Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Person-in-Environment Amplified: Understanding the Role of ACEs in Clinical Conceptualization presented by Alison D. Peak, MSW, LCSW, IMH-E.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Examine the development of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) as a research topic and as a method of understanding the context in which a client develops.

- Identify general research statistics on the impact of ACES on long-term health outcomes and health disparities.

- Consider the use of ACEs in clinical work and its ethical implications.

Introduction

We are going to look at ACEs as a research topic and a method of understanding the context in which clients develop these experiences. We are also going to look at general research statistics regarding the impact of ACEs on long-term health outcomes and disparities. We will then consider the use of ACEs in clinical work and the potential ethical implications for that.

What Are Adverse Childhood Experiences?

I work out of Tennessee, which has been a national leader with information and training regarding ACEs. However, there are other parts of the country that do not emphasize it as much. Some of you may already have some experience in ACEs training and others may see this as a new concept.

ACEs are a series of 10 items that have been found to be directly linked to the following:

- Childhood Development

- Brain Architecture

- Academic Success

- Health Outcomes

- Job Satisfaction

- Divorce Rates

- Life Expectancy

The Story of ACEs

ACEs came to be in the mid to late 1990s by a medical insurance company in California called Kaiser-Permanente. They noticed that there was a portion of their members consuming the majority of their financial resources, as well as the time of their physicians and healthcare providers. These super-users were experiencing multiple complex health presentations. An example of this would be a client having Type 2 diabetes and depression at the same time. These medical concerns were chronic in nature and often consumed a large amount of medical resources and funding of the insurance company.

The company sent out a research questionnaire with hundreds of questions about different experiences in health behaviors: How old were you when you learned to drive a car? What age were you when you started drinking? How many cross-country moves do you have? Have you ever been in a car accident? Genetic backgrounds and experiences were included in this as well. They then found that list of 10 items. If these occurred before the age of 18, this increased people's likelihoods of having long-term health outcomes. They also found that there was a complexity to those experiences that increased medical risk.

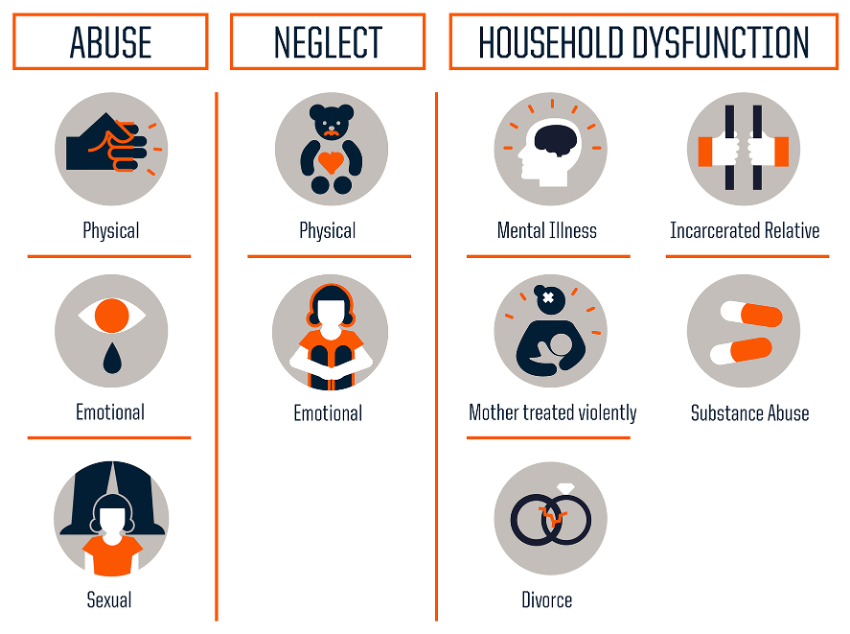

Figure 1. Image of the ten ACEs.

