Editor's note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar Pediatric Abusive Head Trauma: Recognition, Prevention, and Long-term Impact, presented by Alison D. Peak, LCSW, IMH-E.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Examine the legislation requiring PAHT continuing education, its origins, and its intentions.

- Identify the prevalence of PAHT, warning signs, and long-term outcomes.

- Analyze effective prevention programs and their role in preventing and mitigating PAHT in communities.

Introduction

We will talk about some heavy stuff today, and I want to ensure you know I will share stories as I share content. I encourage you to slow down, recognize your thoughts and emotions, and take care of yourself as we walk through this together. My great passion is working on behalf of children from birth through age five and their caregivers, working clinically, programmatically, and systemically on behalf of little ones and those who care for them. I also want you to know that I'm a social worker. I identify deeply as a social worker and love my work. It is part of who I am and all the things that come with me. It'll be a big part of my perspective and the stories I tell today.

I also want you to know that in the process of becoming a social worker, I spent four years as a floater in an early childcare center, so I have also been in early childhood classrooms. I remember working with 15 two-year-olds simultaneously and all the pieces that come with that. I remember those kiddos who were the first ones in the door, the last ones to leave, and who often spent more time with us than they did with caregivers at home. Even in that place of having children in your physical presence for long periods, there are still questions about what happens when they leave and what the rest of their day looks like.

This course is for both social workers and early childhood educators. I'll do my best to wear both hats and keep in mind all the different stories and perspectives you bring. Before we jump in, I want you to take a moment. I'm going to guide you through a grounding activity. As I said, we're going to deal with some pretty heavy content today, so I always like to make sure that we're deeply connected to our space and place and are present as we dive into these things.

I invite you to find a comfortable space. Make sure as you sit that your bones are deeply connected to your chair and that your feet are firmly grounded. After you read the instructions, close your eyes or stare softly about six feet in front of you, whichever is best for you. You're going to take three deep breaths. As you breathe in, count to four, then hold the breath for a count of seven, then breathe out for a count of eight. Do this three times, then come back to the course.

Pediatric Abusive Head Trauma (PAHT) in Kentucky

In 2010, the Kentucky General Assembly passed a bipartisan bill requiring many disciplines to receive consistent training in pediatric abusive head trauma. That original piece of legislation is tagged as Kentucky House Bill 285. That legislation has now been morphed into state policy and can be found in various locations throughout the state code. The original legislation is tagged as Kentucky House Bill 285. At that time, the goal was to increase recognition of signs and symptoms of pediatric abusive head trauma, increase prevention efforts for pediatric abusive head trauma, and ensure that professionals who interact with young children are aware of the potential outcomes of pediatric abusive head trauma given its considerable relationship to child well-being and child abuse.

In the state of Kentucky, the following people must be trained in pediatric abusive head trauma.

- Law enforcement

- High school students

- Inmates in state penitentiaries

- Guardian ad litems (attorneys specifically for the child welfare sector)

- Prospective adoptive parents

- Childcare providers

- Pediatricians, radiologists, family practitioners, trauma physicians, and family medicine physicians

- Physician assistants and nurse practitioners

- Paramedics, medical technicians, and first responders

- Nurses

- Social workers

I think it's intriguing to think about how, as individuals get closer to years in which they are no longer children but are becoming parents, we are preparing them to know what it means to take care of littles and show up on behalf of them.

What is Pediatric Abusive Head Trauma (PAHT)?

First and foremost, what is it? Pediatric abusive head trauma describes a constellation of signs and symptoms resulting from violent shaking and impacting an infant's or small child's head. In mainstream media, this more often gets referred to as Shaken Baby Syndrome, but the medical terminology is pediatric abusive head trauma. This definition clearly states that this does not occur and is not caused by general play, falls from a couch, or other things of that nature. Pediatric abusive head trauma is one of the primary physical child abuse incidents that occur in early childhood.

PAHT in the News and Media

We first saw pediatric abusive head trauma come into the news and media in 1962. At that time, a physician named Dr. C. Henry Kempe was beginning to identify a connection between aggressive and neglectful parenting and long-term behavioral and mental health symptomology within children who were the recipients of that aggressive and neglectful parenting. Sometimes in the literature, it gets referred to as scary parenting, based on the idea that the caregiver is the source that the child is afraid of. We think about those consistent moments when caregivers are large and out of control.

As I mentioned, we don't see this constellation of pediatric abusive head trauma with somebody who fell off the couch. Also, we know that all parents get upset sometimes, and kids get yelled at. However, at the other end of the spectrum, the parent may be the person children are afraid of and cannot seek comfort from. Think about really exaggerated, aggressive behavior, including physical abuse, intense emotional abuse, and neglect. Also, keep in mind the intense interpretations of a parent about a child's intentions.

Dr. Kempe's study in 1962 began to categorize these symptoms as battered child syndrome. It was revolutionary for the early '60s to think that child abuse occurred in all types of homes and all types of environments. This was not just seen in families experiencing extreme poverty or only in families with single-caregiver homes. They saw this show up in lots of places regardless of socioeconomic status or kind of caregiving dynamics. This laid the initial foundation for child abuse laws and mandated reporting. When this study came out, the recognition of battered child syndrome prompted legislation to realize that something had to be done. They couldn't just leave things where they were. There needed to be a response to this aggressive and neglectful parenting that deeply impacted these children.

A paper published in 1972 proposed the idea that the brain, as an organ, could sustain injury from being thrown about. They categorized it as whiplash-shaken infant syndrome. It also identified a triad of symptoms observable by X-ray that may or may not accompany other signs and symptoms of abuse, including cerebral swelling and hemorrhaging. Imagine being in a car accident, busting your head open, and needing stitches. There may not be an external manifestation of what is clearly an internal injury.

In 1997, a British nanny was charged with the murder of an eight-month-old baby in relation to a series of symptoms that physicians and police called shaken baby syndrome. This case sparked a series of concerns and awareness from the greater US public about shaken baby syndrome and its potential impacts on children and child well-being. We see this evolution of language from battered child syndrome to whiplash shaken infant syndrome, to the concept of shaken baby syndrome, and, currently, pediatric abusive head trauma.

I was a child when this occurred and remember it fairly clearly because I had an infant cousin at that time. I remember my family being really cautious, more so than they had been in prior years, about who got to hold the baby and where they were standing or sitting when holding the baby. There was an increased awareness that something terrible might happen because of the increased conversations around shaken baby syndrome.

