Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, The Impact of Tech on Development and Academic Readiness, presented by Angie Neal, MS, CCC-SLP.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- State the current recommendations by the American Academy of Pediatrics for screen use in children ages birth through six years and above.

- List key areas of development that are negatively impacted by excessive screen use.

- Describe strategies that help improve negative consequences of excessive screen time.

Introduction

I became interested in the topic of technology and its impact on development, particularly in relation to academics, about seven years ago. The reason for my interest was the increasing number of referrals I received for preschool and kindergarten students. The concerns raised by teachers were not solely related to speech sound production but focused more on academically prepared students to learn and actively participate in a classroom setting alongside their peers.

In particular, teachers expressed significant concerns about social-emotional skills, including social skills and emotional regulation. Being the research enthusiast that I am, I delved into extensive reading to understand the connections between the observed issues and their underlying causes. It has been intriguing to witness the evolution of research in this area, especially in light of the pandemic.

Play... Then and Now

To begin, I would like you to reflect on your own childhood play experiences. Visualize the place where you lived from birth to the age of five. Envision your house, your neighborhood, and your yard. Recollect the rooms where you played and the activities you enjoyed outdoors. Consider the individuals with whom you played and the toys or objects you used.

Take a moment to recollect your play experiences just before or around kindergarten age.

Now, shift your thoughts to the period from first grade through middle school. Ask yourself the same questions. Were you still residing in the same house, or do you need to reimagine the rooms of a different house where you played? Contemplate how the neighborhood may have changed, the individuals you played with during that time, and even the toys or objects you engaged with.

I encourage you to engage in this exercise because it will help you compare children's play experiences today with your own. How does the play children engage in now differ from the play you experienced?

Something's Different

You've probably already noticed this yourself, but something is different. I hear this from teachers repeatedly, and I've experienced it as well. We're witnessing that children struggle to listen when a book is being read. They find it challenging to maintain attention. Moreover, they face difficulties in following simple instructions, like forming a line and getting their backpacks. Additionally, they encounter problems with basic problem-solving and fail to pick up cues from their classmates. For example, if others are putting on backpacks and lining up, they should do the same.

They are also exhibiting more learned helplessness than usual. A teacher friend of mine shared an incident where a student brought her a snack and requested her to open it because he couldn't. The teacher replied, "You have scissors in your desk. You can open it yourself. Give it a try." However, he responded, "I know I have scissors, but can you please open it?" The teacher declined, and as a result, he didn't even attempt to open it. Instead, he threw the snack in the trash. He didn't make any effort.

Furthermore, we're noticing shorter attention spans. Most children become quite bored after about 10 minutes. There's a significant increase in impulsivity. Another teacher informed me that the level of interruption and outbursts during class is the worst they've seen in the past 7 to 10 years. We're also witnessing kids with shorter tempers. In other words, they react more emotionally than ever before. There's also an impact on fine motor development. For instance, a kindergarten teacher mentioned revising their first-day lessons to include basic instructions, such as how to hold a crayon and a pair of scissors. Just last week, a speech-language pathologist (SLP) shared that they are observing an increase in referrals for autism in middle school. This is intriguing because autism is a developmental delay and not something that typically emerges in middle school.

While the pandemic certainly contributes to these challenges, it's important to remember that they existed before the pandemic. They have only intensified, and we are finally witnessing significant impacts in our data. Much of this relates to play and the language skills developed during play.

Language is the Foundation for Reading

Let's delve into the topic of language and its crucial role in reading and writing—our academic skills. So, what exactly are the components of language? While there are some technical terms for them, all you need to understand is that language comprises sounds, such as the "th" sound, words like "phone" or "pin," word combinations like "this is my pin" (as opposed to Yoda's version, "pin is mine"), and meaningful word parts known as morphemes, such as plural "s" or past tense "-ed." How we use language to interact with others is also an essential aspect. I will now explain and illustrate how each component contributes to reading and writing.

Phonology: Sounds of Language

Phonology refers to the sounds of language. Phonological awareness has been found to be closely linked to reading success, even more so than intelligence. It is the strongest single predictor of word reading difficulties.

Semantics: Words/Vocabulary

Semantics means vocabulary. To comprehend a story, children must possess mental imagery or the ability to create mental representations while reading. This process requires them to form visualizations and play out scenes in their minds as they read. To relate this to your own experience, when reading a work of fiction like Outlander or Where The Crawdads Sing, you likely imagine and create mental movies. Children who lack this mental imagery struggle to visualize the events as they read. However, this is a skill we can teach.

Syntax: Word Combinations

Syntax refers to word order. In 2011 and 2012, SAT scores revealed that only 43% of students were proficient in reading comprehension. Interestingly, the difficulty did not lie in their ability to answer questions related to the text but in comprehending the complex syntactic structure of both the questions and the passages. Syntax plays a significant role. To draw a parallel, think about reading syntactically complex books like Game of Thrones or Lord of the Rings. How challenging is it to understand unfamiliar or more formal syntax? It demands extra attention and effort to comprehend the passage.

Morphology: Meaningful Word Parts

Morphology encompasses the meaningful word parts. Approximately 80% of English words consist of multiple morphemes. These include not only plural "s" and past tense "-ed" but also words like "rewritten," which comprises the prefix "re-," the root word "write," and the past participle "n." The word "rewritten" contains three morphemes. Such complex words make up the majority of unfamiliar words we encounter in texts.

Pragmatics: Use of Language

Pragmatics involves understanding different perspectives, such as realizing that someone else may not share your preference for vanilla ice cream. It also includes interpreting figurative language. As teachers, we often underestimate how frequently we employ figurative language. Pragmatics also encompasses the ability to discern important information from unimportant details. For instance, imagine third-grade students studying Christopher Columbus. Instead of focusing on the significance of his discovery of America and the subsequent events, they become fixated on the names of his ships. They miss the big picture and grasp only irrelevant details that do not contribute to the overall understanding.

Pragmatics also involves making inferences and predictions, conveying points of view, providing essential details, and using specific referents. Referring to the issue of referents, think of children who tell a story using pronouns like "he," "she," and "they" without realizing that the listener may not understand whom those pronouns refer to.

Discourse: Narrative Skills

Discourse refers to our narrative skills and our ability to tell stories. Difficulties comprehending and producing narratives can significantly negatively affect students' educational and social achievements. Children struggling with narrative performance may be at risk of developing social and behavioral problems due to their limited ability to interact with others. Take a moment to consider this: when you return home, do you simply share a collection of facts with your spouse, best friend, or others, or do you weave a story about your day? The ability to communicate and share our stories with each other holds significant social impact. Moreover, from an academic standpoint, a majority of fictional texts are centered around storytelling, while social studies essentially consist of a series of narratives.

The Importance of Play

Let's delve into the significance of play. How does play contribute to academic readiness? Play is an incredibly potent tool for skill development, so much so that it can be used as a potential intervention.

Play holds immense power and can be employed as an intervention to bridge academic gaps in children aged three to six. While this primarily pertains to the age range of three to six, play can be utilized, taught, and facilitated as an intervention. Research indicates that there are significantly greater learning gains in literacy, motor skill development, and social-emotional development when children attend schools and childcare centers that incorporate a mix of instruction, free play, and guided play. In contrast, centers or classrooms with limited play opportunities and an emphasis on rote learning exhibit lower learning outcomes. This is particularly relevant as we observe a decline in play-centered environments in schools.

In my state, several districts have discontinued dramatic play centers, insisting on aligning everything with academic goals. In doing so, we unintentionally hinder the development of children. Allow me to share more data on what research tells us about this. A meta-analysis of 26 studies conducted across 18 countries, including disadvantaged communities like Bangladesh, Rwanda, and Ethiopia, revealed that children in centers and classrooms that prioritize play demonstrate significantly greater learning gains in literacy, motor skills, and social-emotional development (Parker & Thomsen, 2019). This finding stands in contrast to the focus on rote learning. All these findings underscore the importance of free play and guided play, as they offer invaluable opportunities for growth. Now, let's explore this further.

Language Learned Through Play

What exactly do we learn and gain through play? As early childhood educators, I don't need to convince you that play is the work of children. However, I'll provide you with more evidence to support the inclusion of play, especially if it is lacking in your curriculum or dramatic play centers. Play encompasses not only language but also gross motor skills, fine motor skills, and sensory development. Think, play, and do.