Those 10 key factors break down into two primary subtotals: abuse and neglect. This includes physical, emotional, and sexual abuse and physical and emotional neglect. There is also the realm of family and household dysfunction. There are many questions that can be asked: was there anybody in your home prior to the age of 18 who was diagnosed with a mental illness? Did you have a relative who resided with you and was incarcerated before your 18th birthday? Did you have a parent who experienced substance abuse? Were your parents divorced prior to your 18th birthday? Was someone in your family treated violently prior to your 18th birthday?

This list can be evocative and we need to recognize what this means for us as clinicians. People tend to look at the list of ACEs and begin to evaluate themselves. It is natural to be curious and want to see the world through our own lens. Many clinicians have not experienced these ACEs. However, there is a universality when we talk about early childhood. We have all been young, when our voices were small. We would get frustrated because when we attempted to communicate big emotions and needs, the adults around us did not always hear us. Those relationships are surrounded by rupture and repair. There is universality in ACEs as well because they may hit home with our experiences as young children. It can be an emotional learning experience. Spend this time by thinking about how this applies to clients.

However, the study for ACEs has some shortcomings. One issue is that the idea of domestic violence at the time was that it was perpetrated by a man onto a woman in a heterosexual relationship. The original question was, “Was your mother treated violently?” We now know that intimate partner violence looks different from what we previously assumed. The current question is, “Was anyone in your home treated violently by their significant other or partner?”

How Common Are ACEs?

How often do people experience adversity?

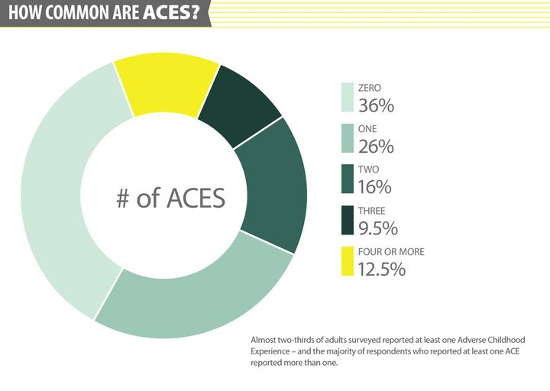

Figure 2. A chart showing the commonalities of ACEs.

The original study showed that 36 percent of those who took the questionnaire had zero ACEs. 26 percent had one ACE and 12.5 percent had four or more. Four ACEs is a cutoff point because research shows that changes start to occur in the body in terms of processing stress and adversity.

ACEs are cumulative and tend to build in risk and experience. The long-term data and health outcomes on one ACE are different from zero, but not statistically significant. When we start looking at compounding two or three ACEs, the data shifts considerably. When there are four or more ACEs, there is data about long-term health outcomes of those individuals.

There were limitations in the original study as well. It was completed on a specific sample size. Do those numbers still hold true when people outside of the specific population are tested? The ACEs study has been completed numerous times on a U.S. state-by-state basis to look at how those numbers apply to smaller localities.

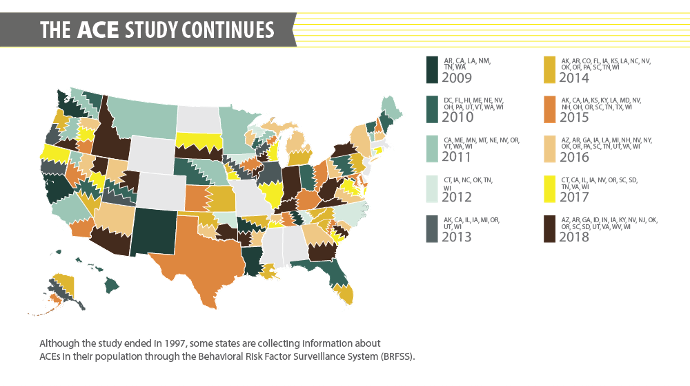

Figure 3. Represents how the study has been conducted nationally.

On this graph, you will notice that some states have repeated the ACEs study numerous times. For example, Tennessee has repeated the study five or six times. We find that when states repeat it over the years, the breakdown remains valid. 12 to 13 percent of the population experiencing four or more ACEs remains consistent.