Within broader news media, there is increasing conversation about the role of investigation in child abuse reports. People are slowing down to ask, what is happening, and what is it that occurs in families when there is the experience of pediatric abusive head trauma? Current media is also highlighting that in previous years, people were quick to identify a "victim" and a "culprit" without allowing for the due diligence of an investigation that holds multiple outcomes as a possibility. It is rare to have clear evidence without proof of pediatric head trauma. It's unlikely we're going to catch it on camera. One of the things we are increasingly aware of is that some of the symptoms we begin to see in early pediatric abusive head trauma may be related to an event that occurred weeks or days prior and may not be the thing that happened most recently.

Child Well-Being

Kentucky

Kentucky ranks 37th overall in child well-being for the United States. It ranks 38th in economic well-being for children but 26th in educational well-being for children. It ranks 42nd for family and community well-being. This ranking highlights an above-average presence of alternative caregivers, such as grandparent or kinship placements, single-parent homes, and high poverty. This does not include children engaged in the state child welfare system.

Nationally

Nationally, three out of every thousand children are in foster care. On average, the US spends about $1.3 billion on foster care placements, care, and associated adoption costs every year. Child welfare is not cheap. For the nation to step in and take care of vulnerable children and families comes at a price. I live and work in Tennessee, and right now, there are nearly 30,000 children in foster care in the state of Tennessee. While it might only be three out of every thousand, that is still a significant number of kids.

Regarding the connection between child welfare and child well-being, we want to consider those placement disruptions associated with foster care or other similar arrangements are generally connected to a six-month regression in development for each placement disruption. Statistically speaking, if we have a three-year-old who's removed from their primary caregiver and placed in a foster home, that's one disruption. If that foster home says, "I cannot manage this child. They're going to have to go someplace else," and they are then placed with another foster home, that's a second disruption. Then let's say, heaven forbid, that foster home says, "Oh my goodness, I have had an elderly parent who now has an end-of-life need, and I'm going to no longer be able to foster," and that child moves again, that would be the third disruption. Some of our kiddos in child welfare can be disrupted fairly frequently. It is not uncommon that in most states, children in foster care have an average of three and a half placements in their first year in child welfare.

If a child has three placement disruptions, and we think about that from a mathematical standpoint, that would be an average regression of 18 months' worth of development. That means we are in a place in child welfare where the children in foster care often function as children much younger than their chronological age and present with some significant challenges. Some states have what can generally be referred to as privatized foster care. These states will have programs or nonprofits where parents are allowed to give temporary custody to an agency instead of their child being placed in child welfare for things like rehab stays, short-term incarceration, and homelessness that appears as though it will resolve at some terminal point. Those may not be technically foster care, but they would be very similar. Those kinds of placement disruptions become connected to that six-month regression.

Taking care of our kiddos who've already had experiences of trauma and potentially scary parenting becomes really important because the more there is disruption, the more compounded we see the impact on development and delays. When possible, children are best raised in the care of their families. When that is not possible, we look for permanency in other settings. One of the major goals of child welfare is to try to keep kids in homes and connected to families as much as possible. Awareness, prevention, and intervention opportunities around pediatric abusive head trauma reduce the likelihood of child welfare placements or duration of placements and reduce the cost of long-term out-of-home stays.

Child Welfare

Kentucky

In 2020, 66.9 per every thousand children in Kentucky were the identified minors in a child welfare investigation. Remember, I said about three out of every thousand children go into foster care, but about 67 out of every thousand have some related Child Protective Services (CPS) report. CPS is generally a division of the child welfare system. Of those roughly 67 per thousand kids who were part of a child welfare investigation, about 17 of them had a substantiated abuse finding.

A substantiated abuse finding can be defined in a couple of ways. When a child welfare report comes into the mandated reporting system, it becomes the responsibility of that part of the child welfare system to identify whether or not a report is "valid." There are lots of reasons why a report might not be valid. There are times that folks have told me that they filed a report because they saw a caregiver spank a child in a grocery store, but they didn't know the child, didn't know the caregiver and didn't have names or any information. While they called that in, at the end of the day, the child welfare system couldn't figure out who it was. There's no way to connect it to an individual or to an option to investigate further. All of those calls pretty much get screened out because there's not enough information there to do anything with them.

There are also calls that get made to child welfare that may not rise to the definition of what is considered dependent abuse or neglect. I can think of reports I have filed that did not meet that qualification. There have been times when I was very worried about a family's dynamics and very concerned that choices were unhealthy. That can be difficult to communicate. Unhealthy decision-making does not necessarily equate to unsafe and may not leave bruises or indicate that a child doesn't have a place to sleep and a roof over their head. Those can be screened out.

There are many other reasons a report may not be "substantiated." But a substantiated abuse finding means that the state agrees that there's an issue and that we need some support. Those supports can look like lots of different things, such as foster care or additional services in the home. Of those 17 per every thousand children in Kentucky with a substantiated abuse report, not all of them entered the foster care system. However, of those roughly 17 per thousand, about one per every hundred thousand was specifically a child abuse-related fatality, meaning that the abuse had been egregious enough that the child did not survive. For 2020, there were about 16,750 children in foster care across the Commonwealth. Of those, about 15% were under a year old, and about 47% of all foster care children were age five or younger.

Nationally

I also highlight that, nationally, about 16% of all children engaged in child welfare were one year or younger. Nationally, 42% of all the children in child welfare were age five or younger. Kentucky is not alone in this. Consistently across all the states, infants and young children have the highest rate of engagement with child protective services and the highest rate of removal.

It's a curious statistic to take a step back and reflect on because, most of the time, when folks think about foster care, they think about school-aged children and often think about teenagers. They may have a picture in their head of a 15-year-old who needs a place to go because things at home are so intense and difficult. While nationally, 58% of the kids in child welfare are not aged five or under, the single largest age bracket engaged in child welfare is birth to five. Most of our kids in foster care are young. Most of them are in developmental spaces where they cannot fully give words to their experience or have the kind of cognitive development to connect cause and effect. They cannot understand how they got here and where they are.

Why?

Children aged five and under are at the most risk for CPS investigation and removal because infants and young children are much more dependent on caregivers. When we think about allegations of neglect that are substantiated to removal, it may be the difference between healthy and safe. A 10-year-old can find their own Pop-Tarts. While that may not be great, and it may not be the nutritional density that we would hope for, the reality is that they're fed. Often it is because they feed themselves. A two-year-old won't do that.

They are also less verbal or nonverbal than older children, meaning they cannot be an active narrator about their experiences. I think that makes pediatricians, CPS workers, and others involved aware of what may be happening in the world of young children. Whereas, I think, for older kids, there's some expectation that they'll tell us when something is wrong.