Through play, we acquire various language skills at different stages. First, there's phonological awareness. Consider the jump rope rhymes and songs we engage in, like "Two little blackbirds sitting on a hill, one named Jack, one named Jill." These types of activities enhance phonological awareness. Similarly, singing "There was a farmer who had a dog, Bingo was his name-o" and gradually omitting letters with each repetition is also a phonological awareness task involving deletion. These activities also address working memory.

Moreover, play facilitates the acquisition of new vocabulary. For instance, when a child who loves dinosaurs interacts with another less knowledgeable child, they learn to differentiate between a tyrannosaurus, a pterodactyl, and a triceratops based on appearance and the descriptive words used. Additionally, play expands the breadth and depth of vocabulary. If a child knows the word "ball," they will likely be familiar with related words such as "bounce," "round," "roll," "throw," and "kick." Through play, we broaden the range of vocabulary.

When it comes to syntax, think about activities that include role play based on a book or story that we've read. For example, if we read Richard Scarry's "A Day at the Fire Station," the syntax used in play could include sentences like, "Don't park your paint truck in front of the firehouse doors. We firefighters have to be able to drive out at any time." Children practice and extend their understanding of language structure by incorporating language and syntax from the book into their play.

The same applies to schema, which is essentially a term for background knowledge. This background knowledge is acquired through dramatic play and the books you read, such as those about castles or the post office. Let's imagine you have a dramatic play center dedicated to the post office, vet, or zoo. Engaging in these different dramatic play activities enhances your background knowledge. Morphology, on the other hand, involves understanding verb tenses like "I ate the cake" or "I walked" and future tense constructions such as "I'm going to wash the dishes."

Narratives refer to the ability to tell and retell stories. Additionally, in pretend play, like with the dinosaurs I mentioned earlier, children learn how to classify, compare, reason, and understand. This is where the magic of play happens—where the brain begins to develop skills for understanding, sorting, and classifying. Think of it as setting up file cabinets in their heads. When we categorize information in specific files, it becomes easier to remember. For instance, imagine you have a recipe book in a three-ring binder.

What if you wanted to find a recipe for "death by chocolate"? You would go directly to the tab or file labeled "desserts," making it effortless to locate. However, if you accidentally dropped your recipe book and put everything back in without organizing it, finding that recipe would become much more challenging without the files or tabs.

In terms of early childhood, one of my favorite play activities has always been what I call "toy box turnover." It involves enlisting children's help in cleaning out the toy box. All you need to do is ask them to sort and organize the different items in the box.

They can sort them based on color or category—for example, separating animals, transportation, pets, round objects, or red items. Children love this activity. It teaches numbers, quantity, and counting skills and concepts like first, next, last, some, all, and few. They also learn prepositions such as beside, behind, next to, across, top, and bottom. Moreover, they gain an understanding of time concepts like before, after, now, soon, and later.

Additionally, play helps children develop skills such as following directions, both from adults and their peers. Most importantly, it fosters social interaction, teaching children how to share, negotiate, resolve conflicts, make decisions (especially in group settings), cooperate with others, problem-solve, maintain focused attention, and understand others' perspectives. These diverse skills are all nurtured through play.

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, play is fundamentally important because it cultivates problem-solving abilities, collaboration, and creativity, ultimately contributing to the development of executive function.

Executive Function (EF) Learned Through Play

Now, let's delve into what executive function is and why it holds such importance. Executive function, in essence, refers to a collection of mental skills that we employ on a daily basis. These skills enable us to learn, work, and manage our everyday lives effectively. They are utilized consistently throughout the day. To illustrate this, consider the analogy of driving a car. Without executive function skills, driving would be impossible. Consequently, lacking these skills poses challenges in focusing, following instructions, managing emotions, and various other tasks.

This brings us back to the context of students. As mentioned earlier, teaching a teenager to drive can shed light on the difficulty of the process until it becomes second nature. The reason behind this difficulty lies in the fact that driving necessitates constant multitasking. You must plan the route, gauge travel time, and continuously monitor the surroundings, making decisions like whether to stop or proceed at a yellow light. Executive function acts as the conductor orchestrating all these actions. Notably, there is a significant surge in the development of executive function skills during early childhood, specifically between the ages of three and five. However, these skills do not fully mature until around the age of 25. This is one of the reasons why the legal driving age is typically set at 16, as it is around this time that individuals begin to possess executive function skills close to maturity. Moreover, children deeply engaged in play foster the growth of executive function skills, which contributes to their readiness for school.

Now, let's explore the components of executive function. It consists of three interrelated skills. To understand their interconnections, consider the framework provided by the National Early Literacy Panel and the National Education Goals Panel, which informs state standards across the country. When you look at each of those indicators within those domains, you will notice that executive function is listed in every domain.

- Approaches to Play and Learning

- Executive function, emotional regulation, temperament

- Health and Physical Development

- Executive function, visual-spatial skills, precision in movement

- Cognitive Development

- Executive function, number identification, subitizing, ordinality

- Social-Emotional Development

- Executive function

- Language and Literacy

- Executive function, vocabulary, phoneme isolation, letter naming

Three Components of Executive Function

Having discussed the significance of executive function in all areas of learning, let's now delve into its three main components: cognitive flexibility, working memory, and inhibitory control.

Cognitive flexibility lies at the core of problem-solving and perspective-taking. It involves the ability to think about things from different angles. For instance, if children attempt to solve a puzzle and give up after trying just one approach, they lack cognitive flexibility. This skill is primarily acquired through modeling and our own self-talk as adults.

For example, in a classroom situation, you might say out loud, there will be a fire drill in 15 minutes. We will back up recess until after science. Children will learn problem-solving through this type of modeling from adults. On the other hand, perspective-taking is primarily developed through interactive play with other human beings. It's important to emphasize the role of human interaction in fostering this aspect of executive function.

The next component is working memory, which is crucial for multitasking. Working memory can be likened to a mental chalkboard where various items are written, allowing for the manipulation and organization of those pieces. For example, imagine having to run multiple errands after school, such as going to the bank, stopping by Hobby Lobby, and buying milk at the grocery store. Despite the proximity of the grocery store, you would likely prioritize going there last if it's a hot day. This decision-making process and the ability to rearrange tasks based on their importance is an example of using working memory.

The last one is inhibitory control. This is the heart of social-emotional development, particularly inhibiting emotion when you need to and shifting emotion when you need to. Essentially shifting from maybe you're in a really positive state to a neutral state, or you're in a really sad or mad state, and you need to shift into a more neutral state. Inhibitory control plays a pivotal role in social-emotional development. It involves restraining or shifting emotions when necessary. This includes moving from a highly positive or negative emotional state to a more neutral one. Inhibitory control also encompasses the ability to ignore distractions. Consider the phrase "ready, fire, aim." That impulsive approach is counterproductive; ideally, we should aim first before firing. However, many children tend to act first, then aim, lacking inhibitory control. It also involves the capacity to ignore distractions. For instance, imagine waking up late, rushing to work, spilling coffee on yourself while refueling, receiving a speeding ticket just outside the school, and realizing you're wearing mismatched shoes. Your first meeting of the day is an important IEP meeting. From a personal perspective, controlling emotions in a meeting under such circumstances would require considerable effort. This exemplifies the essence of emotional control.

Let's consider a scenario where a student has experienced an emotional outburst, briefly leaving the classroom before returning while still seething with anger. How receptive will they be to learning about Christopher Columbus in this state? Put yourself in a similar emotional state to grasp the impact. It would be unrealistic to expect them to effectively engage in activities such as multiplication tables.

To clarify, executive function skills are not innate; rather, children possess the potential to develop them. They acquire these skills through their environment and the adults who surround them.

Social-Emotional Learning (SEL)

For individuals growing up in adverse environments, it can directly affect the brain's architecture necessary for developing executive function skills. I will explain this further shortly. However, I would like to emphasize the crucial role of the social-emotional component, inhibitory control, and their overlap.

Let's consider social-emotional skills and examine some data. Even as early as kindergarten, children who are classified as challenging to manage at the age of four are more likely than their peers to engage in rule violations and perseverative errors at the age of seven. Perseverative errors refer to instances where they continue to engage in behaviors they know are prohibited, like persistently throwing rocks.