Research Across the Lifespan

Individuals who have four or more ACEs are at an increased risk for negative, long-term health outcomes. They also have higher rates of cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), depression, anxiety, obesity, high blood pressure, strokes, and so on. For individuals who have six or more ACEs, their average life expectancy is 20 years shorter than someone who has fewer than four ACEs. Statistically speaking, individuals with 10 ACEs become developmentally delayed 100 percent of the time.

When we look at this concept from an insurance standpoint, an ACE score of four or more is estimated to cost about $124 billion to the U.S. economy per person. That number comes from the cost of medical care to those individuals, the lost contribution to the economy, the incarceration for individuals, and the additional government support.

These high scores are correlated to other social determinants. This includes poor job retention, difficulty in graduating college, and divorce. When we have high adversity in early childhood, we have difficulty navigating everything that society has deemed appropriate. This includes being on time and managing tasks. It is also about internal chaos. An example of this is someone being in a job for two years and feeling like they need something new. Individuals with four or more ACEs are also at an increased likelihood of being the parents to children who are involved in the child welfare system. Research shows that ACEs are intergenerational and can be passed down. Many of the effects that ACEs have on our body system often result in having difficulty identifying danger or ways to protect others from danger. That is what creates an intergenerational loop. This can show up through language and verbiage as well.

Understanding the Research

Regarding the shortcomings, the original sample size was predominantly white, middle-class, and mostly had Master's degrees. It was also published in the 1990s, but there was not a lot of conversation about it until 2010 when pediatrician Nadine Burke Harris did a TED Talk about it. She discussed the impact of ACEs and the distribution of public health as a representation of socio-economic injustice and racism. That conversation lit a fire across the nation regarding adversity in early childhood and what that means for our healthcare systems. Through recognizing the limitations in the studies, extreme poverty and incidents of racism have been supported to be ACEs. Extreme poverty is identified as being below the federal poverty line, which can indicate that individuals are on state-based Medicaid.

The questions are left to individual interpretation and what we identify as traumatic is up to the self. Our internalization of those experiences is representative of the way that our body stores those experiences, as well as the damage it does on our physical system. Many of us may not identify an experience as traumatic, but somebody else might. How people identify trauma and adversity in early childhood are reflective of their long-term health outcomes. All ACEs are traumas, but not all traumas are ACEs. This idea is linked to a research perspective that has evidence of impact on physical health. Events are traumatic, but they may not meet the threshold from a research standpoint. For example, our current experiences around COVID are not ACEs. There is no current research to show that living through quarantine has an impact on our long-term health outcomes. When we think about chronic exposure to trauma, the decaying of the body systems is due to wear and tear. This is how ACEs manifest in the body after being exposed to trauma on a daily basis.

ACEs in Early Childhood

ACEs are directly linked to chronic stress, so it is important to remember that not all traumas are ACES. There have been four deadly tornadoes in Tennessee in the last two months. They are not ACEs because ACEs are about chronic trauma, not single-incident trauma. The listed ACEs occur frequently across a period of time. For example, a car accident can be traumatic, but it has a clear beginning and a clear ending.

Constantly feeling the potential for chaos increases the level of chronic stress and exposure to chronic trauma. Chronic stress builds production of cortisol in the brain. This is a hormone that puts us into fight, flight, or freeze. Cortisol is important to have, but we are not supposed to remain in survival mode. When our brain continues to produce cortisol, the brain lowers function in other areas. It pulls the brain’s power back to the places that are going to ensure our survival the most. The parts that control heartbeat, blood pressure, body temperature, and impulse control are referred to as executive functions. From a survival standpoint, the brain is most concerned that we live through an experience. It is not important that we make a good decision during the situation, or that we use kind words. When we are consistently exposed to cortisol, we tend to stay in those parts of our brain for a longer period than normal.

Brain Architecture

We know that positive development and neurological formation during early childhood are foundational through relationships. They teach young children how to regulate themselves, what is safe and what is dangerous, how to ask for help, and how to use other people to effectively meet their own emotional needs. Being in relationships and connecting with others is our greatest survival skill.

Increased chronic stress damages impulse control, analytical thinking, and cause and effect. Children are not good at those things and when their brains are not fully formed, their development is delayed due to chronic exposure to stress. The brain gets stuck in order to make sure that we survive. It is not concerned with progressing from a developmental standpoint.