Littles have big emotions in little bodies. As part of the developmental trajectory, even with typical developing, best-case-scenario kiddos, the number of meltdowns children have between birth and 18 continuously decreases. Even more emotional kids have emotional stability the older they get. But littles have a lot of big feelings. One of the statistics we use in ZERO TO THREE talks about how the average number of meltdowns for a two-year-old in a day is about one meltdown every 24 minutes. It is typical that about every half an hour, a two-year-old is completely melting down with all the tears and feelings. We know as kids get older, that tends to dissipate. They can better internalize their coping skills, self-regulate in those moments, and hang in there a little bit longer with all those big emotions.

Children under five are also more at risk for CPS investigation and removal because they've got first-time parents. Often, families will tend to stabilize with repeat children, and first-time parents are often overwhelmed. Babies may very well find themselves welcomed into overwhelmed caregiving systems, where there may be a parental mental illness and parental substance abuse, and grandparents who don't live close by or have their own mental health and substance abuse concerns.

Coming into those spaces, I frequently say, "All babies mean change." The most wanted and planned-for and hoped-for babies mean change and change is hard. I had a meeting this morning with a colleague, and I said, "How's your week been?" She said, "You know, four-month sleep progression plus a time change is not my favorite weekend." Even the most wanted and planned-for babies can be hard. When this may have been a baby who was not planned for or when we think about systems that are already overwhelmed with mental health concerns, low socioeconomic status, and substance abuse concerns (risk factors), welcoming a very needy, very dependent, nonverbal being into the space is often a tipping point.

Across all states, it doesn't really matter where you are; the single largest category age-wise for kids at risk of child abuse is under six weeks of life. The first six weeks of life is the most volatile time and the most likely time for an incident of physical child abuse, specifically for that physical child abuse to be pediatric abusive head trauma.

Babies

As I said before, babies mean change. Even wanted, adored, and loved babies mean change. Change can be really hard, and a new baby is a major adaptation. I think about others in my world who say, "I wanted this baby so much, and I never leave my house. I haven't seen anybody else in weeks. I wanted to apply for this promotion, but it would be more time, and I don't have it to give." Even in the place of intentionally thought-about children, there's change. When we have not had the privilege of slowing down to think about what a baby may mean, that change will be even harder. I use the word privilege intentionally because when we think about insight and reflection, there is truth about it being a privilege. Not all of us live in spaces without risk factors such as mental health concerns, substance abuse, low socioeconomic status, incarceration, legal charges, etc.

When working to survive, we don't often slow down to think and wonder what this might be like. How might it be for all of these things to be different? Because we're just trying to keep a roof over our heads and keep going. Hold in mind that babies mean change. Also, hold in mind that the process of becoming a parent is one of the most emotionally evocative life changes that occur. It's a real dynamic shift to suddenly have someone who needs you far more than you have needed other folks. In that process of being needed and needing help, becoming a parent calls back to the parent's own experience of being parented.

When we've got a parent who had their own history of early neglect, abuse, or emotional abandonment, then when there is a new baby, there is a deep remembering that, oh, I want to do all of these things for this kiddo that I did not get, and grief that they did not get those things. Or, we see parents who say, "Well, it was good enough for me. I don't know why it wasn't good enough for them." We hear that a lot, and so in the process of becoming a parent, we call back to what it was for us to be parented and make decisions from that information.

Early childhood has a certain aspect of universality that nothing else has. Out of everybody who completes this course, there will not be a piece that everybody's ever had. Not everybody will have experienced psychosis. Not everybody will have dealt with a substance abuse issue. Not everybody will have a learning disability. But every single person who accesses this material will have at one time been three. In that space of thinking about infants and young children, there is a universality that also calls us to think about what it was for us to be little and how people cared for us.

I made the caveat early on about leaning into how you are feeling and thinking. Take time to take care of yourself. Take a moment to get up and walk around the room. Find some water and come back. The reality of the parallel between our work, the children we see, and the experience of what it was to be children ourselves is closely connected. As we walk through the next part of our time together, I will tell some stories. I mentioned that I'm a social worker. What I don't know that I named quite prolifically is that my clinical specialization is in severe early childhood trauma, and a lot of that looks like physical abuse.

I always find it very important to name at this point that some of my stories can be quite intense to hear. For me, they are humans, and so I know all of their stories. I know the funny moments in addition to the sad moments. I know the things that make them great and wonderful human beings. You all will get a snapshot for the purposes of educational demonstration. Sometimes that's intense material, and I want to name that outright.

The First Six Weeks

When we think about the statistic that the first six weeks of life are the highest likelihood for an incident of physical child abuse, most often pediatric head trauma, there are a number of reasons. One is that birth can be very traumatic. Frequently, unexpected complications, surgeries, the sense of feeling out of control, or recovery can take longer than expected. All of those things can be frustrating for caregivers.

When I think specifically about labor and delivery complications, mama may be out of pocket, those complications may result in longer healing time, or it may mean that mom is sleeping or has her own physical limitations. I think about a friend of mine who ended up having an emergency C-section and, six weeks later, had to have her gallbladder removed. She didn't sit upright for about 2 1/2 months. Some limitations from unexpected complications can put increased stress on an alternate individual. Sometimes that might be whoever that second biological caregiver is. It may be support from extended family called in, a nanny, or some other type of interim childcare that was hired. That person then is going to be in the position of the primary caregiver for that tiny baby.

The other piece, when we think about the experience of the first six weeks of life, is that the body releases several hormones immediately upon giving birth. The first we'll talk about is oxytocin. Oxytocin is the hormone that tells us to love babies. I always make this joke, and I inevitably get somebody who says, that's not accurate. But brand-new newborn babies are generally not that cute. If you take a step back for a moment and think about it, they're red and slimy, and they're really squished and swollen. Babies get cute after a few weeks as they fill out and have their appropriate color. But, right after they are born, babies are not particularly cute. Again, someone will always argue with me that their newborn baby was very cute, but I will also say that I think that's the oxytocin talking.

The hormone oxytocin that's released at birth is the thing that tells us from an evolutionary, biological state that we're supposed to love for and care about babies. It is the hormone released when you see a picture of a baby, and everybody in the room goes aw. It's a collective shared experience because our brain says, "Oh, that's a thing you're supposed to take care of. That's a thing you're supposed to love." It also happens with dogs. I would say it happens with cats, but I'm not a cat person, so I don't register with that experience. So oxytocin gets released, and we have this kind of euphoria that happens with a deep biological sense to take care of this being.