Academic factors, such as language proficiency in relation to reading acquisition, have also been shown to predict behavioral issues by the end of elementary school. These behavior problems can disrupt academic engagement, leading to difficulties in mastering certain skills. For instance, you may have encountered a smart child with an emotional disability classification who struggles with reading. One of the reasons behind their reading difficulties is the amount of time they spent outside the classroom in kindergarten, first grade, and second grade due to behavioral challenges. These associations are likely the reason why behavior in third grade correlates with reading and math proficiency in eighth grade. Significant links exist between social-emotional skills observed in kindergarten and later outcomes in adulthood, including educational attainment, employment, criminal activity, substance abuse, and mental health.

As you may have noticed, there has been a rise in programs specifically targeting social-emotional learning (SEL). These programs acknowledge the impact of social-emotional skills on academic readiness. They focus on inhibitory control, addressing impulsive behaviors, and promoting emotional awareness, labeling, and regulation. Perspective-taking, problem-solving, and conflict resolution are also emphasized in these SEL programs. As you can see, these objectives align closely with the development of executive function skills, highlighting the overlap between SEL and executive function.

Overlap of Social-Emotional Learning and Executive Function

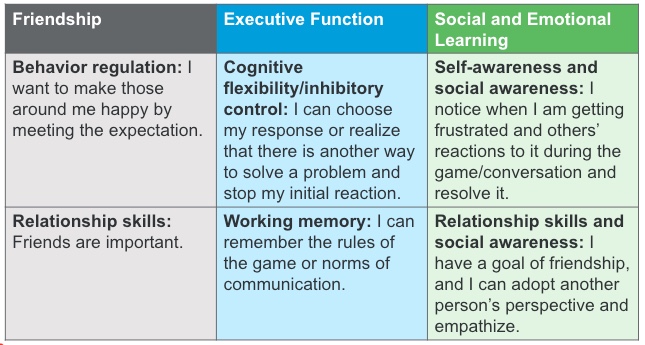

Figure 1. Overlap of social-emotional learning and executive function.

A great example of the intersection between social-emotional learning and executive function is friendship. To establish a friendship with a peer, children need to be aware of how they interact with others. We've all witnessed situations where a friend doesn't get the blue game piece. How do they react? Do they become frustrated and act out? And how do their peers respond to this frustration? Moreover, are children equipped to handle this kind of frustration and adapt by accepting a different game piece, such as the green one?

These social-emotional situations require the use of executive function skills. They involve cognitive flexibility, enabling children to accept not getting the blue piece and considering alternative solutions. Decision-making comes into play as they choose how to respond and problem-solve, such as asking a friend to trade game pieces. They must also be aware that their friends may not want to trade if they act out in frustration, highlighting the need to inhibit their emotions—an executive function skill.

Working memory is crucial as children need to remember game rules, taking turns, and selecting game pieces. These skills are essential for being ready and available to learn. Additional executive function skills involved include the following:

- Perspective taking

- Problem-solving

- Thinking about a problem in multiple ways

- Identifying the problem

- Remembering information

- Storing information for quick retrieval

- Self-monitoring

- Completing multiple steps or applying multiple skills at one time (*writing)

- Controlling impulses

- Paying attention

- Ignoring distractions

- Regulating emotions

- Planning

- Time management

In live presentations, I enjoy engaging adults in playing games like Operation, UNO, Go Fish, and Candy Land for about 30 minutes. I prompt them to reflect on the experience and consider aspects such as waiting their turn, exercising emotional control, and tuning out distractions. These examples illustrate the importance of impulse control during play. Multitasking is also evident in games like Go Fish, where players must remember who asked for a specific card and utilize working memory to maintain focus. Remembering game rules, such as in UNO, and monitoring other players' actions to call out UNO further emphasize the role of working memory.

Problem-solving is another executive function skill required during gameplay. Players must strategize to win, consider others' perspectives, and make judgments about the judge's preferences in games like Apples to Apples. Additionally, in games like UNO, they need to observe nonverbal cues from other players to predict their moves and plan their own actions accordingly. These skills, including perspective-taking and problem-solving, are developed through play.

Overall, the overlapping nature of social-emotional learning and executive function is evident in playing games. All of these skills are developed through play.

Impact of the Pandemic

Let's look at how play, executive function, and language have been impacted by the pandemic. There are two primary reasons for the changes we observe. The first, as you may have guessed, is the pandemic itself. The second reason is the increased screen time among children. Allow me to elaborate on this further. An incredible and fascinating study called the LENA Project, which utilizes advanced technology, is a more tech-savvy version of the Hart and Risley study from 1995. The Hart and Risley study highlighted a 32 million word gap between children from low socioeconomic backgrounds and their peers, emphasizing the relationship between the number of words children hear during language interactions and their academic success.

The LENA Project takes recordings of children and their interactions, capturing the number of words spoken and the frequency of conversational turns with adults. The findings from this project reveal a decline in vocalization and verbalization by children, as well as a decrease in conversational exchanges between adults and children. The impact of these changes is devastating. The trends resulting from this data show a significant drop, nearly one standard deviation, in cognitive development, language development, and nonverbal skills related to visual and motor processing.

To determine these changes, the researchers employed the Mullens, similar to a full-scale IQ test, measuring verbal and nonverbal IQ. The data collected since 2010 demonstrates that children's scores were around 100 before the pandemic, with a standard deviation of 15. However, starting in 2021 and 2022, there was an average decrease of 24.6 points across cognition, verbal, and nonverbal domains for three-year-olds, representing those born during the pandemic.

For children who were one year old during the pandemic and are now four, the decline is even more pronounced, particularly in language skills, with a three-standard-deviation drop and an almost 100-point decrease across cognition and language, both verbal and nonverbal domains. These findings represent the lowest scores observed since data collection began.

Ultimately, these changes can be attributed to conversational turn-taking, as the number of conversational turns per hour significantly impacts brain development. Let me elaborate on this point. Although I will avoid delving too deeply into neuroscience, it is essential to recognize that interaction is the driving force behind development. In other words, talking with children, and not to children, is what drives brain development. Engaging in back-and-forth interactions with adults, whether they are parents or teachers, is one of the most powerful ways to establish a foundation for healthy brain architecture.

An 18-month study examining language development in relation to the impact of adult words, TV exposure, and conversational turn-taking revealed that conversation had the most significant impact on language skills (Deoni, 2021). Verbal language scores increased by one point for every conversational turn per hour, meaning that children who participated in at least 40 conversational turns per hour displayed full-scale IQ scores of 31 percentile points, or 12.9 standard score points, higher than those with fewer conversational turns. Their language scores were 38% higher, equivalent to 16.6 standard score points. Conversely, approximately 6% of children did not experience 40 or more conversational turns per hour.

To put this into perspective, consider a fun experiment. The next time you're with your friends or on the phone, keep a tally of how many times you say something and receive a response. Each exchange counts as one conversational turn, and you'll be surprised by how quickly they add up. Achieving 40 conversational turns per hour is easily attainable within 10 or 15 minutes. This reinforces the importance of not just talking to children but engaging in conversations with them. The quality of interaction and engagement is key.

The Importance of Conversation

Why is conversational turn-taking so important? Let me explain the three significant reasons. First and foremost, children need to be exposed to approximately 20,000 words per day or engage in about 40 conversational turns per hour. This is because, as we learned from the Hart and Risley study, conversations and the vocabulary gained from them are the most influential factors in a child's preschool vocabulary. When children have fewer conversations and, consequently, hear fewer familiar or unfamiliar words, they face difficulties when they encounter new words at school. They don't recognize that they haven't heard those words before and lack the knowledge to ask, "What does that word mean?" This lack of vocabulary knowledge affects their listening comprehension and, in turn, impacts their reading comprehension. They may end up skipping over unfamiliar words, further hindering their reading comprehension abilities.

The second reason why conversation is crucial is for phonological long-term memory. Children who engage in more conversations with adults develop the brain architecture necessary for language and are associated with enhanced reading proficiency. Specifically, a significant aspect of language called phonological long-term memory plays a vital role.