The anchoring point for experiences of adversity are safe and predictable relationships because they allow kids to do things like social reference. Through looking for security in these relationships, kids can then determine if a situation is safe or dangerous, as well as if there somebody who can help hold their feelings.

Executive Functioning

We often talk about executive functions representing an air traffic control system. It is the tower of the brain that is looking for everything that is incoming and being able to identify what should be navigated. Young children are constantly experiencing big feelings. When we become young adults, there are always questions: did I make the right decision about college? Should I take a gap year? What if people do not like me? Was it a mistake for me to go out with this person? Are my friends mad at me? It is about looming decisions that require air traffic control in order to regulate emotions, take in various sources of information, and modulate our own reactions. This way all of those planes can land safely.

When kids have numerous ACEs, it is often that their control tower is offline. This aspect is a part of the higher levels of incarceration and higher rates of difficulty maintaining a job. Our brain is working so hard to survive that the control tower is not doing its job to prioritize and work through situations.

Intergenerational Transmission of ACEs

Parents who have experienced abuse and neglect are likely to have children who also experience abuse and neglect. There is repetition throughout generations regarding adversity, and some of that comes from parenting in direct contrast to how they were parented. The opposite of unhealthy is just a different version of unhealthy. The middle ground, in dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) language, is where we find healthy parenting and healthy relationships. When parents have experienced ACEs and they either parent as they were parented or parent in direct contrast, we see that children experience repetition with those adversities.

We see this with animals as well. When mice pups are born, the parents engage in two patterns of essentially nursing. One is high arched-back nursing and the other is a dystonic-like, low back nursing. We see higher rates of cortisol in more apathetic nursing. On the other hand, there are higher rates of oxytocin and other positive hormones with high-backed participation nursing. Even when mice pups are switched to a caregiver who acts differently from their biological parent, their DNA will shift. When they become parents, they are able to engage in nursing that directly mimics the way they were nursed as babies. Our DNA holds the experience of how we were given care.

In the 1970s there was a researcher named Selma Fraiberg from the University of Michigan. She was the foundational author for early childhood work and infant mental health. She led a research project known as Ghosts in the Nursery about families dealing with a visual impairment. They did a controlled trial observation which involved a family at a hospital. The mother was 19 years old and as the team observed, the baby started to cry. The mom did not go to the baby or speak to the baby, but instead sat in the room for 20 minutes with a screaming infant. The team stepped back and wondered why the mother could not hear the baby. They began to recognize that there can be subconscious, unknown forces that lurk in the early experiences of parents and children. These forces motivate the way that we engage in and receive caregiving, and they impact long-term experiences of adversity.

Clinical Considerations of ACEs

What does this mean for clinicians? This may be applicable for those of you who work with young children. For those of you who do not work with children, how can this apply to you? ACEs underscore how we develop and are essential in navigating the world and understanding relationships. The duration of that lasts a lifetime. When we learn as young children that adults are unsafe or unhelpful, we hold that internal belief until there is possibility for it to be proven otherwise. Many of the experiences that we see in adults regarding gerontology, including substance abuse or personality disorders, is about asking ourselves if the people around us are safe. What am I doing in the context of relationships to find security and affirmation? Experiences from early childhood connect to the presentation of the problem at hand.

ACEs are cumulative, and we have the ability to provide insight to clients about what it means to have lived their life. It is a good place for us to provide that information to parents and families. I was watching a lecture series called Haruv From the Couch. Alicia Lieberman from the University of California at San Francisco used this lovely analogy of a wave: some people are good swimmers, and a large wave to a surfer is a place of excitement. For those of us who are not strong swimmers, a large wave would be terrifying and potentially lethal. Cumulative experiences of adversity make a difference for what feels dangerous to many of us. A wave from the perspective of a three-year-old looks much bigger than it does to an experienced surfer. It is important to understand the cumulative impact of ACEs that add depth to our client’s narrative. Know that their waves have been back-to-back.

