify at some points in their lives as a girl and at some points as a boy. It also can be fluid when you become a parent. Being a mom or a dad influences who you are. Whether you're working or not can influence your identity.

There are also the words and pronouns you want people to use for you, such as he, she, they, etc. Think about your body and the anatomy that you're navigating. Surgery and other options allow you to change your anatomy over time, including if it needed to be changed because of wellness or illness. When I was born, people thought I was ____. Now people look at me and see ____ and I want them to see ____. I like to wear ____. Consider how you like to express yourself and your favorite toys and games. There's also space for you to tell us or tell the world what those other influences are because we're not going to be able to name everything for everybody. Everyone deserves the right to name for ourselves who we are and why.

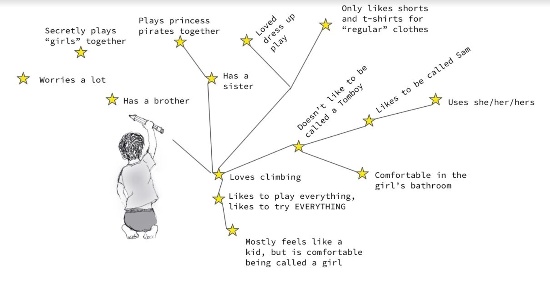

Gender Constellation

With that metaphor of letting it float up into the sky, we wanted to share the idea of a gender constellation as seen in figure 10. Instead of a list that we have to follow or even a checklist like the one that I just shared that brings these things up, we each get a chance to say, "These are my stars. These are my guide points. These are the things that are important to me." These are the relationships to them and to the world in that ever-expanding universe of who we all are.

Figure 10. Sam's gender constellation.

In this example, we see a fictitious child who mostly feels like a kid but is comfortable being called a girl. She likes to be called Sam. She uses she, her, and hers and wants other people to use those words too. She is totally comfortable in the female-assigned spaces, like bathrooms, but does not like to be called a tomboy even though, really, her interests are climbing and trying everything. She's deep into the exploration of the world and loves to play dress-up but really likes shorts and T-shirts for regular clothes. One of the things happening in Sam's world right now is Sam's sibling has come out and has transitioned. Sam is getting to erase and let go of some stars that really didn't work in her family unit. She gets to erase worrying a lot about her sibling. She gets to erase telling people that she has a brother while secretly playing girls together when their parents, family, and teachers aren't looking. Now she gets to play with her sister. She gets to tell the world she has a sister and they get to play their princess pirates together and let everybody know about their beloved games. That's one way a gender constellation can look. It's one way that this child can have the autonomy to change the dots and change the lines and see that those things are interrelated and interconnected with their family, the circles of their community, and the stories in their world.

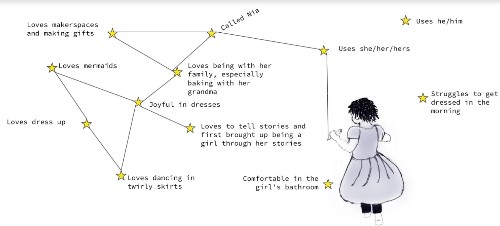

Figure 11. Nia's gender constellation.

Another example is this child in figure 11 who has erased some stars already. They're just floating out there and not part of the constellation anymore. Those are words like he and him and experiences like struggling every morning to get dressed because now she gets to be in those dresses that bring her joy. She loves being with her family, especially baking with her grandma. She loves makerspaces and loves making gifts. That feels like such an expression of who she is and of something that she's gotten to draw in without it being a stressful thing anymore. She loves dancing in her twirly skirts and loves mermaids and dress-up. As she's made this change at school, she's drawing in that line. She's working so hard to find that comfort level in the spaces that she feels were hers but that she wasn't allowed in until she got to tell her story and find adults who would listen to her and find adults who helped her family listen to her. She's drawing in that line to being comfortable in the girls' bathroom. You can imagine what might come after that with time.