To explain it clearly, let me demonstrate. When a young child is reading, they rely on their pronunciation of words and their knowledge of the word's meaning from their oral vocabulary to recognize words in print. When they decode a word like "suspicious," they recognize it because they have heard it before. This is phonological long-term memory—recalling a word from previous encounters. However, if a word is not part of their oral vocabulary, let's say a complex word like "antidisestablishmentarianism," they will struggle to recognize it in print, even if they decode it accurately. Here are examples to illustrate this point.

Grinch

What do you hear in your mind using your phonological long-term memory when you see that word? You have likely stored that word in your phonological long-term memory, and you may be singing the song from the movie How the Grinch Stole Christmas. When you see the word Grinch, you also likely have that image associated with it. I mentioned the importance of visual imagery. You may think about that green fuzzy big bellied guy who's unpleasant, lives in a mountain cave above Whoville, and puts a reindeer antler on top of his dog, Max. It is a very clear visual image. Consequently, the next time you see that word, you will recognize it more quickly and automatically read it. It is not a sight word per se, but it is nearly instantaneous recognition when reading.

Neurasthenic

What do you hear when you see this word? Probably nothing unless you have heard the word before. As a result, you have to decode it chunk by chunk. You have to flex the vowels and play around with the syllable stress. You may rehearse the word with the stress on the various syllables; you don't know which is correct because it is not stored in your phonological long-term memory.

When words are not heard in conversation, they are not learned and not stored in phonological long-term memory for later use in reading.

The final reason that conversation is so important is referred to as the Matthew effect.

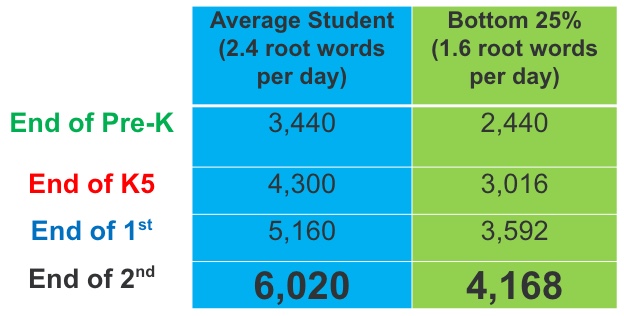

Figure 2. Chart showing The Matthew Effect.

The Matthew Effect

Figure 2 shows that by the end of pre-K, the average student gains about 2.4 root words per day, which amounts to approximately 3,440 new words per year. That's the average child. Now, let's consider a child who started with a vocabulary deficit—those in the bottom 25%. They don't begin with the same number of words and, consequently, don't end up with the same number. In fact, they have about a thousand words less than their peers. This deficit grows to almost 2,000 words by the end of second grade unless we provide explicit instruction. The question is: are we doing that? And if so, how well? Furthermore, what does the data actually say? However, even before pre-K, the research tells us that vocabulary at age three significantly impacts language and reading skills at ages 9 and 10, and it strongly predicts high school graduation.

As someone working in early childhood education, you have the power to make a substantial difference, particularly in terms of vocabulary development. I'm not sure what assessment tool you use for entry into kindergarten, but in our state, we use the kindergarten readiness assessment, which is why that data is crucial. Often, the data from this assessment doesn't provide us with information to influence our instruction directly. However, the kindergarten readiness assessment data aims to help us understand what happened before children entered school and identify any trends. This is crucial because, once again, children who start behind tend to stay behind unless we change our approach.

The last point I want to emphasize is regarding vocabulary, and it draws from the Hart and Risley study. While their research initially focused on low socioeconomic status (SES) children, the importance of a language-rich environment is now applicable across all socioeconomic backgrounds. In other words, even children from middle or upper-class households may not engage in language-rich conversations if they or their parents are preoccupied with technology devices. Consequently, when words go unheard, concepts go unlearned.

Impact of Screen Time and Tech Toys

Let's discuss the impact of technology on children, particularly in relation to toys. It is important to consider the toys you buy and use in your classroom, as research indicates that traditional toys play a crucial role in children's development.

When it comes to technology-related toys, there is negative data regarding conversational turn-taking. Electronic toys with various features, like a cow that makes mooing noises when placed in a barn, have been found to decrease the quantity and quality of language output compared to traditional toys. Adults don't engage in conversation as much if a toy does all the talking or counting for a child. Therefore, it's important to think about the impact of these tech toys on language and literacy development, which should not rely solely on electronic toys.

Tech toys lead to fewer words used by adults, fewer conversational turns, reduced parent responses and engagement, and less production of content-specific words during play. For example, a toy cow with technology won't point out its features like having spots or an udder. It will not make associations with real-life experiences as parents will, for example, "Remember we saw cows near Nana's house." Moreover, when a toy says "moo" on behalf of the child, the child doesn't need to say it themselves. Even before the pandemic, studies started collecting data showing the effects of technology use on young children.

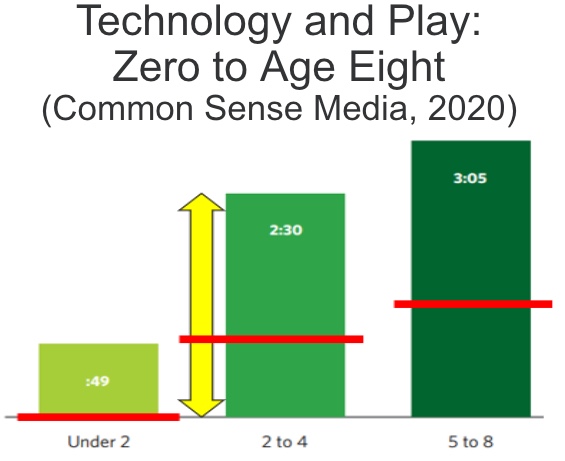

Figure 3. Technology and play: zero to age eight (Common Sense Media, 2022).

The data reveals that two-year-olds in the United States spend less than an hour daily on screens. Two to four-year-olds average about 2.5 hours, and five to eight-year-olds spend a little over three hours on screens. Remember, early brain development is crucial for setting up the architecture of learning. The data shows a threefold increase in screen time from 12 months to 3 years of age, as indicated by the yellow line on the graph.

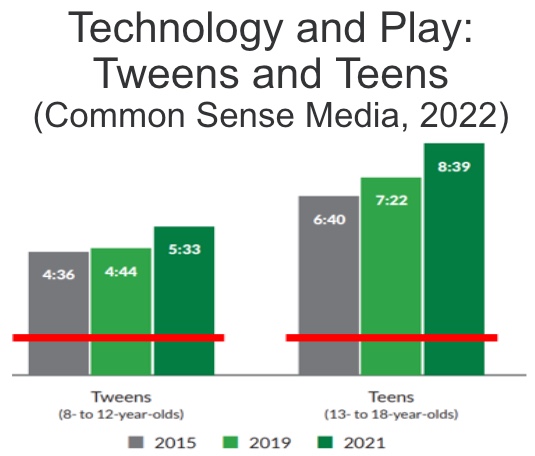

Figure 4. Technology and play: tweens and teens (Common Sense Media, 2022).

For children aged eight and above, tweens spend around 215 to 219 minutes on media use, while teens spend 11% more. Between 2019 and 2021, media use increased by 17% for tweens and teens. On average, 8 to 12-year-olds now use around five and a half hours of screen time daily, and 13 to 18-year-olds spend about 18 and a half hours on screens. The increase in screen time during the pandemic era was greater than the increase across the previous four years. These numbers represent passive screen time, not including schoolwork on a Chromebook or other device.

American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Recommendations

It's essential to consider the recommendations of the American Academy of Pediatrics, the trusted authority on children's health. Like we rely on them for vaccine schedules, car seat guidelines, and medical advice, they provide children's screen time recommendations. The red lines on the graph represent the AAP's guidelines. Here's a summary:

- Under the age of two, no screen time except for interactive video chats (e.g., with family members who are away from home).

- Aged two to five, no more than one hour of screen time per day.

- Five to eight-year-olds, no more than one to one and a half hours per day.

- For children six and older, the AAP shifted from specific time limits to promoting healthy habits and limiting screen activities. They encourage avoiding screens during meals, in the car, and when out and about. It's crucial to prioritize meaningful language and experiences during those times.

- Parents can use parental controls, limit device usage, switch screens to grayscale, avoid using screens as pacifiers, and turn them off before bedtime. We had a student whose difficulties at school were related to screen time. He was being put to bed with a screen and wasn't falling asleep until 2 or 3 AM.