The second thing that happens is that your hormones crash into a pre-pubertal state. Think about that. You go from age 30 to 13 in about 45 seconds. That can make people fairly moody. For most folks, there's a period of about two weeks of what gets referred to as the baby blues, but for some folks, it can trigger some significant mental health concerns. Both of those pieces together, the hormone release and the possibility of birth trauma and complications, can increase our risk factors and shift our stress.

The other piece is the baby themselves. Babies are not blank slates. Babies come into the world with their own personalities. With that personality, they also bring parents' perceptions of who that baby is. In the first six weeks of life, babies' primary goals are to try to get in a pattern around breathing, eating, and sleeping. That's the goal in the first six weeks, meaning we don't have a pattern in those first six weeks.

Sometimes they're sleeping a lot, not sleeping, or cluster feeding, where they eat about 20 minutes apart and then don't eat for six hours. They're just trying to figure out how to breathe and get into a pattern of being. In the first six weeks, babies often cry excessively without the ability to be soothed. In infant and early childhood mental health, we talk about the concept of being with. One of the examples we give is the process of being the caregiver to a young child, walking the floor, and having no solution. If you have been the caregiver to littles, you know what it is to be up at 2:00 AM, pacing up and down a hallway with a screaming baby, saying, "I don't know what you want. I'm still here, but I have no idea what you want." We've tried all the things we know to try. In the first six weeks, the periods of really intense crying without the ability to be soothed are much more common. Also, during that time, babies don't sleep regularly. They're not predictable and are not yet in a pattern.

That also means that caregivers don't sleep regularly. Think about caregivers who may have had a traumatic experience. Their hormones are off and may have triggered some mental health episodes. Now they have only slept for three hours in the last 24, and their baby is screaming at the top of their lungs. They don't have any paid maternity or paternity leave. They're also concerned about whether or not they're going to make rent because Mom can't go back to work because now she has all of these complications from surgery. All those factors together in the first six weeks can make for a really intense perfect storm.

It is not uncommon in early childhood that parents perceive babies as fussy. There's always the reality that parents perceive their children to be in specific ways that the rest of the world may not. I think about some of the kiddos that I work with clinically that parents will describe as difficult, and they're no more difficult than anybody else. This is not an early childhood example, but we recently had a family who was extremely frustrated and kept referring to their 14-year-old as distracted. The 14-year-old was on Snapchat and losing track of time. They weren't distracted. They were just 14-year-olds on electronics. The same is true with infants. Some families perceive their baby to be fussy and, internally, feel less successful at calming that baby or soothing the process.

We talked about the oxytocin release right after labor and delivery. Remember, this release starts the biological process of bonding that leads us to an attachment relationship. There are situations in which we know that caregivers will produce less oxytocin. These include a history of major depressive disorder, severe mood disorders, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. By virtue of that, this immediate bonding hormone may not be as strong.

When we know that families have support in place and they've got good resources, many families navigate that and can overcome and find their way. But that's not the case for all of our families. While the body will produce oxytocin as a biochemical reward for taking care of something and loving a thing, there's also the reality that the body produces cortisol whenever we're super stressed. When we're stressed, that cortisol comes out, and it says, "Something is wrong. Something is wrong. You have to fix it." I often tell my little kids that it's our brain's fire alarm. It's the thing that beeps and tells us something might not be safe.

In that first six weeks, we're trying to find those cues, develop our patterns, and be in that place. As the baby is soothed and parents feel successful, oxytocin produces the biochemical reward that says, "You did it. See? We did it together." Babies also produce oxytocin that says, "This person can help me feel better. Everything will be okay." On the other side, when we don't feel successful in that place, our body produces cortisol because it is stressful. The crying is really intense, which overwhelms the caregiver, who often feels they aren't doing things right. This will also produce increased cortisol levels in infants, who say, something's not right, and I don't know why, but I can't get calm.

Thinking about our folks engaged in child welfare when there have been persistent incidents of physical abuse and neglect, the overproduction of cortisol long-term can have neurological implications that we can see. Children have an intense stressed time in infancy and early childhood. They are much less able to tolerate shifts and change and self-regulate. Even as they age, they become much more easily overwhelmed and stressed and much quicker to respond to lower-level stimuli. I refer to this process as the ABA of neurodevelopment. If you do a thing well and connect, you get the oxytocin reward. Your brain says, "Good job." That's the thing you should do. When we're unable to find each other and match, our brain produces cortisol, which often means we don't want to do this and want to fix this as quickly as possible. That back and forth begins to add to that place of rhythm and getting into a routine, finding our own way. The first six weeks of that kind of cue and response helps lay that foundation.

The Crying Curve

In 1991, Barr, Kenner, et al. conducted a study examining infant crying to determine what happens, what it means for babies to be fussy, and how bad it is. The study found that generally, crying peaks in intensity and frequency at about six weeks old and then decreases. That study is usually referred to as the crying curve. Now, while the study found that, generally, crying peaks at six weeks and then decreases, that crying curve looks different for all babies. Even in stable, sustainable, consistent, and predictable caregiving environments, some babies just cry more, and others don't cry as much. While they may also reach their peak at six weeks, they may not have cried as much to begin with, and then also cry even less after that six-week mark. But, pretty consistently, crying increases and peaks at about six weeks and then dissipates from there forward.

The information gained from the crying curve established some containment that the experience of "fussy" crying was, to some extent, predictable and typical. We can say that the first six weeks will be rough, but it'll get better. We can't say how much better or exactly when, but we know it decreases after the first six weeks. That gives some normalcy to this process. The National Center on Shaken Baby Syndrome used this initial information from the crying curve to develop the awareness campaign called PURPLE Crying.

PURPLE Crying

PURPLE is an acronym that stands for:

- PEAK of Crying

- Unexpected

- Resists Soothing

- Pain-Like Face

- Long Lasting

- Evening

We know there will be a peak of crying in the first six weeks, which can often be unanticipated. For example, everything seemed fine, and now they're crying for the next 45 minutes, they're not easily soothed, they appear quite distressed, and it can last a while, more commonly in the evening hours. The Period of PURPLE Crying is a period of time, so the awareness campaign hopes to emphasize that this is a typical early childhood development phase, much like biting. No one loves that, and it's not a fun phase. If you've ever been the caregiver of a kiddo who was a biter, you know we want this phase to be over quickly. It is a typical early childhood development phase that we can name and talk about. We can normalize that this event occurs in early childhood and parenting. When we name a thing, we can contain a thing. It also emphasizes that there's an end. That end may not be today. Tomorrow may only be marginally better. But the reality is that there will be an end.