Take a few minutes to draw your constellation. Your constellation might look a lot like what people thought it would when you were growing up. Your constellation might look really different than the person that sees you next would think it was. Take that time to think about what your stars are. What's so important to you? What helps you feel like who you are? What helps you express who you are? If there's anything that you've been feeling is supposed to be in your constellation but you really wish wasn't and you want to find a way to start to use that eraser, you have that autonomy in your own life to change it. For me, that was feeling like I have to keep myself a secret. Getting to erase that was amazing. Take a moment to think about what might be in there and what might be lurking.

Applying This Knowledge to Support Children

Julie Nicholson:

We hope you took time to draw your constellation, shifting and expanding beyond the gender binary to understand this complexity of gender that's dynamic and intersectional and where you have agency to draw who you know yourself to be. Those are all really important strategies for creating a gender-inclusive and gender-equitable environment and supporting gender diversity.

Shared Goals

Now let's think about how can we apply some of these ideas about gender and gender diversity to support the children that we're working either directly with or on behalf of. The first idea is so simple and yet so absolutely profound. It is the importance of relationships. We already talked about why we get into the work we do, how we love supporting children, and how we want all children and families to thrive. So central to our work is creating an environment where children feel safety, feel respected, and feel a sense of belonging. We know that consistent, supportive, caring, attuned relationships are the most important thing for all children, end of story.

What does attunement mean? Dr. Peter Levine and Maggie Kline talk about how when you attune to a child, you help that child feel felt. That child feels that sense when you are in their presence and when you are talking to them that nothing is more important in the world than who they are at that moment in time, not who they should become when they change this or that, but who they are at that moment in time in the classroom, program, or during your home visit. They feel that you're attuning to them, accepting them, bearing witness, supporting, and seeing them through strength for who they are. You are showing them such respect by focusing on them so that they feel felt, visible, and acknowledged. That's where we give children that sense of you belong in this world. We're so happy you're here and we are 100% with you and supporting you.

If we're going to bring a sense of attunement to our relationships, one thing we have to let go of is worrying and wondering about if a child likes to put on skirts, what does that mean for them in the future? Is this child transgender? Are they going to be? It is not necessary to think about these questions and worry or wonder about them. Our responsibility is to make sure that child, no matter who they are and how they show up, feels respected, supported, and have a sense of belonging and that attuned excitement and engaged attentiveness that we are giving them. Focusing on the here and now is the number one thing we want to start with.

Self-Reflection

We also know that all work and all change starts by first tuning inward. If we want to change our practices in the classroom, change the way that we set up our curriculum, or how we engage with families, first we have to understand how we're showing up. Remember, it's not just about what our intentions are, it's about our impact. We encourage you to start by asking yourself some questions to reflect on who you are and what your beliefs are and what your experiences are around gender. Our book, Supporting Gender Diversity in Early Childhood Classrooms: A Practical Guide, goes through an audit tool that has lots of ideas and questions, but I'm going to share a few here.

- How did you learn about gender?

- What gender norms were you taught about what it meant to be a boy or a girl or to be gendered in your family and your community?

- What was expected of you?

- How did those gender norms benefit you and how did they hold you back?

- What feelings come up for you when you think about changing your thoughts about gender?

- Are there things that you love about your gender?

- Were there times that you felt really affirmed and you've felt a sense of belonging in your gender?

- What are some ways that society has hurt you or the norms have limited you and left you feeling like you weren't seen, you weren't validated, you weren't acknowledged around your gender?

There are many things that you can do by looking around your classroom and asking yourself questions. The audit tool goes through these questions and more. How do you arrange your classroom? Are you looking at your bins and making sure that clothing bins are not labeled by boys and girls which reinforces that binary? What about cubbies? Are you separating by the gender binary and if so, can we think of another way of doing that? Does your school library have books that represent diverse people of all types, including diverse genders? Do you notice how you use gender throughout the day and catch yourself if you're asking children to line up using boys and girls as ways to separate or transition or to represent and talk about children? On your family intake forms, do you use gender-neutral language like family members instead of mother and father? Do you allow families, parents, and family members to name and express their child's gender in their own language? These are just a few ideas of ways that you can begin to do that auditing that brings your awareness to how you're reproducing and talking and socializing gender and how you might want to do things a little differently to be more inclusive.