Play and Critical Periods of Development

Let's discuss the importance of these critical years and how they contribute to brain development. During the first three years of life, we must consider how we shape the brain for learning. Infants and toddlers form approximately 1 million neural connections per second between the ages of one and three. It's no wonder they require naps during this time. This highlights the critical importance of these years in building a brain ready for learning. Play is instrumental in facilitating typical brain development. However, when technology is a replacement for play with other humans, it becomes an obstacle for typical brain development in three key areas: dopamine, myelin, and the prefrontal cortex.

Dopamine

Dopamine plays a crucial role in various brain functions, such as behavior, motor activity, motivation, rewards, humor, anxiety, attention, and learning. It is the feel-good chemical released when individuals engage in certain activities, like taking drugs or receiving positive feedback on social media. When external stimuli trigger a release of dopamine, it signals a pleasurable experience, encouraging individuals to seek more of it. Screens have been found to trigger excessive dopamine release, surpassing what our brains are designed for. This flood of dopamine wears down the pathways, leading to a higher demand for stimulation. Technology provides a shortcut to these reward processes, flooding the brain with dopamine without serving any biological function. Kids receive multiple dopamine hits per game or swipe, which becomes an overwhelming flood when combined with the time spent on devices. Humans have not adapted to handle this excessive amount of dopamine, especially before the brain fully develops. The brain craves more dopamine while naturally producing less, making it harder to find joy in everyday experiences. Consequently, screen time becomes addictive as kids seek the dopamine rush.

Furthermore, technology, especially apps and games designed for children, incentivizes play by providing rewards, tokens, or desired objects upon reaching certain levels. It also incorporates random rewards, initially delivering rewards consistently but gradually reducing the reward rate. Screens can also impose punishments, such as withholding rewards if the child stops playing or breaks a streak. When children are forced to stop using screens, their dopamine levels abruptly drop. Young children, who lack the emotional regulation skills developed through interactive play, struggle with this transition, often resulting in tantrums or resistance. In fact, 93% of parents report that their children occasionally throw tantrums, whine, or resist ending screen time. This widespread response highlights the issue at hand.

Myelin

Now, let's discuss myelin. Myelin, also known as white matter, is composed of a high lipid fat that coats the brain's neural pathways. Brain cells responsible for producing the protein, fat, lipid, and cholesterol needed for myelination are fragile and easily damaged by various factors, including head trauma, stress, toxins, drugs, excessive stimulation, and overstimulation. When children experience an overload of stimulation or the wrong type of stimulation, it hinders efficient brain development required for learning new words, comprehending complex sentences, focusing attention, and engaging in play with others. Overstimulation restricts synaptic growth and inhibits the creation of myelin necessary for utilizing existing knowledge effectively. At three months old, the brain is merely a gray mass, but around 8 to 12 months, myelination becomes visible in brain scans. By 24 months, the brain triples in size, a remarkable growth that only occurs during this critical period. Consequently, the brain is 85% complete by age three, emphasizing the significance of early childhood experiences, such as play. The LENA project found a significant association between the rate of myelination and the number of conversational terms per hour. It's not just the words heard but the meaningful interactions and experience that matters.

Synapses only form based on meaningful experiences, not repetitive actions on an app. To better explain myelination, let's use an analogy. Imagine a cord with multiple other cords inside. Myelin is like the protective outer coating of all those cords. If the cords are exposed, like when a phone charger starts to separate, the cord doesn't work as well. But the information and energy flow smoothly when there's a protective coating. That's what myelin does—it acts as the outer layer, facilitating efficient communication.

When children are young, it is as if we prune synapses to make them more refined and efficient, allowing for faster processing. It's similar to toddlers learning to walk—they start off hilariously clumsy but become more efficient over time. This principle applies to reading outcomes as well. The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) found that children aged three to five who engage in less play and exceed the recommended screen time (no more than one hour a day, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics) have less myelination supporting language and emergent literacy skills and corresponding cognitive assessments (JAMA, 2020).

In other words, there is indeed an impact on brain development. Although the brain has the capacity to change and learn at any age due to its plasticity, it's most efficient during the first five years. This is because early childhood experiences, such as play, shape healthy brain development. It's much harder for children to catch up if they start behind. To illustrate this, I often use the comparison of mental junk food. The content children consume on screens is essentially mental junk food—it doesn't contribute to or promote healthy brain development. If you wouldn't give your child a steady diet of Cheetos, french fries, and Oreos, why would you expose them to a constant stream of mental junk food? This analogy can help parents understand the importance of prioritizing meaningful experiences over excessive screen time in a way that makes sense.

Prefrontal Cortex

Now, let's discuss the prefrontal cortex as it relates to play, language, and executive function. Executive function is located in the prefrontal cortex and is responsible for regulating impulsiveness, emotionality, and aggression. If you've ever encountered someone with a frontal lobe injury, you'll have observed the effects firsthand.

Over time, researchers have conducted a captivating study on this subject. The National Institute of Health is undertaking a $300 million study called the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development℠ Study (ABCD Study®) that employs MRIs to capture images of the brain and monitor structural changes in children who use smartphones and handheld screens. So far, they have examined 4,500 children aged 9 to 10, and this study will continue for a period of 10 years.

The initial results from 2018 revealed that children who spend more than two hours a day on screens—just two hours—tend to score lower on language and cognition tests. Moreover, children who spend seven or more hours a day on screens exhibit premature thinning of the cortex, a phenomenon typically associated with conditions like Alzheimer's or Parkinson's disease. These findings carry significant implications.

Not Just Children

Let us also acknowledge that there is an impact when parents are engrossed in their screens. In other words, the effects are equally significant when someone is close to a child but uses a screen instead of engaging in conversation, taking turns, or playing with them. The data shows that 95% of parents report that technology interferes with their daily opportunities to talk, play, and interact with their children without distractions, at least to some extent. This is a clear indication of the problem.

One of the major reasons behind this issue is what's known as continuous partial attention. Continuous partial attention disrupts our most primitive and basic emotional queuing system, which relies on responsive communication. When someone notices you're sad, they comfort you. When someone sees you laughing, they respond with a smile. This emotional queuing system is affected by continuous partial attention.

An intriguing study conducted by Temple University (Radesky et al., 2015) examined the impact of parental cell phone use on language development. They had mothers and two-year-olds enter a room, and the mothers were instructed to teach the child two new words. They were provided a phone so investigators could contact them from another room. Whenever the mothers were interrupted by a call, the children did not learn the words—neither of them. However, when the mothers were not interrupted, the children did learn the two new words. This study supports the idea that there are times when parents need a few minutes for themselves, such as when they need to take a shower, cook, or have a conversation with another adult, including their spouse.

During these moments, it's beneficial for children to engage in independent activities, but not through screen time. This promotes their independence, gives them an opportunity to experience boredom (a long-lost art), and encourages play. Now, here's a critical aspect of continuous partial attention to consider: when parents are physically present with their child, let's say in the same room or playroom, but fail to pay attention to them, it sends a message that the child is less valuable than whatever is on the phone. Perhaps you've experienced this scenario while dining at a restaurant with someone who gets absorbed in their phone—how does it make you feel? This combination of physical presence and emotional disconnection is detrimental to our students and children. Therefore, when parents are preoccupied with screens, there is a decrease in verbal interactions and conversational turn-taking, all of which have an impact on the child.

Screen Time - Autism

Now let's discuss the impact of screen time on autism. This is fascinating data from Dong et al. (2021). There is a positive correlation between screen time and CARS scores. CARS stands for Childhood Autism Rating Scale. The more time a child spends on screens, the more obvious the autistic-like symptoms. This is because increased screen time means less time for play, limited engagement in conversation affecting social language development, and reduced social interaction with others. However, it's crucial to emphasize that technology does not cause autism. Instead, the disproportionate exposure during critical periods of development for learning to play, interact, develop executive function, and acquire language skills impacts the development of social communication and social-emotional skills, resembling autism-like behaviors.