Pediatric abusive head trauma most often occurs during this intense six-week crying curve of the Period of PURPLE Crying. We discussed this already, but parents often report higher-than-average stress around crying when they perceive their baby to be fussy. Whether that baby's actually crying more or less than other babies does not matter. Parents will report increased stress because they perceive their children to be fussy. Some of this can also come from a parent's background or cultural expectations of whether children should be seen and not heard. Is there an expectation that babies obey even when they're very young? By this kind of excessive perceived crying, what does that say about this baby? Is this baby going to be a problem child? Is this baby going to disrupt life as I expected it?

I have heard parents say, "See, this baby already won't listen to me. How am I supposed to parent them when they get older?" That's pretty common. Perceptions of babies begin before birth and are often connected to parents' experiences as a child and to their thoughts about being a parent. One of the things we often wonder about in this space is, who is this baby, and who is this baby to me? Again, I feel like I should asterisk here before I launch into these stories. Know this is about to be intense content.

I think about families where I saw this play out. One of the families I think about most intensely was a family seeing me for their ninth child. The eight prior had all been removed from child welfare, placed, and adopted in various dynamics. The ninth child, who was seeing me, was currently placed in foster care. The 10th baby was born during that process of services. There were many stories about the 10th baby. One time, they got to the office, brought the baby in a stroller, and I dropped into what we generally refer to as mother ease, that vocal tone you use when talking to babies. I said, "Oh, sweet girl, what's the matter?" Her mom looked at me and said, "Nothin'. She just knows when she's around people she doesn't like." This was a four-month-old baby. The four-month-old baby, I promise, did not have an objection to my personality. Her mother, however, did. This is an example of the perception of how we understand babies and what we understand their cues to be.

Here's another story about that same family. There was one time they were with me when Mom asked for a bottle. Dad pulled the bottle out of the diaper bag, shook it up, looked at it, and said, "I'm pretty sure this has gone sour." Mom said, "Ah, she'll learn to live with it," took the cap off, and fed it to her anyway. This is a moment where there is that question of how we perceive who this baby is and who this baby is to me.

Pediatric abusive head trauma occurs most often in kids under six months old. It is generally connected to a caregiver's sense of being overwhelmed, feeling out of control, and having limited support or skills to navigate these intensive periods of crying. We know that higher risk factors in other situations increase risk factors for pediatric abusive head trauma and that frequently, afterward, parents will say, "I did not know how to make it stop. I did not know what to do."

Facts and Figures

Pediatric abusive head trauma occurs in about 1,300 child abuse cases annually. It is the leading cause of child abuse-related deaths in the US. While on a case-by-case basis, it doesn't often happen, usually at the point that it is recognized, which is part of our conversation today, it is very often fatal. For those kids who survive those traumatic experiences, the associated care, rehabilitative supports, educational supports, and child welfare interventions cost the US about $13.5 billion annually.

Possible Signs and Symptoms of PAHT

Possible signs and symptoms of pediatric abusive head trauma include seizures, difficulty breathing, cerebral swelling, and an infant being unable to lift their head when previously they could. A lot of these symptoms are associated with swelling, both cerebrally and into the spinal cord. Other signs and symptoms include unequal pupils, subdural hematomas, lethargy, and decreased muscle tone. With hematomas, there are times that pediatric abusive head trauma could be associated with stroke.

PAHT and Spinal Injuries

A study from the Cleveland Clinic found that spinal injuries are an often undiagnosed component of pediatric abusive head trauma that likely occurs more often than PAHT itself. Since there's no humane way to test pediatric abusive head trauma, the study took car crash mannequins and looked at the force of impact on the spine and the brain. Of the 131 mannequins in the crash simulations, 96% met the criteria for a spinal injury, while only 22% met pediatric abusive head trauma criteria.

As a clinician, I am now much more curious about my kiddos, who I know were involved in stressful early caregiving experiences. They may not have a diagnosis of pediatric abusive head trauma or even some symptoms, but what is the likelihood of some spinal damage that may result in low muscle tone, frustration, or increased pain response? Because of this study, we know that it's highly possible and likely that roughly cared-for babies may experience neck and spinal injuries before any neurological impact or PAHT.

PAHT and Cerebral Functioning

Animal simulations of pediatric abusive head trauma have highlighted a clear connection between subdural hematomas and oxygen loss that occur during shaking or other abusive interventions. The initial cerebral impact can stop oxygen during shaking or other abusive interactions. Loss of oxygen means long-term damage to cells within the brain, which can result in a lack of weight gain, growth restriction, and ongoing respiratory concerns. It can also cause issues with your frontal cortex, which is cause and effect, working memory, reading comprehension, and other things that come much later down the developmental trajectory.

Long-Term Outcomes

Thinking about the long term, pediatric abusive head trauma can cause learning disabilities, fine and gross motor delays, speech delays, cerebral palsy, seizures, and cognitive impairments. Cerebral palsy is a cluster of symptoms that can be diagnosed from a myriad of onsets. Still, it is possible that an event of pediatric abusive head trauma could result in a cerebral palsy diagnosis.

Cerebral Damage

Our brain has three primary regions that impact our social-emotional functioning: the frontal cortex, which sits at the front of your brain, your limbic system, and your brain stem. The frontal cortex supports cause-and-effect, impulse control, and higher levels of thinking. Damage in this area will result in increased impulsivity, difficulty with self-regulation, and learning difficulties. Our limbic system supports access to words and memory. Damage in this area may result in speech delays or speech loss and concerns with long-term, short-term, and working memory. Our brain stem is responsible for heart rate, blood pressure, and body temperature. Damage to the brain stem is generally life-threatening.

Risk Factors

We've talked a lot about risk factors, including the perception of the "fussy baby." Parental mental health concerns are a huge risk factor. When parents are more stressed, they are more likely to respond aggressively when they don't feel like they can problem-solve. In addition to mental health concerns, substance abuse concerns are a risk factor. Parents recently in recovery will fall into this category of being fairly stressed and unable to access all their coping skills.

Also, factors that contribute to low oxytocin include placement with alternative caregivers, single-parent homes, and fathers/boyfriends/stepfathers in the first six weeks of life. Previously I talked about the oxytocin release that happens at birth. That is a biologically triggered response, meaning if you didn't biologically give birth to this baby, you would not have an immediate oxytocin response. When we look at non-biological caregivers, we know that their oxytocin response comes on at about six weeks of life. Euphoric flooding will occur, but it's just not at the same time because there's not a biological process there. Fathers, boyfriends, and stepfathers often end up being the "aggressor" in the first six weeks of life. For example, we may have a mama out of commission for some complication. We've got a father, boyfriend, or stepfather with their own risk factors. We don't have that biological support online yet to say, "I know you're upset, and you've been crying for 45 minutes, but you're really cute." That will increase that difficulty in single-parent homes or with alternate caregivers.