Connect with Children and Families

Nathanael Flynn:

Another piece in this work is connecting with families. We wanted to start with you and then think about the relationships in the children's lives because young children aren't alone. They have a context. All of us have a context, but the family context of young children, in particular, is so important and so impactful. Think about building those relationships and building trust and be ready to create contexts within those relationships to have vulnerable conversations. I think that's such a core part of early childhood education. Many of us have built up skills of how to make those precious moments of pickup and drop off into so much more.

When it comes to the vulnerability, joy, and creativity that can be gender, it's helpful to think about those relationships and the expertise that you carry. It can be a voice for giving people space to be seen and heard and loved for who they are. Sometimes that is telling the story that shares your joy and their curiosity and creativity, sometimes it's sharing pictures of their joy when they're dressing up, and sometimes it's just finding moments to have conversations about the hard things that happen.

We also have the power within these relationships to make space for all of us to be ourselves. One of the stories I've heard a lot is about restricted play, whether that's parents asking that kids not be allowed to play a certain thing in your classroom or saying they'd never have that at home. Some things I hear are related to gender, such as the idea of asking that girls not be allowed to roughhouse or climb trees but their brothers are allowed to do that. It might be vice versa discouraging boys from cooking, playing with dolls, cleaning, and all of those daily care things that we all deal with in our lives one way or another. We can be there to have those conversations about how doing these things is a part of being ourselves. Children are exploring and mirroring what they see. They're getting a chance to try things out and that's okay. Both it's okay, this doesn't mean something about them, and it's okay if it does mean something about them. Building relationships where you can have conversations that help parents attune to, connect to, and see their kids is so crucial to this work.

Listen to Children

Another part of this is listening to children. We've said this in different ways, but we really wanted to call out this Diane Ehrensaft quote, "It is not for us to say, but for the children to tell." So often when we listen to children asking questions, telling stories, and wanting things, it leads to such wonderful connections with kids. For example, a child asked for braids and got to choose the color of the scrunchies. That was not determined by the adult and the child had the joy of getting access. It doesn't determine who this kid is, but sometimes it does provide an opening for a kid to start talking and to feel like their voice will be heard. As Julie said, we're not trying to determine that for them. We're trying to listen.

Julie Nicholson:

We really need to give them credibility when they talk to us. We need to listen, hear, and trust that what they tell us is something that we want to take seriously and acknowledge and believe. Many have an image of the child in early childhood and often say, "Oh, isn't it cute that so-and-so is saying...," but along with that, there's a sense of I'm not going to give it a full level of credibility. It's a form of injustice when we do that and don't trust children to tell us who they know themselves to be at that moment in time, so we want to listen and hear. When I say hear, give them that full respect and credibility that what they're saying is meaningful to them and we're going to take it with all of the seriousness in which they are and intentionality in which they're sharing it.

Share Information

Nathanael Flynn:

The other piece of this is sharing information, which is a broad category for a lot of different topics. One of those pieces of information is found in objects. I'm thinking about the child in figure 12. It's a little bit hard to see because she's looking down, but the joy on her face when she gets to put together her outfit and try on and explore and just be in the moment is wonderful. In your classroom, that can mean you have all of these gender signifiers or it can mean that for your classroom, children will limit themselves to only playing with the ones that are assigned to them, so maybe you take them out. For this particular kid, getting to make a collage of everything and feel it all was perfect. For another kid, getting to start from scratch might be perfect. For another kid, getting to have access to that tie and feel like a grownup may be perfect. It may bring out both the joy and euphoria of being a person, as well as give them the tools to say, "Hey, this fits. This is me."

Figure 12. Child playing dress-up.