ACEs allow for a grounding point during intake and assessment. This allows clinicians to consider how the client’s experiences are linked to their physical health. For those of us who have experience in medical social work or hospice care, there is always the consideration of the public health’s role in social determinants of health. From a public health standpoint, racism in community planning exposes individuals to higher rates of toxins. Those are moments when we are going to see higher rates of asthma and COPD. They also may be complicated by the adversity that an individual has experienced, as well as the internal stress on their body. Being able to hold those factors together allows us to do a thorough evaluation of the connection between an emotional and physical experience. It can also be helpful in considering linking ACEs as an assessment to an intervention. What is the priority in our clinical decision-making? Is there a current crisis that must be navigated?

The Power of Hope

Remember that ACEs are fact, not fate. Research says that with a score of greater than six, life expectancy is cut by 20 years. Understanding the complexity of ACEs has the opportunity to drive our decision-making and clinically look at how we are preventing and their impact. It also creates resiliency within individuals. That process along with work and positive relationships allow the opportunity for healing.

The largest factor around resiliency is a predictable relationship with an adult. It could be with a parent, guidance counselor, or neighbor. They could be any consistent person who loves the child. This creates a reparative option for chronic stress and trauma. In 2005, Alicia Lieberman worked on a project out of the University of California at San Francisco. She talked to a funder about Ghosts in the Nursery and the work that she did with Selma Fraiberg on intergenerational transmission of trauma. The funder suggested that there are angels as well. This was a turning point after 35 years of working on the subconscious forces that drive decision-making. There are also benevolent experiences that motivate us to go down a different path and help us realize that not all adults are scary.

This theory also states that hope is created when an individual knows they have multiple paths to reach a desired outcome. Even though childhood experiences may not have been positive on most days, there is an opportunity to take an alternative route and achieve that experience in a different way. One of our greatest responsibilities as clinicians is to foster hope and provide evidence for clients that do not have to go the way they have in the past.

Ethical Considerations of ACEs

There are some ethical considerations to keep in mind when we are thinking through the use of ACEs, specifically in the realm of research. It was not intended to be a clinical assessment for people to fill out on their own. Take a moment to think through how evocative that would be for each of you. When I teach at universities and do this presentation, I see people pull out a piece of paper and start making tally marks. We all have the internal need to know where we fit in the greater picture of this. There have been agencies and organizations who, with the best of intentions, give out ACEs screeners as part of intake paperwork. It is not designed to be an assessment tool.

They should always be associated in the context of psychoeducation and what that means for long-term health outcomes. There is solid grounding for ACEs within fact and not fate. People are given hope around their own experience because if they go home and research themselves, the information can be overwhelming.

If somebody uses an ACEs questionnaire, it is imperative that that associated information is shared in that moment so clients do not go find it on their own. That creates internal anxiety within the client because they want to know what is going on with them. It should be about the consideration of whether using an ACEs questionnaire is necessary. If you are doing a thorough biopsychosocial, all of that information should be in a trauma assessment.

There are also limitations. I have seen situations where organizations or individuals use an ACE questionnaire as the trauma assessment. This does not work because there are a lot of things it misses. Examples such as COVID, tornadoes, house fires, car accidents, and the death of a sibling are not ACEs. In that case, it is sufficient to use stand-alone assessments for traumatic experiences. It should be considered whether it is necessary before we provide it. We hold our own research lens that we are modeling, and that information is reflected in that larger, general biopsychosocial.

If you are going to provide an ACEs questionnaire, you should also consider where it is going to be stored. If you complete an ACEs questionnaire for the parents or foster parents of a child, where do those scores go? Does that mean there is another chart opened on those individuals? How do they feel about that? What does that mean for their treatment? If we are considering ACEs for parents, how do we communicate that information to those who may not have a clinical perspective or ACEs training?

We also want to remember that raw data is never to be submitted with a chart for legal review. It is a part of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) that is allowed to be left out when there is a subpoena for a chart. This is because raw data needs to be interpreted. That questionnaire could be sent to a judge who may not have any background in ACEs. They then do their own Googling and come to their own conclusion based on research, not healing.