Poverty, low socioeconomic status, and low education are also risk factors. Domestic violence, another risk factor, is part of a very stressed system in which some level of aggression has become typical for navigating big feelings. That then becomes a risk factor that we're going to use that same kind of dynamic with everybody around us, including the littles.

Another risk factor is prior CPS reports. Most infants and young children with pediatric abusive head trauma are found to have evidence of other forms of maltreatment, such as bruising or broken bones. I often think about young children and finger bruises. Thinking through what you might see, you should not have four oddly spaced bruises on the upper part of your bicep. Broken bones are commonly seen in shaking, and you may see a baby with bones in various healing stages. One of the other significant pieces we think about with that CPS report is story inconsistencies.

A Case Vignette

Here's a case vignette to think through. It is a real story and is a case that I worked on. All names and major indicating features have been changed for HIPAA compliance purposes.

Bella is a 10-month-old who was referred for therapy due to excessive crying, difficulty being consoled, and extreme physical responses when visiting with her biological caregivers. Bella was removed from biological caregivers at 3 1/2 months old after EMTs were notified that Bella had stopped breathing. EMTs found Bella unconscious upon arrival, with excessive bruising to her head and face. EMTs transported her to a large, Level 1 trauma hospital, who later identified several broken bones in various stages of healing, including a femur break, a collarbone break, and a broken arm. Bella is the first child of her parents, who live in an under-resourced rural area. Upon questioning, the biological caregivers reported that Bella had been at home with a younger cousin and that a game system controller had fallen off the coffee table and hit Bella in the head.

Holding that in mind, I invite you to pause for a few moments and consider what risk factors you see. What risk factors might not be named that we might be curious about?

Mandated Reporting

In the Commonwealth of Kentucky, any person who has reason to believe a child is dependent, neglected, or abused must report this to the Cabinet, the state or local police, or the local prosecutor's office. That results in making everyone in the Commonwealth of Kentucky a mandated reporter. It's not one's single burden, but everybody's job to do it. If there is suspicion that abuse or neglect may have occurred, individuals in Kentucky are to notify the Cabinet for Health and Family Services. While we are all mandated reporters, confronting the need to make a call can often be emotionally evocative, especially if it's not something you've done before. The first one is always really hard. After 15 years, I've made a lot of CPS calls. They don't bother me anymore. But, in the beginning, they do as you think about what will happen, if it's the right call, and what comes next.

Your role as a mandated reporter is to state facts. Authorities decide what happens next. Our role as mandated reporters is never to investigate, only to state what we know. Then it is up to the folks on the other end, trained in that, to decide where to go from here. Not all reports result in CPS involvement. An overwhelming majority of reports do not result in the child's removal. Even those reports that are substantiated, most get therapy, maybe rehab, and some supportive options. A child is rarely removed and placed in foster care. When that happens, there has to be substantial evidence that that was the choice to make, usually partly because of the legal burden.

PAHT as Public Health

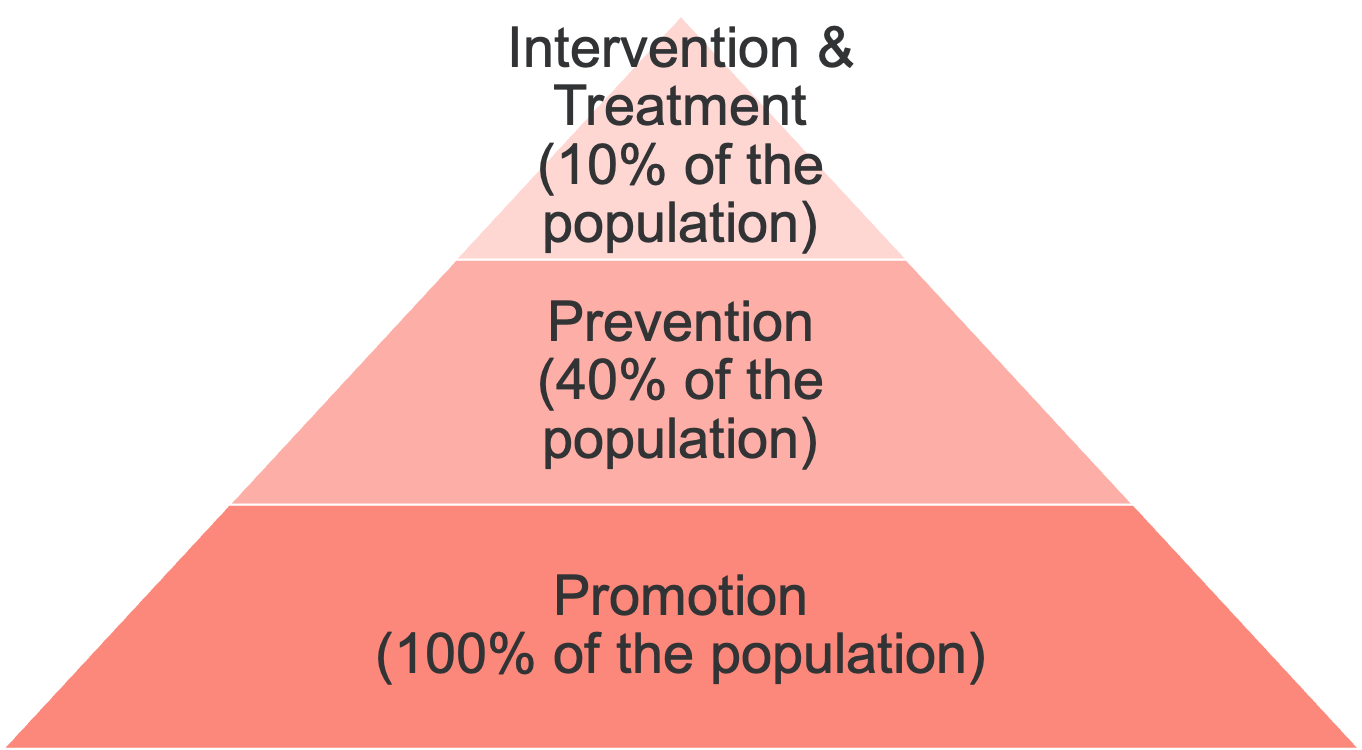

Figure 1. Promotion, prevention, intervention, and treatment of pediatric abusive head trauma.