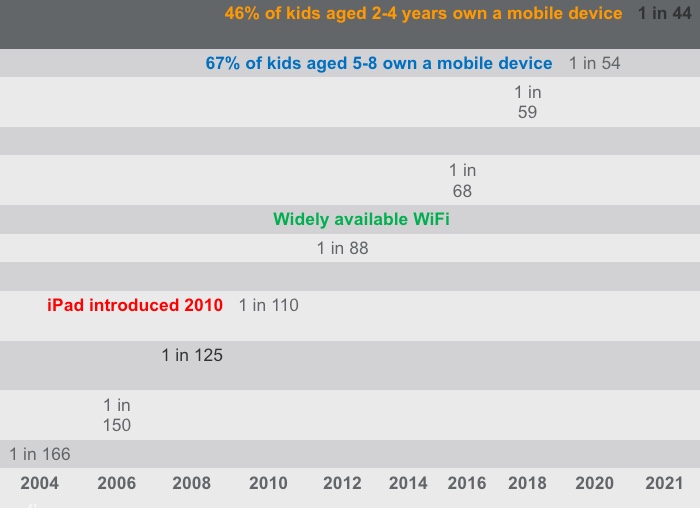

Figure 5. Timeline showing rates of autism over seven years.

Take a look at the timeline illustrating the rates of autism and their increase over time. It's important to note that this is a correlation and not causation, but the pattern is striking. The introduction of the iPad in 2010 coincided with an autism rate of 1 in 110. As we move forward, Wi-Fi became widely available in 2014, and the autism rate rose to 1 in 68 within four years. By 2020, data revealed that 46% of children aged two to four had access to a mobile device, while 67% of children aged five to eight had one. During this period, the autism rate increased to 1 in 54. A year later, it further rose to 1 in 44.

Again, I want to emphasize the importance of conversation and being tuned into the world around you. Here's a great example: Imagine you are a child experiencing a fun car wash where you get out of the car and watch as it goes through the spinning machinery with bubbles all around. I recall an incident where a grandfather had taken his young grandchildren, around six to eight years old, to such a car wash. Instead of enjoying the experience and watching the car go down with all the spinning and bubbles, the grandchildren were engrossed in their devices. The disappointment on the grandfather's face was unforgettable. It was clear how different this was from when he had taken his own children and how exciting and engaging it had been for them.

Impact on Reading

How does screen time impact reading? Consider the importance of perspective-taking in reading. Understanding characters' perspectives requires the ability to think about what others are thinking, and this skill cannot be developed through screens or non-human interactions.

Furthermore, even for older children, think about the concept of deep reading. When you truly immerse yourself in a story or read for meaningful content, executive functions come into play. If these functions are impacted in a way that makes it difficult to ignore distractions, persevere through complex sentence structures, or engage with content that lacks flashy elements, comprehension will be affected.

Now, let's reflect on personal experiences. Have you ever gone through a "book drought," a period when you rely heavily on your phone for news and information but haven't delved into a book for a while? I have experienced this, and I've noticed that although I may have been reading a similar amount of text with similar syntactic complexity, I struggle with the stamina required to read a book. Sustained attention becomes more challenging, especially when processing complex sentences. I find that I need to readjust to the act of reading an actual book, as opposed to consuming fragmented information through platforms like Twitter, Yahoo News, or Facebook posts.

This is significant because the purpose of platforms like Twitter and Facebook is not to promote deep reading. Instead, they foster what's often referred to as "semi-reading." The short and less complex texts on these platforms do not require extensive cognitive effort. Consequently, skim reading has become the norm. Consider your own reading habits. Do you find yourself truly engaging with the text, comprehending deeply, or are you simply scanning for keywords and browsing information?

In addition to perspective-taking and attention, we must also consider the impact on working memory, especially when reading online. With unlimited access to information online, do we store information in the same way? Do we value knowledge in the same way? Let me ask you this: Can you recall your childhood home phone number? I can remember mine. However, how many of us can easily recall our children's or spouse's cell phone numbers? Personally, I rely on my phone to store that information. It appears that I no longer store such details for an extended period of time. We now have instant access to vast factual information, but how do we retain, store, and effectively use all this knowledge?

Reading Outcomes and Other Impacts

How does screen time impact other areas, such as reading outcomes? Let's delve into the concept of brain plasticity. Plasticity refers to the brain's ability to adapt and recover, such as when a person with a head injury improves due to alternative pathways which improve functioning. However, plasticity is contingent on what the brain is asked to do. It responds to the demands placed upon it. Brain plasticity is an incredible aspect of the human body. The brain can adapt and compensate even if someone is born with missing sections (such as lacking a corpus callosum).

Consider the implications of what we demand from our brains when we emphasize speed, information overload, multitasking, and continuous partial attention. What does this do to our brains? One implication is that our attention spans have decreased by approximately half. This poses a challenge for a generation of children who have been trained to have shorter attention spans than what is required for reading a book. If we struggle to sustain attention, we struggle to comprehend the content. Difficulties with memory lead to struggles with the consolidation of information and the development of background knowledge.

A study conducted by the University of Oregon in 2013 (McClelland et al., 2013) revealed an intriguing finding about attention span persistence. Attention span persistence refers to having the persistence to pay attention to something. Attention span persistence not only affects reading and learning but also predicts math and reading scores at the age of 21. Thus, by training an entire generation to have shorter attention spans than what books demand, we fail to train the cognitive patience and perseverance necessary for learning to read. Apps and screens lack the cognitive challenges that encourage persistence. When faced with difficulty, it is easier to swipe right, turn off, or switch to another game.

Another impact is the depth and complexity of what we read. Over the past decade, there have been shifts not only in how and what we read but also in why we read. In terms of quantity, the average person in the US reads about the same number of words as a novel. However, the reading is not continuous, sustained, or concentrated. It is often for entertainment purposes. We read articles here and Facebook posts there, but it mostly serves as a diversion. Our reading tends to be surface-level, lacking deep comprehension. I find it helpful to cut and paste links, email them, and revisit them later for deeper processing and critical analysis. Taking time to reflect on the content ensures that we evaluate potential biases and assess the accuracy of the information.

Visual and Vestibular Systems

Now, let's consider the visual system and the vestibular system in relation to temper tantrums, executive function, and screens. The visual processing system, which involves the intake of visual information, is related to nonverbal scores. Its development begins before the age of two and continues until around age eight or nine. The faster visual information comes in, the quicker the brain must process it to keep up. Excessive screen time causes children to hyper-focus on the screen, straining their brains with rapid processing of constantly changing visual stimuli. Think about the busy screens of apps, filled with quick changes, vivid colors, and flashing lights. Exposing the brain to such stimuli during critical developmental stages can lead to permanent damage, affecting the brain's processing pace.

Consequently, a two-year-old exposed to a constantly fast-paced visual environment of screens may grow up feeling comfortable with that level of stimulation but uncomfortable with the normal pace of everyday life. When the screen is taken away, they may experience difficulty readjusting to real-life speed, resulting in behaviors like screaming, crying, and general chaos as they seek the same level of stimulation that their brain had become accustomed to.

The visual system and the vestibular system are closely interconnected. The vestibular system, responsible for maintaining balance and perceiving one's position in space, also plays a role in influencing mood. For example, consider linear acceleration. Linear acceleration has a calming effect, such as the soothing motion of rocking, swinging, or driving a cranky baby to sleep. In fact, I could almost pinpoint the exact speed at which my kids would fall asleep, even though they are now 19 and 21 years old. I believe it was not just the hum of the car but rather the rate of acceleration that lulled them to sleep. On the other hand, rotational acceleration has an arousing effect. Think of the spinning teacup ride at Disney World. How many of you have experienced feeling queasy after riding those spinning teacups? Our brains are not accustomed to that level of arousal and rotational acceleration, hence the discomfort.

The issue arises when a child's visual system is hyper-focused, intensely engaged, and processing information rapidly, it essentially locks up the vestibular system, and as a result, emotions become imbalanced. The equilibrium is disrupted. Consequently, when children finally step away from the screen, the visual and vestibular systems are unlocked, and they struggle to readjust because they have not been actively engaged or involved during that period. We see a drastic shift in mood, and the impact on emotional regulation becomes evident.

Language

Now, let's discuss the impact of language, specifically the language we expose children to through conversation. Human interaction and physical engagement are crucial. Equally important is children's interaction with books before the age of two, as it plays a critical role in developing their reading circuits. But why is that? When you sit with a child in your lap and share a real book, not an iPad version, something significant happens. On an iPad, interactive elements often distract children. For instance, pushing Curious George might make him climb a tree, or pressing the man with the yellow hat might cause his hat to fly off. Consequently, their attention is drawn to the bells and whistles rather than the story as a whole. Additionally, when you have a child in your lap, reading together allows you to discuss topics beyond their everyday routines.