There is a real consideration around doing any type of screener. What does it mean? Where is it going to be stored? What is the long-term purpose? We gain benefit from this by knowing the information and doing a thorough assessment. Risks include lacking a balance of what we know about outcomes for those with high scores and listening to the experiences of each client. We may know what the research says, but we do not know the narrative. Being able to hold knowledge and space for experience is important. Holding both of those equally can be difficult.

Conclusion

I want to direct you to the slide regarding cultural competence, specifically for the NASW standards. Today we talked about the role of ACEs and diversity, specifically how the original research played into it. The race component involves the white demographic that was originally tested, as well as events of racism being an additional ACE.

Questions and Answers

You spoke about being careful with charting ACEs. Can you speak about the negativity that is associated with that and why practitioners should stray from it?

Social workers should always hold a lens to the social stigma associated with services and the experiences of adversity. We see that within ACEs as well. ACEs are helpful because it presents our internal information about intergenerational trauma in a way that is accessible to those who are not clinicians. Those people can look at ACEs data and compute what it means for their work. It allows people to understand which early childhood experiences play a role in our long-term development. This is why snapshots can be dangerous. They do not capture the full picture and ACEs screeners can walk a fine line with that. We work with the child welfare system for our practice, so we will not release ACEs data. We will also politely decline when courts ask us to facilitate an ACEs screener if they simply want a thorough picture of the family. That social justice lens goes along with the ethical dynamic of giving a voice to the entire experience of a client. You can then make a decision.

References

Brain Architecture. (2014). Palix Foundation/Alberta Family Wellness. Retrieved from https://www.albertafamilywellness.org/resources/video/brain-architecture

Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Walker, J., Whitfield, C. L., Bremner, J. D., Perry, B. D., Dube, S. R., & Giles, W. H. (2014). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. European Archives of Psychiatry Clinical Neuroscience, 56(3), 174–86.

Anda, R. F., Porter, L. E., & Brown, D. W. (2020). Inside the Adverse Childhood Experience Score: Strengths, Limitations, and Misapplications. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 1-3.

Counts, J., Gillam, R., Shabrie, P., & Eggers, K. (2017). Lemonade for Life-A Pilot Study on a Hope-Infused, Trauma-Informed, Approach to Help Families Understand Their Past and Focus on the Future. Children and Youth Services Review, 79, 228-234.

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258.

Larkin H., Felitti, V. J., & Anda, R. F. (2014). Social work and Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Research: implications for practice and health policy. Social Work in Public Health, 29(1), 1-16.

Loudermilk, E., Loudermilk K., Obenauer, J., & Quinn, M. (2018). Impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) on Adult Alcohol Consumption Behaviors. Child Abuse & Neglect, 86, 368-374.

Madison R. Schmidt, Angela J. Narayan, Victoria M. Atzl, Luisa M. Rivera & Alicia F. Lieberman (2020) Childhood Maltreatment on the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Scale versus the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) in a Perinatal Sample, Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 29:1, 38-56, DOI: 10.1080/10926771.2018.1524806

Stein, M.D., Conti, M.T., Kenney, S., et al. (2017). Adverse Childhood Experience Effects on Opioid Use Initiation, Injection Use, and Overdose Among Persons with Opioid Use Disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 179, 325-329.

Spratt, T., Devaney, J., & Frederick, J., (2019). Adverse Childhood Experiences: Beyond Signs of Safety; Reimagining the Organization and Practice of Social Work with Children and Families. British Journal of Social Work

The ACE Study Survey Data. (2016) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Kaiser Permanente. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Topitzes, J., Pate, D. J., Berman, N. D., & Medina-Kirchner, C. (2016). Adverse Childhood Experiences, Health, and Employment: A Study of Men Seeking Job Services. Child Abuse & Neglect, 61, 23-24.

Turney, K. (2018). Adverse Childhood Experiences Among Children of Incarcerated Parents. Children and Youth Services Review, 89, 218-225.

Citation

Peak, A. D. (2024). Person-in-environment amplified: Understanding the role of ACEs in clinical conceptualization. Continued.com, Article 32. Available at www.continued.com/social-work