We've talked a lot about pediatric abusive head trauma and the idea of medical terminology or risk factors or those pieces, but there is also the reality that it is part of public health. When we think about public health models, we're looking for promotion efforts that reach about 100% of the population. Then we look at prevention efforts that reach about 40% of people with higher risk factors and need more intensive support. About 10% of the population will need some intervention and treatment services to address a problem, not just to prevent there from being a problem.

One example of a promotion effort is this course. Another example is that Kentucky must provide some level of education to all high school students. That's 100% of the population. You're getting this information if you go to high school in Kentucky.

Protective Factors

While all families have risk factors, we also want to name that all families have protective factors. When we think about the promotion, prevention, intervention, and treatment levels, we want to leverage the places where families have protective factors and increase parenting capacities to promote positive parenting during challenges. Babies are going to cry, and it's going to be stressful. It will be 2:00 AM at a four-month sleep progression on the weekend of a time change, and those are hard days. Leaning into those protective factors and supporting that place of building positive parenting goes a long way. The protective factors include:

- Knowledge and attachment

- Knowledge of parenting through a developmental lens

- Parental resilience

- Social connections

- Concrete supports for parents

- Social and emotional competence for children

We want to build out nurturing and attachment, knowledge of parenting through a developmental lens, and parental resilience. Often mental health literature presents an expectation that people are born with an internal resilience that will unfold itself magically and that if people are "resilient," they'll figure it out on their own. We know from resilience as a broader topic that resilient people know how to navigate their resources and access what they need. Others may need help building this. Regarding parental resilience, we're talking about those parents who can step away and say, "I've been at this for 45 minutes. My time is up. It is someone else's turn." They can step out, take a deep breath, and come back in.

Social connections mean they're not alone, have somebody to call, and have concrete supports. An example is that the baby goes to Grandma's house every Tuesday. There are predictable, consistent options available to parents. We're building social and emotional competence for children. This begins by thinking through and giving even the smallest babies words like, "You are so upset. Everything feels so big right now. We're going to figure it out together."

Nurturing and attachment include supporting routines, predictability, and shared affect. Shared affect means matching affect. I think about a child we did an observation with a couple of months ago. One of the things we do is ask a parent to leave a room for a brief time so that we can watch the separation and reunion. The caregiver left the room, the child burst into tears, and the caregiver started laughing on the other side of the door. There was a fundamental disconnect in that affect. The child is deeply sad and upset, and the caregiver's affect doesn't match what is expected when seeing the child so upset.

To build the protective factor of parenting and child development knowledge, provide parenting classes and bite-sized, brief information regarding child development and developmentally appropriate behaviors. For example, you may say, "Have you ever heard of PURPLE Crying? Let's check out this website together." Remind parents of developmentally appropriate behaviors and that things like biting happen and are normal. Increase parental resilience, support stress management, frustration tolerance, and flexibility.

Social connections include things like parent cafes. Many states do parent cafes electronically through Zoom so they can be done late at night. Parents don't have to have transportation, and they don't have to leave their houses. There's flexibility, and it doesn't have to be 3:00 PM while getting somebody off the bus. Many churches host moms of preschoolers (MOPs) groups or other support groups.

Concrete supports for parents include WIC offices, Early Head Start, rental assistance, and paid parental leave. I also think about our home visiting sector, including Healthy Families, Nurse-Family Partnership, and Parents as Teachers. There is a variety of home visiting programs. Building social and emotional competence for children includes giving words to feelings and emotions. Becky Bailey's "Conscious Discipline" and the Whole Brained Child can help do this.

Promotions That Work

Let's talk about some promotions, preventions, and interventions that work. A study in Texas conducted from 2017 to 2018 worked with 63 Hispanic mothers to provide education and consultation around infant crying and crying behaviors. The study identified these mothers as Hispanic. Generally, we think about that as Latinx, so I cannot define what they mean by Hispanic. The pre/post tests found that mothers' knowledge and beliefs around infant crying had shifted significantly. Once we talked about it, gave them some education, and normalized it, we saw a change. What is curious about this study is that the pre and post-tests still revealed continued concerns that the information might not apply to their baby. That goes back to the sense of perception of who they are. Am I doing this right? Am I good enough? Is there something wrong? That internal worry, what I often refer to clinically as the heart, can persist even when our head tells us, no, we know differently now.

In Egypt, there was a study of 150 mothers who were given an educational curriculum regarding pediatric abusive head trauma and infant crying. Pre/post-tests were utilized to assess mothers' knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about infant crying. Post-tests revealed improved knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs and improved implementation of the coping skills gained through the curriculum.

In Turkey, a randomized control trial study administered an eight-week course on skills to calm crying babies and build awareness of pediatric abusive head trauma. Post-tests were administered for the intervention and control groups. Results were statistically significantly higher in the intervention group than in the control trial group, meaning that when they compared an intervention with doing nothing, those who got an education could shift their knowledge and awareness.

Synthesizing Findings

When we think about those promotion efforts, we know education matters. When we talk to caregivers about infant and early childhood crying, we normalize what can be a really difficult experience. When we're able to provide skills to families around self-regulation, they're often able to implement those skills and successfully navigate the trying times of parenting. They can recall that education and hold onto it at 2:00 AM when they walk the floor for 45 minutes.

Preventions That Work

In Kentucky, the statewide home visiting program is called Health Access Nurturing Development Services (HANDS). It is funded by the Maternal Infant Early Childhood Home Visiting program (MIECHV), which provides federal dollars to states to provide early prevention services to at-risk families. Those MIECHV-funded opportunities have federal oversight and specific requirements around implementation and fidelity. HANDS supports first-time parents from prenatal to age three for enrollment. They will stay with a family upon enrollment until that child's third birthday. However, there is a requirement that families must face multiple risk factors. There are places in the US that do what's referred to as universal home visiting, which means everybody's got access to it regardless of socioeconomic status or risk factors. But that's pretty rare and doesn't happen often. I encourage you to look up your state's MIECHV and find out what kind of programs they provide. There are 15 or more curriculums that the federal government approves.

Other in-home nursing supports, such as Nurses for Newborns or Nurse-Family Partnerships, are prevention options that support families in prenatal to early infancy. These programs provide additional resources, in-home support, lactation consultants, and increased screening and referrals for post-partum depression or parental mental health needs. It's like having a pediatric medical home for the parents. All of them have really strong outcomes.

