Question

Why is conversational turn-taking important with young children?

Answer

Why is conversational turn-taking so important? Let me explain the three significant reasons. First and foremost, children need to be exposed to approximately 20,000 words per day or engage in about 40 conversational turns per hour. This is because, as we learned from the Hart and Risley study, conversations and the vocabulary gained from them are the most influential factors in a child's preschool vocabulary. When children have fewer conversations and, consequently, hear fewer familiar or unfamiliar words, they face difficulties when they encounter new words at school. They don't recognize that they haven't heard those words before and lack the knowledge to ask, "What does that word mean?" This lack of vocabulary knowledge affects their listening comprehension and, in turn, impacts their reading comprehension. They may end up skipping over unfamiliar words, further hindering their reading comprehension abilities.

The second reason why conversation is crucial is for phonological long-term memory. Children who engage in more conversations with adults develop the brain architecture necessary for language and are associated with enhanced reading proficiency. Specifically, a significant aspect of language called phonological long-term memory plays a vital role.

To explain it clearly, let me demonstrate. When a young child is reading, they rely on their pronunciation of words and their knowledge of the word's meaning from their oral vocabulary to recognize words in print. When they decode a word like "suspicious," they recognize it because they have heard it before. This is phonological long-term memory—recalling a word from previous encounters. However, if a word is not part of their oral vocabulary, let's say a complex word like "antidisestablishmentarianism," they will struggle to recognize it in print, even if they decode it accurately. Here are examples to illustrate this point.

Grinch

What do you hear in your mind using your phonological long-term memory when you see that word? You have likely stored that word in your phonological long-term memory, and you may be singing the song from the movie How the Grinch Stole Christmas. When you see the word Grinch, you also likely have that image associated with it. I mentioned the importance of visual imagery. You may think about that green fuzzy big bellied guy who's unpleasant, lives in a mountain cave above Whoville, and puts a reindeer antler on top of his dog, Max. It is a very clear visual image. Consequently, the next time you see that word, you will recognize it more quickly and automatically read it. It is not a sight word per se, but it is nearly instantaneous recognition when reading.

Neurasthenic

What do you hear when you see this word? Probably nothing unless you have heard the word before. As a result, you have to decode it chunk by chunk. You have to flex the vowels and play around with the syllable stress. You may rehearse the word with the stress on the various syllables; you don't know which is correct because it is not stored in your phonological long-term memory.

When words are not heard in conversation, they are not learned and not stored in phonological long-term memory for later use in reading.

The final reason that conversation is so important is referred to as the Matthew effect.

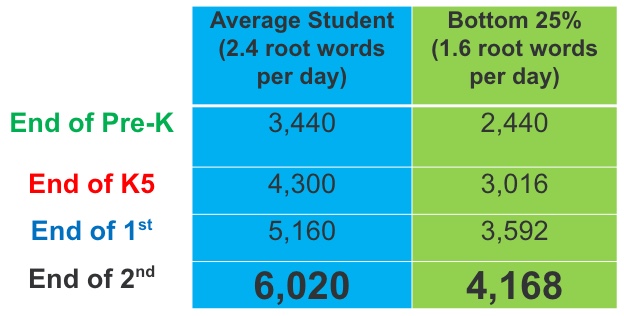

Figure 2. Chart showing The Matthew Effect.

The Matthew Effect

Figure 2 shows that by the end of pre-K, the average student gains about 2.4 root words per day, which amounts to approximately 3,440 new words per year. That's the average child. Now, let's consider a child who started with a vocabulary deficit—those in the bottom 25%. They don't begin with the same number of words and, consequently, don't end up with the same number. In fact, they have about a thousand words less than their peers. This deficit grows to almost 2,000 words by the end of second grade unless we provide explicit instruction. The question is: are we doing that? And if so, how well? Furthermore, what does the data actually say? However, even before pre-K, the research tells us that vocabulary at age three significantly impacts language and reading skills at ages 9 and 10, and it strongly predicts high school graduation.

As someone working in early childhood education, you have the power to make a substantial difference, particularly in terms of vocabulary development. I'm not sure what assessment tool you use for entry into kindergarten, but in our state, we use the kindergarten readiness assessment, which is why that data is crucial. Often, the data from this assessment doesn't provide us with information to influence our instruction directly. However, the kindergarten readiness assessment data aims to help us understand what happened before children entered school and identify any trends. This is crucial because, once again, children who start behind tend to stay behind unless we change our approach.

The last point I want to emphasize is regarding vocabulary, and it draws from the Hart and Risley study. While their research initially focused on low socioeconomic status (SES) children, the importance of a language-rich environment is now applicable across all socioeconomic backgrounds. In other words, even children from middle or upper-class households may not engage in language-rich conversations if they or their parents are preoccupied with technology devices. Consequently, when words go unheard, concepts go unlearned.

This Ask the Expert is an edited excerpt from the course The Impact of Tech on Development and Academic Readiness, presented by Angie Neal, MS, CCC-SLP.