Another piece of this is that there are stereotypes in the world and in our literature. Notice these stereotypes. There are stereotypes in things we accidentally say. I can think of a coworker who recognized that each time a boy picked up a bag, she would say, "Oh, you've got your briefcase and you're going off to work," and each time a girl picked up the same bag, she'd say, "Oh, look, it's your purse. Are you going shopping?" At the moment when she recognized that she'd been saying something without thinking about how men work and girls shop, she said, "I'm doing this thing and I don't want to be. I want to replace my behaviors." Maybe for her that was saying, "Oh, look at you. You've got your bag. Where are you off to?" and trying to take out the gender attribution because she didn't quite trust herself to talk about possibilities yet. That was her first step. For some other folks, it's reading a book and thinking, "Is that fair, or is that true?"

Thinking about parenting, I remember reading Eric Carle's book, Does a Kangaroo Have a Mother, Too? It's all about how everyone has a mother. We know that's not true for so many different reasons. The kids for whom that's not true are left out and don't exist by this book, so maybe we take that book out, or maybe if that book has been in their lives forever we can unpack that book and say, "Hmm, but what if we wrote a book about families? What would we want in there?" That's an example of how you can act to interrupt bias. You can change the narrative in the world. Sometimes that's in big ways, like doing a project about a book, and sometimes that's in little ways by saying, "Hmm, is that true?" or by modeling differences. When we don't do something to interrupt the bias that comes into our classrooms, we are perpetuating harm. That bias can be sneaky, unintended, and completely unintentional. We can take time to slow down to think about it and to do as much as we can to interrupt that bias and create a narrative about equity and attunement and care.

There's also an important piece about sharing information about gender diversity in age-appropriate ways. It doesn't mean you need to lecture them on the word "transgender" and what it means or the word "cisgender" and what it means. It does mean finding a book such as I'm Jay, Let's Play, by Beth Reichmuth. In this book, Jay has a skirt and does different activities. The child's pronouns are never mentioned, which could give a chance to talk about using different pronouns. Another book is When Aidan Became a Big Brother by Kyle Lukoff. This book can give you a chance to talk about children's advocacy for each other. I encourage you to look these books up. There are books out there that have stories in which kids get to talk about themselves or be themselves and they aren't necessarily within those pieces. It's also looking at books like Goodnight, Goodnight, Construction Site by Sherri Duskey Rinker and changing the pronouns.

Give kids access to that ever-expanding universe of how we get to talk about ourselves. For me, it was a thing that I had to practice, a thing I felt scared to say in the school I was working at in the time, saying we can be boys, girls, both and neither, and that it's not up to me, it's up to you about who you are. You get to tell me who you are. For me, that meant starting with my boss with that conversation before I started with the kids. It's so important to keep taking those steps. The other piece that we really wanted to highlight is to not think about this as one circle time or one diversity Tuesday or one isolated unit, but that this is a part of all of our days. This is a part of serving food. Think about all those levels of the day and where the gender binary might be creeping into your thinking, whether that's saying, "Oh, boys and girls, let's do this." A friend of mine's child said, "So, excuse me, but where do the kids go?" This is part of our whole routine, otherwise it gets very isolated and that can perpetuate bias in young children's minds.

Julie Nicholson:

We have a list of books on our website. Those books that Nathanael mentioned are fabulous and we have a whole list and how to select books. We thought we'd close with this quote.

Every young child has the right to feel seen and heard as their authentic self by the adults responsible for their care. A relationship between an adult and a child can be loving and caring without being attuned if the child is experiencing something the adult can't see, doesn't understand, or interprets significantly differently than the child does. Early childhood educators are ethically obligated to create environments where all children are visible and responsively cared for.

Our book, Supporting Gender Diversity in Early Childhood Classrooms, has a lot of ideas for classrooms and our website, genderjusticeinearlychildhood.com, has some free downloadable resources for you.

References

Citation

Flynn, N. and Nicholson, J. (2021). Supporting gender diversity in early childhood. Continued.com - Early Childhood Education, Article 23763. Available at www.continued.com/early-childhood-education