Interventions That Work

Look back at figure one, and you'll see the top tier is intervention. This represents ten percent of the children who have had something happen, and now we have to figure out how to repair things that are not going well. This is infant and early childhood mental health in the early childhood sector. This broad-range clinical field takes a psychodynamic perspective. It states that behaviors are rooted in survival and are recognized to have subconscious depth beyond verbal value. Infant and early childhood mental health services are heavily play-based.

Earlier I told you about the family with the four-month-old baby. In that space of rooted-in-survival, it was deeply evocative to watch that mom feed the baby a potentially soured bottle. As a mandated reporter, I had to call that into their DCS worker, but the other piece was that mama had spent many years of her life without food. She had learned that if you've got something, you eat it regardless of whether it's what you want because you don't know where your next meal will come from. Part of her was rooted in thinking; this baby would take what she gets because we may not have another option someday. The infant and early childhood mental health lens will hold that parent's experience and recognize the motivator for behavior while also being able to say, like, "We can't do that."

Interventions in the early childhood sector include child-parent psychotherapy (CPP) and parent-child interaction therapy (PCIT). CPP is evidence-based for kids as young as six weeks old. Infant-parent psychotherapy is what they're calling the perinatal version. That would work even with moms who have yet to give birth. CPP is dyadic, meaning it is caregiver- and child-focused and frequent, meaning it should happen once a week or more. The assessment phase is lengthy, and it takes a long time to get to know everybody and put all the pieces together. CPP is really intentional about its process. It is what we refer to as trauma forward, meaning that we are intentionally addressing potentially traumatic events that may have occurred.

PCIT is an intervention generally used in children two-and-a-half years old through six years old. We may have a kiddo who has had a pediatric abusive head trauma and who's now getting PCIT. That intervention is behaviorally-based, typically focused on compliance, and parent-coaching focused. It is not technically a trauma treatment but should be fairly intensive with weekly sessions. The assessment period is less, and the duration and frequency of sessions vary. Clinicians are highly trained in parent-child work.

Parent-child interaction therapy (PCIT), child-parent psychotherapy (CPP), trauma-based relational intervention (TBRI), Theraplay, and infant-parent psychotherapy are all evidence-based for kids under six years. I want you to know about them. If you're a social worker and a clinician, I encourage you to find some training because there are never enough early childhood clinicians available in any state. As early childhood educators, I encourage you to know that vocabulary to advocate for the families and kiddos you work with. I want you to know that these interventions exist and should be considered. We should be asking about these things.

Regardless of your perspective, there should be caution around any modality with young children that don't heavily involve the caregiver. There should also be caution around heavily talk-based interventions such as CBT for children under five years or where there are language delays. I am always curious how someone can treat an 18-month-old when no caregiver is involved. 18-month-olds are horrible agents of change, so we must rely heavily on caregiver involvement. Play is the language of children. Play is how they tell us about their fears, how they tell us about the wonderful things, and all the space in between. We want to look at their play and consider it pretty intensely.

Summary

Regardless of our professional role, we can offer families the following tips and skills. Take a deep breath and count to 10. Call somebody for emotional support. Many states have fussy baby lines with somebody you can call to walk you through what it is to be in the moment with a really fussy infant. Call a pediatrician. There could be a medical concern. Sometimes babies cry excessively because things hurt, so check it out and make sure that there's not a problem going on. Advise caregivers to leave babies only with trusted caregivers or those who've had a background or reference check.

As we think about the research findings and our promotion, prevention, and intervention sectors, reflect on what caregivers are going through. Considering the study in Texas, is it that parents' concern that something is "wrong" with their baby persists despite education to the contrary? What causes them to think, maybe it is me, perhaps something is wrong with us, or maybe we are not figuring it out? Hold and name that anxiety, and think through some of the skills we talked about that we might be able to share in whatever setting we're in to support caregivers to care best for their fussy babies.

Our Role in PAHT

So what's our role in pediatric abusive head trauma? First of all, our role is to talk about it. A colleague of mine often says, "Lots of things are green, but that doesn't make them all grass." Grass is a thing. The same is true here. PURPLE Crying is a thing. Lots of things can elicit tears, but this really is its own thing. It's important to remember that caring for young babies is difficult and unique for every caregiver. It's a different journey for everybody involved. Know and remind caregivers that services, resources, and supports are available.

Our role is also to report it. If you've observed concerning behavior, interactions, or signs of abuse or neglect, then we are compelled by state mandate to report it. If you're not sure, but you're worried, or something feels off or just not quite right, consult a mentor, leader, or trusted colleague.

Questions and Answers

How is pediatric head trauma diagnosed?

Generally, much like my vignette about Bella, an event occurs that then becomes presented to an ER. We generally see X-rays, CAT scans, and other types of MRIs or imaging. Within that imaging, we're going to see that subdural hematoma. We'll see cerebral swelling and an impact point that may not be obvious externally. We may not have a child who's got a laceration and stitches, but through that imaging, we will see those kinds of symptoms.

Are there any free assessment tools that social workers or early childhood providers can use to assess risk factors for head trauma?

A couple of parental stress indexes are good tools that will give you risk factors across a broad range. They look at everything from socioeconomic status to parents' caregiving dynamic. An inventory called a Life Stressor Checklist (LSC) is helpful for social workers in thinking about what are all the things that a parent comes to this parenting relationship with. It's a thorough history of parents' perception of their baby and what it means to bring it into the world.

Do you have any suggestions for resources for working with parents and families, especially those that are at risk of causing head trauma?

I spoke about the MIECHV program. I'm a huge fan of MIECHV and have had the great privilege of working with them in the Tennessee statewide MIECHV program. Different states disseminate that differently. The evidence-based home visiting sector does such an incredible job. WIC offices are generally fairly well-trained in connecting folks in early prenatal and infancy to local resources. If there's an Early Head Start in your area, I strongly suggest you connect with them. Most states demonstrate Early Head Start as home visiting, not as childcare. That means you'll have somebody going into houses, looking at things, being responsive to phone calls, and connecting with folks in those first three years.

I also am a huge proponent of Part C services under Early Intervention. Even if a child is not terribly developmentally delayed if you think there is any reason that the child might need a developmental assessment, make that Part C referral. Those folks are great to come out. Even when development is on track, they're always offering parenting support groups or options about community-based programs, and they know what's available locally.

References

A complete list of references is available in the course handout.

Citation

Peak, A. (2022). Pediatric abusive head trauma: Recognition, prevention, and long-term impact. Continued Social Work, Article 204. Available from www.continued.com/social-work