You can talk about castles, dragons, Africa, astronauts, and outer space because books are not limited to the here and now or even to reality. By doing so, you contribute to their background knowledge, bridging gaps in their understanding. This background knowledge is essential for reading comprehension. In a 1987 study by Recht and Leslie, the impact of background knowledge on seventh and eighth graders was examined. Surprisingly, prior knowledge had a greater impact on reading comprehension than their actual reading ability or decoding skills. Even struggling readers, who had difficulty decoding, outperformed proficient readers when they possessed extensive knowledge about the subject matter. When background knowledge was equalized, comprehension levels were similar, suggesting that the comprehension gap was not due to a lack of skill but rather a knowledge gap.

Sharing books together also exposes children to complex syntax found specifically in stories. For example, consider this sentence you might encounter in a book: "Once upon a time, there was a dark enchanted forest where no light could enter, and no creature could leave. It was in this long, accursed place that a very tiny and very shy toad lived under a very large, most unusual toadstool." Books provide children with the opportunity to hear and become familiar with such intricate sentence structures and narratives.

No one speaks like that in everyday conversation, but that intricate language is part of storytelling. The abundance of prepositional phrases, descriptive adjectives, and captivating vocabulary like "enchanted" and "long accursed" is exclusive to the language of stories found within books. Another crucial element is visual imagery, as we previously discussed. It is an integral part of deep reading, allowing us to create vivid mental movies. Without the ability to construct these visual images, comprehension becomes challenging. Let me provide an example to illustrate this.

Consider the following remarkable story. Ernest Hemingway once engaged in a bet with fellow writers. They challenged him to write a profoundly moving and powerful story using only six words. Despite the constraint, Hemingway managed to evoke a story of immense depth and emotion. Here are the six words he penned: "For sale: baby shoes, never worn." These six words, with the backdrop of your own background knowledge, perspective, and experiences, prompt the formation of visual imagery. You might picture a simple classified ad in a newspaper, or your understanding and personal history may add layers of meaning to the story, enriching the imagery even further.

Play

We have extensively discussed the importance of a language-rich environment where conversations occur, words and concepts are learned, and background knowledge is developed. We have explored how play, songs, chants, and other activities contribute to the sounds of language and social skill development, enhancing our social-emotional and emotional regulation abilities. The overlap between emotional regulation and early executive function skills has also been highlighted, supported by a substantial body of evidence on the impact of language-rich environments on healthy brain development.

The elements listed here—language environment, conversation, vocabulary, phonological awareness, social interaction, social-emotional learning, executive function, and brain development—come from the National Association for the Education of Young Children and the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Play serves as a context for a child's learning. During play, children have the opportunity to practice and reinforce what they have learned across various areas. This learning experience cannot be obtained from worksheets. The American Academy of Pediatrics emphasizes that play is the singular opportunity to promote social-emotional, cognition, language, and self-regulation, all of which build those executive function skills and a social brain that's ready to learn.

Seven Strategies

Now, let's discuss the next steps. I have explained the concerns and why they are significant. Here is a list of key strategies:

- Bring back and facilitate play!

- Provide intentional and deliberate vocabulary instruction.

- Teach emotion vocabulary.

- Connect through conversation.

- Parent training and digital diets.

- Talking tips.

- Reading routines.

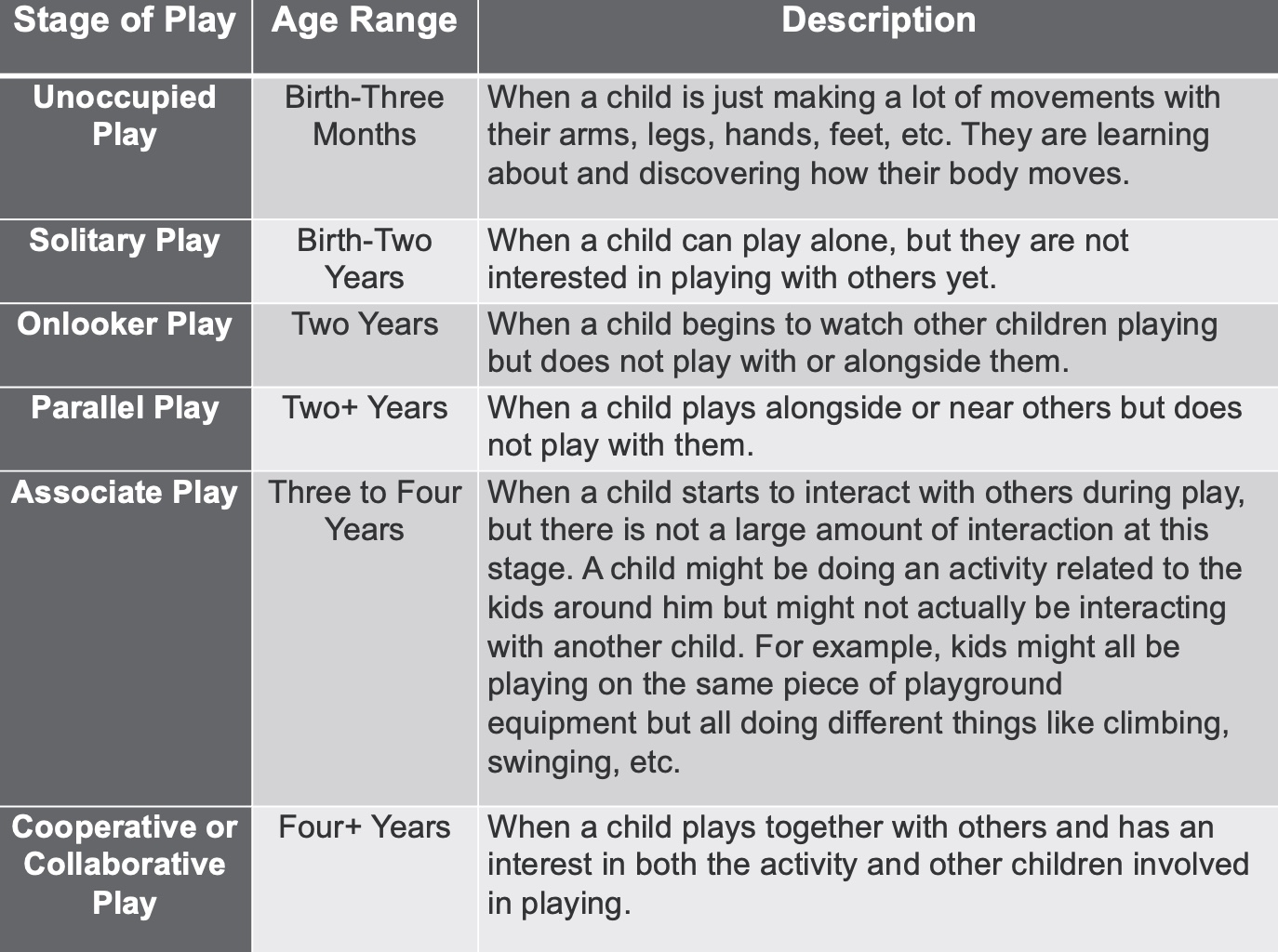

To begin, we must familiarize ourselves with the stages of play. This knowledge will enable us to assess the level of play a child is currently at, whether they are in our classroom or under our guidance. We can then determine how to facilitate their progress to the next stage of play.

Figure 6 illustrates the stages of play along with their descriptions. This will serve as a quick reference, allowing you to recognize the different levels of play. Once you identify the stage a child is in, you can use strategies to facilitate getting them to the next level of play.

Figure 6. Stages of play and descriptions.

Bring Back and Facilitate Play

As an adult facilitating play, you can employ different strategies to enhance language development. Let's explore each approach in more detail.

Self-talk: This is the "I do" component of the "I do, you do, we do" approach. Model self-talk by describing your thoughts and actions. For example, while putting items on the board, you can talk about what needs to be done or share your thought process. This modeling of self-talk helps children understand how to express their own thoughts.

Parallel talk: Engage in parallel talk by describing what the child is doing. For instance, if you observe them playing with a farm set, you can say, "I see you have the pigs, cows, and chickens all together. Should they be in the same area? What do you think?" By initiating this discussion, you encourage their participation and build their language skills.

Recast: Recasting involves repeating what the child said but with slight corrections or expansions. For example, if the child says, "I put him chickens next to the barn," you can respond by asking, "Did he put him chickens or did he put his chickens?" This recast models the correct language without explicitly asking them to say it correctly. Recasting is particularly valuable for improving articulation. If you have a child who is struggling with the "r" sound, and they say, "The barn is wed," you can say, "Is the barn wed, or is it red?"

Expansion: Extend what the child says to encourage more language production. For instance, if the child says, "The cow is by the barn," you can respond with, "Yes, the brown cow is by the barn," or "The brown cow is next to the red barn." By adding more details and expanding their statements, you provide opportunities for them to learn and use additional language. Once you've expanded on their statement, you can then encourage them to repeat the expanded version. For example, you can say, "Okay, now you say it: 'The brown cow is next to the red barn.'" This reinforces their learning and encourages them to use longer and more complex language structures.

Explicit Vocabulary Instruction

Also, we've discussed vocabulary extensively, but how can we effectively teach vocabulary in a meaningful way? We will revisit this topic shortly when we delve into book reading. However, it's important first to understand the necessary steps for teaching it.

1. Pronounce the word and have them repeat it.

2. Write the word on the board/discuss the number of syllables, the number of sounds, unique phonic patterns, morphemes, and/or the word’s origin (depends on age).

3. Talk about what the word means using a student-friendly definition (see below). Add visual supports and experiences with the word to add to background knowledge.

A -------- is (a) -------------------- that (is, does) ---------------.

(word) (synonym, category) (defining attribute)

4. If the word is a noun, talk about visual characteristics (size, shape, color, what it is made of), function, location, and various parts of the named item. This helps to develop visualization skills to support comprehension.

5. Talk about other words that may be connected to that word (synonyms, other words in the same category, contexts the word is typically used, etc.).

6. Give examples of how it can be used and how it cannot be used.

7. Ask questions about the meaning of the word that can be answered with a “yes” or “no” (i.e., Can a valet clean your teeth? Can a valet park your car?).

8. Have students use the new word in various ways and contexts.

9. Frequently use the new word. Adapted from LETRS (Moats & Tolman, 2019).

First, we begin by pronouncing the word and having the students repeat it. For instance, let's take the word "neurasthenic" as an example. You would say it slowly and clearly, emphasizing each syllable: "neu-ras-then-ic." You can even prompt them by saying, "Repeat after me: neurasthenic." By breaking down the word and demonstrating its syllables, you help solidify it in their phonological long-term memory.

Second, depending on the student's age, you may write the word on the board or engage in a discussion while pointing out its syllables, the number of sounds, and the phonetic pattern. For instance, with "neurasthenic," we recognize that it's a medical term of Greek origin. In Greek-related medical terms, the "th" combination produces a "t" sound. This obviously would be something to discuss with older children.

Third, you can explore the word's etymology or origin. Following that, you can explain its meaning by providing a student-friendly definition, essentially using a sentence script. The sentence script takes the form of "A _____ is a _____ that is/does _____." Let's consider the word "kangaroo" as an example. A possible sentence script could be, "A kangaroo is a zoo animal." Or, depending on the goal, you could use, "A kangaroo is a marsupial that carries its baby in its pouch." This sentence frame serves as a foundation. I highly recommend supplementing it with visual support, especially when teaching multilingual learners, as it helps reinforce comprehension. Displaying a picture while introducing the sentence frame can be particularly effective.

For steps four, five, and six, particularly when dealing with nouns, it's essential to discuss their visual characteristics. This includes aspects such as size, shape, color, composition, function, and the location of different parts. This is what fosters the development of visual imagery in relation to comprehension.

Using the example of a kangaroo, you can describe it as a tall animal. To provide a comparison, you might mention that a dog is a short animal, whereas a kangaroo is tall, although not as tall as a giraffe. Kangaroos are typically brown, fuzzy, and furry, and they hop. They are primarily found in Australia. By creating these various visual images, even describing the location of Australia, which students may not be familiar with unless they have been there, you enhance their understanding. Describing the location often has a significant impact on forming visual imagery.

To elaborate further, I would envision a kangaroo in a dirt area, picturing a specific type of reddish clay soil. As the kangaroo hops, I imagine small puffs of red dirt, resembling red dust from the clay, being kicked up. This scaffolding technique aids in clarifying and enhancing visualization. Additionally, you may discuss related words, such as koalas, which are also marsupials that carry their babies in pouches.

Step seven involves sharing synonyms for the word and providing examples of how the word "kangaroo" can and cannot be used. You can pose questions using a yes-or-no format. For example, "Can a kangaroo clean your teeth?" These outrageous questions tend to capture their interest. You can also ask if a kangaroo can hop over a car or some other object, emphasizing that hopping is their natural behavior. This can be illustrated by highlighting how their tail helps with balance. The purpose is to provide examples within a yes-or-no framework.

Finally, steps eight and nine entail having students actively use the newly introduced word. Encourage them to incorporate it into their vocabulary throughout the day. For instance, you might say, "I saw you jumping around during recess like a little kangaroo." By consistently employing the new word, you reinforce its usage and familiarity.

Teaching Emotional Vocabulary

One approach to teaching emotional vocabulary is called the RULER. The RULER approach is essentially this:

R - Recognize how your body feels. Are you tense or relaxed? What is your body posture or energy level? How is your heart rate or breathing?

U - Understand what happened to make you feel this way (context).

L - Label how you feel.

E - Express what you feel in an appropriate way.

R - Regulate your emotion. Do you need to shift your feelings? How do you do that?

First, teach children to recognize their feelings by observing cues from their bodies. For instance, if you see them leaning over, you can say, "I see you leaning over. That must mean you're sad or tired." If they are jumping around, you can say, "I see you're jumping, and you must be really excited about something." It suggests excitement. Pay attention to their breathing patterns as well. If they are breathing heavily and making noise, you may bring attention to that and ask if they are mad. These bodily cues help us understand and label our emotions.

Understanding the context is crucial because emotions are context-driven. For instance, if you see a picture of someone in front of a casket, you don't need to look at their face to know they are likely feeling sadness. The context of being at a funeral and facing a coffin provides clear cues. Therefore, we need to teach children to recognize the context and understand what led to their specific emotions. By identifying the events or situations that triggered uncomfortable feelings, they can gain insight into their emotions.

Encourage children to label their emotions. Although there are approximately 2,000 emotion-related words in the English language, most people only use a small fraction of them. Young children often rely on simple terms like happy, mad, or sad. However, expanding their emotional vocabulary can significantly help them manage their emotions. Differentiating between frustration, anger, anxiety, sadness, and disappointment allows us to respond more effectively and provide appropriate support based on their specific emotions. The more precise we can be in pinpointing and labeling their emotions, the better our support and understanding can be.

Finally, let's address the appropriate expression and regulation of emotions. It's essential to understand when and where it is appropriate to express our emotions. This aspect holds significant importance, and we need to learn how to regulate our emotions and maintain a balanced state. Different strategies can be used, such as taking deep breaths and engaging in positive self-talk. For example, reminding ourselves that we are capable or that our parent will pick us up later, easing any anxiety or worry.

Reframing negative interactions is another helpful technique. We can consider that the other person may also be having a difficult day, which might explain their actions. Creating physical distance, like taking a walk to cool down, is another strategy worth teaching. Seeking support from others is also crucial. Children can learn how to ask for help and communicate with friends.

Cookie Monster on Sesame Street has been addressing emotional regulation long before it became widely discussed. They have exceptional videos that teach self-regulation and emotional management. I highly recommend watching videos like "Name That Emotion" on Sesame Street. They are an excellent resource for helping students identify, understand, recognize, and manage their emotions.

Connect Through Conversation

I have discussed the significance of conversational turn-taking. It is crucial to understand that approximately 20% of children in the classroom are in language isolation. This means that for the majority of their day, these students have fewer than five conversational turns per hour. Even in classrooms where there is a considerable amount of conversation happening, approximately 20% of students are not benefiting from it.

To put this into perspective, it is noteworthy that at home, there are approximately 73% more opportunities for conversational turns compared to school settings.